Space Race

- Afrikaans

- العربية

- Asturianu

- Azərbaycanca

- تۆرکجه

- বাংলা

- 閩南語 / Bân-lâm-gú

- Башҡортса

- Български

- Bosanski

- Català

- Čeština

- Cymraeg

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Galego

- 한국어

- Hrvatski

- Ido

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Bahasa Melayu

- မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Nederlands

- नेपाली

- 日本語

- Norsk bokmål

- ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

- پنجابی

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Rumantsch

- Русский

- Seeltersk

- සිංහල

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- کوردی

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Tagalog

- தமிழ்

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- اردو

- Tiếng Việt

- 吴语

- ייִדיש

- 粵語

- 中文

| Part of a series on | ||

| Spaceflight | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

|

||

|

||

|

Spaceflight types |

||

|

List of space organizations |

||

|

| ||

The Space Race (Russian: космическая гонка, romanized: kosmicheskaya gonka, IPA:

Public interest in space travel originated in the 1951 publication of a Soviet youth magazine and was promptly picked up by US magazines.[5] The competition began on July 30, 1955, when the United States announced its intent to launch artificial satellites for the International Geophysical Year. Four days later, the Soviet Union responded by declaring they would also launch a satellite "in the near future". The launching of satellites was enabled by developments in ballistic missile capabilities since the end of World War II.[6] The competition gained Western public attention with the "Sputnik crisis", when the USSR achieved the first successful satellite launch, Sputnik 1, on October 4, 1957. It gained momentum when the USSR sent the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space with the orbital flight of Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. These were followed by a string of other firsts achieved by the Soviets over the next few years.[7][8][9]

Gagarin's flight led US president

A period of

Origins

Although Germans,

Public interest in space flight was first aroused in October 1951 when the Soviet rocketry engineer Mikhail Tikhonravov published "Flight to the Moon" in the newspaper Pionerskaya pravda for young readers. He described a two-person interplanetary spaceship of the future and the industrial and technological processes required to create it. He ended the short article with a clear forecast of the future: "We do not have long to wait. We can assume that the bold dream of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky will be realized within the next 10 to 15 years."[20] From March 1952 to April 1954, the US Collier's magazine reacted with a series of seven articles Man Will Conquer Space Soon! detailing Wernher von Braun's plans for crewed spaceflight. In March 1955, Disneyland's animated episode "Man in Space" which was broadcast on US television with an audience of about 40 million people, eventually fired the public enthusiasm for space travel and raised government interest, both in the US and USSR.

Missile race

Soon after the end of World War II, the two former allies became engaged in a state of political conflict and military tension known as the Cold War (1947–1991), which polarized Europe between the Soviet Union's satellite states (often referred to as the Eastern Bloc) and the states of the Western world allied with the U.S.[21]

In August 1949, the Soviet Union became the second nuclear power after the United States with the successful

ICBMs presented the ability to strike targets on the other side of the globe in a very short amount of time and in a manner which was impervious to air interception such as bombers might have been. The value which ICBMs presented in a nuclear standoff were very substantial, and this fact greatly accelerated efforts to develop rocket and rocket interception technology.[25]

Soviet rocket development

The first Soviet development of artillery rockets was in 1921 when the Soviet military sanctioned the Gas Dynamics Laboratory, a small research laboratory to explore solid-fuel rockets, led by Nikolai Tikhomirov, who had begun studying solid and liquid-fueled rockets in 1894, and obtained a patent in 1915 for "self-propelled aerial and water-surface mines.[26][27] The first test-firing of a solid fuel rocket was carried out in 1928.[28]

Further development was carried out in the 1930s by the

In 1945 the Soviets captured several key

Design work began in 1953 on the R-7 Semyorka with the requirement for a missile with a launch mass of 170 to 200 tons, range of 8,500 km and carrying a 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) nuclear warhead, powerful enough to launch a nuclear warhead against the United States. In late 1953 the warhead's mass was increased to 5.5 to 6 tons to accommodate the then planned theromonuclear bomb.[45][46] The R-7 was designed in a two-stage configuration, with four boosters that would jettison when empty.[47] On the 21 August 1957 the R-7 flew 6,000 km (3,700 mi), and became the worlds's first intercontinental ballistic missile.[48][46] Two months later the R-7 launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit, and became the basis for the R-7 family which includes Sputnik, Luna, Molniya, Vostok, and Voskhod space launchers, as well as later Soyuz variants. Several versions are still in use and it has become the world's most reliable space launcher.[49][50]

American rocket development

Although American rocket pioneer

Each of the United States armed services had its own ICBM development program. The Air Force began ICBM research in 1945 with the

A later variant of the Atlas, the

ICBM capability, satellites, lunar probes (1955–1960)

The period from 1955 to 1960 saw the first artificial satellites put into earth orbit by both the USSR and the US, the first animals sent into orbit, and the first robotic probes to impact and flyby the Moon by the Soviets.

Artificial satellite development

In 1955, with both the United States and the Soviet Union building ballistic missiles that could be used to launch objects into space, the stage was set for nationalistic competition.

