Jaguar

| Jaguar Temporal range:

Middle Pleistocene – present (~500,000–0 YBP)[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. onca

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera onca | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Current range

Former range | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is a large

The modern jaguar's ancestors probably entered the Americas from

The jaguar is threatened by

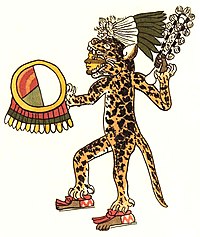

The jaguar has featured prominently in the mythology of

Etymology

The word "jaguar" is possibly derived from the

Taxonomy and evolution

Taxonomy

In 1758,

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several jaguar

By 2005, nine subspecies were considered to be valid taxa:[3]

- P. o. onca (Linnaeus, 1758) was a jaguar from Brazil.[11]

- P. o. peruviana (De Blainville, 1843) was a jaguar skull from Peru.[13]

- P. o. hernandesii (Gray, 1857) was a jaguar from Mazatlán in Mexico.[14]

- P. o. palustris (Ameghino, 1888) was a fossil jaguar mandible excavated in the Sierras Pampeanas of Córdova District, Argentina.[15]

- P. o. centralis (Mearns, 1901) was a skull of a male jaguar from Talamanca, Costa Rica.[16]

- P. o. goldmani (Mearns, 1901) was a jaguar skin from Yohatlan in Campeche, Mexico.[16]

- P. o. paraguensis (Hollister, 1914) was a skull of a male jaguar from Paraguay.[17]

- P. o. arizonensis (Goldman, 1932) was a skin and skull of a male jaguar from the vicinity of Cibecue, Arizona.[18]

- P. o. veraecrucis (Nelson and Goldman, 1933) was a skull of a male jaguar from San Andrés Tuxtla in Mexico.[19]

Reginald Innes Pocock placed the jaguar in the

Evolution

The Panthera

The lineage of the jaguar appears to have originated in Africa and spread to Eurasia 1.95–1.77 mya. The modern species may have descended from Panthera gombaszoegensis, which is thought to have entered the American continent via Beringia, the land bridge that once spanned the Bering Strait,[29][30] though other authors have disputed the close relationship between P. gombaszoegensis (which is primarily known from Europe) and the modern jaguar.[31] Fossils of modern jaguars have been found in North America dating to over 850,000 years ago.[5] Results of mitochondrial DNA analysis of 37 jaguars indicate that current populations evolved between 510,000 and 280,000 years ago in northern South America and subsequently recolonized North and Central America after the extinction of jaguars there during the Late Pleistocene.[20]

Two extinct subspecies of jaguar are recognized in the fossil record: the North American P. o. augusta and South American P. o. mesembrina.[32]

Description

The jaguar is a compact and muscular animal. It is the largest cat native to the Americas and the third largest in the world, exceeded in size only by the tiger and the lion.[5][33][34] It stands 57 to 81 cm (22.4 to 31.9 in) tall at the shoulders.[35][36] Its size and weight vary considerably depending on sex and region: weights in most regions are normally in the range of 56–96 kg (123–212 lb). Exceptionally big males have been recorded to weigh as much as 158 kg (348 lb).[37][38] The smallest females from

Size tends to increase from north to south. Jaguars in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Pacific coast of central Mexico weighed around 50 kg (110 lb).[40] Jaguars in Venezuela and Brazil are much larger, with average weights of about 95 kg (209 lb) in males and of about 56–78 kg (123–172 lb) in females.[5]

The jaguar's coat ranges from pale yellow to tan or reddish-yellow, with a whitish underside and covered in black spots. The spots and their shapes vary: on the sides, they become rosettes which may include one or several dots. The spots on the head and neck are generally solid, as are those on the tail where they may merge to form bands near the end and create a black tip. They are elongated on the middle of the back, often connecting to create a median stripe, and blotchy on the belly.[5] These patterns serve as camouflage in areas with dense vegetation and patchy shadows.[41] Jaguars living in forests are often darker and considerably smaller than those living in open areas, possibly due to the smaller numbers of large, herbivorous prey in forest areas.[42]

