Low back pain

| Low back pain | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lower back pain, lumbago |

rehabilitation medicine | |

| Usual onset | 20 to 40 years of age[1] |

| Duration | ~65% get better in 6 weeks[2] |

| Types | Acute (less than 6 weeks), sub-chronic (6 to 12 weeks), chronic (more than 12 weeks)[3] |

| Causes | Usually non-specific, occasionally significant underlying cause[1][4] |

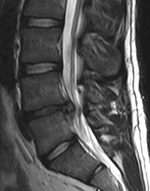

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging (if red flags)[5] |

| Treatment | Continued normal activity, non-medication based treatments, NSAIDs[2][6] |

| Frequency | ~25% in any given month[7][8] |

Low back pain or

In most episodes of low back pain a specific underlying cause is not identified or even looked for, with the pain believed to be due to mechanical problems such as

The symptoms of low back pain usually improve within a few weeks from the time they start, with 40–90% of people recovered by six weeks.

Approximately 9–12% of people (632 million) have low back pain at any given point in time,

Signs and symptoms

In the common presentation of acute low back pain, pain develops after movements that involve lifting, twisting, or forward-bending. The symptoms may start soon after the movements or upon waking up the following morning. The description of the symptoms may range from tenderness at a particular point, to diffuse pain. It may or may not worsen with certain movements, such as raising a leg, or positions, such as sitting or standing. Pain radiating down the legs (known as sciatica) may be present. The first experience of acute low back pain is typically between the ages of 20 and 40. This is often a person's first reason to see a medical professional as an adult.[1] Recurrent episodes occur in more than half of people[26] with the repeated episodes being generally more painful than the first.[1]

Other problems may occur along with low back pain. Chronic low back pain is associated with sleep problems, including a greater amount of time needed to fall asleep, disturbances during sleep, a shorter duration of sleep, and less satisfaction with sleep.[27] In addition, a majority of those with chronic low back pain show symptoms of depression[17] or anxiety.[19]

Causes

Low back pain is not a specific disease but rather a complaint that may be caused by a large number of underlying problems of varying levels of seriousness.

Women may have acute low back pain from medical conditions affecting the female reproductive system, including endometriosis, ovarian cysts, ovarian cancer, or uterine fibroids.[32] Nearly half of all pregnant women report pain in the low back during pregnancy, due to changes in their posture and center of gravity causing muscle and ligament strain.[33]

Low back pain can be broadly classified into four main categories:

- Musculoskeletal – mechanical (including compression fracture

- Inflammatory – HLA-B27 associated arthritis including ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammation within the reproductive system, and inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy – bone metastasis from lung, breast, prostate, thyroid, among others

- Infectious – osteomyelitis, abscess, urinary tract infection.[34]

Pathophysiology

Back structures

The lumbar (or lower back) region is the area between the lower ribs and gluteal fold which includes five lumbar

The multifidus muscles run up and down along the back of the spine, and are important for keeping the spine straight and stable during many common movements such as sitting, walking and lifting.[11] A problem with these muscles is often found in someone with chronic low back pain, because the back pain causes the person to use the back muscles improperly in trying to avoid the pain.[36] The problem with the multifidus muscles continues even after the pain goes away, and is probably an important reason why the pain comes back.[36] Teaching people with chronic low back pain how to use these muscles is recommended as part of a recovery program.[36]

An intervertebral disc has a

Pain sensation

Pain is generally an unpleasant feeling in response to an

Parts of the pain sensation and processing system may not function properly; creating the feeling of pain when no outside cause exists, signaling too much pain from a particular cause, or signaling pain from a normally non-painful event. Additionally, the pain modulation mechanisms may not function properly. These phenomena are involved in chronic pain.[11]

Diagnosis

As the structure of the low back is complex, the reporting of pain is

Classification

There are a number of ways to classify low back pain with no consensus that any one method is best.