Soviet secrecy and obfuscation

The Soviet space program's use of secrecy served as both a tool to prevent the leaking of

The Soviet military maintained control over the space program; Korolev's

US concerns and strategy

Initially, President Eisenhower was worried that a satellite passing above a nation at over 100 kilometers (62 mi) might be seen as violating that nation's airspace.

Sputnik

Korolev received word about von Braun's 1956 Jupiter-C test and, mistakenly thinking it was a satellite mission that failed, expedited plans to get his own satellite in orbit. Since the R-7 was substantially more powerful than any of the US

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Korolev was buoyed by the first successful launches of the R-7 rocket in August and September, which paved the way for the launch of Sputnik.

The first launch took place on Friday, October 4, 1957, at exactly 10:28:34 pm Moscow time, with the R-7 and the now named Sputnik 1 satellite lifting off the launch pad and placing the artificial "moon" into an orbit a few minutes later.[72] This "fellow traveler", as the name is translated in English, was a small, beeping ball, less than two feet in diameter and weighing less than 200 pounds. But the celebrations were muted at the launch control center until the down-range far east tracking station at Kamchatka received the first distinctive beep ... beep ... beep sounds from Sputnik 1's radio transmitters, indicating that it was on its way to completing its first orbit.[72] About 95 minutes after launch, the satellite flew over its launch site, and its radio signals were picked up by the engineers and military personnel at Tyura-Tam: that's when Korolev and his team celebrated the first successful artificial satellite placed into Earth-orbit.[73]

The next satellite sent by the Soviets after Sputnik 1 was Sputnik 2, launched on November 3, 1957, just a month later. This would put the first animal into orbit.[74][75]

US reaction to Sputnik

CIA assessment

At the latest, the successful start of Sputnik 2 with the satellite weighing more than 500 kg proved that the USSR had achieved a leading advantage in rocket technology. The CIA, initially astonished, estimated the launch weight of the rocket at 500 metric tons, requiring an initial thrust exceeding 1,000 tons, and assumed the use of a three-stage rocket. In a classified report, the agency described the event as a "stupendous scientific achievement" and concluded that the USSR had likely perfected an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of accurately targeting any location.[76] In reality, the launch weight of the Soviet rocket was 267 metric tons with an initial thrust of 410 tons with one and a half stages. The CIA's misjudgement was caused by extrapolating the parameters of the US Atlas rocket developed at the same time (launch weight 82 tons, initial thrust 135 tones, maximum payload of 70 kg for low Earth orbit).[77] In part, the favourable data of the Soviet launcher was based on concepts proposed by the German rocket scientists headed by Helmut Gröttrup on Gorodomlya Island, such as, among other things, the rigorous weight saving, the control of the residual fuel quantities and a reduced thrust to weight relation of 1.4 instead of usual factor 2.[78] The CIA had heard about such details already in January 1954 when it interrogated Göttrup after his return from the USSR but did not take him seriously.[79]

US reactions

The Soviet success raised a great deal of concern in the United States. For example, economist Bernard Baruch wrote in an open letter titled "The Lessons of Defeat" to the New York Herald Tribune: "While we devote our industrial and technological power to producing new model automobiles and more gadgets, the Soviet Union is conquering space. ... It is Russia, not the United States, who has had the imagination to hitch its wagon to the stars and the skill to reach for the moon and all but grasp it. America is worried. It should be."[80]

Eisenhower ordered project Vanguard to move up its timetable and launch its satellite much sooner than originally planned.

Explorer

On January 31, 1958, nearly four months after the launch of Sputnik 1, von Braun and the United States successfully launched its first satellite on a four-stage

Creation of NASA

On April 2, 1958, President Eisenhower reacted to the Soviet space lead in launching the first satellite by recommending to the US Congress that a civilian agency be established to direct nonmilitary space activities. Congress, led by

On October 21, 1959, Eisenhower approved the transfer of the Army's remaining space-related activities to NASA. On July 1, 1960, the Redstone Arsenal became NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, with von Braun as its first director. Development of the Saturn rocket family, which when mature gave the US parity with the Soviets in terms of lifting capability, was thus transferred to NASA.[93]

First mammals in space

The US and the USSR sent animals into space to determine the safety of the environment before sending the first humans. The USSR used

The USSR sent the dog Laika into orbit on Sputnik 2, the second satellite launched, on November 3, 1957, for an intended ten-day flight.[74] They did not yet have the technology to return Laika safely to Earth, and the government reported Laika died when the oxygen ran out,[95] but in October 2002 her true cause of death was reported as stress and overheating on the fourth orbit[96] due to failure of the air conditioning system.[97] At a Moscow press conference in 1998 Oleg Gazenko, a senior Soviet scientist involved in the project, stated "The more time passes, the more I'm sorry about it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog...".[98]

