North American English regional phonology

North American English regional phonology is the study of variations in the pronunciation of spoken

The most recent work documenting and studying the phonology of North American English dialects as a whole is the 2006

Overview

Regional dialects in North America are historically the most strongly differentiated along the Eastern seaboard, due to distinctive speech patterns of urban centers of the American East Coast like Boston, New York City, and certain Southern cities, all of these accents historically noted by their London-like r-dropping (called non-rhoticity), a feature gradually receding among younger generations, especially in the South. The Connecticut River is now regarded as the southern and western boundary of the traditional New England accents, today still centered on Boston and much of Eastern New England. The Potomac River generally divides a group of Northeastern coastal dialects from an area of older Southeastern coastal dialects. All older Southern dialects, however, have mostly now receded in favor of a strongly rhotic, more unified accent group spread throughout the entire Southern United States since the late 1800s and into the early 1900s. In-between the two aforementioned rivers, some other variations exist, most famous among them being New York City English.

Outside of the Eastern seaboard, virtually all other North American English (both in the U.S. and Canada) has been firmly rhotic (pronouncing all r sounds), since the very first arrival of English-speaking settlers. An exception is the English spoken in the insular and culturally British-associated city of Victoria, British Columbia, where non-rhoticity is one of several features in common with British English, and despite the decline of the quasi-British "Van-Isle" accent once spoken throughout southern Vancouver Island, this makes it unique as the only distinguishable local dialect of Canadian English spoken west of Quebec.[1]

Rhoticity in central and western North America is a feature shared today with the English of Ireland, for example, rather than most of the English of England, which has become non-rhotic since the late 1700s. The sound of Western U.S. English, overall, is much more homogeneous than Eastern U.S. English. The interior and western half of the country was settled by people who were no longer closely connected to England, living farther from the British-influenced Atlantic Coast.

Certain particular vowel sounds are the best defining characteristics of regional North American English including any given speaker's presence, absence, or transitional state of the so-called

Another prominent differentiating feature in regional North American English is

One phenomenon apparently unique to North American U.S. accents is the irregular behavior of words that in the British English standard,

Classification of regional accents

Hierarchy of regional accents

The findings and categorizations of the 2006 The Atlas of North American English (or ANAE), use one well-supported way to hierarchically classify North American English accents at the level of broad geographic regions, sub-regions, etc. The North American regional accent represented by each branch, in addition to each of its own features, also contains all the features of the branch it extends from.

- NORTH AMERICA

- CANADA and WESTERN UNITED STATES = conservative /oʊ/ + /u/ is fronted + cot–caught merger

- Atlantic Canada = /ɑ/ is fronted before /r/ + full Canadian raising

- tensed before /ɡ/[2]+ Canadian Shift ([a] ← /æ/ ← /ɛ/ ← /ɪ/)

- Inland Canada = full Canadian raising

-

- New York City = R-dropping

- NEW ENGLAND and NORTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES = conservative /oʊ/ + conservative /u/ + conservative /aʊ/[3] + pin–pen distinction

- North = cot–caught distinction + /ɑ/ is fronted before /r/

- Eastern New England = R-dropping[9] + full Canadian raising

- father–bother distinction+ /ɑ/ is fronted before /r/

- Rhode Island = cot–caught distinction + conservative /ɑ/ before /r/

- tensed before /ɡ/[10]

- Wisconsin and Minnesota = haggle–Hegel merger[10]

- North = cot–caught distinction + /ɑ/ is fronted before /r/

- SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES = /aʊ/ is fronted + /oʊ/ is fronted + /u/ is fronted

- Southeastern Super-Region = cot–caught distinction or near-merger + /ʌ/ is fronted

- Mid-Atlantic = Mid-Atlantic /æ/ split system + Mary–marry–merry 3-way distinction[11]

- Midland = /aɪ/ can be monophthongized before resonants[12] + variable pin–pen merger

- South = /aɪ/ is monophthongized, encouraging the Southern Shift ([a] ← /aɪ/ ← /eɪ/ ← /i/ and drawling) + pin–pen merger

- Inland South = Back Upglide Chain Shift ([æɔ] ← /aʊ/ ← /ɔ/ ← /ɔɪ/)fill–feel merger

