Ranjit Singh

| Ranjit Singh | |

|---|---|

| Maharaja of Punjab Maharaja of Lahore Sher-e-Punjab (Lion of Punjab) Sher-e-Hind (Lion of India) Sarkar-i-Wallah (Head of Government) Maharani Datar Kaur Sukerchakia | |

| Father | Sardar Maha Singh |

| Mother | Raj Kaur |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Signature (handprint) |  |

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839),

Prior to his rise, the Punjab region had numerous warring

Ranjit Singh's reign introduced reforms, modernisation, investment into infrastructure and general prosperity.

Early years

Ranjit Singh was born in a

Ranjit Singh contracted smallpox as an infant, which resulted in the loss of sight in his left eye and a pockmarked face.[5] He was short in stature, never schooled, and did not learn to read or write anything beyond the Gurmukhi alphabet.[20] However, he was trained at home in horse riding, musketry and other martial arts.[5]

At age 12, his father died.[21] He then inherited his father's Sukerchakia Misl estates and was raised by his mother Raj Kaur, who, along with Lakhpat Rai, also managed the estates.[5] The first attempt on his life was made when he was 13, by Hashmat Khan, but Ranjit Singh prevailed and killed the assailant instead.[22] At age 18, his mother died and Lakhpat Rai was assassinated, and thereon he was helped by his mother-in-law from his first marriage.[23]

Personal life

Wives

In 1789, Ranjit Singh married his first wife

His second marriage was to,

Ratan Kaur and Daya Kaur were wives of Sahib Singh Bhangi of Gujrat (a misl north of Lahore, not to be confused the state of Gujarat).[44] After Sahib Singh's death, Ranjit Singh took them under his protection in 1811 by marrying them via the rite of chādar andāzī, in which a cloth sheet was unfurled over each of their heads. The same with Roop Kaur, Gulab Kaur, Saman Kaur, and Lakshmi Kaur, looked after Duleep Singh when his mother Jind Kaur was exiled. Ratan Kaur had a son Multana Singh in 1819, and Daya Kaur had two sons Kashmira Singh and Pashaura Singh in 1821.[45][46]

His other wives included, Mehtab Devi of Kangara also called Guddan or Katochan and Raj Banso, daughters of Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra.

He was also married to Rani Har Devi of Atalgarh, Rani Aso Sircar and Rani Jag Deo According to the diaries, that Duleep Singh kept towards the end of his life, that these women presented the Maharaja with four daughters. Dr. Priya Atwal notes that the daughters could be adopted.[24] Ranjit Singh was also married to Jind Bani or Jind Kulan, daughter of Muhammad Pathan from Mankera and Gul Bano, daughter of Malik Akhtar from Amritsar.

Ranjit Singh married many times, in various ceremonies, and had twenty wives.

Issues

Issues of Ranjit Singh

- Kharak Singh

- Ishar Singh

- Rattan Singh

- Sher Singh

- Tara Singh

- Fateh Singh[56]

- Multana Singh

- Kashmira Singh

- Peshaura Singh

- Maharaja Duleep Singh

Punishment by the Akal Takht

In 1802, Ranjit Singh married

Issue

- Kharak Singh (22 February 1801 – 5 November 1840) was the eldest and the favorite of Ranjit Singh from his second and favorite wife, Datar Kaur.[59] He succeeded his father as the Maharaja.

- Ishar Singh son of his first wife, Mehtab Kaur. This prince died in infancy in 1805.

- Rattan Singh (1805–1845) was born to Maharani Datar Kaur.[60][61] He was granted the Jagatpur Bajaj estate as his jagir.

- Sher Singh (4 December 1807 – 15 September 1843) was elder of the twins of Mehtab Kaur. He briefly became the Maharaja of the Sikh Empire.

- Tara Singh (4 December 1807 – 1859) younger of the twins born of Mehtab Kaur.

- Multana Singh (1819–1846) son of Ratan Kaur.

- Kashmira Singh (1821–1844) son of Daya Kaur.

- Pashaura Singh (1821–1845) younger son of Daya Kaur.

- Duleep Singh (4 September 1838 – 22 October 1893), the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire. Ranji Singh's youngest son, the only child of Jind Kaur.

