Ajuran Sultanate

Ajuuraan Sultanate Dawladdii Ajuuraan ( Arabic ) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century–18th century | |||||||||||||

|

The banner of Mogadishu | |||||||||||||

Oromo invasions | Mid-17th century | ||||||||||||

• Decline | 18th century | ||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Somalia Ethiopia | ||||||||||||

The Ajuran Sultanate (

Trading routes dating from ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were strengthened and re-established, foreign trade and commerce in the coastal provinces flourished with ships sailing to and from kingdoms and empires in the Near East, East Asia, and the wider world.[13][14]

Etymology

The Ajuran Empire traces its name back to the Arabic word; إيجار (Ījārā), which means to rent or tax. A name well deserved for the exorbitant tributes paid to the Empire.[15]

Location

Historically, the Sultanate of Mogadishu was confined by the Adal Sultanate in the north.[17][18] Throughout the Middle Ages, the Ajurans routinely aligned themselves politically with the Adalites.[19][20] Described as one country by Ibn Battuta, a journey to Mogadishu from the town of Zeila took him eight weeks to complete.[21][22]

The Ajuran Empire's sphere of influence in the Horn of Africa was among the largest in the region. At the height of its reach, the empire covered most of southern Somalia as well as eastern Ethiopia,[13][23] with its domain at one point extending from Hafun in the north to Kismayo in the south, and Qelafo in the west.[24][25][26]

Origins and the House of Garen

| The House of Gareen Known members |

|---|

|

The House of Garen was the ruling hereditary dynasty of the Ajuran Empire.[27][28] Its origin lies in the Garen Kingdom that during the 13th century ruled parts of the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[29] With the migration of Somalis from the northern half of the Horn region southwards, new cultural and religious orders were introduced, influencing the administrative structure of the dynasty.[30] A system of governance began to evolve into an Islamic government. Through their genealogical Baraka, which came from the saint Balad (who was known to have come from outside the Kingdom).[31][32][33]

Administration

The Ajuran nobility used many of the typical Somali aristocratic and court titles, with the Garen rulers styled Imam.[34] These leaders were the empire's highest authority, and counted multiple Sultans, Emirs, and Kings as clients or vassals. The Garen rulers also had seasonal palaces in Mareeg, Qelafo and Merca, important cities in the Empire were Mogadishu and Barawa. The state religion was Islam, and thus law was based on Sharia.[35][36][37]

- Imam – Head of State[38]

- Emir – Commander of the armed forces and navy

- Na'ibs – Viceroys[39]

- Wazirs – Tax and revenue collectors

- Qadis – Chief Judges

Citizenry

Through their control of the region's wells, the Garen rulers effectively held a monopoly over their

With the centralized supervision of the Ajuran, farms in

Taxation

The State collected

A political device that was implemented by the Garen rulers in their realm was a form of

For trade, the Ajuran Empire minted its own Ajuran currency.[45] It also utilized the Mogadishan currency originally minted by the Sultanate of Mogadishu, which later became incorporated into the Ajuran Empire.[46] Mogadishan coins have been found as far away as the present-day country of the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East.[47]

Urban and maritime centers

The urban centers of

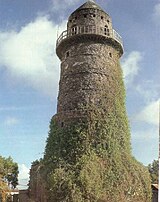

Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century[53] noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[54][55] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory.[56][57] Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[58][59]

Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[60] together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[61] There were Jewish merchants from the Hormuz who brought their Indian textile and fruits to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[62][63]

Trading relations were established with

Economy

The Ajuran Empire relied on agriculture and trade for most of its income. Major agricultural towns were located on the