- Inland South = Back Upglide Chain Shift ([æɔ] ← /aʊ/ ← /ɔ/ ← /ɔɪ/)

- Marginal Southeast = cot–caught merger

- full–fool merger

- Pittsburgh = /aʊ/ can be monophthongized before /l/ and /r/, and in unstressed function words[14]

- Southeastern Super-Region = cot–caught distinction or near-merger + /ʌ/ is fronted

- CANADA and WESTERN UNITED STATES = conservative /oʊ/ + /u/ is fronted + cot–caught merger

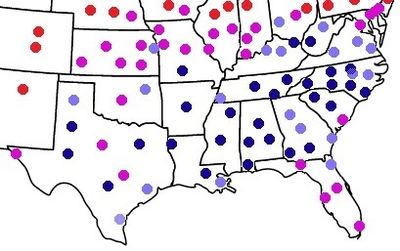

Maps of regional accents

- Western

- The Western dialect, including Californian and New Mexican sub-types (with Pacific Northwest English also, arguably, a sub-type), is defined by:

- North Central

- The North Central ("Upper Midwest") dialect, including an Upper Michigan sub-type, is defined by:

- Inland Northern

- The Inland Northern ("Great Lakes") dialect is defined by:

- No cot–caught merger: the cot vowel is [ɑ̈~a] and caught vowel is [ɒ]

- /æ/ is universally [ɛə], the triggering event for the

- GOAT is [oʊ~ʌo]

- Midland

- The Midland dialect is defined by:

- WPA

- The Western Pennsylvania dialect, including its advanced Pittsburgh sub-type, is defined by:

- Cot–caught merger to [ɒ~ɔ], the triggering event for the Pittsburgh Chain Shift in the city itself ([ɒ~ɔ] ← /ɑ/ ← /ʌ/) but no trace of the Canadian Shift[19]

- /oʊ/ is [əʊ~ɞʊ][20]

- Full–fool–foal mergerto [ʊl~ʊw]

- Specifically in Greater Pittsburgh, /aʊ/ is [aʊ~a], particularly before /l/ and /r/, and in unstressed function words[14]

- Southern

- The Southern dialects, including several sub-types, are defined by:

- Variable rhoticity (parts of Louisiana are still non-rhotic, even among younger people )

- No cot–caught merger: the cot vowel is [ɑ] and caught vowel is [ɑɒ]

- /aɪ/ is [a] at least before /b/, /d/, /ɡ/, /v/, or /z/, or word-finally, and potentially elsewhere, the triggering event for the Southern Shift ([a] ← /aɪ/ ← /eɪ/ ← /i/)

- "Southern drawl" may break short

- MOUTH is [æo], the triggering event for the Back Upglide Shift in more advanced sub-types ([æo] ← /aʊ/ ← /ɔ/ ← /ɔɪ/)[13]

- GOAT is [əʉ~əʊ]

- Mid-Atlantic

- The Mid-Atlantic ("Delaware Valley") dialect, including Philadelphia and Baltimore sub-types, is defined by:

- No cot–caught merger: the cot vowel is [ɑ̈~ɑ] and caught vowel is [ɔə~ʊə]; this severe distinction is the triggering event for the Back Vowel Shift before /r/ (ʊr ← /ɔ(r)/ ← /ɑr/)[22][23]

- Unique Mid-Atlantic /æ/ split system: the bad vowel is [eə] and sad vowel is [æ]

- GOAT is [əʊ]

- MOUTH is [ɛɔ][18]

- No Mary–marry–merry merger

- NYC

- The New York City dialect (with New Orleans English an intermediate sub-type between NYC and Southern) is defined by:

- No cot–caught merger: the cot vowel is [ɑ̈~ɑ] and caught vowel is [ɔə~ʊə]; this severe distinction is the triggering event for the Back Vowel Shift before /r/ (/ʊə/ ← /ɔ(r)/ ← /ɑr/)[22]

- Non-rhoticity or variable rhoticity

- Unique New York City /æ/ split system: the bad vowel is [eə] and bat vowel is [æ]

- GOAT is [oʊ~ʌʊ]

- No Mary–marry–merry merger

- father–bothernot necessarily merged

- ENE

- Eastern New England dialect, including Maine and Boston sub-types (with Rhode Island English an intermediate sub-type between ENE and NYC), is defined by:

