Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World | |

| |

| Founded | June 27, 1905[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Location |

|

Members | |

Key people | § Notable members |

| Publication | Industrial Worker |

| Website | iww |

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international

In the 1910s and early 1920s, the IWW achieved many of its short-term goals, particularly in the American West, and cut across traditional guild and union lines to organize workers in a variety of trades and industries. At their peak in August 1917, IWW membership was estimated at more than 150,000, with active wings in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

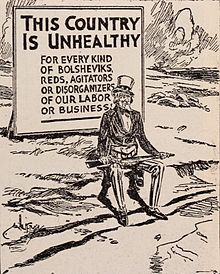

Membership declined dramatically in the late 1910s and 1920s. There were conflicts with other labor groups, particularly the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which regarded the IWW as too radical, while the IWW regarded the AFL as too conservative and opposed their decision to divide workers on the basis of their trades.[9] Membership also declined due to government crackdowns on radical, anarchist, and socialist groups during the First Red Scare after World War I. In Canada, the IWW was outlawed by the federal government by an Order in Council on September 24, 1918.[10]

Likely the most decisive factor in the decline in IWW membership and influence was a

The IWW promotes the concept of "

United States

1905–1950

Foundation

The first meeting to plan the IWW was held in Chicago in 1904. The seven attendees were Clarence Smith and

The

The convention had taken place on June 27, 1905, and was referred to as the "Industrial Congress" or the "Industrial Union Convention". It was later known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW.[8]: 67

The IWW's founders included

The IWW aimed to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class; its

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a

strugglemust go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth.We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

Instead of the conservative motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work," we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, "Abolition of the wage system."

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the

new society within the shell of the old.[14]

The Wobblies, as they were informally known, differed from other union movements of the time by promotion of industrial unionism, as opposed to the craft unionism of the AFL. The IWW emphasized rank-and-file organization, as opposed to empowering leaders who bargain with employers on behalf of workers. The early IWW chapters consistently refused to sign contracts, which they believed would restrict workers' abilities to aid each other when called upon. Though never developed in any detail, Wobblies envisioned the general strike as the means by which the wage system could be overthrown and a new economic system ushered in, one which emphasized people over profit, cooperation over competition.

One of the IWW's most important contributions to the labor movement and broader push of social justice was that, when founded, it was the only American union to welcome all workers, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians, into the same organization. Many of its early members were immigrants, and some, such as

Divide on political action or direct action

In 1908, a group led by

Organization

The few own the many because they possess the means of livelihood of all ... The country is governed for the richest, for the corporations, the bankers, the land speculators, and for the exploiters of labor. The majority of mankind are working people. So long as their fair demands – the ownership and control of their livelihoods – are set at naught, we can have neither men's rights nor women's rights. The majority of mankind is ground down by industrial oppression in order that the small remnant may live in ease.

— Helen Keller, IWW member, 1911[22]

The IWW first attracted attention in

By 1912, the organization had around 25,000 members,

Geography

In its first decades, the IWW created more than 900 unions located in more than 350 cities and towns in 38 states and territories of the United States and five Canadian provinces. and more.

IWW versus AFL Carpenters, Goldfield, Nevada, 1906-1907

The IWW assumed a prominent role in 1906 and 1907 in the gold-mining boom town of Goldfield, Nevada. At that time, the Western Federation of Miners was still an affiliate of the IWW (the WFM withdrew from the IWW in the summer of 1907). In 1906, the IWW became so powerful in Goldfield that it could dictate wages and working conditions.

Resisting IWW domination was the AFL-affiliated Carpenters Union. In March 1907, the IWW demanded that the mines deny employment to AFL Carpenters, which led mine owners to challenge the IWW. The mine owners banded together and pledged not to employ any IWW members. The mine and business owners of Goldfield staged a lockout, vowing to remain shut until they had broken the power of the IWW. The lockout prompted a split within the Goldfield workforce, between conservative and radical union members.[34]

The mine owners persuaded the Nevada governor to ask for federal troops. Under the protection of federal troops, the mine owners reopened the mines with non-union labor, breaking the influence of the IWW in Goldfield.

Haywood trial and Western Federation of Miners exit

Leaders of the Western Federation of Miners such as Bill Haywood and Vincent St. John were instrumental in forming the IWW, and the WFM affiliated with the new union organization shortly after the IWW was formed. The WFM became the IWW's "mining section". Many in the rank and file of the WFM were uncomfortable with the open radicalism of the IWW and wanted the WFM to maintain its independence. Schisms between the WFM and IWW had emerged at the annual IWW convention in 1906, when a majority of WFM delegates walked out.[8]

When WFM executives Bill Haywood, George Pettibone, and Charles Moyer were accused of complicity in the murder of former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg, the IWW used the case to raise funds and support and paid for the legal defense. Even the not guilty verdicts worked against the IWW, because the IWW was deprived of martyrs, and at the same time, a large portion of the public remained convinced of the guilt of the accused.[35] The trials caused a bitter split between Haywood and Moyer. The Haywood trial also provoked a reaction within the WFM against violence and radicalism. In the summer of 1907, the WFM withdrew from the IWW, Vincent St. John left the WFM to spend his time organizing the IWW.