The Ajuran Empire also minted its own

Through the use of commercial vessels, compasses, multiple port cities, light houses and other technology, the merchants of the Ajuran Empire did brisk business with traders from the following states:

| Trading countries in Asia | Imports | Exports |

|---|---|---|

Ming Empire |

celadon wares and their currency | horses, exotic animals, and ivory |

| Mughal Empire | spices |

gold, wax and wood |

| Malacca Sultanate | ambergris and porcelain | cloth and gold

|

| Maldive Islands | cowries |

musk and sheep |

Kingdom of Jaffna |

cinnamon and their currency | cloth

|

| Trading countries in the Near East | ||

| Ottoman Empire | cannons |

textiles

|

Safavid Persian Empire |

textiles and fruit |

grain and wood |

| Trading countries in Europe | ||

| Portuguese Empire | gold | cloth

|

Venetian Empire |

sequins | – |

Dutch Empire |

– | – |

| Trading countries in Africa | ||

Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) |

– | cloth

|

| Adal Sultanate | – | – |

| Ethiopian Empire | – | – |

Swahili Coast |

– | – |

| Monomopata | gold and ivory | cloth

|

| Gonderine Ethiopian Empire | gold and cattle | cloth

|

| Merina Kingdom | – | – |

Diplomacy

With their maritime pursuits, the Ajuran Empire established trading and diplomatic ties across the old world, especially in Asia, from being close allies of the grand power of the

The ruler of the Ajuran Empire sent ambassadors to

Major cities

The Ajuran Empire was an influential Somali kingdom that held sway over several cities and towns in central and southern Somalia during the Middle Ages. A few of the cities and towns were abandoned or destroyed:

- Capital

- Mareeg (initially) (town in the Galguduud region of Somalia)

- Qelafo (town in the Somali Region of Ethiopia)

- Lower Shebelleregion of Somalia)

- Mogadishu (harbor city and current capital of Somalia)

- Port cities

- Hobyo (harbor city in the Mudug region of Somalia)

- Eyl (port town in the Nugal region of Somalia)

- Hafun (port town in the Bari region of Somalia)

- Galgaduudregion of Somalia)

- Kismayo (port city in the Lower Juba region of Somalia)

- Lower Shebelleregion of Somalia)

- Middle Shebelleregion of Somalia)

- Other cities

- Lower Shebelleregion of Somalia)

- Baidoa (a city in the Bay region of Somalia)

- Gondershe (abandoned, but now a popular tourist attraction site)

- Hannassa (abandoned)

- Ras Bar Balla (abandoned)

Culture

The Ajurans developed a very rich culture combining various forms of

The traditional martial art

Artistic carving was considered the craft of men similar to how the Somali textile industry was mainly a women's business. Amongst the

In the Merca area, various pillar tombs still exist, which local tradition holds were built in the 16th century, when the Ajuran Empire's naa'ibs governed the district.[91][92]

Muslim migrations

The late 15th and 17th centuries saw the arrival of Muslim families from

Bale

The most famous Somali scholar of Islam from the Ajuraan period is Sheikh Hussein, who was born in Merca, one of the power jurisdiction and cultural centers of the Ajuran Empire.[96] He is credited with converting the Sidamo people living in the area of what is now the Bale Province, Ethiopia to Islam.[97] He is also credited with establishing the Sultanate of Bale. Despite the Bale Sultanate not being directly under Ajuran rule, the two kingdoms were deeply connected and Bale was heavily influenced by Ajuran.[98][99]

His tomb lies in the town of Sheikh Hussein in what is considered the most sacred place in the country for Ethiopian Muslims, in particular those of Oromo ethnic descent.[100][101]

Military

The Ajuran State had a standing army with which the governors ruled and protected their subjects. The bulk of the army consisted of recruited soldiers who did not have any loyalties to the traditional Somali clan system, thereby making them more reliable.

