Ctenophora

| Comb jellies Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| "Ctenophorae" (comb jelly) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Ctenophora Eschscholtz, 1829 |

| Classes | |

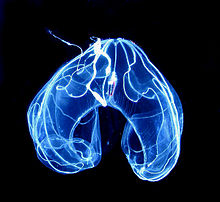

Ctenophora (

Depending on the species, adult ctenophores range from a few

Their bodies consist of a mass of jelly, with a layer two cells thick on the outside, and another lining the internal cavity. The phylum has a wide range of body forms, including the egg-shaped cydippids with a pair of retractable tentacles that capture prey, the flat generally combless platyctenids, and the large-mouthed beroids, which prey on other ctenophores.

Almost all ctenophores function as

Despite their soft, gelatinous bodies, fossils thought to represent ctenophores appear in

Distinguishing features

Among animal phyla, the Ctenophores are more complex than sponges, about as complex as cnidarians (jellyfish, sea anemones, etc.), and less complex than bilaterians (which include almost all other animals). Unlike sponges, both ctenophores and cnidarians have:

- cells bound by inter-cell connections and

- carpet-like basement membranes;

- muscles;

- nervous systems; and

- sensoryorgans (in some, not all).

Ctenophores are distinguished from all other animals by having colloblasts, which are sticky and adhere to prey, although a few ctenophore species lack them.[18][19]

Like cnidarians, ctenophores have two main layers of cells that sandwich a middle layer of jelly-like material, which is called the

Both ctenophores and cnidarians have a type of muscle that, in more complex animals, arises from the middle cell layer,[21] and as a result some recent text books classify ctenophores asRanging from about 1 millimeter (0.04 in) to 1.5 meters (5 ft) in size,[22][24] ctenophores are the largest non-colonial animals that use

| Ctenophores[18][22] | Bilateria[18] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cnidocytes | No | Yes | Only in some species (obtained from ingested cnidarians) | |

| microRNA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hox genes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Colloblasts | No | In most species[19] | No | |

organs

|

No | Yes | ||

| Anal pores | No | Yes | Only in some flatworms | |

| Number of main cell layers | Two, with jelly-like layer between them | Debate about whether two[18] or three[21][22] | Three | |

| Cells in each layer bound together | No, except that Homoscleromorpha have basement membranes[29]

|

Yes: Inter-cell connections; basement membranes | ||

Sensory organs

|

No | Yes | ||

| Eyes (e.g. ocelli )

|

No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Apical organ | No | Yes | Yes | In species with primary ciliated larvae |

| Cell abundance in middle "jelly" layer |

Many | Few | [not applicable] | |

| Outer layer cells can move inwards and change functions |

Yes | No | ||

| Nervous system | No | Yes, simple | Simple to complex | |

| Muscles | None | Mostly epitheliomuscular | Mostly myoepithelial

|

Mostly myocytes

|

Description

For a phylum with relatively few species, ctenophores have a wide range of body plans.[22] Coastal species need to be tough enough to withstand waves and swirling sediment particles, while some oceanic species are so fragile that it is very difficult to capture them intact for study.[19] In addition, oceanic species do not preserve well,[19] and are known mainly from photographs and from observers' notes.[30] Hence most attention has until recently concentrated on three coastal genera – Pleurobrachia, Beroe and Mnemiopsis.[19][31] At least two textbooks base their descriptions of ctenophores on the cydippid Pleurobrachia.[18][22]

Since the body of many species is almost

Common features

The Ctenophore

Body layers

Like those of

The outer layer of the epidermis (outer skin) consists of: sensory cells; cells that secrete mucus, which protects the body; and interstitial cells, which can transform into other types of cell. In specialized parts of the body, the outer layer also contains colloblasts, found along the surface of tentacles and used in capturing prey, or cells bearing multiple large cilia, for locomotion. The inner layer of the epidermis contains a nerve net, and myoepithelial cells that act as muscles.[22]