The jaguar closely resembles the leopard but is generally more robust, with stockier limbs and a more square head. The rosettes on a jaguar's coat are larger, darker, fewer in number and have thicker lines, with a small spot in the middle.[39] It has powerful jaws with the third-highest bite force of all felids, after the tiger and the lion.[43] It has an average bite force at the canine tip of 887.0 Newton and a bite force quotient at the canine tip of 118.6.[44] A 100 kg (220 lb) jaguar can bite with a force of 4.939 kN (1,110 lbf) with the canine teeth and 6.922 kN (1,556 lbf) at the carnassial notch.[45]

Color variation

In 2004, a camera trap in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains photographed the first documented black jaguar in Northern Mexico.[49] Black jaguars were also photographed in Costa Rica's Alberto Manuel Brenes Biological Reserve, in the mountains of the Cordillera de Talamanca, in Barbilla National Park and in eastern Panama.[50][48][51][52]

Distribution and habitat

In 1999, the jaguar's historic range at the turn of the 20th century was estimated at 19,000,000 km2 (7,300,000 sq mi), stretching from the southern United States through Central America to southern Argentina. By the turn of the 21st century, its global range had decreased to about 8,750,000 km2 (3,380,000 sq mi), with most declines in the southern United States, northern Mexico, northern Brazil, and southern Argentina.[53] Its present range extends from Mexico through Central America to South America comprising

Jaguars have been occasionally sighted in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.[54][55] Between 2012 and 2015, a male vagrant jaguar was recorded in 23 locations in the Santa Rita Mountains.[56]

The jaguar prefers dense forest and typically inhabits dry

Former range

In the 19th century, the jaguar was still sighted at the North Platte River 48–80 km (30–50 mi) north of Longs Peak in Colorado, in coastal Louisiana, northern Arizona and New Mexico.[59] Multiple verified zoological reports of the jaguar are known in California, two as far north as Monterey in 1814 and 1826. The only record of an active jaguar den with breeding adults and kittens in the United States was in the Tehachapi Mountains of California prior to 1860.[60] The jaguar persisted in California until about 1860.[55] The last confirmed jaguar in Texas was shot in 1948, 4.8 km (3 mi) southeast of Kingsville, Texas.[61] In Arizona, a female was shot in the White Mountains in 1963. By the late 1960s, the jaguar was thought to have been extirpated in the United States. Arizona outlawed jaguar hunting in 1969, but by then no females remained, and over the next 25 years only two males were sighted and killed in the state. In 1996, a rancher and hunting guide from Douglas, Arizona came across a jaguar in the Peloncillo Mountains and became a researcher on jaguars, placing trail cameras, which recorded four more jaguars.[62]

Behavior and ecology

The jaguar is mostly active at night and during twilight.[36][63][64] However, jaguars living in densely forested regions of the

Ecological role

The adult jaguar is an

However, field work has shown this may be natural variability, and the population increases may not be sustained. Thus, theThe jaguar is

Hunting and diet

The jaguar is an

The jaguar's bite force allows it to pierce the

Between October 2001 and April 2004, 10 jaguars were monitored in the southern Pantanal. In the dry season from April to September, they killed prey at intervals ranging from one to seven days; and ranging from one to 16 days in the wet season from October to March.[80]

The jaguar uses a stalk-and-ambush strategy when hunting rather than chasing prey. The cat will slowly walk down forest paths, listening for and stalking prey before rushing or ambushing. The jaguar attacks from cover and usually from a target's blind spot with a quick pounce; the species' ambushing abilities are considered nearly peerless in the animal kingdom by both indigenous people and field researchers and are probably a product of its role as an apex predator in several different environments. The ambush may include leaping into water after prey, as a jaguar is quite capable of carrying a large kill while swimming; its strength is such that carcasses as large as a