According to the pedigree table and Duleep Singh's diaries that he kept towards the end of his life mention another son Fateh Singh was born to Mai Nakain, who died in infancy.[35] According to Henry Edward only Datar Kaur and Jind Kaur's sons are Ranjit Singh's biological sons.[62][63]

It is said that Ishar Singh was not the biological son of Mehtab Kaur and Ranjit Singh, but only procured by Mehtab Kaur and presented to Ranjit Singh who accepted him as his son.[64] Tara Singh and Sher Singh had similar rumors, it is said that Sher Singh was the son of a chintz weaver, Nahala and Tara Singh was the son of Manki, a servant in the household of Sada Kaur. Henry Edward Fane, the nephew and aide-de-camp to the Commander-in-Chief, India, General Sir Henry Fane, who spent several days in Ranjit Singh's company, reported, "Though reported to be the Maharaja's son, Sher Singh's father has never thoroughly acknowledged him, though his mother always insisted on his being so. A brother of Sher, Tara Singh by the same mother, has been even worse treated than himself, not being permitted to appear at court, and no office given him, either of profit or honour." Five Years in India, Volume 1, Henry Edward Fane, London, 1842[full citation needed][page needed]

Multana Singh, Kashmira Singh and Pashaura Singh were sons of the two widows of Sahib Singh, Daya Kaur and Ratan Kaur, that Ranjit Singh took under his protection and married. These sons, are said to be, not biologically born to the queens and only procured and later presented to and accepted by Ranjit Singh as his sons.[65]

Establishment of the Sikh Empire

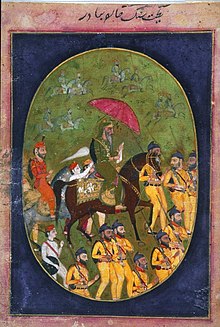

circa 1816–29

Historical context

After the death of

By the second half of the 18th century, the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent (now Pakistan and parts of north India) were a collection of fourteen small warring regions.[6] Of the fourteen, twelve were Sikh-controlled misls (confederacies), one named Kasur (near Lahore) was Muslim controlled, and one in the southeast was led by an Englishman named George Thomas.[6] This region constituted the fertile and productive valleys of the five rivers – Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Bias and Sutlej.[44] The Sikh misls were all under the control of the Khalsa fraternity of Sikh warriors, but they were not united and constantly warred with each other over revenue collection, disagreements, and local priorities; however, in the event of external invasion such as from the Muslim armies of Ahmed Shah Abdali from Afghanistan, they would usually unite.[6]

Towards the end of 18th century, the five most powerful misls were those of Sukkarchakkia, Kanhayas, Nakkais, Ahluwalias and Bhangi Sikhs.[6][21] Ranjit Singh belonged to the first, and through marriage had a reliable alliance with Kanhayas and Nakkais.[6] Among the smaller misls, some such as the Phulkias misl had switched loyalties in the late 18th century and supported the Afghan army invasion against their Khalsa brethren.[6] The Kasur region, ruled by Muslim, always supported the Afghan invasion forces and joined them in plundering Sikh misls during the war.[6]

Military campaigns

Rise to fame, early conquests

Ranjit Singh's fame grew in 1797, at age 17, when the Afghan Muslim ruler Shah Zaman, of the Ahmad Shah

In 1799, Raja Ranjit Singh's army of 25,000 Khalsa, supported by another 25,000 Khalsa led by his mother-in-law Rani Sada Kaur of Kanhaiya misl, in a joint operation attacked the region controlled by Bhangi Sikhs centered around Lahore. The rulers escaped, marking Lahore as the first major conquest of Ranjit Singh.[6][67] The Sufi Muslim and Hindu population of Lahore welcomed the rule of Ranjit Singh.[5] In 1800, the ruler of Jammu region ceded control of his region to Ranjit Singh.[68]

In 1801, Ranjit Singh proclaimed himself as the "Maharaja of Punjab", and agreed to a formal investiture ceremony, which was carried out by Baba Sahib Singh Bedi – a descendant of Guru Nanak. On the day of his coronation, prayers were performed across mosques, temples and gurudwaras in his territories for his long life.[69] Ranjit Singh called his rule as "Sarkar Khalsa", and his court as "Darbar Khalsa". He ordered new coins to be issued in the name of Guru Nanak named the "NanakShahi" ("of the Emperor Nanak").[5][70][71]

Expansion

In 1802, Ranjit Singh, aged 22, took Amritsar from the Bhangi Sikh misl, paid homage at the

On 1 January 1806, Ranjit Singh signed a treaty with the British officials of the East India Company, in which he agreed that his Sikh forces would not attempt to expand south of the Sutlej river, and the Company agreed that it would not attempt to militarily cross the Sutlej river into the Sikh territory.[73]

In 1807, Ranjit Singh's forces attacked the Muslim ruled Kasur and, after a month of fierce fighting in the

The most significant encounters between the Sikhs in the command of the Maharaja and the Afghans were in 1813, 1823, 1834 and in 1837.