Early lunar probes

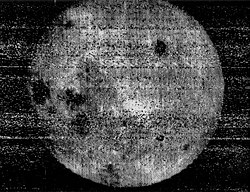

In 1958, Korolev upgraded the R-7 to be able to launch a 400-kilogram (880 lb) payload to the Moon. The Luna program began with three failed secret 1958 attempts to launch Luna E-1-class impactor probes.[99] The fourth attempt, Luna 1, launched successfully on January 2, 1959, but missed the Moon. The fifth attempt on June 18 also failed at launch. The 390-kilogram (860 lb) Luna 2 successfully impacted the Moon on September 14, 1959. The 278.5-kilogram (614 lb) Luna 3 successfully flew by the Moon and sent back pictures of its far side on October 7, 1959.[100]

The US first embarked on the Pioneer program in 1958 by launching the first probe, albeit ending in failure. A subsequent probe named Pioneer 1 was launched with the intention of orbiting the Moon only to result in a partial mission success when it reached an apogee of 113,800 km before falling back to Earth. The missions of Pioneer 2 and Pioneer 3 failed whereas Pioneer 4 had one partially successful lunar flyby in March 1959.[101][102]

Human spaceflight, space treaties, interplanetary probes (1961–1968)

The period from 1961 to 1968 began with the first men sent to space, the first robotic explorations of other planets; with missions to Venus and Mars conducted by both the Soviet Union and the United States, robotic landings on the Moon, and the gestation of US ambition to land a man on the moon. The 60s saw significant advancements in crewed spaceflight by both cold war adversaries, as well as the first nuclear detonation in space, research into anti-satellite technology, and the signing of historic international outer space treaties.

First humans in space

Vostok

The Soviets designed their first human

On April 12, 1961, the USSR surprised the world by launching

Gagarin became a national hero of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and a worldwide celebrity. Moscow and other cities in the USSR held mass demonstrations, the scale of which was second only to the

The USSR demonstrated 24-hour launch pad turnaround and launched two piloted spacecraft,

Mercury

The US Air Force had been developing a program to launch the first man in space, named Man in Space Soonest. This program studied several different types of one-man space vehicles, settling on a ballistic re-entry capsule launched on a derivative Atlas missile, and selecting a group of nine candidate pilots. After NASA's creation, the program was transferred over to the civilian agency's Space Task Group and renamed Project Mercury on November 26, 1958. The Mercury spacecraft was designed by the STG's chief engineer Maxime Faget. NASA selected a new group of astronaut (from the Greek for "star sailor") candidates from Navy, Air Force and Marine test pilots, and narrowed this down to a group of seven for the program. Capsule design and astronaut training began immediately, working toward preliminary suborbital flights on the Redstone missile, followed by orbital flights on the Atlas. Each flight series would first start unpiloted, then carry a non-human primate, then finally humans.[118]

The Mercury spacecraft's principal designer was

On May 5, 1961,

American

The United States launched three more Mercury flights after Glenn's:

Kennedy aims for a crewed Moon landing

These are extraordinary times. And we face an extraordinary challenge. Our strength, as well as our convictions, have imposed upon this nation the role of leader in freedom's cause.

... if we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take. ... Now it is time to take longer strides – time for a great new American enterprise – time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

... Recognizing the head start obtained by the Soviets with their large rocket engines, which gives them many months of lead-time, and recognizing the likelihood that they will exploit this lead for some time to come in still more impressive successes, we nevertheless are required to make new efforts on our own.

... I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space, and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

... Let it be clear that I am asking the Congress and the country to accept a firm commitment to a new course of action—a course which will last for many years and carry very heavy costs: 531 million dollars in fiscal '62—an estimated seven to nine billion dollars additional over the next five years. If we are to go only half way, or reduce our sights in the face of difficulty, in my judgment it would be better not to go at all.

Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs, May 25, 1961[10]

Before Gagarin's flight, US President John F. Kennedy's support for America's piloted space program was lukewarm. Jerome Wiesner of MIT, who served as a science advisor to presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy, and himself an opponent of sending humans into space, remarked, "If Kennedy could have opted out of a big space program without hurting the country in his judgment, he would have."[130] As late as March 1961, when NASA administrator James E. Webb submitted a budget request to fund a Moon landing before 1970, Kennedy rejected it because it was simply too expensive.[131] Some were surprised by Kennedy's eventual support of NASA and the space program because of how often he had attacked the Eisenhower administration's inefficiency during the election.[132]

Gagarin's flight changed this; now Kennedy sensed the humiliation and fear on the part of the American public over the Soviet lead. Additionally, the

Kennedy ultimately decided to pursue what became the Apollo program, and on May 25 took the opportunity to ask for Congressional support in a Cold War speech titled "Special Message on Urgent National Needs". Full text ![]() He justified the program in terms of its importance to national security, and its focus of the nation's energies on other scientific and social fields.

He justified the program in terms of its importance to national security, and its focus of the nation's energies on other scientific and social fields.

Khrushchev responded to Kennedy's challenge with silence, refusing to publicly confirm or deny the Soviets were pursuing a "Moon race".