Social activity

The jaguar is generally

The jaguar uses scrape marks, urine, and feces to

The size of home ranges depends on the level of deforestation and human population density. The home ranges of females vary from 15.3 km2 (5.9 sq mi) in the Pantanal to 53.6 km2 (20.7 sq mi) in the Amazon to 233.5 km2 (90.2 sq mi) in the Atlantic Forest. Male jaguar home ranges vary from 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) in the Pantanal to 180.3 km2 (69.6 sq mi) in the Amazon to 591.4 km2 (228.3 sq mi) in the Atlantic Forest and 807.4 km2 (311.7 sq mi) in the Cerrado.[86] Studies employing GPS telemetry in 2003 and 2004 found densities of only six to seven jaguars per 100 km (62 mi) in the Pantanal region, compared with 10 to 11 using traditional methods; this suggests the widely used sampling methods may inflate the actual numbers of individuals in a sampling area.[87] Fights between males occur but are rare, and avoidance behavior has been observed in the wild.[84] In one wetland population with degraded territorial boundaries and more social proximity, adults of the same sex are more tolerant of each other and engage in more friendly and co-operative interactions.[73]The jaguar roars/grunts for long-distance communication;[5][76] intensive bouts of counter-calling between individuals have been observed in the wild.[76] This vocalization is described as "hoarse" with five or six guttural notes.[5] Chuffing is produced by individuals when greeting, during courting, or by a mother comforting her cubs. This sound is described as low intensity snorts, possibly intended to signal tranquility and passivity.[88][89] Cubs have been recorded bleating, gurgling and mewing.[5]

Reproduction and life cycle

In captivity, the female jaguar is recorded to reach

In the Pantanal, breeding pairs were observed to stay together for up to five days. Females had one to two cubs.[97] The young are born with closed eyes but open them after two weeks. Cubs are

In 2001, a male jaguar killed and partially consumed two cubs in Emas National Park. DNA paternity testing of blood samples revealed that the male was the father of the cubs.[99] Two more cases of infanticide were documented in the northern Pantanal in 2013.[100] To defend against infanticide, the female may hide her cubs and distract the male with courtship behavior.[101]

Attacks on humans

The Spanish conquistadors feared the jaguar. According to Charles Darwin, the indigenous peoples of South America stated that people did not need to fear the jaguar as long as capybaras were abundant.[102] The first official record of a jaguar killing a human in Brazil dates to June 2008.[103] Two children were attacked by jaguars in Guyana.[104] The majority of known attacks on people happened when it had been cornered or wounded.[105]

Threats

The jaguar is threatened by

In 2002, it was estimated that the range of the jaguar had declined to about 46% of its range in the early 20th century.[53] In 2018, it was estimated that its range had declined by 55% in the last century. The only remaining stronghold is the Amazon rainforest, a region that is rapidly being fragmented by deforestation.[106] Between 2000 and 2012, forest loss in the jaguar range amounted to 83.759 km2 (32.340 sq mi), with fragmentation increasing in particular in corridors between Jaguar Conservation Units (JCUs).[107] By 2014, direct linkages between two JCUs in Bolivia were lost, and two JCUs in northern Argentina became completely isolated due to deforestation.[108]

In Mexico, the jaguar is primarily threatened by poaching. Its habitat is fragmented in northern Mexico, in the Gulf of Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula, caused by changes in land use, construction of roads and tourism infrastructure.[109] In Panama, 220 of 230 jaguars were killed in retaliation for predation on livestock between 1998 and 2014.[110] In Venezuela, the jaguar was extirpated in about 26% of its range in the country since 1940, mostly in dry savannas and unproductive scrubland in the northeastern region of Anzoátegui.[111] In Ecuador, the jaguar is threatened by reduced prey availability in areas where the expansion of the road network facilitated access of human hunters to forests.[112] In the Alto Paraná Atlantic forests, at least 117 jaguars were killed in Iguaçu National Park and the adjacent Misiones Province between 1995 and 2008.[113] Some Afro-Colombians in the Colombian Chocó Department hunt jaguars for consumption and sale of meat.[114] Between 2008 and 2012, at least 15 jaguars were killed by livestock farmers in central Belize.[115]

The international trade of jaguar skins boomed between the end of the

Conservation

The jaguar is listed on

In 1986, the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary was established in Belize as the world's first protected area for jaguar conservation.[125]