In the early period, the army's weapons consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as

The Ottomans would also remain a key ally during the Ajuran-Portuguese wars. Horses used for military purposes were raised in the interior, and numerous stone fortifications were erected to provide shelter for the army in the coastal districts.[109] In each province, the soldiers were under the supervision of a military commander known as an emir.[103] The coastal areas and the lucrative Indian Ocean trade were protected by a navy.[110]

Ajuran-Portuguese battles

The European Age of Discovery brought Europe's then superpower the Portuguese Empire to the coast of East Africa, which enjoyed a flourishing trade with foreign nations. The southeastern city-states of Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi, Pate and Lamu were all systematically sacked and plundered by the Portuguese.[112] Tristão da Cunha then set his eyes on Ajuran territory, where the Battle of Barawa was fought.[113] After a long period of engagement, the Portuguese soldiers burned the city and looted it.[114] Fierce resistance by the local populace and soldiers resulted in the failure of the Portuguese to permanently occupy the city, and the inhabitants who had fled to the interior eventually returned and rebuilt the city.[115][116][117]

After Barawa, Tristão set sail for Mogadishu, the richest city on the East African coast.[118][119] Word had spread of what had happened in Barawa, and a large troop mobilization took place. Many horsemen, soldiers and battleships in defense positions were guarding the city. Nevertheless, Tristão opted to storm and attempt to conquer the city, although every officer and soldier in his army opposed this, fearing certain defeat if they were to engage their opponents in battle. Tristão heeded their advice and sailed for Socotra instead.[120][121]

Over the next decades tensions remained high and the increased contact between Somali

The Somali-Ottoman offensive managed to drive out the Portuguese from several important cities such as Pate, Mombasa and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor sent envoys to Portuguese India requesting a large Portuguese fleet. This request was answered and it reversed the previous offensive of the Muslims into one of defense. The Portuguese armada managed to re-take most of the lost cities and began punishing their leaders, but they refrained from attacking Mogadishu, securing the city's autonomy in the Indian Ocean.[46][125] The Ottoman Empire would remain an economic partner.[13] Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries the Ajurans successively defied Portuguese hegemony on the Indian Ocean by employing a new coinage which followed the Ottoman pattern, thus proclaiming an attitude of economic independence in regard to the Portuguese.[126][127][128][129]

Gaal Madow

In the mid-17th century, the Oromo people collectively began expanding from their homeland towards the southern Somali coast at a time when the Ajurans were at the height of their power.[130] The Garen rulers conducted several military expeditions known as the Gaal Madow Wars on the Oromo invaders, converting those that were captured to Islam.[131][132][133][134]

Decline

The Ajuran Empire slowly declined in power at the end of the 17th century. The most prominent of setbacks were the dethronement of the

Taxation and the practice of primae noctis were the main catalysts for the revolts against Ajuran rulers.[138] The loss of port cities and fertile farms meant that much needed sources of revenue were lost to the rebels.[139]

Somali maritime enterprise significantly declined after the collapse of the Ajuran Empire. However, other polities such as the Warsangali Sultanate,

Legacy

The empire left an extensive

In the fifteenth century, for example, the Ajuran Empire was the only

See also

| History of Somalia |

|---|

|

|

|

References

- ^ Caulfield, J. Benjamin (1850). Mathematical & physical geography. Edwards & Hughes, 12, Ave Maria Lane. p. 190.

- ^ Reid, Hugo (1853). A System of Modern Geography ... with Exercises of Examination. To which are Added Treatises on Astronomy and Physical Geography. p. 166.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-37857-7.

- ^ "Ajuran | historical state, Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (1989). "The Emergence and Role of Political Parties in the Inter-River Region of Somalia from 1947–1960". Ufahamu. 17 (2): 98.

- ISBN 978-1-874209-98-0.

- ^ Luc Cambrézy, Populations réfugiées: de l'exil au retour, p.316

- ISBN 978-1-387-98657-6.

- ISSN 1469-5138.

- ISBN 978-3-7562-5152-0.

- ISBN 978-0-429-42695-7

- ^ Furlow, Richard Bennett (2013). The spectre of colony: colonialism, Islamism, and state in Somalia (Report). Arizona State University. p. 7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61069-106-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-085458-4

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- ^ Linschoten, Jan Huyghen van (1644). Beschrijvinge vande gantsche custe van Guinea, Manicongo, Angola, Monomotapa, ende tegenover de Cabo de S. Augustijn in Brasilien ... midtsgaders de voorder beschrijvinge op de caerten van Madagascar, ander 't eylant S. Laurens ghenoemt ... noch volght de beschrijvinge van West-Indien int langh, met hare caerte (in Dutch).