The internal cavity forms: a mouth that can usually be closed by muscles; a

Feeding, excretion and respiration

When prey is swallowed, it is liquefied in the

Little is known about how ctenophores get rid of waste products produced by the cells. The ciliary rosettes in the gastrodermis may help to remove wastes from the mesoglea, and may also help to adjust the animal's buoyancy by pumping water into or out of the mesoglea.[22]

Locomotion

The outer surface bears usually eight comb rows, called swimming-plates, which are used for swimming. The rows are oriented to run from near the mouth (the "oral pole") to the opposite end (the "aboral pole"), and are spaced more or less evenly around the body,[18] although spacing patterns vary by species and in most species the comb rows extend only part of the distance from the aboral pole towards the mouth. The "combs" (also called "ctenes" or "comb plates") run across each row, and each consists of thousands of unusually long cilia, up to 2 millimeters (0.08 in). Unlike conventional cilia and flagella, which has a filament structure arranged in a 9 + 2 pattern, these cilia are arranged in a 9 + 3 pattern, where the extra compact filament is suspected to have a supporting function.[33] These normally beat so that the propulsion stroke is away from the mouth, although they can also reverse direction. Hence ctenophores usually swim in the direction in which the mouth is eating, unlike jellyfish.[22] When trying to escape predators, one species can accelerate to six times its normal speed;[34] some other species reverse direction as part of their escape behavior, by reversing the power stroke of the comb plate cilia.

It is uncertain how ctenophores control their buoyancy, but experiments have shown that some species rely on osmotic pressure to adapt to the water of different densities.[35] Their body fluids are normally as concentrated as seawater. If they enter less dense brackish water, the ciliary rosettes in the body cavity may pump this into the mesoglea to increase its bulk and decrease its density, to avoid sinking. Conversely, if they move from brackish to full-strength seawater, the rosettes may pump water out of the mesoglea to reduce its volume and increase its density.[22]

Nervous system and senses

Ctenophores have no

In addition there is a less organized mesogleal nerve net consisting of single neurites. The largest single sensory feature is the

Research supports the hypothesis that the ciliated larvae in cnidarians and bilaterians share an ancient and common origin.[42] The larvae's apical organ is involved in the formation of the nervous system.[43] The aboral organ of comb jellies is not homologous with the apical organ in other animals, and the formation of their nervous system has therefore a different embryonic origin.[44]

Ctenophore nerve cells and nervous system have different biochemistry as compared to other animals. For instance, they lack the genes and enzymes required to manufacture neurotransmitters like

Cydippids

Cydippid ctenophores have bodies that are more or less rounded, sometimes nearly spherical and other times more cylindrical or egg-shaped; the common coastal "sea gooseberry", Pleurobrachia, sometimes has an egg-shaped body with the mouth at the narrow end,[22] although some individuals are more uniformly round. From opposite sides of the body extends a pair of long, slender tentacles, each housed in a sheath into which it can be withdrawn.[18] Some species of cydippids have bodies that are flattened to various extents so that they are wider in the plane of the tentacles.[22]

The tentacles of cydippid ctenophores are typically fringed with tentilla ("little tentacles"), although a few genera have simple tentacles without these side branches. The tentacles and tentilla are densely covered with microscopic

In addition to colloblasts, members of the genus

There are eight rows of combs that run from near the mouth to the opposite end, and are spaced evenly round the body.

Lobates

The Lobata has a pair of lobes, which are muscular, cuplike extensions of the body that project beyond the mouth. Their inconspicuous tentacles originate from the corners of the mouth, running in convoluted grooves and spreading out over the inner surface of the lobes (rather than trailing far behind, as in the Cydippida). Between the lobes on either side of the mouth, many species of lobates have four auricles, gelatinous projections edged with cilia that produce water currents that help direct microscopic prey toward the mouth. This combination of structures enables lobates to feed continuously on suspended planktonic prey.[22]

Lobates have eight comb-rows, originating at the aboral pole and usually not extending beyond the body to the lobes; in species with (four) auricles, the cilia edging the auricles are extensions of cilia in four of the comb rows. Most lobates are quite passive when moving through the water, using the cilia on their comb rows for propulsion,