Low back pain may be classified based on the signs and symptoms. Diffuse pain that does not change in response to particular movements, and is localized to the lower back without radiating beyond the

The symptoms can also be classified by duration as acute, sub-chronic (also known as sub-acute), or chronic. The specific duration required to meet each of these is not universally agreed upon, but generally pain lasting less than six weeks is classified as acute, pain lasting six to twelve weeks is sub-chronic, and more than twelve weeks is chronic.[3] Management and prognosis may change based on the duration of symptoms.

Red flags

| Red flag[40] | Possible cause[1] |

|---|---|

| Previous history of cancer | Cancer |

Unintentional weight loss

| |

| Loss of bladder or bowel control | Cauda equina syndrome |

| Significant motor weakness or sensory problems | |

| Loss of sensation in the buttocks (saddle anesthesia) | |

| Significant trauma related to age | Fracture |

| Chronic corticosteroid use | |

| Osteoporosis | |

| Severe pain after lumbar surgery in past year |

Infection |

| Fever | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Immunosuppression | |

Intravenous drug use

|

The presence of certain signs, termed red flags, indicate the need for further testing to look for more serious underlying problems, which may require immediate or specific treatment.

The usefulness of many red flags is poorly supported by evidence.[44][42] The most useful for detecting a fracture are: older age, corticosteroid use, and significant trauma especially if it results in skin markings.[44] The best determinant of the presence of cancer is a history of the same.[44]

With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain are typically treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the cause.[3][1] Efforts to uncover factors that might complicate the diagnosis, such as depression, substance abuse, or an agenda concerning insurance payments may be helpful.[5]

Tests

Imaging is indicated when there are red flags, ongoing neurological symptoms that do not resolve, or ongoing or worsening pain.

Complaints of low back pain are one of the most common reasons people visit doctors.

Prevention

Studies have proven that interventions aimed to reduce pain and functional disability need to be accompanied by psychological interventions to improve a patient's motivation and attitude toward their recovery. Education about an injury and how it can effect a person's mental health is just as important as the physical rehabilitation. However, all of these interventions should occur in partnership with a structured therapeutic exercise program and assistance from a trained physical therapist. [59]

Management

Most people with acute or subacute low back pain improve over time no matter the treatment.

For those with sub-chronic or chronic low back pain, multidisciplinary treatment programs may help.

Physical therapy stabilization exercises for lumbar spine and manual therapy have shown decrease in pain symptoms in patients. Manual therapy and stabilization effects have similar effects on low back pain which overweighs the effects of general exercises.[62] The most effective types of exercise to improve low back pain symptoms are core strengthening and mixed exercise types. An appropriate type of exercise recommended is an aerobic exercise program for 12 hours of exercise over a duration of 8 weeks.[63]

Distress due to low back pain contributes significantly to overall pain and disability experienced. Therefore, treatment strategies that aim to change beliefs and behaviours, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy can be of use.[54]

Access to care as recommended in medical guidelines varies considerably from the care that most people with low back pain receive globally. This is due to factors such as availability, access and payment models (eg. insurance, health-care systems).[64]

Physical management

Management of acute low back pain

Increasing general physical activity has been recommended, but no clear relationship to pain or disability or returning to work has been found when used for the treatment of an acute episode of pain.[55][65][66] For acute pain, low- to moderate-quality evidence supports walking.[67] Aerobic exercises like progressive walking appears useful for subacute and acute low back pain, is strongly recommended for chronic low back pain, and is recommended after surgery.[57] Directional exercises, which try to limit low back pain, are recommended in sub-acute, chronic and radicular low back pain. These exercises only work if they are limiting low back pain.[57] Exercise programs that incorporate stretching only are not recommended for acute low back pain. Stretching, especially with limited range of motion, can impede future progression of treatment like limiting strength and limiting exercises.[57] Yoga and Tai chi are not recommended in case of acute or subacute low back pain, but are recommended in case of chronic back pain.[57]