Bill Haywood for a time remained a member of both organizations. His murder trial had made Haywood a celebrity, and he was in demand as a speaker for the WFM. His increasingly radical speeches became more at odds with the WFM, and in April 1908, the WFM announced that the union had ended Haywood's role as a union representative. Haywood left the WFM and devoted all his time to organizing for the IWW.[8]: 216–217

Historian Vernon H. Jensen has asserted that the IWW had a "rule or ruin" policy, under which it attempted to wreck local unions which it could not control. From 1908 to 1921, Jensen and others have written, the IWW attempted to win power in WFM locals which had once formed the federation's backbone. When it could not do so, IWW agitators undermined WFM locals, which caused the national union to shed nearly half its membership.[36][37][38][39]

IWW versus the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners left the IWW in 1907, but the IWW wanted the WFM back. The WFM had made up about a third of the IWW membership, and the western miners were tough union men, and good allies in a labor dispute. In 1908, Vincent St. John tried to organize a stealth takeover of the WFM. He wrote to WFM organizer Albert Ryan, encouraging him to find reliable IWW sympathizers at each WFM local, and have them appointed delegates to the annual convention by pretending to share whatever opinions of that local needed to become a delegate. Once at the convention, they could vote in a pro-IWW slate. St. Vincent promised: "once we can control the officers of the WFM for the IWW, the big bulk of the membership will go with them." But the takeover did not succeed.[40]

According to several historians, the

Versus United Mine Workers, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1916

The IWW clashed with the

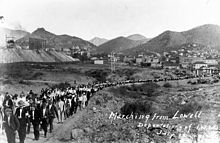

Bisbee Deportation

In November 1916, the 10th convention of the IWW authorized an organizing drive in the Arizona copper mines. Copper was a vital war commodity, so mines were working day and night. During the first months of 1917, thousands joined the Metal Mine Workers' Union #800. The focus of the organizing drive was Bisbee, Arizona, a small town near the Mexican border. Nearly 5000 miners worked in Bisbee's mines. On June 27, 1917, Bisbee's miners went on strike. The strike was effective and non-violent. Demands included the doubling of pay for surface workers, most of them recent immigrants from Mexico, as well as changes in working conditions to make the mines safer. The six-hour day was raised agitationally but held in abeyance. In the early hours of July 12, hundreds of armed vigilantes rounded up nearly two thousand strikers, of whom 1186 were deported in cattle cars and dumped in the desert of New Mexico. In the following days, hundreds more were ordered to leave. The strike was broken at gunpoint.[46]

Other organizing drives

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO) organized more than a hundred thousand migratory farm workers throughout the Midwest and western United States,[47] often signing up and organizing members in the field, in rail yards and in hobo jungles. During this time, the IWW member became synonymous with the hobo riding the rails; migratory farmworkers could scarcely afford any other means of transportation to get to the next jobsite. Railroad boxcars, called "side door coaches" by the hobos, were frequently plastered with silent agitators from the IWW.

Building on the success of the AWO, the IWW's Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) used similar tactics to organize lumberjacks and other timber workers, both in the deep South and the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, between 1917 and 1924. The IWW lumber strike of 1917 led to the eight-hour day and vastly improved working conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Though mid-century historians credited the US Government and "forward thinking lumber magnates" for agreeing to such reforms, an IWW strike forced these concessions.[48]

From 1913 through the mid-1930s, the IWW's Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), proved a force to be reckoned with and competed with AFL unions for ascendance in the industry. Given the union's commitment to international solidarity, its efforts and success in the field come as no surprise. Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers was led by Ben Fletcher, who organized predominantly African American longshoremen on the Philadelphia and Baltimore waterfronts, but other leaders included the Swiss immigrant Walter Nef, Jack Walsh, E.F. Doree, and the Spanish sailor Manuel Rey. The IWW also had a presence among waterfront workers in

Wobblies also played a role in the sit-down strikes and other organizing efforts by the United Auto Workers in the 1930s, particularly in Detroit, though they never established a strong union presence there.

Where the IWW did win strikes, such as in Lawrence, they often found it hard to hold onto their gains. The IWW of 1912 disdained

Government suppression

The IWW's efforts were met with "unparalleled" resistance from Federal, state and local governments in America;

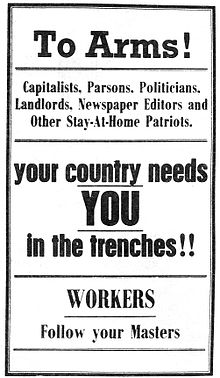

Many IWW members opposed United States participation in World War I. The organization passed a resolution against the war at its convention in November 1916.[55]: 241 This echoed the view, expressed at the IWW's founding convention, that war represents struggles among capitalists in which the rich become richer, and the working poor all too often die at the hands of other workers.

An IWW newspaper, the

In spite of the IWW moderating its vocal opposition, the IWW's antiwar stance made it highly unpopular. Frank Little, the IWW's most outspoken war opponent, was lynched in Butte, Montana, in August 1917, just four months after war had been declared.

During World War I, the U.S. government moved strongly against the IWW. On September 5, 1917, U.S.

Based in large measure on the documents seized September 5, one hundred and sixty-six IWW leaders were indicted by a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes, under the new Espionage Act.[37]: 407 One hundred and one went on trial en masse before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1918. Their lawyer was George Vanderveer of Seattle.[56] They were all convicted—including those who had not been members of the union for years—and given prison terms of up to twenty years. Sentenced to prison by Judge Landis and released on bail, Haywood fled to the Soviet Union where he remained until his death.