- Cot–caught merger to [ɒ~ɑ] (lacking only in Rhode Island)

- Non-rhoticity or variable rhoticity[16][24]

- MOUTH is [ɑʊ~äʊ][25]

- GOAT is [oʊ~ɔʊ]

- GOOSE is [u]

- Commonly, the starting points of /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ in a voiceless consonants: [əɪ~ʌɪ] and [əʊ~ʌʊ], respectively

- Possibly no Mary–marry–merry merger

- No father–bother merger (except in Rhode Island): the father vowel is [a~ɑ̈] and bother vowel is [ɒ~ɑ][26]

All regional Canadian English dialects, unless specifically stated otherwise, are

- Standard Canadian

- The Standard Canadian dialect, including its most advanced Inland Canadian sub-type and others, is defined by:

- Cot–caught merger to [ɒ], the triggering event for the Canadian Shift in more advanced sub-types ([ɒ] ← /ɑ/ ← /æ/ ← /ɛ/)[20]

- /æ/ is raised to [ɛ] or even [e(ɪ)] when before /ɡ/[10]

- Especially in Inland Canadian, beginnings of /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ in a

- START is [ɑɹ~ʌɹ][29]

- GOAT is [oʊ]

- GOOSE is [ʉu], except before /l/ where it is [u].[30]

- Atlantic Canadian

- The Atlantic Canadian ("Maritimer") dialect, including Cape Breton, Lunenburg, and Newfoundland sub-types, is defined by:

- Cot–caught merger to [ɑ̈], but with no trace of the

- START is [ɐɹ~əɹ][31]

- GOAT is [oʊ]

Chart of regional accents

| Accent | Most populous urban center | Strong /aʊ/ fronting | Strong /oʊ/ fronting | Strong /u/ fronting | Strong /ɑ/ fronting before /r/ | Cot–caught merger | Mary–marry–merry merger |

Pin–pen merger |

/æ/ raising system |

Chain shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Canadian | Halifax, NS | Mixed | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Pre-nasal (mixed) | none |

Inland Northern |

Chicago, IL | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | General or Pre-nasal[6][7] | Northern Cities

|

Mid-Atlantic |

Philadelphia, PA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Split | Back Vowel |

| Midland | Columbus, OH | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mixed | Yes | Mixed | Pre-nasal | none |

| New York City | New York City, NY | Yes | No | No[32] | No | No | No | No | Split | Back Vowel |

| North-Central | Minneapolis, MN | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Pre-nasal & -velar | none |

| Eastern New England | Boston, MA | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Pre-nasal | none |

| Southern | San Antonio, TX | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mixed | Yes | Yes | Southern | Southern & Back Upglide |

| Standard Canadian | Toronto, ON | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Pre-nasal & -velar | Canadian

|

| Western | Los Angeles, CA | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Pre-nasal | none ( California )

|

| Western Pennsylvania | Pittsburgh, PA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Mixed | Pre-nasal | Pittsburgh |

Alternative classifications

Combining information from the phonetic research through interviews of Labov et al. in the ANAE (2006) and the phonological research through surveys of Vaux (2004), Hedges (2017) performed a

The defining particular pronunciations of particular words that have more than an 86% likelihood of occurring in a particular cluster are: pajamas with either the phoneme /æ/ or the phoneme /ɑ/; coupon with either /ju/ or /u/; Monday with either /eɪ/ or /i/; Florida with either /ɔ/ or other possibilities (such as /ɑ/); caramel with either two or three syllables; handkerchief with either /ɪ/ or /i/; lawyer as either /ˈlɔɪ.ər/ or /ˈlɔ.jər/; poem with either one or two syllables; route with either /u/ or /aʊ/; mayonnaise with either two or three syllables; and been with either /ɪ/ or other possibilities (such as /ɛ/). The parenthetical words indicate that the likelihood of their pronunciation occurs overwhelmingly in a particular region (well over 50% likelihood) but does not meet the >86% threshold set by Hedges (2017) for what necessarily defines one of the six regional accents. Blank boxes in the chart indicate regions where neither pronunciation variant particularly dominates over the other; in some of these instances, the data simply may be inconclusive or unclear.[33]

