Ciliate

| Ciliate Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

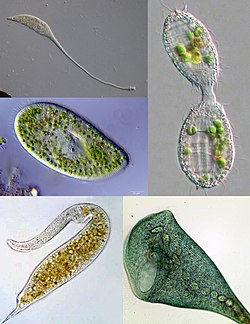

| Some examples of ciliate diversity. Clockwise from top left: Lacrymaria, Coleps, Stentor, Dileptus, Paramecium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | TSAR

|

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora Doflein , 1901 emend.

|

| Subphyla and classes[1] | |

See text for subclasses. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The ciliates are a group of

Ciliates are an important group of

In most systems of

Cell structure

Nuclei

Unlike most other

Division of the macronucleus occurs in most ciliate species, apart from those in class Karyorelictea, whose macronuclei are replaced every time the cell divides.[17] Macronuclear division is accomplished by amitosis, and the segregation of the chromosomes occurs by a process whose mechanism is unknown.[15] After a certain number of generations (200–350, in Paramecium aurelia, and as many as 1,500 in Tetrahymena[17]) the cell shows signs of aging, and the macronuclei must be regenerated from the micronuclei. Usually, this occurs following conjugation, after which a new macronucleus is generated from the post-conjugal micronucleus.[15]

Cytoplasm

Specialized structures in ciliates

Mostly, body cilia are arranged in mono- and

The infraciliature is one of the main components of the cell cortex. Others are the alveoli, small vesicles under the cell membrane that are packed against it to form a pellicle maintaining the cell's shape, which varies from flexible and contractile to rigid. Numerous mitochondria and extrusomes are also generally present. The presence of alveoli, the structure of the cilia, the form of mitosis and various other details indicate a close relationship between the ciliates, Apicomplexa, and dinoflagellates. These superficially dissimilar groups make up the alveolates.

Feeding

Most ciliates are

Many species are also mixotrophic, combining phagotrophy and phototrophy through kleptoplasty or symbiosis with photosynthetic microbes.[18][19]

The ciliate Halteria has been observed to feed on chloroviruses.[20]

Feeding techniques vary considerably, however. Some ciliates are mouthless and feed by absorption (osmotrophy), while others are predatory and feed on other protozoa and in particular on other ciliates. Some ciliates parasitize animals, although only one species, Balantidium coli, is known to cause disease in humans.[21]

Reproduction and sexual phenomena

Reproduction

Ciliates reproduce asexually, by various kinds of fission.[17] During fission, the micronucleus undergoes mitosis and the macronucleus elongates and undergoes amitosis (except among the Karyorelictean ciliates, whose macronuclei do not divide). The cell then divides in two, and each new cell obtains a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.

Typically, the cell is divided transversally, with the

Fission may occur spontaneously, as part of the vegetative

Conjugation

- Overview

Ciliate conjugation is a sexual phenomenon that results in

In many ciliates, such as Paramecium, conjugating partners (gamonts) are similar or indistinguishable in size and shape. This is referred to as "isogamontic" conjugation. In some groups, partners are different in size and shape. This is referred to as "anisogamontic" conjugation. In sessile peritrichs, for instance, one sexual partner (the microconjugant) is small and mobile, while the other (macroconjugant) is large and sessile.[24]

In Paramecium caudatum, the stages of conjugation are as follows (see diagram at right):

- Compatible mating strains meet and partly fuse

- The micronuclei undergo meiosis, producing four haploid micronuclei per cell.

- Three of these micronuclei disintegrate. The fourth undergoes mitosis.

- The two cells exchange a micronucleus.

- The cells then separate.

- The micronuclei in each cell fuse, forming a diploid micronucleus.

- Mitosis occurs three times, giving rise to eight micronuclei.

- Four of the new micronuclei transform into macronuclei, and the old macronucleus disintegrates.

- Binary fission occurs twice, yielding four identical daughter cells.

DNA rearrangements (gene scrambling)

Ciliates contain two types of nuclei:

The macronucleus begins as a copy of the micronucleus. The micronuclear chromosomes are fragmented into many smaller pieces and amplified to give many copies. The resulting macronuclear chromosomes often contain only a single gene. In Tetrahymena, the micronucleus has 10 chromosomes (five per haploid genome), while the macronucleus has over 20,000 chromosomes.[27]

In addition, the micronuclear genes are interrupted by numerous "internal eliminated sequences" (IESs). During development of the macronucleus, IESs are deleted and the remaining gene segments, macronuclear destined sequences (MDSs), are spliced together to give the operational gene. Tetrahymena has about 6,000 IESs and about 15% of micronuclear DNA is eliminated during this process. The process is guided by