An unusual species first described in 2000, Lobatolampea tetragona, has been classified as a lobate, although the lobes are "primitive" and the body is

Beroids

The

Other body forms

The

The

The

Most Platyctenida have oval bodies that are flattened in the oral-aboral direction, with a pair of tentilla-bearing tentacles on the aboral surface. They cling to and creep on surfaces by everting the pharynx and using it as a muscular "foot". All but one of the known platyctenid species lack comb-rows.[22] Platyctenids are usually cryptically colored, live on rocks, algae, or the body surfaces of other invertebrates, and are often revealed by their long tentacles with many side branches, seen streaming off the back of the ctenophore into the current.

Reproduction and development

Adults of most species can regenerate tissues that are damaged or removed,[61] although only platyctenids reproduce by cloning, splitting off from the edges of their flat bodies fragments that develop into new individuals.[22]

The last common ancestor (LCA) of the ctenophores was hermaphroditic.[62] Some are simultaneous hermaphrodites, which can produce both eggs and sperm at the same time, while others are sequential hermaphrodites, in which the eggs and sperm mature at different times. There is no metamorphosis.[63] At least three species are known to have evolved separate sexes (dioecy); Ocyropsis crystallina and Ocyropsis maculata in the genus Ocyropsis and Bathocyroe fosteri in the genus Bathocyroe.[64] The gonads are located in the parts of the internal canal network under the comb rows, and eggs and sperm are released via pores in the epidermis. Fertilization is generally external, but platyctenids use internal fertilization and keep the eggs in brood chambers until they hatch. Self-fertilization has occasionally been seen in species of the genus Mnemiopsis,[22] and it is thought that most of the hermaphroditic species are self-fertile.[19]

Development of the fertilized eggs is direct; there is no distinctive larval form. Juveniles of all groups are generally planktonic, and most species resemble miniature adult cydippids, gradually developing their adult body forms as they grow. In the genus Beroe, however, the juveniles have large mouths and, like the adults, lack both tentacles and tentacle sheaths. In some groups, such as the flat, bottom-dwelling platyctenids, the juveniles behave more like true larvae. They live among the plankton and thus occupy a different ecological niche from their parents, only attaining the adult form by a more radical ontogeny.[22] after dropping to the sea-floor.[19]

At least in some species, juvenile ctenophores appear capable of producing small quantities of eggs and sperm while they are well below adult size, and adults produce eggs and sperm for as long as they have sufficient food. If they run short of food, they first stop producing eggs and sperm, and then shrink in size. When the food supply improves, they grow back to normal size and then resume reproduction. These features make ctenophores capable of increasing their populations very quickly.[19] Members of the Lobata and Cydippida also have a reproduction form called dissogeny; two sexually mature stages, first as larva and later as juveniles and adults. During their time as larva they are capable of releasing gametes periodically. After their first reproductive period is over they will not produce more gametes again until later. A population of Mertensia ovum in the central Baltic Sea have become paedogenetic, and consist solely of sexually mature larvae less than 1.6 mm.[65][66]

In Mnemiopsis leidyi, nitric oxide (NO) signaling is present both in adult tissues and differentially expressed in later embryonic stages suggesting the involvement of NO in developmental mechanisms.[67]

Colors and bioluminescence

Most ctenophores that live near the surface are mostly colorless and almost transparent. However some deeper-living species are strongly pigmented, for example the species known as "Tortugas red"[68] (see illustration here), which has not yet been formally described.[19] Platyctenids generally live attached to other sea-bottom organisms, and often have similar colors to these host organisms.[19] The gut of the deep-sea genus Bathocyroe is red, which hides the bioluminescence of copepods it has swallowed.[56]

The comb rows of most planktonic ctenophores produce a rainbow effect, which is not caused by bioluminescence but by the scattering of light as the combs move.[19][69] Most species are also bioluminescent, but the light is usually blue or green and can only be seen in darkness.[19] However some significant groups, including all known platyctenids and the cydippid genus Pleurobrachia, are incapable of bioluminescence.[70]