| Presumed accent region (cluster) | pajamas | coupon | Monday | Florida | caramel | handkerchief | lawyer | poem | route | mayonnaise | been |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | /æ/ | /ju/ | /eɪ/ | /ɔ/ | 2 syll. | (/ɪ/) | (/ɔɪ/) | ||||

| South | /ɑ/ | (/ju/) | (/eɪ/) | (/ɔ/) | 3 syll. | /ɪ/ | /ɔj/ | 2 syll. | (/ɪ/) | ||

| West | /ɑ/★ | (/u/) | /eɪ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɪ/ | /ɔɪ/ | (2 syll.) | (/ɪ/) | |||

| New England | (/u/) | /eɪ/ | (/ɔ/) | 3 syll. | /ɔɪ/ | (2 syll.) | /u/ | 3 syll. | |||

| Midland | /æ/ | /u/ | /eɪ/ | /ɔ/ | 2 syll. | /ɔɪ/★ | (2 syll.) | ||||

| Mid-Atlantic & NYC |

/ɑ/ | /u/ | /eɪ/ | 3 syll. | /ɪ/ | /ɔɪ/ | (2 syll.) | /u/ | (3 syll.) | /ɪ/ |

★ Hedges (2017) acknowledges that the two pronunciations marked by this star are discrepancies of her latent class analysis, since they conflict with Vaux (2004)'s surveys. Conversely, the surveys show that /æ/ is the much more common vowel for pajamas in the West, and /ɔɪ/ and /ɔj/ are in fact both common variants for lawyer in the Midland.

General American

General American is an umbrella accent of American English perceived by many Americans to be "neutral" and free of regional characteristics. A General American accent is not a specific well-defined

Canada and Western United States

The English dialect region encompassing the

Atlantic Canada

The accents of

Inland Canada

All of Canada, except the Atlantic Provinces and French-speaking Québec, speaks Standard Canadian English: the relatively uniform variety of North American English native to inland and western Canada. The vowel [ɛ] is raised and diphthongized to [ɛɪ] or [eɪ] and [æ] as [eɪ] all before /ɡ/ and /ŋ/, merging words like leg and lag [leɪɡ]; tang is pronounced [teɪŋ].

The

Increasing numbers of Canadians have a feature called "

Pacific Northwest

The English of the Pacific Northwest, a region extending from British Columbia south into the Northwestern United States (particularly Washington and Oregon), is closely linguistically related to that of Inland Canada and that of California.

Like in Inland Canada, before /g/, /ɛ/ and /æ/ are raised, and /eɪ/ is lowered, sometimes leading to three-way merger. Canadian raising of /aɪ/ exists throughout the region, but the raising of /aʊ/ is more restricted to Canadian part.[38] The Canadian shift was observed in Vancouver independently of the shift further east,[39] and has now spread throughout the region. [40] In Oregon, a split in /oʊ/ occurs where it fronts except before /l/ and nasals, similar to California.[41]

California

California, the most populated U.S. state, has been documented as having some notable new subsets of Western U.S. English. Some youthful urban Californians possess a vowel shift partly identical to the

Greater New York City

As in Eastern New England, the accents of New York City, Long Island, and adjoining New Jersey cities are traditionally non-rhotic, while other greater New York area varieties falling under the same sweeping dialect are usually rhotic or variably rhotic. Metropolitan New York shows the back GOAT and GOOSE vowels of the North, but a fronted MOUTH vowel. The vowels of cot [kɑ̈t] and caught [kɔət] are distinct; in fact the New York dialect has perhaps the highest realizations of /ɔ/ in North American English, even approaching [oə] or [ʊə]. Furthermore, the father vowel is traditionally kept distinct from either vowel, resulting in a three "lot-palm-father distinction".[5]

The r-colored vowel of cart is back and often rounded [kɒt], and not fronted as it famously is in Boston. New York City and its surrounding areas are also known for a complicated[

Northern and North-Central United States

One vast super-dialectal area commonly identified by linguists is "the North", usually meaning New England, inland areas of the

North

The traditional and linguistically conservative North (as defined by the Atlas of North American English) includes /ɑ/ being often raised or fronted before /r/, or both, as well as a firm resistance to the cot-caught merger (though possibly weakening in dialects reversing the fronting of /ɑ/[6]). Maintaining these two features, but also developing several new ones, a younger accent of the North is now predominating at its center, around the Great Lakes and away from the Atlantic coast: the Inland North.

