Trade

| Business administration |

|---|

| Management of a business |

|

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of credit or exchange, such as money. Though some economists characterize

In one modern view, trade exists due to specialization and the

Historically, openness to

Etymology

Trade is from

Commerce is derived from the Latin commercium, from cum "together" and merx, "merchandise."[8]

History

Prehistory

Trade originated from

In the Mediterranean region, the earliest contact between cultures involved members of the species Homo sapiens, principally using the Danube river, at a time beginning 35,000–30,000 BP.[10][11][12][13][need quotation to verify]

There is evidence of the exchange of obsidian and flint during the Stone Age. Trade in obsidian is believed to have taken place in New Guinea from 17,000 BCE.[15][16]

The earliest use of obsidian in the Near East dates to the Lower and Middle paleolithic.[17]

Robert Carr Bosanquet investigated trade in the Stone Age by excavations in 1901.[18][19] The first clear archaeological evidence of trade in manufactured goods is found in south west Asia.[20][21]

Archaeological evidence of obsidian use provides data on how this material was increasingly the preferred choice rather than chert from the late Mesolithic to Neolithic, requiring exchange as deposits of obsidian are rare in the Mediterranean region.[22][23][24]

Obsidian provided the material to make cutting utensils or tools, although since other more easily obtainable materials were available, use was exclusive to the higher status of the tribe using "the rich man's flint".[25] Interestingly, Obsidian has held its value relative to flint.

Early traders traded Obsidian at distances of 900 kilometres within the Mediterranean region.[26]

Trade in the Mediterranean during the Neolithic of Europe was greatest in this material.

The Sari-i-Sang mine in the mountains of Afghanistan was the largest source for trade of lapis lazuli.[33][34] The material was most largely traded during the Kassite period of Babylonia beginning 1595 BCE.[35][36]

Adam Smith traces the origins of commerce to the very start of

what they had for goods and services from each other. Anthropologists have found no evidence of barter systems that did not exist alongside systems of credit.Ancient History

Mediterranean and Near East

The earliest evidence of writing in is deeply bound up in trade, as a system of clay tokens used for accounting – found in Upper Euphrates valley in Syria dated to the 10th millennium BCE – is one of the earliest versions of writing.

Ebla was a prominent trading center during the third millennia BCE, with a network reaching into Anatolia and north Mesopotamia.[32][37][38][39]

Materials used for creating

The complaint tablet to Ea-nāṣir, dated 1750 BCE, documents the tribulations of a copper merchant at the time.

From the beginning of Greek

In ancient Greece Hermes was the god of trade[43][44] (commerce) and weights and measures.[45] In ancient Rome, Mercurius was the god of merchants, whose festival was celebrated by traders on the 25th day of the fifth month.[46][47] The concept of free trade was an antithesis to the will and economic direction of the sovereigns of the ancient Greek states. Free trade between states was stifled by the need for strict internal controls (via taxation) to maintain security within the treasury of the sovereign, which nevertheless enabled the maintenance of a modicum of civility within the structures of functional community life.[48][49]

The fall of the Roman empire and the succeeding

Indo-Pacific

The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was by the

Sea-faring Southeast Asians also established trade routes with

Mesoamerica

The emergence of exchange networks in the Pre-Columbian societies of and near to Mexico are known to have occurred within recent years before and after 1500 BCE.[61]

Trade networks reached north to Oasisamerica. There is evidence of established maritime trade with the cultures of northwestern South America and the Caribbean.

Middle Ages

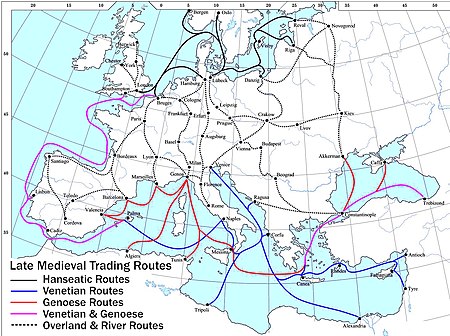

During the Middle Ages, commerce developed in Europe by trading luxury goods at trade fairs. Wealth became converted into movable wealth or capital. Banking systems developed where money on account was transferred across national boundaries. Hand to hand markets became a feature of town life and were regulated by town authorities.