In 1917, during an incident known as the Tulsa Outrage, a group of black-robed Knights of Liberty tarred and feathered seventeen members of the IWW in Oklahoma. The attack was cited as revenge for the Green Corn Rebellion, a preemptive attack caused by fear of an impending attack on the oil fields and as punishment for not supporting the war effort. The IWW members had been turned over to the Knights of Liberty by local authorities after they were beaten, arrested at their headquarters and convicted of the crime of vagrancy. Five other men who testified in defense of the Wobblies were also fined by the court and subjected to the same torture and humiliations at the hands of the Knights of Liberty.[57][58][59][60]

In 1919, an Armistice Day parade by the American Legion in Centralia, Washington, turned into a fight between legionnaires and IWW members in which four legionnaires were shot. Which side initiated the violence of the Centralia massacre is disputed, though there had been previous attacks on the IWW hall and businessmen's association had made threats against union members. A number of IWWs were arrested, one of whom, Wesley Everest, was lynched by a mob that night.[61] A bronze plaque honoring the IWW members imprisoned and lynched following the Centralia Tragedy was dedicated in the city's George Washington Park on November 11, 2023. This plaque will be installed on a 2 1/2 ton granite monument when completed in 2024. A pardon request had been delivered to Washington Governor Inslee requesting posthumous pardons for the eight IWW members who were convicted.[62]

Members of the IWW were prosecuted under various State and federal laws and the 1920 Palmer Raids singled out the foreign-born members of the organization.

Organizational schism and aftermath

IWW quickly recovered from the setbacks of 1919 and 1920, with membership peaking in 1923 (58,300 estimated by dues paid per capita, though membership was likely somewhat higher as the union tolerated delinquent members).[63] But recurring internal debates, especially between those who sought either to centralize or decentralize the organization, ultimately brought about the IWW's 1924 schism.[64]

The twenties witnessed the defection of hundreds of Wobbly leaders (including Harrison George, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, John Reed, George Hardy, Charles Ashleigh, Earl Browder and, in his Soviet exile, Bill Haywood) and, following a path recounted by Fred Beal,[65] thousands of Wobbly rank-and-filers to the Communists and Communist organizations.[66][67]

At the beginning of the 1949

1950–2000

Taft–Hartley Act

After the passage of the

At this time, the Cleveland local of the Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union (MMWIU) was the strongest IWW branch in the United States. Leading figures such as Frank Cedervall, who had helped build the branch up for over ten years, were concerned about the possibility of raiding from AFL-CIO unions if the IWW had its legal status as a union revoked. In 1950, Cedervall led the 1500-member MMWIU national organization to split from the IWW, as the Lumber Workers Industrial Union had almost 30 years earlier. This act did not save the MMWIU. Despite its brief affiliation with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, it was raided by the AFL and CIO and defunct by the late 1950s, less than ten years after separating from the IWW.[71]

The loss of the MMWIU, at the time the IWW's largest industrial union, was almost a deathblow to the IWW. The union's membership fell to its lowest level in the 1950s during the Second Red Scare, and by 1955, the union's fiftieth anniversary, it was near extinction, though it still appeared on government lists of Communist-led groups.[12]

1960s rejuvenation

The 1960s civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and various university student movements brought new life to the IWW, albeit with many fewer new members than the great organizing drives of the early part of the 20th century.

The first signs of new life for the IWW in the 1960s were organizing efforts among students in San Francisco and Berkeley, which were hotbeds of student radicalism at the time. This targeting of students resulted in a Bay Area branch of the union with over a hundred members in 1964, almost as many as the union's total membership in 1961. Wobblies old and new united for one more "free speech fight": Berkeley's Free Speech Movement. Riding on this high, the decision in 1967 to allow college and university students to join the Education Workers Industrial Union (IU 620) as full members spurred campaigns in 1968 at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.[72]: 13 The IWW sent representatives to Students for a Democratic Society conventions in 1967, 1968, and 1969, and as the SDS collapsed into infighting, the IWW gained members fleeing this discord. These changes had a profound effect on the union, which by 1972 had 67% of members under the age of 30, with a total of nearly 500 members.[72]: 14

The IWW's links to the 1960s counterculture led to organizing campaigns at counterculture businesses, as well as a wave of over two dozen co-ops affiliating with the IWW under its

These ties to anti-authoritarian and radical artistic and literary currents linked the IWW even more heavily to the 1960s counterculture, exemplified by the publication in Chicago in the 1960s of Rebel Worker by the surrealists Franklin and Penelope Rosemont. One edition was published in London with Charles Radcliffe, who went on to become involved with the Situationist International. By the 1980s, the Rebel Worker was being published as an official organ again, from the IWW's headquarters in Chicago, and the New York area was publishing a newsletter as well.

Return to workplace campaigns

Invigorated by the arrival of enthusiastic new members, the IWW began a wave of organizing drives. These largely took a regional form and they, as well as the union's overall membership, concentrated in Portland, Chicago, Ann Arbor, and throughout the state of California, which when combined accounted for over half of union drives from 1970 to 1979. In Portland, Oregon, the IWW led campaigns at Winter Products (a brass plating plant) in 1972, at a local Winchell's Donuts (where a strike was waged and lost), at the Albina Day Care (where key union demands were won, including the firing of the director of the day care), of healthcare workers at West Side School and the Portland Medical Center, and of agricultural workers in 1974. The latter effort led to the opening of an IWW union hall in Portland to compete with extortionate hiring halls and day labor agencies. Organizing efforts led to a growth in membership, but repeated loss of strikes and organizing campaigns anticipiated the decline of the Portland branch after the mid-1970s, a stagnancy period lasting until the 1990s.[72]: 15

In California, union activities were based in Santa Cruz, where in 1977 the IWW engaged in one of its most ambitious campaigns of the 1970s: an attempt in 1977 to organize 3,000 workers hired under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) in Santa Cruz County. The campaign led to pay raises, the implementation of a grievance procedure, and medical and dental coverage, but the union failed to maintain its foothold, and in 1982 the CETA program was replaced by the Job Training Partnership Act.[72]: 15–16 The IWW won some lasting victories in Santa Cruz, such as campaigns at the Janus Alcohol Recovery Center, the Santa Cruz Law Center, Project Hope, and the Santa Cruz Community Switchboard.[72]: 16