Proposed joint US-USSR program

After a first US-USSR

Some cooperation in robotic space exploration nevertheless did take place,

As President, Johnson steadfastly pursued the Gemini and Apollo programs, promoting them as Kennedy's legacy to the American public. One week after Kennedy's death, he issued Executive Order 11129 renaming the Cape Canaveral and Apollo launch facilities after Kennedy.

Lunar probes and robotic landers

The

In 1963, the Soviet Union's "2nd Generation" Luna programme was less successful than the earlier Luna probes;

The Zond programme was orchestrated alongside the Luna programme with Zond 1 and Zond 2 launching in 1964, intended as flyby missions, however both failed.[153][154] Zond 3 however was successful, and transmitted high quality photography from the far side of the moon.[155][156]

Partly to aid the Apollo missions, the Surveyor program was conducted by NASA, with five successful soft landings out of seven attempts from 1966 to 1968. The Lunar Orbiter program had five successes out of five attempts in 1966–1967.[157][158]

In late 1966, Luna 13 became the third spacecraft to make a soft-landing on the Moon, with the American Surveyor 1 having now taken second. Luna 13 made use of inflatable air-bags to soften it's landing.[159][160][161] Surveyor 1 was a 995 kg lander, notably larger than the 112 kg Luna 13 E-6M lander.[159][162] Surveyor 1 was equipped with a Doppler velocity sensing system that fed information into the spacecraft computer to implement a controllable descent to the surface. Each of the three landing pads also carried aircraft-type shock absorbers and strain gauges to provide data on landing characteristics, important for future Apollo missions.[163][164]

Surveyor 3, which successfully touched down on the Moon April 20, 1967, carried a 'surface sampler' which facilitated tests of the Lunar soil. Based on these experiments, scientists concluded that lunar soil had a consistency similar to wet sand, with a bearing strength of about 10 pounds per square inch (0.7 kilograms per square centimeter, or 98 kilopascals), which was concluded to be solid enough to support an Apollo Lunar Module.[165] The Surveyor 3 lander would be later visited by Apollo 12 astronauts.[166]

On Nov. 17, 1967, before mission termination, Surveyor 6 fired its thrusters for 2.5 seconds, becoming the first spacecraft launched from the lunar surface. It rose about 10 feet (3 meters) before landing 8 feet (2.5 meters) west of its original spot. Cameras then examined the original landing site to assess the soil's properties.[167][168]

First interplanetary probes

From the early 60s both cold war adversaries almost simultaneously initiated their own programmes which sought to reach other planets in the solar system for the first time; namely Venus and Mars.

Venus

Venus was of great interest in the field of planetary science due to its thick and opaque atmosphere, the atmospheres of other planets being a novel area of research at the time.

In 1961 the Venera Programme was initiated by the Soviet Union, with the launch of Venera 1. The programme would go on to mark many firsts in the exploration of another planet. Despite the later successes however, Venera 1 and Venera 2, intended to flyby Venus, resulted in failure due to losses of contact.[169][170]

NASA would then initiate the Mariner program with the launch of Mariner 1 and Mariner 2. Mariner 1 failed shortly after launch,[171] however Mariner 2 would become the first man-made object to flyby another Planet in December 1962 when the probe passed by Venus.[172][173]

Later in 1965/66, Venera 3, marked the first time a man-made object made contact with another planet after it impacted Venus on March 1, 1966, despite operational difficulties resulting in loss of contact with the craft.[174]

In 1967, Mariner 5 flew by Venus and conducted atmospheric analysis.[175]

Mars

In 1964, NASA's Mariner 4 became the first successful Mars flyby, transmitting 21 pictures of the planets surface. This was followed by Mariner 6 and 7 in 1969.

First crewed spacecraft

Focused by the commitment to a Moon landing, in January 1962 the US announced Project Gemini, a two-person spacecraft that would support the later three-person Apollo by developing the key spaceflight technologies of

Meanwhile, Korolev had planned further long-term missions for the Vostok spacecraft, and had four Vostoks in various stages of fabrication in late 1963 at his

Voskhod

Korolev's conversion of his surplus Vostok capsules to the

On March 18, 1965, about a week before the first piloted Project Gemini space flight, the USSR launched the two-cosmonaut Voskhod 2 mission with Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov.[183] Voskhod 2's design modifications included the addition of an inflatable airlock to allow for extravehicular activity (EVA), also known as a spacewalk, while keeping the cabin pressurized so that the capsule's electronics would not overheat.[184] Leonov performed the first-ever EVA as part of the mission.[183] A fatality was narrowly avoided when Leonov's spacesuit expanded in the vacuum of space, preventing him from re-entering the airlock.[185] To overcome this, he had to partially depressurize his spacesuit to a potentially dangerous level.[185] He succeeded in safely re-entering the spacecraft, but he and Belyayev faced further challenges when the spacecraft's atmospheric controls flooded the cabin with 45% pure oxygen, which had to be lowered to acceptable levels before re-entry.[186] The reentry involved two more challenges: an improperly timed retrorocket firing caused the Voskhod 2 to land 386 kilometers (240 mi) off its designated target area, the city of Perm; and the instrument compartment's failure to detach from the descent apparatus caused the spacecraft to become unstable during reentry.[186]