Western Europe established a complex and expansive trade network with cargo ships being the main carrier of goods; Cogs and Hulks are two examples of such cargo ships.[62] Many ports would develop their own extensive trade networks. The English port city of Bristol traded with peoples from what is modern day Iceland, all along the western coast of France, and down to what is now Spain.[63]

During the Middle Ages, Central Asia was the economic center of the world.

From the Middle Ages, the

From the 8th to the 11th century, the

The Age of Sail and the Industrial Revolution

Portuguese explorer

From 1070 onward, kingdoms in West

Founded in 1352, the Bengal Sultanate was a major trading nation in the world and often referred to by Europeans as the wealthiest country with which to trade.[68]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Portuguese gained an economic advantage in the Kingdom of Kongo due to different philosophies of trade.[67] Whereas Portuguese traders concentrated on the accumulation of capital, in Kongo spiritual meaning was attached to many objects of trade. According to economic historian Toby Green, in Kongo "giving more than receiving was a symbol of spiritual and political power and privilege."[67]

In the 16th century, the

In 1776,

controls "dupery", which hurt the trading nation as a whole for the benefit of specific industries.In 1799, the

19th century

In 1817,

- When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit.

The ascendancy of free trade was primarily based on national advantage in the mid 19th century. That is, the calculation made was whether it was in any particular country's self-interest to open its borders to imports.

20th century

The Great Depression was a major economic recession that ran from 1929 to the late 1930s. During this period, there was a great drop in trade and other economic indicators.

The lack of free trade was considered by many as a principal cause of the depression causing stagnation and inflation.

The European Union became the world's largest exporter of manufactured goods and services, the biggest export market for around 80 countries.[72]

21st century

Today, trade is merely a subset within a complex system of

Free trade

Free trade is a policy by which a government does not discriminate against imports or exports by applying tariffs or subsidies. This policy is also known as laissez-faire policy. This kind of policy does not necessarily imply because a country will then abandon all control and taxation of imports and exports.[73]

Free trade advanced further in the late 20th century and early 2000s:

- 1992 labour.

- January 1, 1994 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect.

- 1994 The GATT Marrakech Agreementspecified formation of the WTO.

- January 1, 1995 most favored nationtrading status between all signatories.

- EC was transformed into the European Union, which accomplished the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in 2002, through introducing the Euro, and creating this way a real single market between 13 member states as of January 1, 2007.

- Central American Free Trade Agreementwas signed; It includes the United States and the Dominican Republic.

Perspectives

Protectionism

Protectionism is the policy of restraining and discouraging trade between states and contrasts with the policy of free trade. This policy often takes the form of tariffs and restrictive quotas. Protectionist policies were particularly prevalent in the 1930s, between the Great Depression and the onset of World War II.

Religion

Islamic teachings encourage trading (and condemn usury or interest).[74][75]

Development of money

The first instances of money were objects with intrinsic value. This is called commodity money and includes any commonly available commodity that has intrinsic value; historical examples include pigs, rare seashells, whale's teeth, and (often) cattle. In medieval Iraq, bread was used as an early form of money. In the Aztec Empire, under the rule of Montezuma cocoa beans became legitimate currency.[78]

Currency was introduced as standardised money to facilitate a wider exchange of goods and services. This first stage of currency, where metals were used to represent stored value, and symbols to represent commodities, formed the basis of trade in the Fertile Crescent for over 1500 years.

Numismatists have examples of coins from the earliest large-scale societies, although these were initially unmarked lumps of precious metal.[79]

Trends

Doha rounds

The Doha round of World Trade Organization negotiations aimed to lower

China

Beginning around 1978, the government of the

The reforms proved spectacularly successful in terms of increased output, variety, quality, price and demand. In real terms, the economy doubled in size between 1978 and 1986, doubled again by 1994, and again by 2003. On a real per capita basis, doubling from the 1978 base took place in 1987, 1996 and 2006. By 2008, the economy was 16.7 times the size it was in 1978, and 12.1 times its previous per capita levels. International trade progressed even more rapidly, doubling on average every 4.5 years. Total two-way trade in January 1998 exceeded that for all of 1978; in the first quarter of 2009, trade exceeded the full-year 1998 level. In 2008, China's two-way trade totaled US$2.56 trillion.[81]

In 1991 China joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group, a trade-promotion forum.[82] In 2001, it also joined the World Trade Organization.[83]

International trade

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

Empirical evidence for the success of trade can be seen in the contrast between countries such as South Korea, which adopted a policy of export-oriented industrialization, and India, which historically had a more closed policy. South Korea has done much better by economic criteria than India over the past fifty years, though its success also has to do with effective state institutions.[84]

Trade sanctions

Fair trade

The "

Importing firms voluntarily adhere to fair trade standards or governments may enforce them through a combination of

See also

Notes

- JSTOR 137133.