- ISBN 9780521209816.

- ^ Landmann, George (1835). A universal gazetteer; or, Geographical dictionary of the world. Longman and Company [and others].

- ISBN 978-1-4766-0889-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-52309-7.

- ^ Burton, Richard (April 2011). First Footsteps in East Africa. B & R Samizdat Express.

…I came to the city of Zeila. This is a settlement of the "Berbers", a people of Sudan, of the Shafia sect. Their country is of two months extent: the first part is termed Zeila, the last Makdishu.

- ^ Northeast African Studies. Vol. 11. African Studies Center, Michigan State University. 1989. p. 115.

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 102.

- ^ Delahaye, Guillaume-Nicolas (1753). Nouvelle Mappe Monde: dediée auf progres de nos connoissances (in French). R. J. Julien.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ISBN 978-0-8133-7402-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-52309-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-52309-7.

- ^ Mondes en développement (in French). Éditions techniques et économiques. 1989. p. 87.

- ^ Cassanelli, Lee V. (1973). The Benaadir Past: Essays in Southern Somali History. University of Wisconsin--Madison. pp. 34–44.

- ISBN 978-1-315-31139-5.

- ^ Nelson, Harold D. (1982). Somalia, a Country Study. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 11.

…led by the Arab influenced Hawiye, a Samaale clan-family that had entered the region from the Ogaden

- ISBN 978-986-06246-3-2.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ^ Abdullahi, Abdurahman (2021). "The Conception of Islam in Somalia: Consensus and Controversy". Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies. 1.

- ISBN 978-0-7556-3515-3.

- ISBN 978-1-909112-79-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- ISBN 978-1-961362-05-5.

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 149.

- ISBN 978-0-429-49928-9

- ^ The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600-1900 - Page 95

- ISBN 978-1-961362-05-5.

- ^ a b Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 206. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- ^ Chittick, H. Neville (1976). An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975. British Institute in Eastern Africa. pp. 117–133.

- ISBN 978-81-206-0867-2.

- ISBN 978-1-61775-697-9.

- ISBN 978-0-486-13194-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4772-2903-3.

- ^ Hegde, Dr P. D. (9 September 2021). A brief History of Great Inventions. K.K. Publications. p. 211.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- ^ Towle, George Makepeace (1878). The Voyages and Adventures of Vasco Da Gama. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Company. p. 257.

- ISBN 978-1-108-01296-6.

- ISBN 978-91-506-1123-6.

- ISBN 978-1-003-81615-7.

- ^ East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- JSTOR 217389.

- JSTOR 217389.

- ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- ISBN 978-1-317-45835-7.

- ISBN 978-1-003-81615-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4

- ^ Chinese Porcelain Marks from Coastal Sites in Kenya: aspects of trade in the Indian Ocean, XIV-XIX centuries. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1978 pg 2

- ^ East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- ^ Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.45

- ISBN 978-1-7936-1233-5.

- ISSN 2468-4791.

- ISBN 978-1-4985-7615-4.

- ISBN 978-3-030-21994-9

- ISBN 978-1-63388-771-8.

- ISSN 1474-0591.

- ^ Wilson, Samuel M. (December 1992). "The Emperor's Giraffe". Natural History. 101 (13). Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian.

- ^ "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Zheng He'S Voyages to the Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-605-70819-3-3.

- ^ A short system of polite learning: being a concise introduction to the arts and sciences, and other branches of useful knowledge. Adapted for schools. W. Bent. 1789. p. 62.

- ^ Ogilby, John (1670). Africa: Being Accurate Description of the Regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billendulgerid, the Land of Negroes, Guinee, AEthiopia, and the Abyssines; with All the Adjacent Island. T. Johnson. p. 488.

- ISBN 978-1-85065-898-6.

- ISBN 978-90-04-16729-2.