By October 16, 1964, Leonid Brezhnev and a small cadre of high-ranking Communist Party officials deposed Khrushchev as Soviet government leader a day after Voskhod 1 landed, in what was called the "Wednesday conspiracy".[187] The new political leaders, along with Korolev, ended the technologically troublesome Voskhod program, canceling Voskhod 3 and 4, which were in the planning stages, and started concentrating on reaching the Moon.[188] Voskhod 2 ended up being Korolev's final achievement before his death on January 14, 1966, as it became the last of the space firsts that the USSR achieved during the early 1960s. According to historian Asif Siddiqi, Korolev's accomplishments marked "the absolute zenith of the Soviet space program, one never, ever attained since."[7] There was a two-year pause in Soviet piloted space flights while Voskhod's replacement, the Soyuz spacecraft, was designed and developed.[189]

Gemini

Though delayed a year to reach its first flight, Gemini was able to take advantage of the USSR's two-year hiatus after Voskhod, which enabled the US to catch up and surpass the previous Soviet superiority in piloted spaceflight. Gemini had ten crewed missions between March 1965 and November 1966: Gemini 3, Gemini 4, Gemini 5, Gemini 6A, Gemini 7, Gemini 8, Gemini 9A, Gemini 10, Gemini 11, and Gemini 12; and accomplished the following:

- Every mission demonstrated the ability to adjust the crafts' inclination and apsis without issue.

- Gemini 5 demonstrated eight-day endurance, long enough for a round trip to the Moon. Gemini 7 demonstrated a fourteen-day endurance flight.

- Gemini 6A demonstrated rendezvous and Agena Target Vehicle(ATV).

- Rendezvous and docking with the ATV was achieved on Gemini 8, 10, 11, and 12. Gemini 11 achieved the first direct-ascent rendezvous with its Agena target on the first orbit.

- Edwin "Buzz" Aldrinspent over five hours working comfortably during three (EVA) sessions, finally proving that humans could perform productive tasks outside their spacecraft.

- Gemini 10, 11, and 12 used the ATV's engine to make large changes in its orbit while docked. Gemini 11 used the Agena's rocket to achieve a crewed Earth orbit record apogeeof 742 nautical miles (1,374 km).

Gemini 8 experienced the first in-space mission abort on March 17, 1966, just after achieving the world's first docking, when a stuck or shorted thruster sent the craft into an uncontrolled spin. Command pilot Neil Armstrong was able to shut off the stuck thruster and stop the spin by using the re-entry control system.[191] He and his crewmate David Scott landed and were recovered safely.[192]

Most of the novice pilots on the early missions would command the later missions. In this way, Project Gemini built up spaceflight experience for the pool of astronauts for the Apollo lunar missions. With the completion of Gemini, the US had demonstrated many of the key technologies necessary to make Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the Moon, namely crewed spacecraft docking, with the exception of developing a large enough launch vehicle.[193]

Soviet crewed Moon programs

Korolev's design bureau produced two prospectuses for circumlunar spaceflight (March 1962 and May 1963), the main spacecraft for which were early versions of his Soyuz design. At the same time, another bureau,

Officially, the Soviet lunar program was established on August 3, 1964, with the adoption of Soviet Communist Party Central Committee Command 655-268 (On Work on the Exploration of the Moon and Mastery of Space).[140] The circumlunar flights were planned to occur in 1967, and the landings to start in 1968, intending to land a person on the Moon before the Apollo flights.[195] Both of the bureaus submitted their projects for a crewed lunar landing.[140]

Korolev's lunar landing program was designated N1/L3, for its N1 super rocket and a more advanced Soyuz 7K-L3 spacecraft, also known as the lunar orbital module ("Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl", LOK), with a crew of two. A separate lunar lander ("Lunniy Korabl", LK), would carry a single cosmonaut to the lunar surface.[195]

The N1/L3 launch vehicle had three stages to Earth orbit, a fourth stage for Earth departure, and a fifth stage for lunar landing assist. The combined space vehicle was roughly the same height and takeoff mass as the three-stage US

Chelomey's program assumed using a direct ascent lander based on the LK-1, LK-700, which would be launched using his proposed UR-700 rocket. Following Khrushchev's ouster from power, Chelomey lost his support in the Soviet government, and his proposal didn't receive any funding. Additionally, in August 1965, due to Korolev's opposition, work on the LK-1 was suspended, and later stopped completely. As a replacement, the circumlunar mission would use a stripped-down Soyuz 7K-L1 "Zond", while still retaining the Proton UR-500 booster. To fit two crewmembers, the Zond had to omit the Soyuz orbital module, sacrificing equipment for habitable cabin volume.[194][199]

Outer space treaties

The US and USSR began discussions on the peaceful uses of space as early as 1958, presenting issues for debate to the United Nations,[200][201][202] which created a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in 1959.[203]

On May 10, 1962, Vice President Johnson addressed the Second National Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Space revealing that the United States and the USSR both supported a resolution passed by the Political Committee of the UN General Assembly in December 1962, which not only urged member nations to "extend the rules of international law to outer space," but to also cooperate in its exploration. Following the passing of this resolution, Kennedy commenced his communications proposing a cooperative American and Soviet space program.[204]

In 1963, the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed by more than 100 signatories, including both the United States and the Soviet Union. This treaty followed the US test of a nuclear bomb detonated in outer space the year earlier called Starfish Prime.