Inland North

The Inland North is a dialect region once considered the home of "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis for

New England

New England does not form a single unified dialect region, but rather houses as few as four native varieties of English, with some linguists identifying even more. Only Southwestern New England (Connecticut and western Massachusetts) neatly fits under the aforementioned definition of "the North". Otherwise, speakers, namely of Eastern New England, show very unusual other qualities. All of New England has a

Northeastern New England

The local and historical dialect of the coastal portions of New England, sometimes called

Rhode Island

Rhode Island, dialectally identified as "Southeastern New England", is sometimes grouped with the Eastern New England dialect region, both by the dialectologists of the mid–20th century and in certain situations by the Atlas of North American English; it shares Eastern New England's traditional non-rhoticity (or "R Dropping"). A key linguistic difference between Rhode Island and the rest of the Eastern New England, however, is that Rhode Island is subject to the father–bother merger and yet neither the cot–caught merger nor /ɑ/ fronting before /r/. Indeed, Rhode Island shares with New York and Philadelphia an unusually high and back allophone of /ɔ/ (as in caught), even compared to other communities that do not have the cot–caught merger. In the Atlas of North American English, the city of Providence (the only Rhode Island community sampled by the Atlas) is also distinguished by having the backest realizations of /u/, /oʊ/, and /aʊ/ in North America. Therefore, Rhode Island English aligns in some features more with Boston English and other features more with New York City English.

Western New England

Recognized by research since the 1940s is the linguistic boundary between Eastern and Western New England, the latter settled from the

North Central

The North Central or Upper Midwest dialect region of the United States extends from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan westward across northern Minnesota and North Dakota into the middle of Montana.[citation needed] Although the Atlas of North American English does not include the North Central region as part of the North proper, it shares all of the features listed above as properties of the North as a whole. The North Central is a linguistically conservative region; it participates in few of the major ongoing sound changes of North American English. Its /oʊ/ (GOAT) and /eɪ/ (FACE) vowels are frequently even monophthongs: [o] and [e], respectively. The movie Fargo, which takes place in the North Central region, famously features strong versions of this accent.[44] Unlike most of the rest of the North, the cot–caught merger is prevalent in the North Central region. Like in Canada, /æ/ TRAP is raised before /g/. In addition, some speakers will show NCS features, like /æ/ TRAP raising towards [ɛə] and /ɑ/ LOT fronting towards [ä].

Southeastern United States

The 2006

Essentially all of the modern-day Southern dialects, plus dialects marginal to the South (some even in geographically and culturally "Northern" states), are thus considered a subset of this super-region:

- Fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/: The syllable break between two vowels (as in going or poet), in which /oʊ/ remains back in the mouth as [ɔu~ɒu].[49]

- Lacking or transitioning cot–caught merger: The historical distinction between the two vowels sounds /ɔ/ and /ɒ/, in words like caught and cot or stalk and stock is mainly preserved.[46] In much of the South during the 1900s, there was a trend to lower the vowel found in words like stalk and caught, often with an upglide, so that the most common result today is the gliding vowel [ɑɒ]. However, the cot–caught merger is becoming increasingly common throughout the United States, thus affecting Southeastern (even some Southern) dialects, towards a merged vowel [ɑ].[50] In the South, this merger, or a transition towards this merger, is especially documented in central, northern, and (particularly) western Texas.[51]

- Yat dialect of New Orleans or the anomalous dialect of Savannah, Georgia. The pin–pen merger has also spread beyond the South in recent decades and is now found in isolated parts of the West and the southern Midwestas well.

Midland

A band of the United States from Pennsylvania west to the

, as in much of the country.Midland outside the Midland

Atlanta, Georgia has been characterized by a massive movement of non-Southerners into the area during the 1990s, leading the city to becoming hugely mixed in terms of dialect.