Elsewhere in California, the IWW was active in

In Chicago, the IWW was an early opponent of so-called urban renewal programs and supported the creation of the "Chicago People's Park" in 1969. The Chicago branch also ran citywide campaigns for healthcare, food service, entertainment, construction, and metal workers, and its success with the latter led to an attempt to revive the national Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union, which twenty years earlier had been a major component of the union. Metalworker organizing mostly ended in 1978 after a failed strike at Mid-American Metal in Virden, Illinois. The IWW also became one of the first unions to try to organize fast food workers, with an organizing campaign at a local McDonald's in 1973.[72]: 16

The IWW also built on its existing presence in Ann Arbor, which had existed since student organizing began at the University of Michigan, to launch an organizing campaign at the University Cellar, a college bookstore. The union won National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) certification there in 1979 following a strike, and the store became a strong job shop for the union until it was closed in 1986. The union launched a similar campaign at another local bookstore, Charing Cross Books, but was unable to maintain its foothold there despite reaching a settlement with management.[72]: 17

In the late 1970s, the IWW came to regional prominence in entertainment industry organizing, with an Entertainment Workers Organizing Committee being founded in Chicago in 1976, followed by campaigns organizing musicians in Cleveland in 1977 and Ann Arbor in 1978. The Chicago committee published a model contract which was distributed to musicians in the hopes of raising industry standards, as well as maintaining an active phone line for booking information. IWW musicians such as Utah Phillips, Faith Petric, Bob Bovee, and Jim Ringer also toured and promoted the union,[72]: 17 and in 1987 an anthology album, Rebel Voices, was released.

Other IWW organizing campaigns of the 1970s included a

1990s

In the 1990s, the IWW was involved in many labor struggles and free speech fights, including Redwood Summer, and the picketing of the Neptune Jade in the port of Oakland in late 1997.

In 1996, the IWW launched an organizing drive against

Also in 1996, the IWW began organizing at

In 1998, the IWW chartered a San Francisco branch of the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), which trained hundreds of waterfront workers in health and safety techniques and attempted to institutionalize these safety practices on the San Francisco waterfront.[75]

In 1999, the IWW chartered a local branch of the

Additionally, IWW organizing drives in the late 1990s included a strike at the Lincoln Park Mini Mart in Seattle in 1996, Keystone Job Corps, the community organization ACORN, various homeless and youth centers in Portland, Oregon, sex industry workers, and recycling shops in Berkeley, California. IWW members were also active in the building trades, shipyards, high tech industries, hotels and restaurants, public interest organizations, railroads, bike messengers, and lumber yards.

The IWW stepped in several times to help the rank and file in mainstream unions, including sawmill workers in Fort Bragg in California in 1989, concession stand workers in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1990s, and shipyards along the Mississippi River.

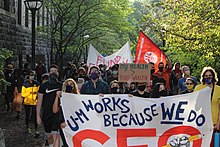

2000–present

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on

Certification Officer[77]

In the early 2000s, the IWW organized Stonemountain and Daughter Fabrics, a fabric shop in Berkeley, California. The shop continues to remain an IWW organized shop. The city of Berkeley's recycling is picked up, sorted, processed and sent out all through two different IWW-organized enterprises. In 2003, the IWW began organizing street people and other non-traditional occupations with the formation of the Ottawa Panhandlers Union. A year later, the Panhandlers Union led a strike by the homeless. Negotiations with the city resulted in the city government promising to fund a newspaper written and sold by the homeless. Between 2003 and 2006, the IWW organized unions at food cooperatives in Seattle, Washington and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The IWW represents administrative and maintenance workers under contract in Seattle, while the union in Pittsburgh lost 22–21 in an NLRB election, only to have the results invalidated in late 2006, based on management's behavior before the election. In 2004, an IWW union was organized in a New York City Starbucks. In 2006, the IWW continued efforts at Starbucks by organizing several Chicago area shops.[78][79]  In Chicago the IWW began an effort to organize bicycle messengers. In September 2004, IWW-organized short haul truck drivers in Stockton, California walked off their jobs and went on a strike. Nearly all demands were met. Despite early victories in Stockton, the truck driver union ceased to exist in mid-2005. In New York City, the IWW has organized immigrant foodstuffs workers since 2005. That summer, workers from Handyfat Trading joined the IWW, and were soon followed by workers from four more warehouses.[80] Workers at these warehouses made gains such as receiving the minimum wage and being paid overtime. In 2006, the IWW moved its headquarters to Cincinnati, Ohio , and in 2010, headquarters was moved back to Chicago, Illinois.

Also in 2006, the IWW Bay Area Branch organized the Landmark Shattuck Cinemas. The Union had been negotiating for a contract with the goal of expanding workplace democracy. Seattle

— Staughton Lynd, 2014.[81] In May 2007, the NYC warehouse workers came together with the Kosher food distributor, and Wild Edibles, a seafood company. Over the course of 2007–08, workers at both shops were illegally terminated for their union activity. In 2008, the workers at Wild Edibles actively fought to get their jobs back and to secure overtime pay owed to them by the boss. In a workplace justice campaign called Focus on the Food Chain, carried out jointly with Brandworkers International, the IWW workers won settlements against employers including Pur Pac, Flaum Appetizing and Wild Edibles.[82][83][84][85]

Besides IWW's traditional practice of organizing industrially, the Union has been open to new methods such as organizing geographically: for instance, seeking to organize retail workers in a certain business district, as in Philadelphia. The union has also participated in worker-related issues as protesting involvement in the war in Iraq, opposing sweatshops and supporting a boycott of Coca-Cola for that company's support of the suppression of workers rights in Colombia. On July 5, 2008, the Seville, Spain, organized a global day of action against alleged Starbucks union busting, in particular the firing of two union members in Grand Rapids and Seville. According to the Grand Rapids Starbucks Workers Union website,[86] pickets were held in several dozen cities in more than a dozen countries.