Jaguar Conservation Units

In 1999, field scientists from 18 jaguar range countries determined the most important areas for long-term jaguar conservation based on the status of jaguar population units, stability of prey base and quality of habitat. These areas, called "Jaguar Conservation Units" (JCUs), are large enough for at least 50 breeding individuals and range in size from 566 to 67,598 km2 (219 to 26,100 sq mi); 51 JCUs were designated in 36 geographic regions including:[53]

- the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra de Tamaulipas in Mexico

- the Selva Mayatropical forests extending over Mexico, Belize and Guatemala

- the Chocó–Darién moist forests from Honduras and Panama to Colombia

- Venezuelan Llanos

- northern Cerrado and Amazon basin in Brazil

- Tropical Andes in Bolivia and Peru

- Misiones Province in Argentina

Optimal routes of travel between core jaguar population units were identified across its range in 2010 to implement

In August 2012, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service set aside 3,392.20 km2 (838,232 acres) in Arizona and New Mexico for the protection of the jaguar.[129] The Jaguar Recovery Plan was published in April 2019, in which Interstate 10 is considered to form the northern boundary of the Jaguar Recovery Unit in Arizona and New Mexico.[130]

In Mexico, a national conservation strategy was developed from 2005 on and published in 2016.[109] The Mexican jaguar population increased from an estimated 4,000 individuals in 2010 to about 4,800 individuals in 2018. This increase is seen as a positive effect of conservation measures that were implemented in cooperation with governmental and non-governmental institutions and landowners.[131]

An evaluation of JCUs from Mexico to Argentina revealed that they overlap with high-quality habitats of about 1,500 mammals to varying degrees. Since co-occurring mammals benefit from the JCU approach, the jaguar has been called an umbrella species.[132] Central American JCUs overlap with the habitat of 187 of 304 regional endemic amphibian and reptile species, of which 19 amphibians occur only in the jaguar range.[133]

Approaches

In setting up protected reserves, efforts generally also have to be focused on the surrounding areas, as jaguars are unlikely to confine themselves to the bounds of a reservation, especially if the population is increasing in size. Human attitudes in the areas surrounding reserves and laws and regulations to prevent poaching are essential to make conservation areas effective.[134]

To estimate population sizes within specific areas and to keep track of individual jaguars, camera trapping and wildlife tracking telemetry are widely used, and feces are sought out with the help of detection dogs to study jaguar health and diet.[87][135]

Current conservation efforts often focus on educating ranch owners and promoting ecotourism.[136] Ecotourism setups are being used to generate public interest in charismatic animals such as the jaguar while at the same time generating revenue that can be used in conservation efforts. A key concern in jaguar ecotourism is the considerable habitat space the species requires. If ecotourism is used to aid in jaguar conservation, some considerations need to be made as to how existing ecosystems will be kept intact, or how new ecosystems will be put into place that are large enough to support a growing jaguar population.[137]

Conservationists and professionals in Mexico and the United States have established the 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) Northern Jaguar Reserve in northern Mexico. Advocacy for reintroduction of the jaguar to its former range in Arizona and New Mexico have been supported by documentation of natural migrations by individual jaguars into the southern reaches of both states, the recency of extirpation from those regions by human action, and supportive arguments pertaining to biodiversity, ecological, human, and practical considerations.[138]

In culture and mythology

In the

Sculptures with "

The

A

The jaguar is also used as a symbol in contemporary culture.[150] It is the national animal of Guyana and is featured in its coat of arms.[151]

See also

References

- ^ Hulbert Jr., Richard C.; Harrington, Arianna R. (9 April 2015) [20 March 2015]. Hulbert Jr., Richard C.; Valdes, Natali; Harrington, Arianna R. (eds.). "Panthera onca - Florida Vertebrate Fossils". Florida Museum. University of Florida. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ . Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ^ S2CID 253932256. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 June 2010.

- ISBN 9781890000097.

- Cambridge Dictionary. Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Labat, J.B. (1731). "Once, espèce de Tigre". Voyage du chevalier Des Marchais en Guinée, isles voisines, et à Cayenne, fait en 1725, 1726 & 1727. Vol. III. Amsterdam: La Compagnie. p. 285. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Ray, J. (1693). "Pardus an Lynx brasiliensis, Jaguara". Synopsis Methodica Animalium Quadrupedum et Serpentini Generis. Vulgarium Notas Characteristicas, Rariorum Descriptiones integras exhibens. London: S. Smith & B. Walford. p. 168.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). πάνθηρ. A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis onca". Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. I (Decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 42.