In 1813–14, Ranjit Singh's first attempt to expand into Kashmir was foiled by Afghan forces led by Azim Khan, due to a heavy downpour, the spread of cholera, and poor food supply to his troops.[citation needed]

In 1818, Darbar's forces led by Kharak Singh and Misr Dewan Chand occupied Multan, killing Muzaffar Khan and defeating his forces, leading to the end of Afghan influence in the Punjab.[76]

In July 1818, an army from the Punjab defeated Jabbar Khan, a younger brother of governor of Kashmir Azim Khan, and acquired Kashmir, along with a yearly revenue of Rs seventy lacs. Dewan Moti Ram was appointed governor of Kashmir.[77]

In 1823,

In 1834, Mohammed Azim Khan once again marched towards Peshawar with an army of 25,000 Khattak and Yasufzai tribesmen in the name of jihad, to fight against infidels. The Maharaja defeated the forces. Yar Mohammad was pardoned and was reinvested as governor of Peshawar with an annual revenue of Rs one lac ten thousand to Lahore Darbar.[79]

In 1835, the Afghans and Sikhs met again at the Standoff at the Khyber Pass, however it ended without a battle.[80]

In 1837, the Battle of Jamrud, became the last confrontation between the Sikhs led by him and the Afghans, which displayed the extent of the western boundaries of the Sikh Empire.[81][82]

On 25 November 1838, the two most powerful armies on the Indian subcontinent assembled in a grand review at Ferozepore as Ranjit Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjab brought out the Dal Khalsa to march alongside the sepoy troops of the East India Company and the British troops in India.[83] In 1838, he agreed to a treaty with the British viceroy Lord Auckland to restore Shah Shoja to the Afghan throne in Kabul. In pursuance of this agreement, the British army of the Indus entered Afghanistan from the south, while Ranjit Singh's troops went through the Khyber Pass and took part in the victory parade in Kabul.[4][84]

Geography of the Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire, also known as the Sikh Raj and Sarkar-a-Khalsa,

The geographical reach of the Sikh Empire under Singh included all lands north of Sutlej river, and south of the high valleys of the northwestern Himalayas. The major towns at time included Srinagar, Attock, Peshawar, Bannu, Rawalpindi, Jammu, Gujrat, Sialkot, Kangra, Amritsar, Lahore and Multan.[44][87]

Muslims formed around 70%, Hindus formed around 24%, and Sikhs formed around 6–7% of the total population living in Singh's empire[88]: 2694

Governance

Ranjit Singh allowed men from different religions and races to serve in his army and his government in various positions of authority.

Religious policies

As consistent with many Punjabis of that time, Ranjit Singh was a secular king

He built several gurdwaras, Hindu temples and even mosques, and one in particular was Mai Moran Masjid, built on the behest of his beloved Muslim wife,

Singh's sovereignty was accepted by Afghan and Punjabi Muslims, who fought under his banner against the Afghan forces of Nadir Shah and later of Azim Khan. His court was ecumenical in composition: his prime minister, Dhian Singh, was a Hindu (Dogra); his foreign minister, Fakir Azizuddin, was a Muslim; and his finance minister, Dina Nath, was also a Hindu (Brahmin). Artillery commanders such as Mian Ghausa were also Muslims. There were no forced conversions in his time. His wives Bibi Mohran, Gilbahar Begum retained their faith and so did his Hindu wives. He also employed and surrounded himself with astrologers and soothsayers in his court.[106]

Ranjit Singh had also abolished the gurmata and provided significant patronage to the Udasi and Nirmala sect, leading to their prominence and control of Sikh religious affairs.[111]