Charleston, South Carolina is an area where, today, most speakers have clearly conformed to a Midland regional accent, rather than any Southern accent. Charleston was once home to its own very locally-unique accent that encompassed elements of older British English while resisting Southern regional accent trends, perhaps with additional linguistic influence from

Central and South Florida show no evidence of any type of /aɪ/ glide deletion, Central Florida shows a pin–pen merger, and South Florida does not. Otherwise, Central and South Florida easily fit under the definition of the Midland dialect, including the cot-caught merger being transitional. In

Mid-Atlantic States

The cities of the

According to linguist Barbara Johnstone, migration patterns and geography affected the Philadelphia dialect's development, which was especially influenced by immigrants from Northern England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.[59]

South

The Southern United States is often dialectally identified as "The South," as in ANAE. There is still great variation between sub-regions in the South (see

Inland South and Texas South

The ANAE identifies two important, especially advanced subsets of the South in terms of their leading the Southern Vowel Shift (detailed above): the "Inland South" located in the southern half of Appalachia and the "Texas South," which only covers the north-central region of Texas (Dallas), Odessa, and Lubbock, but not Abilene, El Paso, or southern Texas (which have accents more like the Midland region). One Texan distinction from the rest of the South is that all Texan accents have been reported as showing a pure, non-gliding /ɔ/ vowel,[51] and the identified "Texas South" accent, specifically, is at a transitional stage of the cot-caught merger; the "Inland South" accent of Appalachia, however, firmly resists the merger. Pronunciations of the Southern dialect in Texas may also show notable influence derived from an early Spanish-speaking population or from German immigrants.

Marginal Southeast

The following Southeastern super-regional locations fit cleanly into none of the aforementioned subsets of the Southeast, and may even be marginal-at-best members of the super-region itself:

Chesapeake and the Outer Banks (North Carolina) islands are enclaves of a traditional "

New Orleans, Louisiana has been home to a type of accent with parallels to the New York City accent reported for over a century.[

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, according to the ANAE's research, is not quite a member of the Midland dialect region.[60] Rather, its features seem to be a blend of the Western and Midland dialects. The overview of ANAE's studied features for Oklahoma City speakers include a conservative /aɪ/, conservative /oʊ/, transitional cot-caught merger, and variable pin–pen merger.

Savannah, Georgia once had a local accent that is now "giving way to regional patterns" of the Midland.[60] According to the ANAE, there is much transition in Savannah, and the following features are reported as inconsistent or highly variable in the city: the Southern phenomenon of /aɪ/ being monophthongized, non-rhoticity, /oʊ/ fronting, the cot–caught merger, the pin–pen merger, and conservative /aʊ/ (which is otherwise rarely if ever reported in either the South or the Midland).

St. Louis, Missouri is historically one among several (North) Midland cities, but it is largely considered by ANAE to classify under blends of

Western Pennsylvania

The dialect of the

See also

- Accent (sociolinguistics)

- American English

- American English regional vocabulary

- Boontling

- California English

- Canadian English

- Chicano English

- English in New Mexico

- Hawaiian Pidgin

- Pacific Northwest English

References

Notes

- father–bother merger is the pronunciation of /ɒ/ (as in cot, lot, bother, etc.) the same as /ɑ/ (as in spa, haha, Ma), causing words like con and Kahn and like sob and Saab to sound identical, with the vowel usually realized in the back or middle of the mouth as [ɑ~ɑ̈]. Finally, most of the U.S. participates in a continuous nasal system of the "short a" vowel (in cat, trap, bath, etc.), causing /æ/ to be pronounced with the tongue raised and with a glide quality (typically sounding like [ɛə]) particularly when before a nasal consonant; thus, mad is [mæd], but man is more like [mɛən].

- ^ The only notable exceptions of the South being a subset of the "Southeastern super-region" are two Southern metropolitan areas, described as such because they participate in Stage 1 of the Southern Vowel Shift, but lack the other defining Southeastern features: Savannah, Georgia and Amarillo, Texas.

Citations

- ^ "Why Victoria's English is nearly gone".

- ^ Freeman, Valerie (2014). "Bag, beg, bagel: Prevelar raising and merger in Pacific Northwest English" (PDF). University of Washington Working Papers in Linguistics. Retrieved 22 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:168)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 56

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 235

- ^ a b c d Wagner, S. E.; Mason, A.; Nesbitt, M.; Pevan, E.; Savage, M. (2016). "Reversal and re-organization of the Northern Cities Shift in Michigan" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 22.2: Selected Papers from NWAV 44.