Washington D.C. The Portland, Oregon General Membership Branch is one of the largest and most active branches of the IWW. The branch holds three contracts currently, two with Janus Youth Programs and one with Portland Women's Crisis Line.[87] There has been some debate within the branch about whether or not union contracts such as this are desirable in the long run, with some members favoring solidarity unionism as opposed to contract unionism and some members believing there is room for both strategies for organizing. The branch has successfully supported workers wrongfully fired from several different workplaces in the last two years. Due to picketing by Wobblies, these workers have received significant compensation from their former employers. Branch membership has been increasing, as has shop organizing. As of 2005, the 100th anniversary of its founding, the IWW had around 5,000 members, compared to 13 million members in the AFL-CIO.[88] Other IWW branches are located in Australia, Austria, Canada, Ireland, Germany, Uganda and the United Kingdom. 2011 Wisconsin general strikeIn early 2011, recall effort" against the governor during the crisis.[90]

Late 2010sIn the mid-2010s, Wobblies in the United States were focused on campaigns to organize the multinational coffeehouse chain Starbucks, the franchised sandwich fast food restaurant chain Jimmy John's, and the multinational supermarket chain Whole Foods Market. The union had about 3,000 members.[91] The IWW moved its headquarters to 2036 West Montrose, Chicago, in 2012.[92] The IWW waged an organizing campaign at Chicago-Lake Liquors in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2013. The store, which advertises itself as the highest-volume liquor store in Minnesota, had a wage cap of $10.50 per hour, but in the face of IWW demands for the wage cap to be lifted, store management fired five organizers. On April 6, the Twin Cities branch of the union responded with a picket around the store informing customers of the situation. This was followed by a second picket on May 4, a day which customarily had heavy business at the store. The union claimed to have made "what should have been an extremely busy Saturday into a quiet afternoon inside the store".[93] After several months, the National Labor Relations Board announced that it found merit in the union's unfair dismissal complaint.[94] As a result, the union and store management agreed to a $32,000 settlement as a form of compensation to the fired workers and the campaign officially ended.

Workers at the Paulo Freire Social Justice Charter School in Holyoke, Massachusetts were organized with the IWW in 2015, hoping to address the "authoritarian leadership" of the school administration and perceived racial bias in hiring.[95] On September 14, 2015, after a year-long organizing campaign, workers at Sound Stage Production in North Haven Connecticut declared their membership in the IWW.[96] Within a week they were threatened with legal action and fired. After several months of negotiation through the National Labor Relations Board, a settlement was reached and the workers agreed to back pay and severance compensation. As part of the campaign, the workers formed the Production Services Collective and continue as a workers cooperative and organizing with IWW-CT. The IWW announced the Burgerville Workers Union (BVWU) in April 2016, which focuses on workers at the Oregon regional fast food chain, Burgerville. A subsidiary of the IWW, the BVWU went public on April 26 at a rally of workers and supporters outside a Portland, Oregon Burgerville location. Upon going public, the BVWU was endorsed by a number of local Oregon community organizations, including union locals, the Portland Solidarity Network, and food and racial justice organizations.[97] It was also endorsed by then-Democratic presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders. The union received pushback with a letter from Burgerville's CEO, Jeff Harvey, being distributed to workers discouraging them from joining the union.[98] In June 2017, Burgerville paid a settlement of $10,000 after an investigation by the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries, which found that the company had violated state-mandated break periods for workers.[99] In April and May 2018 the IWW won NLRB elections in 2 Burgerville Locations. In August 2016, workers at Ellen's Stardust Diner in Manhattan formed Stardust Family United (SFU)[100] under the IWW, driven by the firing of thirty employees, as well as an unpopular new scheduling system.[101] After going public, the union accused Stardust management of retaliatory firings and posting anti-union materials in the restaurant.[102] On September 9, 2016, the 45th anniversary of the ACLU National Prison Project judging it to be the "largest prisoner strike in recent memory".[105][106][107] Initial media coverage was slow, with strike organizers complaining of a "mainstream-media blackout", which could be attributed to the difficulty in communicating with prisoners, as many prisons went on lockdown either in response to prisoner strike activity or in anticipation of it.[103]