Administration

Khalsa Army

The army under Ranjit Singh was not limited to the Sikh community. The soldiers and troop officers included Sikhs, but also included Hindus, Muslims and Europeans.[112] Hindu Brahmins and people of all creeds and castes served his army,[113][114] while the composition in his government also reflected a religious diversity.[112][115] His army included Polish, Russian, Spanish, Prussian and French officers.[11] In 1835, as his relationship with the British warmed up, he hired a British officer named Foulkes.[11]

However, the Khalsa army of Ranjit Singh reflected regional population, and as he grew his army, he dramatically increased the Rajputs and the Sikhs who became the predominant members of his army.[10] In the Doaba region his army was composed of the Jat Sikhs, in Jammu and northern Indian hills it was Hindu Rajputs, while relatively more Muslims served his army in the Jhelum river area closer to Afghanistan than other major Panjab rivers.[116]

Reforms

Ranjit Singh changed and improved the training and organisation of his army. He reorganised responsibility and set performance standards in logistical efficiency in troop deployment,

While Ranjit Singh introduced reforms in terms of training and equipment of his military, he failed to reform the old Jagirs (Ijra) system of Mughal middlemen.[117][118] The Jagirs system of state revenue collection involved certain individuals with political connections or inheritance promising a tribute (nazarana) to the ruler and thereby gaining administrative control over certain villages, with the right to force collect customs, excise and land tax at inconsistent and subjective rates from the peasants and merchants; they would keep a part of collected revenue and deliver the promised tribute value to the state.[117][119][120] These Jagirs maintained independent armed militia to extort taxes from the peasants and merchants, and the militia prone to violence.[117] This system of inconsistent taxation with arbitrary extortion by militia, continued the Mughal tradition of ill treatment of peasants and merchants throughout the Sikh Empire, and is evidenced by the complaints filed to Ranjit Singh by East India Company officials attempting to trade within different parts of the Sikh Empire.[117][118]

According to historical records, states Sunit Singh, Ranjit Singh's reforms focused on military that would allow new conquests, but not towards taxation system to end abuse, nor about introducing uniform laws in his state or improving internal trade and empowering the peasants and merchants.[117][118][119] This failure to reform the Jagirs-based taxation system and economy, in part led to a succession power struggle and a series of threats, internal divisions among Sikhs, major assassinations and coups in the Sikh Empire in the years immediately after the death of Ranjit Singh;[121] an easy annexation of the remains of the Sikh Empire into British India followed, with the colonial officials offering the Jagirs better terms and the right to keep the system intact.[122][123][124]

Infrastructure investments

Ranjit Singh ensured that Panjab manufactured and was self-sufficient in all weapons, equipment and munitions his army needed.[11] His government invested in infrastructure in the 1800s and thereafter, established raw materials mines, cannon foundries, gunpowder and arm factories.[11] Some of these operations were owned by the state, others operated by private Sikh operatives.[11]

However, Ranjit Singh did not make major investments in other infrastructure such as irrigation canals to improve the productivity of land and roads. The prosperity in his Empire, in contrast to the Mughal-Sikh wars era, largely came from the improvement in the security situation, reduction in violence, reopened trade routes and greater freedom to conduct commerce.[125]

Muslim accounts

The mid 19th-century Muslim historians, such as Shahamat Ali who experienced the Sikh Empire first hand, presented a different view on Ranjit Singh's Empire and governance.[126][127] According to Ali, Ranjit Singh's government was despotic, and he was a mean monarch in contrast to the Mughals.[126] The initial momentum for the Empire building in these accounts is stated to be Ranjit Singh led Khalsa army's "insatiable appetite for plunder", their desire for "fresh cities to pillage", and eliminating the Mughal era "revenue intercepting intermediaries between the peasant-cultivator and the treasury".[121]

According to Ishtiaq Ahmed, Ranjit Singh's rule led to further persecution of Muslims in Kashmir, expanding[clarification needed] the previously selective persecution of Shia Muslims and Hindus by Afghan Sunni Muslim rulers between 1752 and 1819 before Kashmir became part of his Sikh Empire.[74] Bikramjit Hasrat describes Ranjit Singh as a "benevolent despot".[128] The Muslim accounts of Ranjit Singh's rule were questioned by Sikh historians of the same era. For example, Ratan Singh Bhangu in 1841 wrote that these accounts were not accurate, and according to Anne Murphy, he remarked, "when would a Musalman praise the Sikhs?"[129] In contrast, the colonial era British military officer Hugh Pearse in 1898 criticised Ranjit Singh's rule, as one founded on "violence, treachery and blood".[130] Sohan Seetal disagrees with this account and states that Ranjit Singh had encouraged his army to respond with a "tit for tat" against the enemy, violence for violence, blood for blood, plunder for plunder.[131]

