Styrene

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Styrene[2]

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ethenylbenzene[1] | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|||

| 1071236 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.002.592 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 2991 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

RTECS number

|

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2055 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H8 | |||

| Molar mass | 104.15 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | colorless oily liquid | ||

| Odor | sweet, floral[3] | ||

| Density | 0.909 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −30 °C (−22 °F; 243 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 145 °C (293 °F; 418 K) | ||

| 0.03% (20 °C)[3] | |||

| log P | 2.70[4] | ||

| Vapor pressure | 5 mmHg (20 °C)[3] | ||

| −6.82×10−5 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.5469 | ||

| Viscosity | 0.762 cP at 20 °C | ||

| Structure | |||

| 0.13 D | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

flammable, toxic, probably carcinogenic

| ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H226, H315, H319, H332, H361, H372 | |||

| P201, P202, P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P281, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P312, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P312, P314, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P370+P378, P403+P235, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 31 °C (88 °F; 304 K) | ||

Explosive limits

|

0.9–6.8%[3] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

2194 ppm (mouse, 4 h) 5543 ppm (rat, 4 h)[5] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

10,000 ppm (human, 30 min) 2771 ppm (rat, 4 h)[5] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 100 ppm C 200 ppm 600 ppm (5-minute maximum peak in any 3 hours)[3] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 50 ppm (215 mg/m3) ST 100 ppm (425 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

700 ppm[3] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | MSDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related styrenes;

related aromatic compounds |

polystyrene, stilbene; ethylbenzene | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

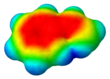

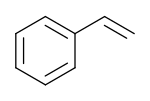

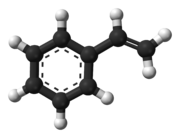

Styrene is an organic compound with the chemical formula C6H5CH=CH2. Its structure consists of a vinyl group as substituent on benzene. Styrene is a colorless, oily liquid, although aged samples can appear yellowish. The compound evaporates easily and has a sweet smell, although high concentrations have a less pleasant odor.[vague] Styrene is the precursor to polystyrene and several copolymers, and is typically made from benzene for this purpose. Approximately 25 million tonnes of styrene were produced in 2010,[6] increasing to around 35 million tonnes by 2018.

Natural occurrence

Styrene is named after

.History

In 1839, the German apothecary Eduard Simon isolated a volatile liquid from the resin (called storax or styrax (Latin)) of the American sweetgum tree (Liquidambar styraciflua). He called the liquid "styrol" (now called styrene).[8][9] He also noticed that when styrol was exposed to air, light, or heat, it gradually transformed into a hard, rubber-like substance, which he called "styrol oxide".[10]

By 1845, the German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann and his student John Buddle Blyth had determined styrene's empirical formula: C8H8.[11] They had also determined that Simon's "styrol oxide" – which they renamed "metastyrol" – had the same empirical formula as styrene.[12] Furthermore, they could obtain styrene by dry-distilling "metastyrol".[13]

In 1865, the German chemist

In 1845, French chemist Emil Kopp suggested that the two compounds were identical,[16] and in 1866, Erlenmeyer suggested that both "cinnamol" and styrene might be vinylbenzene.[17] However, the styrene that was obtained from cinnamic acid seemed different from the styrene that was obtained by distilling storax resin: the latter was optically active.[18] Eventually, in 1876, the Dutch chemist van 't Hoff resolved the ambiguity: the optical activity of the styrene that was obtained by distilling storax resin was due to a contaminant.[19]

Industrial production

From ethylbenzene

The vast majority of styrene is produced from

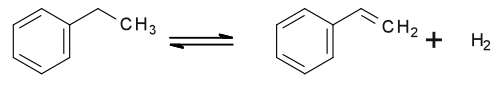

By dehydrogenation

Around 80% of styrene is produced by the

The crude ethylbenzene/styrene product is then purified by distillation. As the difference in boiling points between the two compounds is only 9 °C at ambient pressure this necessitates the use of a series of distillation columns. This is energy intensive and is further complicated by the tendency of styrene to undergo thermally induced polymerisation into polystyrene,

Via ethylbenzene hydroperoxide

Styrene is also co-produced commercially in a process known as POSM (

Other industrial routes

Pyrolysis gasoline extraction

Extraction from pyrolysis gasoline is performed on a limited scale.[20]