COVID-19 pandemic The IWW also organized workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. In May 2020 the IWW established the Voodoo Doughnut Workers Union (DWU) in Portland. The newly formed union delivered a letter to management announcing the formation of a union and demanding higher wages, safety improvements and severance packages for employees laid off because of the coronavirus and Oregon's ongoing "shelter-in-place" order.[108] In February 2021, after months of organizing, DWU workers officially filed for a union certification election with the National Labor Relations Board.[109] The IWW also publicly announced the Second Staff (2S) workers' union in May 2020 at the Faison school, a private school serving students on the autism spectrum in Richmond, Virginia, in response to what the union called a "reckless endangerment of staff and students" in trying to force the school to open too soon.[110] March 2021 saw a rash of organizing with the IWW. On March 9, workers at Moe's Books, an independent used bookstore in Berkeley, California, announced that they received voluntary recognition from Moe's Books management, officially unionizing with the IWW.[111] Shortly after, on March 13, the IWW announced that it was organizing workers at the Socialist Rifle Association (SRA).[112] The union was voluntarily recognized by the SRA the following day. Two days later, on March 16, staff at the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (OVEC) announced their intent to unionize with the IWW, and requested voluntary recognition from management. In organizing, the OVEC workers seek to gain "a standardized pay scale, an equitable discipline policy, and the right to union representation at any meeting wherein matters affecting staff pay, hours, benefits, advancement, or layoffs may be discussed or voted on".[113] The IWW is the first union in the United States to ratify a union contract for fast food workers. Five Oregon locations of Burgerville are unionized,[114] as well as one location of Voodoo Doughnut in downtown Portland.[115] AustraliaAustralia encountered the IWW tradition early. In part, this was due to the local De Leonist Socialist Labor Party following the industrial turn of the US SLP. The SLP formed an IWW Club in Sydney in October 1907. Members of other socialist groups also joined it, and the relationship with the SLP soon proved to be a problem. The 1908 split between the Chicago and Detroit factions in the United States was echoed by internal unrest in the Australian IWW from late 1908, resulting in the formation of a pro-Chicago local in Adelaide in May 1911 and another in Sydney six months later. By mid-1913 the "Chicago" IWW was flourishing and the SLP-associated pro-Detroit IWW Club in decline.[116] In 1916 the "Detroit" IWW in Australia followed the lead of the US body and renamed itself the Workers' International Industrial Union.[117]

The early Australian IWW used a number of tactics from the US, including free speech fights. It tended to cooperate where possible with existing unions rather than forming its own, and in contrast with the US body took an extremely open and forthright stand against involvement in World War One. The IWW cooperated with many other unions, encouraging industrial unionism and militancy. In particular, the IWW's strategies had a large effect on the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union. The AMIEU established closed shops and workers councils and effectively regulated management behavior toward the end of the 1910s.  The IWW opposed the First World War from 1914 onward and in many ways fought against Monty Miller .

The IWW continued illegally operating with the aim of freeing its class war prisoners and briefly fused with two other radical tendencies—from the old Socialist parties and Trades Halls—to form a larval communist party at the suggestion of the militant revolutionist and Council Communist Adela Pankhurst. The IWW left the Communist Party of Australia shortly after its formation.

By the early 1930s, most Australian IWW branches had dispersed as the Communist Party grew in influence.[121]  The Australian IWW has grown since the 1940s, but have been unsuccessful in securing union representation. "Bump Me Into Parliament"[124] is the most notable Australian IWW song, and is still current. It was written by ship's fireman William "Bill" Casey, later Secretary of the Seaman's Union in Queensland.[119] New ZealandAustralian influence was strong in early 20th century left-wing groups, and several founders of the New Zealand Labour Party (e.g. Bob Semple) were from Australia. The trans-Tasman interchange was two-way, particularly for miners. Several Tasmanian Labour "groupings" in the 1890s cited their earlier New Zealand experience of activism e.g. later premier Robert Cosgrove, and also Chris Watson from New South Wales.[125] "Wobbly" activists in New Zealand pre-WWI were John Benjamin King and H. M. Fitzgerald (an adherent of the De Leon school) from Canada. Another was Robert Rivers La Monte from America, who was (briefly) an organizer for the New Zealand Socialist Party (as was Fitzgerald). IWW strongholds were Auckland "a city with the demographic characteristics of a frontier town"; Wellington where a branch survived briefly and in mining towns, on the wharves and among laborers.[126] Canada The IWW was active in Canada from a very early point in the organization's history, especially in Western Canada, primarily in British Columbia. The union was active in organizing large swaths of the lumber and mining industry along the coast, in the Interior of British Columbia, and Vancouver Island. Joe Hill wrote the song "Where the Fraser River Flows" during this period when the IWW was organizing in British Columbia. Some members of the IWW had relatively close links with the Socialist Party of Canada.[127] Canadians who went to Australia and New Zealand before WWI included John Benjamin King and H. M. Fitzgerald (an adherent of the De Leon school).[126] First World War. The impact of Ginger Goodwin influenced various left and progressive groups in Canada, including a progressive group of MPs in the House of Commons called the Ginger Group .

Despite the IWW being banned as a subversive organization in Canada during the First World War, the organization rebounded swiftly after being unbanned after the war, reaching a post-WWI high of 5600 Canadian members in 1923. In 1936, the IWW in Canada supported the FLQ during the October Crisis. As a sign of the times, the old Canadian Administration in Port Arthur was dissolved in 1973 and replaced by a Canadian Regional Organizing Committee, meaning that Canadian branches would be administered by the General Administration in the United States. IWW activity in Canada began to shift largely toward strike support and labor activism, such as support for the 1973 Artistic Woodwork strike in Toronto. By the 1980s, the Vancouver branch was supporting unemployed activism through the Vancouver Unemployed Action Centre by helping to shut down the scam operation Vancouver Job Mart and supporting the campaign for a fixed-income transit pass.