- ^ a b c Driscoll, Anna; Lape, Emma (2015). "Reversal of the Northern Cities Shift in Syracuse, New York". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 21 (2).

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:123–4)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:48)

- ^ a b c Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:182)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:54, 238)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (267)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:127, 254)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:133)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:148)

- ^ a b c d Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:141)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:135)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:237)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:271–2)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:130)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:125)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:124)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:229)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:230)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:231)

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:217)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:223)

- ^ Boberg, Charles (2004). Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (ed.). A Handbook of Varieties of English Volume 1: Phonology. De Gruyter. p. 359.

- ^ Boberg, Charles (2004). Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (ed.). A Handbook of Varieties of English Volume 1: Phonology. De Gruyter. p. 361.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:221)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:107)

- ^ Hedges, Stephanie Nicole (2017). "A Latent Class Analysis of American English Dialects" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 6480. Brigham Young University. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6480

- ^ Wells (1982:10)

- ^ Van Riper (2014:123)

- ^ Martinet, Andre 1955. Economie des changements phonetiques. Berne: Francke.

- ^ Labov et al. 2006; Charles Boberg, "The Canadian Shift in Montreal"; Robert Hagiwara. "Vowel production in Winnipeg"; Rebecca V. Roeder and Lidia Jarmasz. "The Canadian Shift in Toronto."

- ^ Swan, Julia Thomas (2021-01-01). "Same PRICE Different HOUSE". Swan.

- ^ Esling, John H. and Henry J. Warkentyne (1993). "Retracting of /æ/ in Vancouver English."

- ^ Swan, Julia Thomas. "Swan Third Dialect Shift-LSA-2018".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Conn, Jeff (2002). An investigation into the western dialect of Portland Oregon. Paper presented at NWAV 31, Stanford, California. Archived from the original on 2015-11-21.

- ^ Penny Eckert, California vowels. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:68)

- St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:131, 139)

- ^ a b c Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137)

- ^ Southard, Bruce. "Speech Patterns". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:263)

- ^ Thomas (2006:14)

- ^ Thomas (2006:9)

- ^ a b c Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:61)

- ^ Thomas, 2006, p. 16

- ^ Thomas (2006:16)

- ^ Thomas (2006:15)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:260–1)

- ^ "Miami Accents: Why Locals Embrace That Heavy "L" Or Not". WLRN (WLRN-TV and WLRN-FM). 27 August 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- Sun-Sentinel.com. June 13, 2004. Archived from the originalon 2012-08-20. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (262)

- ^ Malady, Matthew J.X. (2014-04-29). "Where Yinz At; Why Pennsylvania is the most linguistically rich state in the country". The Slate Group. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:304)

- ^ Wolfram & Ward (2006:128)

Bibliography

- ISBN 3-11-016746-8

- Shitara, Yuko (1993). "A survey of American pronunciation preferences". Speech Hearing and Language. 7: 201–32.

- The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States (4th ed.). New York: Knopf. ("Mencken, H.L. 1921. The American Language". Bartleby.com. Retrieved February 28, 2017.)

- Rainey, Virginia (2004). Insiders' Guide: Salt Lake City (4 ed.). The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0-7627-2836-1.

- "Brigham Young University Linguistics Department Research Teams". Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- "BYU "Utah English" Research Team's Homepage".

- "Utahnics", segment on National Public RadioFebruary 16, 1997.

- S2CID 247196050.

- Dailey-O'Cain, J. (1997). "Canadian raising in a midwestern U.S. city". Language Variation and Change. 9 (1): 107–120. S2CID 146637083.

- .

- ISBN 0-631-17916-X.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCarthy, John (1993). "A case of surface constraint violation". S2CID 14047772.

- Metcalf, Allan A. (2000). How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- The Speech Accent Archive. George Mason University. 22 September 2004.

- Van Riper, William (2014). "General American: An Ambiguity". In Harold Allen; Michael Linn (eds.). Dialect and Language Variation. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4832-9476-6. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Walsh, M (February 28, 1995). Vermont Accent: Endangered Species?. Burlington Free Press. Archived from the original on 2009-07-25. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- Wolfram, Walt; Ward, Ben, eds. (2006). American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.