The UN ultimately created a Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, which was signed by the United States, the USSR, and the United Kingdom on January 27, 1967, and came into force the following October 10.[205]

This treaty:

- bars party States from placing weapons of mass destructionin Earth orbit, on the Moon, or any other celestial body;

- exclusively limits the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes, and expressly prohibits their use for testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications;

- declares that the exploration of outer space shall be done to benefit all countries and shall be free for exploration and use by all the States;

- explicitly forbids any government from claiming a celestial resource such as the Moon or a planet, claiming that they are the common heritage of mankind, "not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means". However, the State that launches a space object retains jurisdiction and control over that object;

- holds any State liable for damages caused by their space object;

- declares that "the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty", and "States Parties shall bear international responsibility for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities"; and

- "A State Party to the Treaty which has reason to believe that an activity or experiment planned by another State Party in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause potentially harmful interference with activities in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, may request consultation concerning the activity or experiment."

The treaty remains in force, signed by 107 member states. – As of July 2017[update]

Anti-Satellite research

Istrebitel-sputnikov

In November 1968, dismay gripped the United States Central Intelligence Agency when a successful satellite destruction simulation was successfully orchestrated by the Soviet Union.[206] As a part of the Istrebitel Sputnikov anti-satellite weapons research programme, the Kosmos 248 Soviet satellite was successfully destroyed by Kosmos 252 which was able to intercept within the 5 km 'kill radius' and destroyed Kosmos 248 by detonating its onboard warhead. This wasn't the beginning of the programme, years earlier intercept attempts had begun with maneuvering test of the Polyot satellites in 1964.[207][208][209][210]

SAINT

Possibly as a response to the Soviet programme, the United States began Project SAINT, which was intended to provide anti-satellite capability to be used in the case of war with the Soviet Union.[211][206][212] However, less is known about the mission profiles of this project compared to the Soviet programme, and the project was cancelled early on due to budget constraints.[212]

Disaster strikes both sides

In 1967, both nations' space programs faced serious challenges that brought them to temporary halts.

Apollo 1

On January 27, 1967, the same day the US and USSR signed the Outer Space Treaty, the crew of the first crewed Apollo mission, Command Pilot

Soyuz 1

On April 24, 1967, the single pilot of Soyuz 1,

Both programs recover

The United States recovered from the Apollo 1 fire, fixing the fatal flaws in an improved version of the

The Soviet Union also fixed the parachute and control problems with Soyuz, and the next piloted mission Soyuz 3 was launched on October 26, 1968.[227] The goal was to complete Komarov's rendezvous and docking mission with the un-piloted Soyuz 2.[227] Ground controllers brought the two craft to within 200 meters (660 ft) of each other, then cosmonaut Georgy Beregovoy took control.[227] He got within 40 meters (130 ft) of his target, but was unable to dock before expending 90 percent of his maneuvering fuel, due to a piloting error that put his spacecraft into the wrong orientation and forced Soyuz 2 to automatically turn away from his approaching craft.[227] The first docking of Soviet spacecraft was finally realized in January 1969 by the Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 missions. It was the first-ever docking of two crewed spacecraft, and the first transfer of crew from one space vehicle to another.[228]

The Soviet

During the summer of 1968, the Apollo program hit another snag: the first pilot-rated Lunar Module (LM) was not ready for orbital tests in time for a December 1968 launch. NASA planners overcame this challenge by changing the mission flight order, delaying the first LM flight until March 1969, and sending

On December 21, 1968, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders became the first humans to ride the Saturn V rocket into space, on Apollo 8. They also became the first to leave low-Earth orbit and go to another celestial body, entering lunar orbit on December 24.[238] They made ten orbits in twenty hours, and transmitted one of the most watched TV broadcasts in history, with their Christmas Eve program from lunar orbit, which concluded with a reading from the biblical Book of Genesis.[238] Two and a half hours after the broadcast, they fired their engine to perform the first trans-Earth injection to leave lunar orbit and return to the Earth.[238] Apollo 8 safely landed in the Pacific Ocean on December 27, in NASA's first dawn splashdown and recovery.[238]

The American Lunar Module was finally ready for a successful piloted test flight in low Earth orbit on Apollo 9 in March 1969. The next mission, Apollo 10, conducted a "dress rehearsal" for the first landing in May 1969, flying the LM in lunar orbit as close as 47,400 feet (14.4 km) above the surface, the point where the powered descent to the surface would begin.[239] With the LM proven to work well, the next step was to attempt the landing.