By the end of the 1990s, the IWW in Canada was following the general pattern of ascendancy, winning government recognition at Harvest Collective in Manitoba, the first shop certified in Canada since 1919. During the 2000s, branches were chartered in several new cities, and existing branches were revitalized. The dissolved Canadian Regional Organizing Committee was refounded in 2011. In 2009, after Starbucks established policies that meant demotions and loss of salary for some workers, the Quebec branches of Montreal and Sherbrooke helped found the Starbucks Workers' Union (STTS) which made a breakthrough in Quebec City at an establishment in Sainte-Foy.[130] Leaders Simon Gosselin, Dominic Dupont and Andrew Fletcher were harassed in the months following unionization, and union efforts were defeated by law firm Heenan Blaike in the series of hearings before Quebec Labor Relations Board.[131] Today the IWW remains active in the country with branches in Montréal.[132] In August 2009, Canadian members voted to ratify the constitution of the Canadian Regional Organizing Committee (CanROC) to improve inter-branch coordination and communication. Affiliated branches are Winnipeg, Ottawa-Outaouais, Toronto, Windsor, Sherbrooke, Montréal, and Québec City. Each branch elects a representative to make decisions on the Canadian board. There were originally three officers, the Secretary-Treasurer, Organizing Department Liaison, and Editor of the Canadian Organizing Bulletin.[133] In 2016, CanROC members voted to split the Secretary-Treasurer role into separate Regional Secretary and Regional Treasurer positions.

There are currently five job shops in Canada: Libra Knowledge and Information Services Co-op in Toronto, ParIT Workers Cooperative in Winnipeg, the Windsor Button Collective, the buskers, street vendors, the homeless, scrappers, and panhandlers. In the summer of 2004, the Union led a strike by the homeless (the Homeless Action Strike) in Ottawa. The strike resulted in the city agreeing to fund a newspaper created and sold by the homeless on the street. On May 1, 2006, the Union took over the Elgin Street Police Station for a day. A similar IWW organization, the Street Labourers of Windsor (SLOW), has garnered local,[134] provincial,[135] and national[136] news coverage for its organizing efforts in 2015.

Recently, the IWW has also engaged in campaigns among Québec fast food chain Frite Alors! in 2016.

EuropeGermany, Luxembourg, Switzerland, AustriaThe IWW started to organize in Germany following the First World War. Fritz Wolffheim played a significant role in establishing the IWW in Hamburg. A German Language Membership Regional Organizing Committee (GLAMROC) was founded in December 2006 in Cologne. It encompasses the German-language area of Germany, Luxembourg, Austria, and Switzerland with branches or contacts in 16 cities.[137] In 2023, the GLAMROC is reported as having roughly 500 members in good standing. United Kingdom and IrelandThe regional body of the union in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland is the Wales, Ireland, Scotland, England Regional Administration (WISERA). Formerly known as the Britain and Ireland Regional Administration (BIRA), its name was changed as a result of a referendum vote by WISERA members.[138] Early historyThe E. J. B. Allen founding the Industrialist Union and developing links with the Chicago-based IWW. Allen's group soon disappeared, but the first IWW group in Britain was founded by members of the Industrial Syndicalist Education League led by Guy Bowman in 1913.

The IWW was present, to varying extents, in many of the struggles of the early decades of the 20th century, including the UK general strike of 1926 and the dockers' strike of 1947. During the Spanish Civil War, a Wobbly from Neath, who had been active in Mexico, trained volunteers in preparation for the journey to Spain, where they joined the International Brigades to fight against Franco.[21]

During the decade after World War II, the IWW had two active branches in London and Glasgow. These soon died off, before a modest resurgence in northwest England during the 1970s. Membership Between 2001 and 2003, there was a marked increase in UK membership, with the creation of the Hull General Membership Branch. During this time the Hull branch had 27 members of good standing, at that time the largest branch outside of the United States. By 2005, there were around 100 members in the United Kingdom. For the IWW's centenary, a stone was laid (51°41.598′N 4°17.135′W / 51.693300°N 4.285583°W), in a public access forest near Llanelli, Wales, commemorating the centenary of the union. In addition, sequoias were planted as a memorial to US IWW and Earth First! activist Judi Bari. The IWW formally registered by the UK government as a recognised trade union in 2006. The IWW currently has a presence in several major urban areas as well as regional centers, with chartered branches in London, Glasgow (Clydeside GMB), Bradford, Bristol, Dorset, Edinburgh, Ireland, Leeds, Leicestershire, Manchester, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire, Northumbria, Nottingham, Reading, Sheffield, Wales, and the Tyne and Wear and West Midlands areas. Overall, membership has increased rapidly; in 2014, the union reported a total UK membership of 750,[139] which increased to 1000 by April 2015.[140] In 2016, the 1,500 member limit was passed. Campaigns IWW members were involved in the dockers' strike that took place between 1995 and 1998, and numerous other events and struggles throughout the 1990s and 2000s, including the successful unionizing of several workplaces, such as support workers for the Scottish Socialist Party .

Recently, the IWW has focused its efforts on health and education workers, publishing a national industrial newsletter for health workers and a specific bulletin for workers in the National Blood Service. In 2007 it launched a campaign alongside the anti-capitalist group No Sweat which attempted to replicate some of the successes of the US IWW's organizing drives amongst Starbucks workers. In the same year its healthworkers' network launched a national campaign against cuts in the National Blood Service, which is ongoing.

Also in 2007, IWW branches in Glasgow University's campuses (The Crichton) in Dumfries.[141] The campaign united IWW members, other unions, students and the local community to build a powerful coalition. Its success, coupled with the National Blood Service campaign, has raised the IWW's profile significantly since then.