When some species, including Bathyctena chuni, Euplokamis stationis and Eurhamphaea vexilligera, are disturbed, they produce secretions (ink) that luminesce at much the same wavelengths as their bodies. Juveniles will luminesce more brightly in relation to their body size than adults, whose luminescence is diffused over their bodies. Detailed statistical investigation has not suggested the function of ctenophores' bioluminescence nor produced any correlation between its exact color and any aspect of the animals' environments, such as depth or whether they live in coastal or mid-ocean waters.[71]

In ctenophores, bioluminescence is caused by the activation of calcium-activated proteins named

Ecology

Distribution

Ctenophores are found in most marine environments: from polar waters at −2°C to the tropics at 30°C; near coasts and in mid-ocean; from the surface waters to the ocean depths at more than 7000 meters.[73] The best-understood are the genera Pleurobrachia, Beroe and Mnemiopsis, as these planktonic coastal forms are among the most likely to be collected near shore.[31][56] No ctenophores have been found in fresh water.

In 2013 Mnemiopsis was recorded in lake Birket Qarun, and in 2014 in lake El Rayan II, both near Faiyum in Egypt, where they were accidentally introduced by the transport of fish (mullet) fry. Though many species prefer brackish waters like estuaries and coastal lagoons in open connection with the sea, this was the first record from an inland environment. Both lakes are saline, with Birket Qarun being hypersaline, and shows that some ctenophores can establish themselves in saline limnic environments without connection to the ocean. In the long run it is not expected the populations will survive. The two limiting factors in saline lakes are availability of food and a varied diet, and high temperatures during hot summers. Because a parasitic isopod, Livoneca redmanii, was introduced at the same time, it is difficult to say how much of the ecological impact of invasive species is caused by the ctenophore alone.[74][75][76]

Ctenophores may be abundant during the summer months in some coastal locations, but in other places, they are uncommon and difficult to find.

In bays where they occur in very high numbers, predation by ctenophores may control the populations of small zooplanktonic organisms such as copepods, which might otherwise wipe out the phytoplankton (planktonic plants), which are a vital part of marine food chains.

Prey and predators

Almost all ctenophores are

Ctenophores used to be regarded as "dead ends" in marine food chains because it was thought their low ratio of organic matter to salt and water made them a poor diet for other animals. It is also often difficult to identify the remains of ctenophores in the guts of possible predators, although the combs sometimes remain intact long enough to provide a clue. Detailed investigation of chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta, showed that these fish digest ctenophores 20 times as fast as an equal weight of shrimps, and that ctenophores can provide a good diet if there are enough of them around. Beroids prey mainly on other ctenophores. Some jellyfish and turtles eat large quantities of ctenophores, and jellyfish may temporarily wipe out ctenophore populations. Since ctenophores and jellyfish often have large seasonal variations in population, most fish that prey on them are generalists and may have a greater effect on populations than the specialist jelly-eaters. This is underlined by an observation of herbivorous fishes deliberately feeding on gelatinous zooplankton during blooms in the Red Sea.[79] The larvae of some sea anemones are parasites on ctenophores, as are the larvae of some flatworms that parasitize fish when they reach adulthood.[80]

Ecological impacts

Most species are

Ctenophores may balance marine ecosystems by preventing an over-abundance of copepods from eating all the phytoplankton (planktonic plants),[81] which are the dominant marine producers of organic matter from non-organic ingredients.[82]

On the other hand, in the late 1980s the Western Atlantic ctenophore

In the late 1990s Mnemiopsis appeared in the

Taxonomy

The number of known living ctenophore species is uncertain since many of those named and formally described have turned out to be identical to species known under other scientific names. Claudia Mills estimates that there about 100 to 150 valid species that are not duplicates, and that at least another 25, mostly deep-sea forms, have been recognized as distinct but not yet analyzed in enough detail to support a formal description and naming.[68]