From toluene and methanol

Styrene can be produced from

From benzene and ethane

Another route to styrene involves the reaction of benzene and ethane. This process is being developed by Snamprogetti and Dow. Ethane, along with ethylbenzene, is fed to a dehydrogenation reactor with a catalyst capable of simultaneously producing styrene and ethylene. The dehydrogenation effluent is cooled and separated and the ethylene stream is recycled to the alkylation unit. The process attempts to overcome previous shortcomings in earlier attempts to develop production of styrene from ethane and benzene, such as inefficient recovery of aromatics, production of high levels of heavies and tars, and inefficient separation of hydrogen and ethane. Development of the process is ongoing.[26]

Laboratory synthesis

A laboratory synthesis of styrene entails the decarboxylation of cinnamic acid:[27]

- C6H5CH=CHCO2H → C6H5CH=CH2 + CO2

Styrene was first prepared by this method.[28]

Polymerization

The presence of the vinyl group allows styrene to

Hazards

Autopolymerisation

As a liquid or a gas, pure styrene will polymerise spontaneously to polystyrene, without the need of external

Health effects

Styrene is regarded as a "known

On 10 June 2011, the US National Toxicology Program has described styrene as "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen".[39][40] However, a STATS author describes[41] a review that was done on scientific literature and concluded that "The available epidemiologic evidence does not support a causal relationship between styrene exposure and any type of human cancer".[42] Despite this claim, work has been done by Danish researchers to investigate the relationship between occupational exposure to styrene and cancer. They concluded, "The findings have to be interpreted with caution, due to the company based exposure assessment, but the possible association between exposures in the reinforced plastics industry, mainly styrene, and degenerative disorders of the nervous system and pancreatic cancer, deserves attention".[43] In 2012, the Danish EPA concluded that the styrene data do not support a cancer concern for styrene.[44] The US EPA does not have a cancer classification for styrene,[45] but it has been the subject of their Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) program.[46]

The

The neurotoxic

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/7501#section=IUPAC-Name&fullscreen=true

- ^ a b c d e f g NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0571". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Styrene". www.chemsrc.com.

- ^ a b "Styrene". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "New Process for Producing Styrene Cuts Costs, Saves Energy, and Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions" (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2013.

- from the original on 14 February 2018.

- ^ Simon, E. (1839) "Ueber den flüssigen Storax (Styrax liquidus)" (On liquid storax (Styrax liquidus), Annalen der Chemie, 31 : 265–277. From p. 268: "Das flüchtige Oel, für welches ich den Namen Styrol vorschlage, … " (The volatile oil, for which I suggest the name "styrol", … )

- ^ For further details of the history of styrene, see: F. W. Semmler, Die ätherischen Öle nach ihren chemischen Bestandteilen unter Berücksichtigung der geschichtlichen Entwicklung [The volatile liquids according to their chemical components with regard to historical development], vol. 4 (Leipzig, Germany, Veit & Co., 1907), § 327. Styrol, pp. 24-28. Archived 1 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (Simon, 1839), p. 268. From p. 268: "Für den festen Rückstand würde der Name Styroloxyd passen." (For the solid residue, the name "styrol oxide" would fit.)

- ^

See:

- Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilhelm (1845a). "On styrole, and some of the products of its decomposition". Memoirs and Proceedings of the Chemical Society of London. 2: 334–358. from the original on 1 May 2018.; see p. 339.

- Reprinted in: Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilhelm (August 1845b). "On styrole, and some of the products of its decomposition". Philosophical Magazine. 3rd series. 27 (178): 97–121. .; see p. 102.

- German translation: Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilh. (1845c). "Ueber das Styrol und einige seiner Zersetzungsproducte" [On styrol and some of its decomposition products]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 53 (3): 289–329. .; see p. 297.

- Note that Blyth and Hofmann state the empirical formula of styrene as C16H8 because at that time, some chemists used the wrong atomic mass for carbon (6 instead of 12).

- ^ (Blyth and Hofmann, 1845a), p. 348. From p. 348: "Analysis as well as synthesis has equally proved that styrol and the vitreous mass (for which we propose the name of metastyrol) possess the same constitution per cent."