- ^ a b Pocock, R. I. (1939). "The races of jaguar (Panthera onca)". Novitates Zoologicae. 41: 406–422.

- ^ Blainville, H. M. D. de (1843). "F. leo nubicus". Ostéographie ou description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossils pour servir de base à la zoologie et la géologie (in French). Vol. II. Paris: J. B. Baillière et Fils. p. Plate VIII. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1857). "Notice of a new species of jaguar from Mazatlan, living in the gardens of the Zoological Society". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 25: 278.

- ^ Ameghino, F. (1888). "Formación Pampeana". Los Mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Pablo E. Coni é hijos. pp. 473–493.

- ^ a b Mearns, E. A. (1901). "The American Jaguars". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 14: 137–143.

- .

- ^ Goldman, E. A. (1932). "The jaguars of North America". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 45: 143–146.

- JSTOR 1373821.

- ^ S2CID 3916428.

- .

- from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 70–71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ PMID 26518481.

- PMID 20138224.

- PMID 22016768.

- ^ Argant, A. & Argant, J. (2011). "The Panthera gombaszogensis story: the contribution of the Château Breccia (Saône-et-Loire, Burgundy, France)". Quaternaire (Hors-serie 4): 247–269. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- S2CID 219914902.

- S2CID 252489047.

- S2CID 225408043.

- ^ .

- (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Rich, M.S. (1976). "The jaguar". Zoonoz. Vol. 49, no. 9. pp. 14–17.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ^ PMID 973541.

- ^ from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- PMID 20961899.

- ^ a b Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "Jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 118–122. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- PMID 15817436.

- .

- S2CID 35304260.

- ^ Brown, D.E. & Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. (2001). Borderland jaguars: tigres de la frontera. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

- S2CID 19021807.

- ^ .

- ^ Dinets, V. & Polechla, P.J. (2005). "First documentation of melanism in the jaguar (Panthera onca) from northern Mexico". Cat News. 42: 18. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006.

- ^ Núñez, M.C. & Jiménez, E.C. (2009). "A new record of a black jaguar, Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) in Costa Rica". Brenesia. 71: 67–68. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Sáenz-Bolaños, C.; Montalvo, V.; Fuller, T.K. & Carrillo, E. (2015). "Records of black jaguars at Parque Nacional Barbilla, Costa Rica". Cat News (62): 38–39.

- ^ Yacelga, M. & Craighead, K. (2019). "Melanistic jaguars in Panama". Cat News (70): 39–41. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ S2CID 3955250.

- JSTOR 3672607.

- ^ S2CID 161236104.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Caso, A. & Domínguez, E. F. (2018). "Confirmed presence of jaguar, ocelot and jaguarundi in the Sierra of San Carlos, Mexico". Cat News (68): 31–32.

- ^ S2CID 160927286.

- from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ISBN 9781477310021.

- Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the originalon 13 December 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- .

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.528.3603.

- .

- ^ Nijhawan, S. (2012). "Conservation units, priority areas and dispersal corridors for jaguars in Brazil" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue): 43–47. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- S2CID 86460403.

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- PMID 28133569.

- S2CID 10134066.

- ^ from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ S2CID 242197640.

- ^ Amit, R.; Gordillo-Chávez, E.J. & Bone, R. (2013). "Jaguar and puma attacks on livestock in Costa Rica". Human-Wildlife Interactions. 7 (1): 77–84.

- .

- ^ from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- JSTOR 1564460.

- ISBN 978-0-292-71604-9. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Schaller, G.B. & Vasconselos, J.M.C. (1978). "Jaguar predation on capybara" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 43: 296–301. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- .

- ^ Baker, W. K. Jr. "Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars". In Law, C. (ed.). Jaguar Species Survival Plan (PDF). Association of Zoos and Aquariums. pp. 8–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012.

- ^ JSTOR 2387967.

- S2CID 251713323.

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 28030568.

- ^ .

- S2CID 25252052.