Treatment according to McKenzie method is somewhat effective for recurrent acute low back pain, but its benefit in the short term does not appear significant.[1] There is tentative evidence to support the use of heat therapy for acute and sub-chronic low back pain[68] but little evidence for the use of either heat or cold therapy in chronic pain.[69] Weak evidence suggests that back belts might decrease the number of missed workdays, but there is nothing to suggest that they help with the pain.[70] Ultrasound and shock wave therapies do not appear effective and therefore are not recommended.[71][72] Lumbar traction lacks effectiveness as an intervention for radicular low back pain.[73] It is also unclear whether lumbar supports are an effective treatment intervention.[74]

Management of chronic low back pain

Patients with chronic low back pain receiving multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation (MBR) programs are likely to experience less pain and disability than those receiving usual care or a physical treatment. MBR also has a positive influence on work status of the patient compared to physical treatment. Effects are of a modest magnitude and should be balanced against the time and resource requirements of MBR programs.[85]

Peripheral nerve stimulation, a minimally-invasive procedure, may be useful in cases of chronic low back pain that do not respond to other measures, although the evidence supporting it is not conclusive, and it is not effective for pain that radiates into the leg.[86] Evidence for the use of shoe insoles as a treatment is inconclusive.[58] Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has not been found to be effective in chronic low back pain.[87] There has been little research that supports the use of lumbar extension machines and thus they are not recommended.[57]

Medications

If initial management with non–medication based treatments is insufficient, medication may be recommended.[6] As pain medications are only somewhat effective, expectations regarding their benefit may differ from reality, and this can lead to decreased satisfaction.[17]

The medication typically prescribed first are acetaminophen (paracetamol),

Systemic corticosteriods are sometimes suggested for low back pain and may have a small benefit in the short-term for radicular low back pain, however, the benefit for non-radicular back pain and the optimal dose and length of treatment is unclear.[95]

As of 2022, the CDC has released a guideline for prescribed opioid use in the management of chronic pain.[13] It states that opioid use is not the preferred treatment when managing chronic pain due to the excessive risks involved, including high risks of addiction, accidental overdose and death.[14] Specialist groups advise against general long-term use of opioids for chronic low back pain.[17][96] If the pain is not managed adequately, short-term use of opioids such as morphine may be suggested,[97][17] although low back pain outcomes are poorer in the long-term.[54] If prescribed, a person and their clinician should have a realistic plan to discontinue its use in the event that the risks outweigh the benefit.[98] These medications carry a risk of addiction, may have negative interactions with other drugs, and have a greater risk of side effects, including dizziness, nausea, and constipation.[17] Opioid treatment for chronic low back pain increases the risk for lifetime illicit drug use[99] and the effect of long-term use of opioids for lower back pain is unknown.[100] For older people with chronic pain, opioids may be used in those for whom NSAIDs present too great a risk, including those with diabetes, stomach or heart problems. They may also be useful for a select group of people with neuropathic pain.[101]

Surgery

Surgery may be useful in those with a herniated disc that is causing significant pain radiating into the leg, significant leg weakness, bladder problems, or loss of bowel control.[15] It may also be useful in those with spinal stenosis.[16] In the absence of these issues, there is no clear evidence of a benefit from surgery.[15]

For those with pain localized to the lower back due to disc degeneration, fair evidence supports

Alternative medicine

It is unclear if alternative treatments are useful for non-chronic back pain.

The evidence supporting acupuncture treatment for providing clinically beneficial acute and chronic pain relief is very weak.[114] When compared to a 'sham' treatment, no differences in pain relief or improvements in a person's quality of life were found.[114] There is very weak evidence that acupuncture may be better than no treatment at all for immediate relief.[114] A 2012 systematic review reported the findings that for people with chronic pain, acupuncture may improve pain a little more than no treatment and about the same as medications, but it does not help with disability.[115] This pain benefit is only present right after treatment and not at follow-up.[115] Acupuncture may be an option for those with chronic pain that does not respond to other treatments like conservative care and medications,[1][116] however this depends on patient preference, the cost, and on how accessible acupuncture is for the person.[114]

Prolotherapy – the practice of injecting solutions into joints (or other areas) to cause inflammation and thereby stimulate the body's healing response – has not been found to be effective by itself, although it may be helpful when added to another therapy.[19]

Herbal medicines, as a whole, are poorly supported by evidence.