Unknown to the Americans, the Soviet Moon program was in deep trouble.[237] After two successive launch failures of the N1 rocket in 1969, Soviet plans for a piloted landing suffered delay.[240] The launch pad explosion of the N-1 on July 3, 1969, was a significant setback.[241] The rocket hit the pad after an engine shutdown, destroying itself and the launch facility.[241] Without the N-1 rocket, the USSR could not send a large enough payload to the Moon to land a human and return him safely.[242]

Men on the Moon, space stations, space shuttles (1969–1991)

The latter period of the space race began with the United States landing the first men on the moon, and was followed by the Soviets operating the first space stations and putting the first robotic landers on Venus and Mars, the US space shuttles marking the first significant reusable space vehicles, and a cooling down of tensions with the first docking between a Soviet and American vessel.

First humans on the Moon

Apollo 11 was prepared with the goal of a July landing in the

The trip to the Moon took just over three days.

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The first step was witnessed on live television by at least one-fifth of the population of Earth, or about 723 million people.[249] His first words when he stepped off the LM's landing footpad were, "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."[248] Aldrin joined him on the surface almost 20 minutes later.[250] Altogether, they spent just under two and one-quarter hours outside their craft.[251] The next day, they performed the first crewed launch from another celestial body, and rendezvoused back with Collins in Columbia.[252] But before they return ascended the Space Race came to a particular culmination.[253] Few days before Apollo 11 left Earth the Soviet Union launched the Luna 15 probe, entering lunar orbit just before Apollo 11 and eventually sharing it with Apollo 11. Aware of Luna 15, Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman was asked to use his goodwill contacts in the Soviet Union to prevent any collision. Subsequently, in one of the first instances of Soviet–American space communication the Soviet Union released Luna 15's flight plan to ensure it would not collide with Apollo 11, although its exact mission was not publicized.[254] But as Apollo 11 was wrapping up surface activities, the Soviet mission command hastened Luna 15 and attempted its robotic sample-return mission before Apollo 11 would return. As Luna 15 descended just two hours before Apollo 11's launch and impacted at 15:50 UTC some hundred kilometers away from Apollo 11, British astronomers monitoring Luna 15 recorded the situation, with one commenting:“I say, this has really been drama of the highest order”.[255]

Apollo 11 left lunar orbit and returned to Earth, landing safely in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969.[256] When the spacecraft splashed down, 2,982 days had passed since Kennedy's commitment to landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade; the mission was completed with 161 days to spare.[257] With the safe completion of the Apollo 11 mission, the Americans won the race to the Moon.[258]

Armstrong and his crew became worldwide celebrities, feted with ticker-tape parades on August 13 in New York City and Chicago, attended by an estimated six million.

The public's reaction in the Soviet Union was mixed. The Soviet government limited the release of information about the lunar landing, which affected the reaction. A portion of the populace did not give it any attention, and another portion was angered by it.[264]

The first landing was followed by another, precision landing on Apollo 12 in November 1969, within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 spacecraft which landed on April 20, 1967.

In total the Apollo programme involved six crewed Moon landings from 1969 to 1972, and a total of twelve astronauts walked on the surface of the Moon. These were Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17.

Post-Apollo NASA: Shifting goals and budget cuts

NASA had ambitious follow-on human spaceflight plans as it reached its lunar goal but soon discovered it had expended most of its political capital to do so.[265] A victim of its own success, Apollo had achieved its first landing goal with enough spacecraft and Saturn V launchers left for a total of ten lunar landings through Apollo 20, conducting extended-duration missions and transporting the landing crews in Lunar Roving Vehicles on the last five. NASA also planned an Apollo Applications Program (AAP) to develop a longer-duration Earth orbital workshop (later named Skylab) from a spent S-IVB upper stage, to be constructed in orbit using several launches of the smaller Saturn IB launch vehicle.

In February 1969, President

AAP planners decided the Earth orbital workshop could be accomplished more efficiently by prefabricating it on the ground and launching it with a single Saturn V, which immediately eliminated Apollo 20. Budget cuts soon led NASA to cut Apollo 18 and 19 as well. Apollo 13 had to abort its lunar landing in April 1970 due to an in-flight spacecraft failure but returned its crew safely to Earth. The Apollo program made its final lunar landing in December 1972; the two unused Saturn Vs were used as outdoor visitor displays and allowed to deteriorate due to the effects of weathering.

The USSR continued trying to develop its N1 rocket, after two more launch failures in 1971 and 1972, finally canceling it in May 1974, without achieving a single successful uncrewed test flight.[269]

Soviet Lunar sample return and robotic rovers

In late 1970 Luna 16 was launched by the Soviet Union, and became the first uncrewed probe to return a sample from the Moon. This was followed by Luna 20 and Luna 24 in subsequent years.[270][271]

The Soviet Union was also able to successfully land the first robotic rover on the moon in 1970, followed by another in 1973, with the Lunokhod missions.[272]

These missions demonstrated continued Soviet willingness to compete with the US in the space race despite having lost the manned moon landing aspect of the space race.