- S2CID 62781399. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2004-03-07. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ISBN 978-0-324-22519-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-22. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

Five types of nonstore retailing will be discussed: street peddling, direct selling, mail-order, automatic-merchandising machine operators, and electronic shopping.

- ^ "Distribution Services". Foreign Agricultural Service. 2000-02-09. Archived from the original on 2006-05-15. Retrieved 2006-04-04.

- ISSN 0212-6109.

- ^ Federico, Giovanni; Tena-Junguito, Antonio (2018-07-28). "The World Trade Historical Database". VoxEU.org. Archived from the original on 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-25, retrieved 2019-10-07

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 766.

- ^ Watson (2005), Introduction.

- ISBN 978-1-60606-057-5, archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-11, retrieved 2019-09-07,

[...] the Danube played an extremely important role in connecting East and West before the Mediterranean became the main link between these regions. This period runs for about 25,000 years, from 35,000/30,000 to around 10,000/8,000 before the present.

- ^ Compare:

Barbier, Edward (2015). "The Origins of Economic Wealth". Nature and Wealth: Overcoming Environmental Scarcity and Inequality. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403391. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

Even before domestication of plants and animals occurred, long-distance trading networks were prominent among some hunter-gathering societies, such as the Natufians and other sedentary populations who inhabited the Eastern Mediterranean around 12,000–10,000 BC.

- ISBN 978-1258868482. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ National Maritime Historical Society. Sea History, Issues 13–25 Archived 2018-09-15 at the Wayback Machine published by National Maritime Historical Society 1979. Retrieved 2012-06-26

- ^ Hans Biedermann, James Hulbert (trans.), Dictionary of Symbolism Cultural Icons and the Meanings behind Them, p. 54.

- ^ Lowder, Gary George (1970). Studies in volcanic petrology: I. Talasea, New Guinea. II. Southwest Utah. University of California. Archived from the original on 2021-02-05.

- ISBN 978-0191579042. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2019.was traded from at least 17 000 BC.

[...] obsidian from Talasea

- HIH Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito – Essays on Anatolian Archaeology Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback MachineOtto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1993 Retrieved 2012-06-16

- ^ Vernon Horace Rendall, ed. (1904). The Athenaeum. J. Francis. Archived from the original on 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ISBN 1-60506-375-4Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ISBN 978-0-415-42476-9, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-15

- ^ P Singh – Neolithic cultures of western Asia Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine Seminar Press, 20 Aug 1974

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-84241-9, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-11

- ISBN 0-306-46279-6Retrieved 2012-06-28

- ISBN 1-934536-02-4Retrieved 2012-06-28

- ISBN 978-1134095803. Archivedfrom the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

[...] modern observers have sometimes referred to obsidian as 'rich man's flint.'

- .

- ^ D Harper – etymology online Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ISBN 978-1-85109-930-6, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-11

- ^ T A H Wilkinson – Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security Archived 2022-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ secondary – [1] Archived 2022-05-23 at the Wayback Machine + [[iarchive:emergenceofcivil0000unse/page/441|]] + [2] Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine + [3] Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine + [4] Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-1-85109-930-6, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-11

- ^ ISBN 978-0-631-23268-1, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-22

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson – Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security Routledge, 8 Aug 2001 Retrieved 2012-07-03 [dead link]

- ISBN 0-520-07308-8. Archived from the originalon 2022-08-07. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ISBN 1-134-26128-4

- ISBN 0-19-518364-9

- ISBN 978-1-61530-329-8, retrieved 2012-06-15

- ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5, archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-05, retrieved 2012-06-28

- ^ B.Gascoigne et al. – History World .net

- ^ Ivan Dikov (July 12, 2015). "Bulgarian Archaeologists To Start Excavations of Ancient Greek Emporium in Thracians' the Odrysian Kingdom". Archaeology in Bulgaria. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

An emporium (in Latin; "emporion" in Greek) was a settlement reserved as a trading post, usually for the Ancient Greeks, on the territory of another ancient nation, in this case, the Ancient Thracian Odrysian Kingdom (5th century BC – 1st century AD), the most powerful Thracian state.