Decline

Singh made his empire and the Sikhs a strong political force, for which he is deeply admired and revered in Sikhism. After his death, empire failed to establish a lasting structure for Sikh government or stable succession, and the Sikh Empire began to decline. The British and Sikh Empire fought two

Clive Dewey has argued that the decline of the empire after Singh's death owes much to the jagir-based economic and taxation system which he inherited from the Mughals and retained. After his death, a fight to control the tax spoils emerged, leading to a power struggle among the nobles and his family from different wives. This struggle ended with a rapid series of palace coups and assassinations of his descendants, and eventually the annexation of the Sikh Empire by the British.[121]

Death and legacy

Death

In the 1830s, Ranjit Singh suffered from numerous health complications as well as a stroke, which some historical records attribute to alcoholism and a failing liver.[44][134] According to the chronicles of Ranjit Singh's court historians and the Europeans who visited him, Ranjit Singh took to alcohol and opium, habits that intensified in the later decades of his life.[135][136][137] However, he neither smoked nor ate beef,[5] and required all officials in his court, regardless of their religion, to adhere to these restrictions as part of their employment contract.[136] He died in his sleep on 27 June 1839.[48] Four of his Hindu wives- Mehtab Devi (Guddan Sahiba), daughter of Raja Sansar Chand, Rani Har Devi, the daughter of Chaudhri Ram, a Saleria rajput, Rani Raj Devi, daughter of Padma Rajput and Rani Rajno Kanwar, daughter of Sand Bhari along with seven Hindu concubines with royal titles committed sati by voluntarily placing themselves onto his funeral pyre as an act of devotion.[48][138]

Singh is remembered for uniting Sikhs and founding the prosperous Sikh Empire. He is also remembered for his conquests and building a well-trained, self-sufficient Khalsa army to protect the empire.

Gurdwaras

Perhaps Singh's most lasting legacy was the restoration and expansion of the Harmandir Sahib, the most revered Gurudwara of the Sikhs, which is now known popularly as the "Golden Temple".

Memorials and museums

- Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in Lahore, Pakistan, marks the place where Singh was cremated, and four of his queens and seven concubines committed sati.[144][145]

- On 20 August 2003, a 22-foot-tall bronze statue of Singh was installed in the Parliament of India.[146]

- A museum at Ram Bagh Palace in Amritsar contains objects related to Singh, including arms and armour, paintings, coins, manuscripts, and jewellery. Singh had spent much time at the palace in which it is situated, where a garden was laid out in 1818.[147]

- On 27 June 2019, a nine-feet bronze statue of Singh was unveiled at the Haveli Maharani Jindan, Lahore Fort at his 180th death anniversary.[148] It has been vandalised several times since, specifically by members of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan.[149][150]

Crafts

In 1783, Ranjit Singh established a crafts colony of Thatheras near Amritsar and encouraged skilled metal crafters from Kashmir to settle in Jandiala Guru.[151] In the year 2014, this traditional craft of making brass and copper products got enlisted on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO.[152] The Government of Punjab is now working under Project Virasat to revive this craft.[153]

Recognition

In 2020, Ranjit Singh was named as "Greatest Leader of All Time" in a poll conducted by 'BBC World Histories Magazine'.[154][155][156]

In popular culture

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a documentary film directed by Prem Prakash covers his rise to power and his reign. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.[157]

- In 2010, a TV series titled Maharaja Ranjit Singh aired on DD National based on his life which was produced by Raj Babbar's Babbar Films Private Limited. He was portrayed by Ejlal Ali Khan

- Maharaja: The Story of Ranjit Singh (2010) is an Indian Punjabi-language animated film directed by Amarjit Virdi.[158]

- A teenage Ranjit was portrayed by Damanpreet Singh in the 2017 TV series titled Contiloe Entertainment.

See also

- Baradari of Ranjit Singh

- History of Punjab

- Charat Singh

- Hari Singh Nalwa

- List of generals of Ranjit Singh

- Koh-i-Noor

- Battle of Balakot[159][160][161]

Notes

References

- ^ https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/hindi-english/%E0%A4%B8%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B0#:~:text=%2Fsarak%C4%81ra%2F,are%20responsible%20for%20governing%20it.