- ^ Leuchtenberger, C.; Crawshaw, P. G.; Mourão, G. & Lehn, C. R. (2009). "Courtship behavior by Jaguars in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso do Sul". Natureza & Conservaç~ao Revista Brasileira de Conservaç~ao da Natureza. 7 (1): 218–222. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- PMID 383976.

- PMID 26399935.

- PMID 32092606.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (1976). "Gestation period and postnatal development in felids". In Eaton, R.L. (ed.). The world's cats. Vol. 3. Contributions to Biology, Ecology, Behavior and Evolution. Seattle: Carnivore Research Institute, Univ. Washington. pp. 143–165.

- ISBN 978-091218679-5.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ Egerton, J. (2006). "Jaguars: Magnificence in the Southwest" (PDF). Wild Tracks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- .

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- S2CID 239539707.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Porter, J. H. (1894). "The Jaguar". Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 174–195.

- ^ De Paula, R.; Campos Neto, M. F. & Morato, R. G. (2008). "First official record of Human killed by Jaguar in Brazil". Cat News (49): 31–32.

- PMID 25834674.

- ISBN 978-158834546-2.

- .

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- doi:10.3354/esr00840. Archived(PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-019976698-7. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Moreno, R.; Meyer, N.; Olmos, M.; Hoogesteijn, R. & Hoogesteijn, A.L. (2015). "Causes of jaguar killing in Panama – a long term survey using interviews" (PDF). Cat News (62): 40–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- PMID 29298311.

- hdl:11336/61266.

- ^ Balaguera-Reina, S. & Gonzalez-Maya, J.F. (2008). "Occasional jaguar hunting for subsistence in Colombian Chocó". Cat News (48): 5. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- PMID 33505226.

- ^ Broad, S. (1987). The harvest of and trade in Latin American spotted cats (Felidae) and otters (Lutrinae). Cambridge: IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041046.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 April 2012.

- .

- doi:10.1111/csp2.126. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- PMID 32484587.

- ^ Earth League International (2020). Unveiling the criminal networks behind jaguar trafficking in Bolivia (PDF) (Report). Amsterdam: IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Zapata Ríos, G.; Araguillin, E.; Cevallos, J.; Moreno, F.; Ortega, A.; Rengel, J. & Valarezo, N. (2014). Plan de Acción para la Conservación del Jaguar en el Ecuador [Action Plan for the Conservation of the Jaguar in Ecuador] (PDF) (in Spanish). Quito: Ministerio del Ambiente y Wildlife Conservation Society Ecuador. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Kerman, I. (2010). Felix, M.-L. (ed.). Exploitation of the jaguar, Panthera onca and other large forest cats in Suriname (PDF). Paramaribo: WWF Guianas.

- S2CID 85151201.

- (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-62417-071-3. Archived(PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service (2012). "Designation of Critical Habitat for Jaguar; Proposed Rule" (PDF). Federal Register. 77 (161): 50214–50242. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- .

- PMID 34613994.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- .

- PMID 26398115.

- ^ Furtado, M.M.; Carrillo-Percastegui, S.E.; Jácomo, A.T.A.; Powell, G.; Silveira, L.; Vynne, C. & Sollmann, R. (2008). "Studying jaguars in the wild: past experiences and future perspectives" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 4): 41–47. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the originalon 17 December 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- hdl:10072/125191.

- doi:10.1111/csp2.392.

- ISBN 978-1-4390-8476-2.

- ISBN 9781617037955.

- ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

- ^ Kruschek, M.H. (2003). The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PDF) (PhD thesis). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "nymy" (in Spanish). Muysc cubun Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "quyne" (in Spanish). Muysc cubun Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- S2CID 164201137.

- IFLScience. Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- JSTOR 124867.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8.

- ISBN 9781136605130.

- JSTOR 124867.

- ^ Khan, A. (2021). "National symbols: The Coat-Of-Arms". Guyana News and Information. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

External links

- "Jaguar Panthera onca". IUCN Cat Specialist Group.

- "Jaguars: Born free". BBC Natural World. 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- People and Jaguars a Guide for Coexistence

- Felidae Conservation Fund

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.