Early classification

Early writers combined ctenophores with

Modern taxonomy

The traditional classification divides ctenophores into two

The Tentaculata are divided into the following eight orders:[68]

- Cydippida, egg-shaped animals with long tentacles[22]

- Lobata, with paired thick lobes[22]

- Platyctenida, flattened animals that live on or near the sea-bed; most lack combs as adults, and use their pharynges as suckers to attach themselves to surfaces[22]

- Cambojiida

- Cryptolobiferida

- Thalassocalycida, with short tentacles and a jellyfish-like "umbrella"[22]

- Cestida, ribbon-shaped and the largest ctenophores[22]

Evolutionary history

Despite their fragile, gelatinous bodies, fossils thought to represent ctenophores – apparently with no tentacles but many more comb-rows than modern forms – have been found in Lagerstätten as far back as the early Cambrian, about 515 million years ago. Nevertheless, a recent molecular phylogenetics analysis concludes that the common ancestor originated approximately 350 million years ago ± 88 million years ago, conflicting with previous estimates which suggests it occurred 66 million years ago after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.[88]

Fossil record

Because of their soft, gelatinous bodies, ctenophores are extremely rare as fossils, and fossils that have been interpreted as ctenophores have been found only in

The Ediacaran Eoandromeda could putatively represent a comb jelly.[2] It has eightfold symmetry, with eight spiral arms resembling the comblike rows of a ctenophore. If it is indeed ctenophore, it places the group close to the origin of the Bilateria.[91] The early Cambrian

520 million years old Cambrian fossils also from Chengjiang in China show a now wholly extinct class of ctenophore, named "Scleroctenophora", that had a complex internal skeleton with long spines.[95] The skeleton also supported eight soft-bodied flaps, which could have been used for swimming and possibly feeding. One form, Thaumactena, had a streamlined body resembling that of arrow worms and could have been an agile swimmer.[5]

Relationship to other animal groups

The

A series of studies that looked at the presence and absence of members of gene families and signalling pathways (e.g.,

Other researchers have argued that the placement of Ctenophora as sister to all other animals is a statistical anomaly caused by the high rate of evolution in ctenophore genomes, and that

Yet another study strongly rejects the hypothesis that sponges are the sister group to all other extant animals and establishes the placement of Ctenophora as the sister group to all other animals, and disagreement with the last-mentioned paper is explained by methodological problems in analyses in that work.[13] Neither ctenophores or

Relationships within Ctenophora

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since all modern ctenophores except the beroids have cydippid-like larvae, it has widely been assumed that their last common ancestor also resembled cydippids, having an egg-shaped body and a pair of retractable tentacles. Richard Harbison's purely morphological analysis in 1985 concluded that the cydippids are not monophyletic, in other words do not contain all and only the descendants of a single common ancestor that was itself a cydippid. Instead he found that various cydippid families were more similar to members of other ctenophore orders than to other cydippids. He also suggested that the last common ancestor of modern ctenophores was either cydippid-like or beroid-like.[128] A molecular phylogeny analysis in 2001, using 26 species, including 4 recently discovered ones, confirmed that the cydippids are not monophyletic and concluded that the last common ancestor of modern ctenophores was cydippid-like. It also found that the genetic differences between these species were very small – so small that the relationships between the Lobata, Cestida and Thalassocalycida remained uncertain. This suggests that the last common ancestor of modern ctenophores was relatively recent, and perhaps survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65.5 million years ago while other lineages perished. When the analysis was broadened to include representatives of other phyla, it concluded that cnidarians are probably more closely related to bilaterians than either group is to ctenophores but that this diagnosis is uncertain.[127] A clade including Mertensia, Charistephane and Euplokamis may be the sister lineage to all other ctenophores.[129][13]

Divergence times estimated from molecular data indicated approximately how many million years ago (Mya) the major clades diversified: 350 Mya for Cydippida relative to other Ctenophora, and 260 Mya for Platyctenida relative to Beroida and Lobata.[13]

See also

References

- PMID 17404242.

- ^ S2CID 28369431.

- S2CID 4259485.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 26601209.