- ^ A history of the Sikhs by Kushwant Singh, Volume I (p. 195)

- ISBN 978-81-7625-738-1.

- ^ a b Ranjit Singh Encyclopædia Britannica, Khushwant Singh (2015)

- ^ ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b Grewal, J. S. (1990). "Chapter 6: The Sikh empire (1799–1849)". The Sikh empire (1799–1849). The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ a b c d Teja Singh; Sita Ram Kohli (1986). Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 65–68.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ISBN 978-1-134-63136-0.

- OCLC 557676461.

Even before the birth of Ranjit Singh, cordial relations had been established between the Sukarchakia Misal and the Phulkian House of Jind. ... the two Sikh Jat chiefships had cultivated intimate relationship with each other by means of a matrimonial alliance. Maha Singh, the son of the founder of Sukarchakia Misal, Charat Singh, was married to Raj Kaur, the daughter of the founder of the Jind State, Gajpat Singh. The marriage was celebrated in 1774 at Badrukhan, then capital of Jind1, with pomp and grandeur worthy of the two chiefships. ... Ranjit Singh was the offspring of this wedlock.

- ISBN 978-0720613230.

- ISBN 978-0810863446.

Sikhs remember Maharaja Ranjit Singh with respect and affection as their greatest ruler. Ranjit Singh was a Sansi and this identity has led some to claim that his caste affiliation was with the low-caste Sansi tribe of the same name. A much more likely theory is that he belonged to the Jat got that used the same name. The Sandhanvalias belonged to the same got.

- ISBN 978-1136517860.

Ibbetson and Rose and later, Bedi, had clarified that the Sansis should not be confused with a Jat (Jutt) clan named Sansi to which perhaps Maharaja Ranjit Singh also belonged.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-754831-8.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ISBN 978-1-78738-308-1.

- OCLC 52691326.

- ^ "Mahanian Koharan Tehsil .Amritsar District .AmritsarState .Punjab" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (1 May 2015). "Descendants of Maharaja Ranjit Singh stakes claim on Gobindgarh Fort". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (18 August 2021). "Seventh generation descendent of Maharaja Ranjit Singh writes to Imran". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- S2CID 236800828.

- ^ Journal of Sikh Studies. Department of Guru Nanak Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University. 2001.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-756694-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78673-095-4

- ISBN 978-9386834195.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ Khushwant Singh (1962). Ranjit Singh Maharajah Of The Punjab 1780–1839. Servants of Knowledge. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ^ Fakir, Syed Waheeduddin; Vaḥīduddīn, Faqīr Sayyid (1965). The Real Ranjit Singh. Lion Art Press.

- OCLC 499465766.

- OCLC 841311234.

- ISBN 978-0-8364-1504-9.

- OCLC 163394684.

- ^ a b c d Vincent Arthur Smith (1920). The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911. Oxford University Press. pp. 690–693.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-100-6.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-204-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-63286-081-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel Henry (1865). The Panjab Chiefs: Historical and Biographical Notices of the Principal Families in the Territories Under the Panjab Government. T.C. McCarthy.

- ^ Lal Suri, Lala Sohan. Umdat Ul Tawarikh.

- OCLC 49618584.

- ^ Atwal, Priya (2020). Royals and Rebels.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-7017-410-3.

- ^ Vaḥīduddīn, Faqīr Sayyid (1965). The Real Ranjit Singh. Lion Art Press.

- ISBN 978-1-78673-095-4

- ^ a b Singh, Kartar (1975). Stories from Sikh History: Book–VII. New Delhi: Hemkunt Press. p. 160.

- ISBN 978-1-250-06263-5.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (1 May 2015). "Descendants of Maharaja Ranjit Singh stakes claim on Gobindgarh Fort". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (18 August 2021). "Seventh generation descendent of Maharaja Ranjit Singh writes to Imran". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Fane, Henry Edward (1842). Five Years in India, Volume 1, Chapter VII. Henry Colburn. p. 120. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Chapter VII". Lady Login's Recollections. Smith, Elder & Co, London. 1916. p. 85. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- OCLC 777874299.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel Henry (1898). Ranjit Síngh and the Sikh Barrier Between Our Growing Empire and Central Asia. Clarendon Press.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84885-321-8.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ISBN 978-1-63286-081-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85567-578-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-1789140101.

- ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Joseph Davey Cunningham (1843). A History of the Sikhs, from the Origin of the Nation to the Battles of the Sutlej. p. 9.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-58710-1.

- ^ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 109–110.

- ISBN 978-1615302017.

- ISBN 978-8-1-7380-204-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ^ Marshall 2005, p. 116.

- JSTOR 4413731.

- ISBN 978-81-7017-410-3.

- ISBN 978-1615301492.

- ISBN 978-1-108-02872-1.

- Matthew Atmore Sherring (1868). The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Trübner & co. p. 51.

- ISBN 978-0-549-52839-5.

- ISBN 8170172446.

- OCLC 2140005.

- ^ "The Tribune – Windows – This Above All". www.tribuneindia.com.

- ISBN 978-0300222906.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ISBN 8121505402.

- ISBN 81-7017-244-6.

- ISBN 978-0143031666. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

In Lahore, just as he had grasped its historic citadel and put it to his own hardy use or desecrated the Badshahi Mosque and converted it into a functional ammuniation store...

- ^ ISBN 978-9690006943.

- ^ Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. Printed at the New Imperial Press. p. 125.

- ^ Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. Printed at the New Imperial Press. pp. 221–223, 339.

- ^ "Maryam Zamani Mosque". Journal of Central Asia. 19. Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University: 97. 1996.

- ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-1136451089.

- ISBN 978-0791414255.

- ISBN 978-0802082459.

- ISBN 978-0-231-51980-9.

As Khalsa Sikhs became more settled and as Ranjit Singh's rule became more autocratic, the Gurumata was effectively abolished, thereby ensuring that the doctrine of the Guru Panth would lose its efficacy. At the same time, however, Ranjit Singh continued to patronize Udasi and Nirmala ashrams. The single most important result of this was the more pronounced diffusion of Vedic and Puranic concepts into the existing Sikh interpretive frameworks

- ^ [107][108][109][110]

- ^ a b Teja Singh; Sita Ram Kohli (1986). Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 56, 67.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-143-06543-2.

- ^ Teja Singh; Sita Ram Kohli (1986). Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 83–85.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-876924-61-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0.

- ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-349-11556-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9257-1.

- ISBN 978-1-349-11558-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-66360-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-521939-5.

- OCLC 6303625.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991629-0.

- ^ Gardner, Alexander (1898). "Chapter XII". Memoirs of Alexander Gardner – Colonel of Artillery in the Service of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. William Blackwood & Sons. p. 211.

- OCLC 6917931. (note: the original book has 667 pages; the open access version of the same book released by Lahore Publishers on archive.com has deleted about 500 pages of this book; see the original)

- ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- ISBN 978-81-7017-410-3.

- ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4668-0379-4.

- ISBN 978-1-78327-129-0.

- ISBN 978-8120803244.

- ISBN 978-1-84176-777-2.

- ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 2001, 2nd ed.

- ISBN 978-1-108-04642-8.

- ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- ^ Teja, Charanjit Singh (29 March 2021). "Guru's legacy muralled on wall in Gurdwara Baba Attal Rai". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "'Sati' choice before Maharaja Ranjit's Ranis". Tribuneindia News Service.

- ^ "Nishan Sahib Khanda Sikh Symbols Sikh Museum History Heritage Sikhs". www.sikhmuseum.com.

- ^ Singh, Ranjit (20 August 2003). "Parliament to get six more portraits, two statues". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Maharaja Ranjit Singh Museum, Amritsar". Punjab Museums. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Statue of Ranjit Singh unveiled on his 180th death anniversary". 28 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Statue of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Lahore vandalised by a man because Singh had converted a mosque into a horse stable". 12 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Kumar, Anil. "Maharaja Ranjit Singh's statue in Pakistan vandalised by activist of banned far-right outfit". India Today. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Traditional brass and copper craft of utensil making from Punjab gets inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, UNESCO, 2014". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "UNESCO – Traditional brass and copper craft of utensil making among the Thatheras of Jandiala Guru, Punjab, India". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Rana, Yudhvir (24 June 2018). "Jandiala utensils: Age-old craft of thatheras to get new life". The Times of India – Chandigarh News. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Maharaja Ranjit Singh named greatest world leader in BBC Poll". The Economic Times.

- ^ "Sikh warrior Maharaja Ranjit Singh beats Winston Churchill as the greatest leader of all time".