Tentative evidence supports neuroreflexotherapy (NRT), in which small pieces of metal are placed just under the skin of the ear and back, for non-specific low back pain.[122][123][19] Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation (MBR), targeting physical and psychological aspects, may improve back pain but evidence is limited.[124] There is a lack of good quality evidence to support the use of radiofrequency denervation for pain relief.[125]

Education

There is strong evidence that education may improve low back pain, with a 2.5 hour educational session more effective than usual care for helping people return to work in the short- and long-term. This was more effective for people with acute rather than chronic back pain.[127] The benefit of training for preventing back pain in people who work manually with materials or is not clear, however moderate quality evidence does not show a role in preventing back pain.[128]

Prognosis

Overall, the outcome for acute low back pain is positive. Pain and disability usually improve a great deal in the first six weeks, with complete recovery reported by 40 to 90%.[2] In those who still have symptoms after six weeks, improvement is generally slower with only small gains up to one year. At one year, pain and disability levels are low to minimal in most people. Distress, previous low back pain, and job satisfaction are predictors of long-term outcome after an episode of acute pain.[2] Certain psychological problems such as depression, or unhappiness due to loss of employment may prolong the episode of low back pain.[17] Following a first episode of back pain, recurrences occur in more than half of people.[26]

For persistent low back pain, the short-term outcome is also positive, with improvement in the first six weeks but very little improvement after that. At one year, those with chronic low back pain usually continue to have moderate pain and disability.[2] People at higher risk of long-term disability include those with poor coping skills or with fear of activity (2.5 times more likely to have poor outcomes at one year),[129] those with a poor ability to cope with pain, functional impairments, poor general health, or a significant psychiatric or psychological component to the pain (Waddell's signs).[129]

Prognosis may be influenced by expectations, with those having positive expectations of recovery related to higher likelihood of returning to work and overall outcomes.[130]

Epidemiology

Low back pain that lasts at least one day and limits activity is a common complaint.[7] Globally, about 40% of people have low back pain at some point in their lives,[7] with estimates as high as 80% of people in the developed world.[25] Approximately 9 to 12% of people (632 million) have low back pain at any given point in time, which was calculated to 7460 per 100,000 globally in 2020.[24] Nearly one quarter (23.2%) report having it at some point over any one-month period.[7][8] Difficulty most often begins between 20 and 40 years of age.[1] However, low back pain becomes increasingly common with age, and is most common in the age group of 85.[24] Older adults more greatly affected by low back pain; they are more likely to lose mobility and independence and less likely to continue to participate in social and family activities.[24]

Women have higher rates of low back pain than men within all age groups, and this difference becomes more marked in older age groups (above 75 years).[24] In a 2012 review which found a higher rate in females than males, the reviewers thought this may be attributable to greater rates of pains due to osteoporosis, menstruation, and pregnancy among women, or possibly because women were more willing to report pain than men.[7] An estimated 70% of women experience back pain during pregnancy with the rate being higher the further along in pregnancy.[131]

Although the majority of low back pain has no specific underlying cause, workplace ergonomics, smoking and obesity are associated with low back pain in approximately 30% of cases.[24] Low levels of activity is also associated with low back pain.[54] Workplace ergonomics associated with low back pain include lifting, bending, vibration and physically demanding work, as well as prolonged sitting, standing and awkward postures.[24] Current smokers – and especially those who are adolescents – are more likely to have low back pain than former smokers, and former smokers are more likely to have low back pain than those who have never smoked.[132]