- ^ Fowler, George Herbert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 593.

- ^ WoRMS Editorial Board (2024), World Register of Marine Species. Accessed 2019-09-18., VLIZ, retrieved 19 February 2024

- ^ PMID 28318975.

- ^ S2CID 4397099.

- PMID 24337300.

- PMID 26621703.

- ^ Berwald, Juli (2017). Spineless: the science of jellyfish and the art of growing a backbone. Riverhead Books.[page needed]

- ^ PMID 28993654.

- PMID 26862177.

- S2CID 4447056.

- PMID 37198475.

- ^

Ryan, Joseph F.; Schnitzler, Christine E.; Tamm, Sidney L. (December 2016). "Meeting report of Ctenopalooza: The first international meeting of ctenophorologists". EvoDevo. 7 (1): 19. S2CID 931968.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l

Hinde, R.T. (1998). "The Cnidaria and Ctenophor". In Anderson, D.T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–57. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mills, C.E. "Ctenophores – some notes from an expert". University of Washington. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ a b

Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 111–124. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b

Seipel, K.; Schmid, V. (June 2005). "Evolution of striated muscle: Jellyfish and the origin of triploblasty". Developmental Biology. 282 (1): 14–26. PMID 15936326.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj

Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 182–195. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^

Moroz, Leonid L.; Norekian, Tigran P. (16 August 2018). "Atlas of Neuromuscular Organization in the Ctenophore, Pleurobrachia bachei (A. Agassiz, 1860)". bioRxiv 10.1101/385435.

- ^ Viitasalo, S.; Lehtiniemi, M. & Katajisto, T. (2008). "The invasive ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi overwinters in high abundances in the subarctic Baltic Sea". Journal of Plankton Research. 30 (12): 1431–1436. .

- ^ Trumble, W.; Brown, L. (2002). "Ctenophore". Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ^

Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 76–97. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^

Bergquist, P.R. (1998). "Porifera". In Anderson, D.T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–27. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ a b c

Moroz, Leonid L.; Kocot, Kevin M.; Citarella, Mathew R.; Dosung, Sohn; Norekian, Tigran P.; Povolotskaya, Inna S.; et al. (June 2014). "The ctenophore genome and the evolutionary origins of neural systems". Nature. 510 (7503): 109–114. PMID 24847885.

- ^

Exposito, J-Y.; Cluzel, C.; Garrone, R. & Lethias, C. (2002). "Evolution of collagens". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 268 (3): 302–316. S2CID 12376172.

- ^ a b Horita, T. (March 2000). "An undescribed lobate ctenophore, Lobatolampea tetragona gen. nov. & spec. nov., representing a new family, from Japan". Zoologische Mededelingen. 73 (30): 457–464. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ S2CID 17105070.

- PMID 10525332.

- PMID 13681575.

- S2CID 32975367.

- JSTOR 1541442.

- ^ Alien-like comb jellies have a nervous system like nothing ever seen before

- ^ The jellyfish with a nervous system that is causing a shiver in the scientific community

- ^ S2CID 258239574. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- PMID 34522849.

- S2CID 92852830.

- ^ Did the ctenophore nervous system evolve independently?

- PMID 24476105.

- S2CID 3151957.

- PMID 31417759.

- Aeon. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- S2CID 256811787.

- PMID 30632608.

- ISBN 9780199682201.

- PMID 25905000.

- ^ Five types of colloblast in a cydippid ctenophore, Minictena luteola Carré and Carré: an ultrastructural study and cytological interpretation

- ^ Characterizing functional biodiversity across the phylum Ctenophora using physiological measurements

- S2CID 17714037.

- S2CID 317017.

- ^ S2CID 24584197.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 21669763.

- PMID 3914479.

- PMID 29304670.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-930118-23-5.

- PMID 2878844.

- PMID 29207942.

- PMID 35476523.

- S2CID 83954780.

- PMID 27489613.

- PMID 22535640.

- PMID 37034176.

- ^ a b c d Mills, C. E. (May 2007). "Phylum Ctenophora: list of all valid scientific names". Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- PMID 16711845.