In

Aging

ln clonal populations of Paramecium, aging occurs over successive generations leading to a gradual loss of vitality, unless the cell line is revitalized by conjugation or

Fossil record

Until recently, the oldest ciliate fossils known were

Phylogeny

According to the 2016 phylogenetic analysis,

The odontostomatids were identified in 2018[34] as its own class Odontostomatea, related to Armophorea

| Ciliophora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

Several different classification schemes have been proposed for the ciliates. The following scheme is based on a molecular

- Class Mesodiniea (e.g. Mesodinium)

Subphylum Postciliodesmatophora

- Class Stentor)

- Class Karyorelictea

Subphylum Intramacronucleata

- Class Armophorea

- Class Odontostomatea[34] (e.g. Discomorphella, Saprodinium)

- Class Cariacothrix caudata)

- Class Muranotrichea

- Class Parablepharismea

- Class Colpodea (e.g. Colpoda)

- Class Litostomatea

- Subclass Haptoria (e.g. Didinium)

- Subclass Rhynchostomatia

- Subclass Trichostomatia (e.g. Balantidium)

- Class Nassophorea

- Class Phyllopharyngea

- Subclass Chonotrichia

- Subclass Cyrtophoria

- Subclass Rhynchodia

- Subclass Suctoria (e.g. Podophyra)

- Subclass Synhymenia

- Subclass

- Class Oligohymenophorea

- Subclass Apostomatia

- Subclass Astomatia

- Subclass Hymenostomatia (e.g. Tetrahymena)

- Subclass Peniculia (e.g. Paramecium)

- Subclass Peritrichia (e.g. Vorticella)

- Subclass Scuticociliatia

- Subclass

- Class Plagiopylea

- Class Prostomatea (e.g. Coleps)

- Class Protocruziea

- Class Spirotrichea

- Subclass Choreotrichia

- Subclass Euplotia

- Subclass Hypotrichia

- Subclass Licnophoria

- Subclass Oligotrichia

- Subclass Phacodiniidea

- Subclass Protohypotrichia

- Subclass

Other

Some old classifications included

Pathogenicity

The only member of the ciliate phylum known to be pathogenic to humans is Balantidium coli,[36] which causes the disease balantidiasis. It is not pathogenic to the domestic pig, the primary reservoir of this pathogen.[37]

References

- ^ PMID 27126745.

- S2CID 247677842.

- ISBN 9789048128006.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-4020-8238-2.

- ^ "ITIS Report". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- PMID 28875267.

- PMID 19121402.

- S2CID 25977768.

- ^ Alfred Kahl (1930). Urtiere oder Protozoa I: Wimpertiere oder Ciliata -- Volume I General Section And Prostomata.

- ^ "Medical Definition of CILIATA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- PMID 30257078.

- PMID 16248873.

- ISBN 9781483186146.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-28147-6.

- PMID 8078435.

- ^ )

- PMID 20970377.

- PMID 32917704.

- PMID 36574690.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-8238-2.

1007/978-1-4020-8239-9

- ^ )

- PMID 3743667.

- ^ a b c Raikov, I.B (1972). "Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 4: 149.

- ^ Finley, Harold E. "The conjugation of Vorticella microstoma." Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1943): 97-121.

- ^ "Introduction to the Ciliata". Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ PMID 21956937.

- S2CID 28320562.

- PMID 424739.

- S2CID 11992591.

- PMID 8127914.

- ^

Li, C.-W.; et al. (2007). "Ciliated protozoans from the Precambrian Doushantuo Formation, Wengan, South China". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 286 (1): 151–156. S2CID 129584945.

- PMID 23213234.

- ^ S2CID 5032558

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (2000). Flagellate megaevolution: the basis for eukaryote diversification. In: Leadbeater, B.S.C., Green, J.C. (eds.). The Flagellates. Unity, diversity and evolution. London: Taylor and Francis, pp. 361-390, p. 362, [1].

- ^ "Balantidiasis". DPDx — Laboratory Identification of Parasitic Diseases of Public Health Concern. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013.

- PMID 18854484.

Further reading

- Lynn, Denis H. (2008). The ciliated protozoa: characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. OCLC 272311632.

- Hausmann, Klaus; Bradbury, Phyllis C., eds. (1996). Ciliates: cells as organisms. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. OCLC 34782787.

- Lee, John J.; Leedale, Gordon F.; Bradbury, Phyllis C., eds. (2000). An illustrated guide to the protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups (2nd ed.). Lawrence, KS: Society of Protozoologists. OCLC 49191284.

External links

Media related to Ciliophora at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ciliophora at Wikimedia Commons