The overall number of individuals affected expected to increase with population growth and as the population ages,[24] with the largest increases expectedin low- and middle-income countries.[54]

History

Low back pain has been with humans since at least the

At the start of the 20th century, physicians thought low back pain was caused by inflammation of or damage to the nerves,

Emerging technologies such as X-rays gave physicians new diagnostic tools, revealing the intervertebral disc as a source for back pain in some cases. In 1938, orthopedic surgeon Joseph S. Barr reported on cases of disc-related sciatica improved or cured with back surgery.[134] As a result of this work, in the 1940s, the vertebral disc model of low back pain took over,[133] dominating the literature through the 1980s, aiding further by the rise of new imaging technologies such as CT and MRI.[134] The discussion subsided as research showed disc problems to be a relatively uncommon cause of the pain. Since then, physicians have come to realize that it is unlikely that a specific cause for low back pain can be identified in many cases and question the need to find one at all as most of the time symptoms resolve within 6 to 12 weeks regardless of treatment.[133]

Society and culture

Low back pain results in large economic costs. In the United States, it is the most common type of pain in adults, responsible for a large number of missed work days, and is the most common musculoskeletal complaint seen in the emergency department.[28] In 1998, it was estimated to be responsible for $90 billion in annual health care costs, with 5% of individuals incurring most (75%) of the costs.[28] Between 1990 and 2001 there was a more than twofold increase in spinal fusion surgeries in the US, despite the fact that there were no changes to the indications for surgery or new evidence of greater usefulness.[10] Further costs occur in the form of lost income and productivity, with low back pain responsible for 40% of all missed work days in the United States.[135] Low back pain causes disability in a larger percentage of the workforce in Canada, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Sweden than in the US or Germany.[135] In the United States, low back pain is highest of Years Lived With Disability (YLDs) rank, rate, and rercentage Change for the 25 leading causes of disability and injury, between 1990 and 2016.[136]

Workers who experience acute low back pain as a result of a work injury may be asked by their employers to have x-rays.[137] As in other cases, testing is not indicated unless red flags are present.[137] An employer's concern about legal liability is not a medical indication and should not be used to justify medical testing when it is not indicated.[137] There should be no legal reason for encouraging people to have tests which a health care provider determines are not indicated.[137]

Research

References

- ^ PMID 22335313.

- ^ PMID 22586331.

- ^ PMID 20602122.

- ^ a b c d "Low Back Pain Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ PMID 22958556.

- ^ PMID 28192789.

- ^ PMID 22231424.

- ^ PMID 23245607.

- ^ American Academy of Family Physicians, Choosing Wisely (2023). "Imaging for Low Back Pain". www.aafp.org. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ PMID 19124635.

- ^ PMID 22958558.

- PMID 38470617.

- ^ PMID 36327391.

- ^ PMID 25561513.

- ^ PMID 22958562.

- ^ S2CID 1504909.

- ^ PMID 22958559.

- ^ PMID 20614428.

- ^ PMID 22958563.

- S2CID 26310171.

- PMID 20869008.

- ^ PMID 21328304.

- PMID 22972127.

- ^ PMID 37273833.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-0265-9. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 19921522.

- S2CID 19569862.

- ^ from the original on 14 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Low Back Pain Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- S2CID 201756091.

- ^ "Fast Facts About Back Pain". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. National Institute of Health. September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Low back pain – acute". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- PMID 21365902.

- PMID 21782073.

- ^ Floyd, R., & Thompson, Clem. (2008). Manual of structural kinesiology. New York: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages. [ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ S2CID 22246810.

- ^ PMID 23015552. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Patel NB (2010). "Chapter 3: Physiology of Pain". In Kopf A, Patel NB (eds.). Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ S2CID 78716905.

- ^ Davis PC, Wippold II FJ, Cornelius RS, et al. (2011). American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria – Low Back Pain (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2012.