- ^ Reese, Scott Steven (1996). Patricians of the Benaadir: Islamic Learning, Commerce and Somali Urban Identity in the Nineteenth Century. University of Pennsylvania. p. 176.

- ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- ISBN 978-0-231-70023-8.

- ISBN 978-1-5275-0685-5.

- ISSN 2407-7542.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- ^ "Fakhr al-Din Mosque". Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2013. ArchNet – Masjid Fakhr al-Din

- ^ Culture and customs of Somalia By Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi pg 97

- ^ a b Cassanelli (1982), p. 101

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 97.

- ISBN 978-90-04-16729-2.

- ISBN 978-1-5069-0410-8.

- JSTOR 217250.

- JSTOR 1791718.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-2025-5.

- S2CID 162230535.

- ISBN 978-0-89130-658-0.

- ISBN 978-3-8258-5671-7.

- ISSN 1474-0699.

- ISBN 978-1-000-99280-9.

- ^ a b Cassanelli (1982), p. 90.

- ^ Macpherson, David (1812). The History of the European Commerce with India: To which is Subjoined a Review of the Arguments for and Against the Trade with India ... Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. p. 16.

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 104.

- ISBN 978-0-8426-1588-4.

- ^ Soucek, 2008, p.48.

- ISBN 978-605-70819-3-3.

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 92.

- ^ a b Welch (1950), p. 25.

- ^ Maritime Discovery: A History of Nautical Exploration from the Earliest Times pg 198

- ISSN 0306-8374.

- ISBN 978-90-04-34632-1

- ^ Guidance, Somalia Ministry of Information and National (1975). Somalia Today: Facts and General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic.

- ISBN 978-605-70819-3-3.

- ^ Njoku (2013), p. 14.

- ^ The book of Duarte Barbosa – Page 30

- ISBN 978-9966-25-460-3.

- ISBN 978-1-000-99280-9.

- ^ The History of the Portuguese, During the Reign of Emmanuel pg.287

- ISBN 978-1-78578-184-1.

- ^ Tanzania notes and records: the journal of the Tanzania Society pg 76

- ^ Schurhammer, Georg (1977). Francis Xavier: His Life, his times - vol. 2: India, 1541-1545.

- ^ "Letter from João de Sepúlveda to the King, Mozambique, 1542 August 10", in Documents on the Portuguese in Mozambique and Central Africa 1497-1840 Vol. III (1540-1560). National Archives of Rhodesia, Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos. Lisbon, 1971 p.133

- ^ Four centuries of Swahili verse: a literary history and anthology – p. 11

- ^ COINS FROM MOGADISHU, c. 1300 to c. 1700 by G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 36

- ^ King, Joe (1 December 1986). Süleyman the Magnificent. Marine Publishing.

- ISBN 978-0-253-02732-0.

- ISBN 978-1-000-85590-6.

- ^ Cassanelli (1982), p. 114.

- ^ Cerulli, Somalia 1: 65–67

- ISBN 978-1-874209-98-0.

- ISBN 978-0-85255-280-3.

- ISBN 979-8-88731-671-0.

- ^ Lewis (1988), p. 37.

- ISSN 1469-5138.

- ^ Mohamed Hassan, Abdikariim Sheikh (2020). "Assessing the Effect of Microfinance Institutions' Services on Financial Perfromance of Small Scale Enterprises in Somalia: A Case of Mogadishu City". International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE). 7: 41.

- ISBN 978-1-63388-771-8.

- ISSN 1469-5138.

- ISBN 978-1-5026-2607-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7.

- ^ Cassanelli, Lee V. (1973). The Benaadir Past: Essays in Southern Somali History. University of Wisconsin--Madison.

- ISBN 978-1-961362-05-5.

- ^ Human-Earth System Dynamics Implications to Civilizations By Rongxing Guo Page 83

- ^ Firmin, Toleve K. (14 May 2020). The Untold Story Of Slavery. Djovi Yom Joel Hounakey.

- ^ Njoku (2013), p. 41.

Sources cited

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- Cassanelli, Lee V. (1982). The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600–1900. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-7832-3.