- ^ Jan David Bakker, Stephan Maurer, Jörn-Steffen Pischke and Ferdinand Rauch. 2021. "Of Mice and Merchants: Connectedness and the Location of Economic Activity in the Iron Age." Review of Economics and Statistics 103 (4): 652–665.

- ^ Pax Romana let average villagers throughout the Empire conduct day-to-day affairs without fear of armed attack.

- ISBN 0-521-26931-8Retrieved 2012-06-25

- ISBN 0-940262-26-6Retrieved 2012-06-25

- ISBN 0-19-511206-7Retrieved 2012-06-26

- ISBN 1-4344-7028-8Retrieved 2012-06-25

- ISBN 0-87398-255-XRetrieved 2012-06-25

- ISBN 0-8196-0150-0

- ^ Cambridge dictionaries online[full citation needed]

- ^ Gil, Moshe. "The Rādhānite Merchants and the Land of Rādhān". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 17 (3): 299.

- ^ ISBN 9783319338224. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan's relations with the Philippines date back millennia, so it's a mystery that it's not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^ Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^ Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). "Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction". Semantic Scholar.

- ^ Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- ISBN 0415100542.

- ISBN 978-0890961070.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- ^ "Aztec Hoe Money". National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ K G Hirth – American Antiquity Vol. 43, No. 1 (Jan., 1978), pp. 35–45 Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2012-06-28

- ^ McGrail, Sean (2001). Boats of the World : From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Poole, Austin Lane (1958). Medieval England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Beckwith (2011), p. xxiv.

- ^ "Italian Trade Cities | Western Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ "History of Genoa, Rival to Venice". Odyssey Traveller. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ OCLC 1051687994.

- ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- ISBN 9780202309699.

- ^ (secondary) British Broadcasting Corporation – history Archived 2019-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-575-06150-2

- ^ "EU position in world trade". European Commission. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ "Free-trade zone | international trade | Britannica". Archived from the original on 2023-02-16. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ Nomani & Rahnema (1994), p. ?. "I want nine out of ten people from my Ummah (nation) as traders" and "Trader, who did trading in truth, and sold the right quantity and quality of goods, he will stand along with Prophets and Martyrs, on Judgment day".

- ^ Quran 4:29: "O believers! Do not devour one another’s wealth illegally, but rather trade by mutual consent."

Quran 2:275: "But Allah has permitted trading and forbidden interest." - ^ Leviticus 19:13

- ^ Leviticus 19:35

- ^ "Is There Slavery In Your Chocolate?". Archived from the original on November 28, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2005.

- ^ Gold was an especially common form of early money, as described in Davies (2002).

- ^ "Documents & Reports– The World Bank". documents.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 2020-05-26. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ Division, US Census Bureau Foreign Trade. "Foreign Trade: Data". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ "Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation". Archived from the original on 2018-09-28. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ "China and the WTO". Archived from the original on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Storper, Michael (2000). "Globalization, localization and trade". The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography: 146–165.

- ^ "U.S.–Cuba Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ LLC, Helix Consulting. "On temporary ban on imports of goods having Turkish origin". www.gov.am. Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ "Should trade be considered a human right?". COPLA. 9 December 2008. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

- ^ "FAIRTRADE Certification Mark. Guidelines Issue 1 – Autumn 2011" (PDF). Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International e.V. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ISSN 1742-2043.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-4416-4.

- Davies, Glyn (2002) [1995]. Ideas: A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day. Cardiff: ISBN 978-0-7083-1773-0.

- Nomani, Farhad; Rahnema, Ali (1994). Islamic Economic Systems. New Jersey: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-058-0.

- Paine, Lincoln (2013). The Sea and Civilisation: a Maritime History of the World. Atlantic. (Covers sea-trading over the whole world from ancient times)

- Rössner, Philipp, Economy / Trade, EGO – European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2017, retrieved: March 8, 2021 (pdf).

- ISBN 978-0-06-621064-3.

External links

Media related to Trading at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trading at Wikimedia Commons- Agritrade Resource material on trade by ACP countries

- World Bank's World Integrated Trade Solution provides summary trade statistics and custom query features

- World Bank's Preferential Trade Agreement Database