- PMID 29244577.

- S2CID 14523078.

- PMID 23259493.

- ^ Depth- and temperature-specific fatty acid adaptations in ctenophores from extreme habitats

- .

- ^ First record of a ctenophore in lakes: the comb-jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi A. Agassiz, 1865 invades the Fayum, Egypt

- ^ Molecular and morphological confirmation of an invasive American isopod; Livoneca redmanii Leach, 1818, from the Mediterranean region to Lake Qaroun, Egypt

- .

- PMID 28570175.

- S2CID 24694789.

- S2CID 86663092.

- ^ .

- PMID 9657713.

- ^ S2CID 23336715.

- ^ .

- )

- ISBN 978-1-4020-1866-4.

- ^ "Comb Jelly Neurons Spark Evolution Debate". Quanta Magazine. 2015-03-25. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- PMID 28993654.

- PMID 14756326. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-12-24. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- PMID 34561497.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (7 September 2011). "Ancient Sea Jelly Shakes Evolutionary Tree of Animals". Scientific American. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- S2CID 1235914.

- .

- ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Mindy, Weisberger (2015-07-10). "Ancient Jellies Had Spiny Skeletons, No Tentacles". livescience.com.

- ISBN 978-0-521-11158-4.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-245-56027-6.

- ISBN 978-1-120-86850-3.

- ISBN 978-0-07-031660-7.

- S2CID 15282843.

- S2CID 86185156.

- S2CID 11108911.

- ^ PMID 20378579.

- PMID 19759036.

- PMID 20920347.

- PMID 21291545.

- PMID 20920349.

- PMID 21576472.

- ^ PMID 24337300.

- PMID 25902535.

- PMID 26596625.

- S2CID 15282843.

- PMID 23353073.

- PMID 26621703.

- PMID 33310849.

- PMID 34224654.

- PMID 22201557.

- PMID 30002868.

- ^ Into the Brain of Comb Jellies: Scientists Explore the Evolution of Neurons

- PMID 29402379.

- ^ Conserved biophysical features of the CaV2 presynaptic Ca2+ channel homologue from the early-diverging animal Trichoplax adhaerens

- ^ Evolution and Development - page 38 Archived 2014-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 25888821.

- S2CID 208578827.

- ^ Independent Innexin Radiation Shaped Signaling in Ctenophores

- ^ PMID 11697917.

- ISBN 978-0-19-857181-0.

- PMID 25440713.

Further reading

- R. S. K. Barnes, P. Calow, P. J. W. Olive, D. W. Golding, J. I. Spicer, The invertebrates – a synthesis, 3rd ed, Blackwell, 2001, ch. 3.4.3, p. 63, ISBN 0-632-04761-5

- R. C. Brusca, G. J. Brusca, Invertebrates, 2nd Ed, Sinauer Associates, 2003, ch. 9, p. 269, ISBN 0-87893-097-3

- J. Moore, An Introduction to the Invertebrates, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001, ch. 5.4, p. 65, ISBN 0-521-77914-6

- W. Schäfer, Ctenophora, Rippenquallen, in W. Westheide and R. Rieger: Spezielle Zoologie Band 1, Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1996

- Bruno Wenzel, Glastiere des Meeres. Rippenquallen (Acnidaria), 1958, ISBN 3-7403-0189-9

- Mark Shasha, Night of the Moonjellies, 1992, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-77565-0

- Douglas Fox, "Aliens in our midst: What the ctenophore says about the evolution of intelligence", 2017, Aeon.co.

External links

- Plankton Chronicles Short documentary films & photos

- Jellyfish and Comb Jellies overview at the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Ctenophores from the São Sebastião Channel, Brazil

- Video of ctenophores at the National Zoo in Washington DC

- Tree Of Animal Life Has Branches Rearranged, By Evolutionary Biologists

- Australian Ctenophora Fact Sheet

- The Jelly Connection – striking images, including a Beroe specimen attacking another ctenophore

- In Search of the First Animals