In 2011, the IWW representing cleaners at the Guildhall won back pay and the right to collective negotiation with their employers, Ocean. Also in 2011, branches of the IWW were set up in Lincoln, Manchester, and Sheffield (notably workers employed by Pizza Hut). The Edinburgh General Membership Branch of the IWW along with other branches of the IWW's Scottish section voted in 2014 to become a signatory to the "From Yes to Action Statement" produced by the Autonomous Centre of Edinburgh. In 2015, along with similar groups such as the Edinburgh Coalition Against Poverty and Edinburgh Anarchist Federation, they joined the Scottish Action Against Austerity network.[142] In 2016, WISERA promoted a campaign targeting couriers working for companies such as Deliveroo.[143] Iceland and GreeceAn Iceland Regional Organizing Committee (IceROC)[144] was chartered in 2015. The union has become a trailblazer in supporting sex workers in Iceland, who lack access to services which do not automatically treat them as victims of abuse.[145] Also in 2015, a Greek Regional Organizing Committee (GreROC) was chartered. In July of that year, it released a statement condemning the Greek government's response to the results of the 2015 Greek bailout referendum, saying that "despite the Left tone of dignity that the Left governmental administrators use, this is a one-way blackmail. We need a radical change of shift, not in words but in action."[146] AfricaSouth AfricaThe IWW has a rich and complex history in South Africa, with an original South African IWW organization being founded in 1910 and existing through most of the 1910s until disintegrating by around 1916.[147] The union's insistence on multiracial unionism set it at odds with the white trade union movement and brought severe political repression from the apartheid-era South African government. The major South African port of Durban was an important link in the IWW's international network which was largely maintained by its Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union, that connected the mainline North American IWW to ports in Africa, India, South America, and Australasia. After the collapse of the formal IWW organization in South Africa, it was succeeded by an Communist Party of South Africa, which opposed syndicalist tendencies in the unions.[148]

Almost a hundred years later, multiple attempts were made to rebuild the South African IWW, with a short-lived South African Regional Organizing Committee being founded in the early 2000s in Durban and attempts made to build a branch in Cape Town in the early 2010s, with neither resulting in success.[149] Sierra Leone and UgandaIn 1997, there were 3,240[150] workers in Sierra Leone, mostly miners, who registered themselves as IWW members in Sierra Leone government records largely independently of the international General Administration in Chicago (i.e. without the official issuing of membership cards or taking of dues). Contact between the Sierra Leone members and headquarters was lost after a military coup which was an episode in the Sierra Leone Civil War, which ended in 2002. The intensification of the civil war provoked some members, including the only official union delegate in the country, to flee to Guinea.[151][74] In 2012, IWW members in Uganda formed a Ugandan Regional Organizing Committee (ROC) and began to raise funds to establish a Ugandan office for the IWW. Upon discovery that Ugandan union officers had violated the IWW constitution in multiple ways, such as by permitting employers to join, the ROC was dissolved.[152] Folk music and protest songs

One Wobbly characteristic since their inception has been a penchant for song. To counteract management sending in the I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night". Perhaps the best known IWW song is "Solidarity Forever". The songs have been performed by dozens of artists, and Utah Phillips performed the songs in concert and on recordings for decades. Other prominent IWW songwriters include Ralph Chaplin who authored "Solidarity Forever", and Leslie Fish .

The Finnish IWW community produced several folk singers, poets and songwriters, the most famous being Matti Valentine Huhta (better known as T-Bone Slim), who penned "The Popular Wobbly" and "The Mysteries of a Hobo's Life". Slim's poem "The Lumberjack's Prayer" was recorded by Studs Terkel on labor singer Bucky Halker's album Don't Want Your Millions. Hiski Salomaa, whose songs were composed entirely in Finnish (and Finglish), remains a widely recognized early folk musician in his native Finland as well as in sections of the Midwest United States, Northern Ontario, and other areas of North America with high concentrations of Finns. Salomaa, who was a tailor by trade, has been referred to as the Finnish Woody Guthrie. Arthur Kylander, who worked as a lumberjack, is a lesser known, but important Finnish IWW folk musician. Kylander's lyrics range from the difficulties of the immigrant laborer's experience to more humorous themes. Arguably, the wanderer, a recurring theme in Finnish folklore dating back to pre-Christian oral tradition (as with Lemminkäinen in the Kalevala), translated quite easily to the music of Huhta, Salomaa, and Kylander; each of whom has songs about the trials and tribulations of the hobo. LiteratureMuch of the plot of the U.S. trilogy, a series of three novels by American writer John Dos Passos—comprising the novels The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), and The Big Money (1936)—is devoted to the IWW, and several of the more sympathetic characters are its members. Written at the time when Dos Passos was politically on the Left, the novels reflect the author's sympathy, at the time of writing, for the IWW and his outrage at its suppression, for which he expresses his deep grudge for President Woodrow Wilson .

Karl Marlantes's 2019 novel Deep River explores labor issues in the early 1900s in the US and the consequences for an immigrant Finnish family. The book focuses on a female family member who becomes an organizer for the IWW in the dangerous logging industry. Both pro- and anti-labor viewpoints are examined, with special attention given to IWW strikes and the backlash against the labor movement during World War I.[154] LingoWobbly lingo is a collection of Some words and phrases believed to have originated within Wobbly lingo have gained cultural significance outside of the IWW. For example, from Joe Hill's song "The Preacher and the Slave", the expression pie in the sky has passed into common usage, referring to a "preposterously optimistic goal".[161] Notable membersFormer lieutenant governor of Colorado founding convention,[55]: 242–278 although it is unknown if he became a member. It has long been rumored, but not proven, that baseball legend Honus Wagner was also a Wobbly. Senator Joseph McCarthy accused Edward R. Murrow of having been an IWW member, which Murrow denied.[162] Some of the organization's most famous recent members include Noam Chomsky, Tom Morello, mixed martial arts fighter Jeff Monson, Andy Irvine, and late anthropologist David Graeber .

See also

Explanatory notesReferences

Further readingArchives

Official documents

Books

Periodicals

Documentary films

External links

|