- ^ (Blyth and Hofmann, 1845a), p. 350

- ^ Erlenmeyer, Emil (1865) "Ueber Distyrol, ein neues Polymere des Styrols" (On distyrol, a new polymer of styrol), Annalen der Chemie, 135 : 122–123.

- ^ Berthelot, M. (1866) "Sur les caractères de la benzine et du styrolène, comparés avec ceux des autres carbures d'hydrogène" (On the characters of benzene and styrene, compared with those of other hydrocarbons), Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris, 2nd series, 6 : 289–298. From p. 294: "On sait que le styrolène chauffé en vase scellé à 200°, pendant quelques heures, se change en un polymère résineux (métastyrol), et que ce polymère, distillé brusquement, reproduit le styrolène." (One knows that styrene [when] heated in a sealed vessel at 200 °C, for several hours, is changed into a resinous polymer (metastyrol), and that this polymer, [when] distilled abruptly, reproduces styrene.)

- ^ Kopp, E. (1845), "Recherches sur l'acide cinnamique et sur le cinnamène" Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Investigations of cinnamic acid and cinnamen), Comptes rendus, 21 : 1376–1380. From p. 1380: "Je pense qu'il faudra désormais remplacer le mot de styrol par celui de cinnamène, et le métastyrol par le métacinnamène." (I think that henceforth one will have to replace the word "styrol" with that of "cinnamène", and "metastyrol" with "metacinnamène".)

- ^ Erlenmeyer, Emil (1866) "Studien über die s.g. aromatischen Säuren" (Studies of the so-called aromatic acids), Annalen der Chemie, 137 : 327–359; see p. 353.

- Macmillan and Co. pp. 51–52. Archived from the originalon 10 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2016.])

- ^ van 't Hoff, J. H. (1876) "Die Identität von Styrol und Cinnamol, ein neuer Körper aus Styrax" (The identity of styrol and cinnamol, a new substance from styrax), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 9 : 5-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-3527306732.

- .

- ^ PMID 15669866.

- .

- ^ "Welcome to ICIS". www.icis.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Stephen K. Ritter, Chemical & Engineering News, 19 March 2007, p.46.

- ^ "CHEMSYSTEMS.COM" (PDF). www.chemsystems.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Abbott, T.W.; Johnson, J.R. (1941). "Phenylethylene (Styrene)". Organic Syntheses

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 440. - .

- ^ "Report on the investigation of the cargo tank explosion and fire on board the chemical tanker Stolt Groenland" (PDF). e UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch.

- ^ "Vizag Gas Leak Live News: Eleven dead, several hospitalised after toxic gas leak from LG Polymers plant". The Economic Times. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Hundreds in hospital after leak at Indian chemical factory closed by lockdown". The Guardian. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- MSDS. Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- US EPA. December 1994. Archived(PDF) from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - PMID 809262.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "EPA settles case against Phoenix company for toxic chemical reporting violations". US Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "EPA Fines California Hot Tub Manufacturer for Toxic Chemical Release Reporting Violations". US Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Harris, Gardiner (10 June 2011). "Government Says 2 Common Materials Pose Risk of Cancer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (10 June 2011). "12th Report on Carcinogens". National Toxicology Program. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "STATS: Styrene in the Crosshairs: Competing Standards Confuse Public, Regulators". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Boffetta, P., et al., Epidemiologic Studies of Styrene and Cancer: A Review of the Literature Archived 9 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, J. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Nov.2009, V.51, N.11.

- PMID 7795754.

- ^ Danish EPA 2011 review "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Styrene (CASRN 100-42-5) | Region | US EPA". Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009. US environmental protection agency. Section I.B.4 relates to neurotoxicology.

- ^ "EPA IRIS track styrene page". epa.gov. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Styrene entry in National Toxicology Program's Thirteenth Report on Carcinogens" (PDF). nih.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- S2CID 48357020.

- ^ "After 40 years in limbo: Styrene is probably carcinogenic". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- PMID 2155647.

- PMID 1666820.

- S2CID 7463900.

- S2CID 34799773.

- ^ PMID 16105249.

- ^ PMID 24929234.

- OCLC 792746283.

- S2CID 7030810.

- S2CID 207571026.

- PMID 24180784.

- .