- ABIM Foundation, North American Spine Society, retrieved 25 March 2013, which cites

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekelle P, Owens DK, et al. (Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel) (October 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (7): 478–491. PMID 17909209.

- Forseen SE, Corey AS (October 2012). "Clinical decision support and acute low back pain: evidence-based order sets". Journal of the American College of Radiology. 9 (10): 704–712.e4. PMID 23025864.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekelle P, Owens DK, et al. (Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel) (October 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (7): 478–491.

- ^ PMID 38014846.

- PMID 23450586.

- ^ PMID 24335669.

- PMID 19461822.

- ^ a b c d "Use of imaging studies for low back pain: percentage of members with a primary diagnosis of low back pain who did not have an imaging study (plain x-ray, MRI, CT scan) within 28 days of the diagnosis". 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Family Physicians, archivedfrom the original on 10 February 2013, retrieved 5 September 2012

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American College of Physicians, archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 5 September 2013

- S2CID 31602395.

- PMID 23547591.

- ^ S2CID 1326352.

- S2CID 207399397.

- ^ PMID 26752509.

- ^ S2CID 4354991.

- ^ PMID 20091596.

- PMID 17909209.

- ^ PMID 31977923.

- ^ S2CID 22162952.

- PMID 38470617.

- PMID 22958557.

- PMID 23026978.

- PMID 27707631.

- PMID 34580864.

- S2CID 205989057.

- PMID 21053026.

- PMID 23990391.

- PMID 20414688.

- PMID 16437495.

- ^ PMID 20640863.

- PMID 22958560.

- PMID 32623724.

- OCLC 1198756858.

- PMID 26985522.

- PMID 18425875.

- ^ PMID 34580864.

- PMID 20438611.

- PMID 20227641.

- S2CID 47013227.

- S2CID 7579458.

- S2CID 17095187.

- S2CID 253627174.

- PMID 26742533.

- PMID 32503243.

- ^ PMID 26133923.

- PMID 25180773.

- PMID 23114579.

- PMID 20042705.

- ^ "Acute low back pain without radiculopathy". English.prescrire.org. October 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ S2CID 22850331.

- PMID 32297973.

- PMID 27271789.

- PMID 25828856.

- PMID 26863524.

- PMID 23726390.

- PMID 36269125.

- PMID 25267983.

- S2CID 25356400.

- PMID 26987082.

- PMID 27438382.

- S2CID 29903177.

- PMID 23414718.

- PMID 29970367.

- S2CID 10658374.

- S2CID 21203011.

- ^ "Epidural Corticosteroid Injection: Drug Safety Communication – Risk of Rare But Serious Neurologic Problems". FDA. 23 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- PMID 22972118.

- PMID 21369477.

- PMID 36878313.

- S2CID 34520820.

- PMID 30867144.

- PMID 22972127.

- PMID 18164462.

- PMID 26863390.

- ^ PMID 33306198.

- ^ PMID 22203884.

- PMID 21229367.

- ^ PMID 26329399.

- S2CID 42119774.

- S2CID 3680364.

- PMID 23009599.

- S2CID 1157568.

- PMID 15106186.

- S2CID 31140257.

- PMID 28656659.

- PMID 26495910.

- S2CID 49486200.

- PMID 18254037.

- PMID 21678349.

- ^ PMID 20371789.

- PMID 31765487.

- ISBN 978-0-07-170285-0. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- PMID 20102998.

- ^ PMID 22958555.

- ^ S2CID 25083375.

- ^ PMID 19668291.

- PMID 29634829.

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2014, retrieved 24 February 2014, which cites

- Talmage J, Belcourt R, Galper J, et al. (2011). "Low back disorders". In Hegmann KT (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. pp. 336, 373, 376–77. ISBN 978-0-615-45227-2.

- Talmage J, Belcourt R, Galper J, et al. (2011). "Low back disorders". In Hegmann KT (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. pp. 336, 373, 376–77.

External links

- Back and spine at Curlie

- Back Pain at MedlinePlus.gov