- ^ "Sikh warrior voted greatest leader of all time in BBC poll". 5 March 2020.

- ^ "MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH | Films Division". filmsdivision.org. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Maharaja: The Story of Ranjit Singh". Netflix.

- ^ "Shah Ismail Shaheed". Rekhta.

- ^ Shaheed, Shah Ismail. "Strengthening the Faith – English – Shah Ismail Shaheed". IslamHouse.com.

- ^ Profile of Dehlvi on books.google.com website Retrieved 16 August 2018

Bibliography

- Jacques, Tony (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5.

- Heath, Ian (2005). The Sikh Army 1799–1849. Oxford: Osprey Publishing (UK). ISBN 1-84176-777-8.

- Lafont, Jean-Marie Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford: ISBN 0-19-566111-7

- Marshall, Julie G. (2005), Britain and Tibet 1765–1947: a select annotated bibliography of British relations with Tibet and the Himalayan states including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan (Revised and Updated to 2003 ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-33647-5

- Sandhawalia, Preminder Singh Noblemen and Kinsmen: history of a Sikh family. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1999 ISBN 81-215-0914-9

- Waheeduddin, Fakir Syed The Real Ranjit Singh; 2nd ed. Patiala: Punjabi University, 1981 ISBN 81-7380-778-7(First ed. published 1965 Pakistan).

- Griffin, Sir Lepel Henry (1909). Chiefs and Families of Note in the Punjab. The National Archives: Civil and Military Gazette Press. ISBN 978-8175365155. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

Further reading

- Umdat Ut Tawarikh by Sohan Lal Suri, Published by Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar .

- The Real Ranjit Singh by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 2001, 2nd ed. First ed. published 1965 Pakistan.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: First Death Centenary Memorial, by St. Nihal Singh. Published by Languages Dept., Punjab, 1970.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his times, by J. S. Grewal, Indu Banga. Published by Dept. of History, Guru Nanak Dev University, 1980.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Harbans Singh. Published by Sterling, 1980.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by K. K. Khullar. Published by Hem Publishers, 1980.

- The reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh: structure of power, economy and society, by J. S. Grewal. Published by Punjab Historical Studies Dept., Punjabi University, 1981.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, as patron of the arts, by Ranjit Singh. Published by Marg Publications, 1981.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Politics, Society, and Economy, by Fauja Singh, A. C. Arora. Published by Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, 1984.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his Times, by Bhagat Singh. Published by Sehgal Publishers Service, 1990. ISBN 81-85477-01-9.

- History of the Punjab: Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Shri Ram Bakshi. Published by Anmol Publications, 1991.

- The Historical Study of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Times, by Kirpal Singh. Published by National Book Shop, 1994. ISBN 81-7116-163-4.

- An Eyewitness account of the fall of Sikh empire: memories of Alexander Gardner, by Alexander Haughton Campbell Gardner, Baldev Singh Baddan, Hugh Wodehouse Pearse. Published by National Book Shop, 1999. ISBN 81-7116-231-2.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms, by Kartar Singh Duggal. Published by Abhinav Publications, 2001. ISBN 81-7017-410-4.

- Fauj-i-khas Maharaja Ranjit Singh and His French Officers, by Jean Marie Lafont. Published by Guru Nanak Dev University, 2002. ISBN 81-7770-048-0.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Mohinder Singh, Rishi Singh, Sondeep Shankar, National Institute of Panjab Studies (India). Published by UBS Publishers' Distributors with National Institute of Panjab Studies, 2002. ISBN 81-7476-372-4,.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers, by Jean Marie Lafont. Published by Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-566111-7.

- The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbar, by Amarinder Singh. Published by Roli Books, 2010.

- Glory of Sikhism, by R. M. Chopra, Sanbun Publishers, 2001. Chapter on "Sher-e-Punjab Maharaja Ranjit Singh".

- Ranjit Singh, Maharajah of the Punjab, by Khushwant Singh

External links

Quotations related to Ranjit Singh at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Ranjit Singh at Wikiquote Media related to Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab at Wikimedia Commons- Detailed article on Ranjit Singh's Army

Runjeet-Singh, and his Suwarree of Seiks., painted by W Harvey and engraved by G Presbury for Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1838, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

Runjeet-Singh, and his Suwarree of Seiks., painted by W Harvey and engraved by G Presbury for Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1838, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

- Biographies

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 892.