Salyut and Skylab

Having lost the race to the Moon, the USSR seemed to decide to concentrate on orbital space stations instead of pursuing a crewed lunar mission. During 1969 and 1970, they launched six more Soyuz flights after Soyuz 3 and then launched a series of six successful space stations (plus two failures to achieve orbit and one station rendered uninhabitable due to damage from explosion of the launcher's upper stage) on their Proton-K heavy-lift launcher in their Salyut program designed by Kerim Kerimov. Each one weighed between 18,500 and 19,824 kilograms (40,786 and 43,704 lb), was 20 meters (66 ft) long by 4 meters (13 ft) in diameter, and had a habitable volume of 99 cubic meters (3,500 cu ft). All of the Salyuts were presented to the public as non-military scientific laboratories, but three of them were covers for military Almaz reconnaissance stations: Salyut 2 (failed),[273] Salyut 3,[274] and Salyut 5.[275][276]

The United States launched a single orbital workstation, Skylab, on May 14, 1973. It was launched using a leftover Saturn-5 rocket from the Apollo programme.[280] Skylab weighed 169,950 pounds (77,090 kg), was 58 feet (18 m) long by 21.7 feet (6.6 m) in diameter, and had a habitable volume of over 10,000 cubic feet (280 m3). Skylab was damaged during the ascent to orbit, losing one of its solar panels and a meteoroid thermal shield. Subsequent crewed missions repaired the station, and conducted valuable research. The third and final mission's crew, Skylab 4, set a human endurance record (at the time) with 84 days in orbit when the mission ended on February 8, 1974. Skylab stayed in orbit another five years before reentering the Earth's atmosphere over the Indian Ocean and Western Australia on July 11, 1979.[281]

Salyut 4 broke Skylab's occupation record at 92 days. Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 were second-generation stations designed for long duration, and were occupied for 683 and 816 days. Salyut 7 improved upon earlier designs by allowing long-duration crewed missions and more complex experiments. These stations, with their expanded crew capacity and amenities for long term stay, carrying electric stoves, a refrigerator, and constant hot water.[282]

Venus and Mars robotic landings

Venus landings

In 1970, the Soviet Union's Venera 7 marked the first time a spacecraft was able to return data after landing on another planet.[283] Venera 7 held a resistant thermometer and an aneroid barometer to measure the temperature and atmospheric pressure on the surface, the transmitted data showed 475 C at the surface, and a pressure of 92 bar.[284][285][283][286]

In 1975, Venera 9 established an orbit around Venus and successfully returned the first photography of the surface of Venus.[287][288] Venera 10 landed on Venus and followed with further photography shortly after.[289]

NASA initiated the Pioneer Venus project in 1978, successfully deploying four small probes into the Venusian atmosphere on December 9, 1978. The probes confirmed that Venus has little if any magnetic field, and cameras detected lightning in the atmosphere. The last transmissions were received on October 8, 1992, as its decaying orbit no longer permitted communications. The spacecraft burned up the atmosphere soon after, ending a successful 14-year mission that was planned to last only eight months.[290]

In 1981, Venera 13 performed a successful soft-landing on Venus and marked the first probe to drill into the surface of another planet and take a sample.[291][292] Venera 13 also took an audio sample of the Venusian environment, marking another first.[293] Venera 13 returned the first color images of the surface of Venus, revealing an orange-brown flat bedrock surface covered with loose regolith and small flat thin angular rocks.[291] Venera 14, an identical spacecraft to Venera 13, was launched 5 days apart with a similar mission profile.[294]

In total ten Venera probes achieved a soft landing on the surface of Venus.

In 1984, the Soviet Vega programme began and ended with the launch of two crafts launched six days apart, Vega 1 and Vega 2. Both crafts deployed a balloon in addition to a lander, marking a first in spaceflight.[295][296][297]

The US never caught up or matched the Soviet efforts to explore the surface of Venus, but did claim the title of the first successful probe to have flown by the planet and had notable success with the Pioneer atmospheric probes.

Mars landings

In 1971, the Soviet's Mars 2 successfully established Mars orbit and attempted a soft landing but crashed, becoming the first man-made object to impact Mars. This was shortly followed by Mars 3, a 358 kg lander, which successfully landed but the lander only transmitted data for 14.5 seconds before losing contact.[300]

In 1976, NASA followed suit, and put two successful landers on Mars. These were Viking 1 and Viking 2. These landers were significantly larger than the Soviet Mars landers (Viking 1 was 3,527 kilograms). They were able to take the first photographs from the surface of Mars.[301][302]

Viking 1 operated on the surface of Mars for around six years (On Nov 11, 1982 the Lander stopped operating after getting a faulty command) and Viking 2 for over three years (mission ended in early 1980). Both landers were equipped with a robotic sampler arm which successfully scooped up soil samples and tested them with instruments such as a Gas chromatography–mass spectrometer. The landers measured temperatures ranging from negative 86 degrees Celsius before dawn to negative 33 degrees Celsius in the afternoon. Both landers had issues obtaining accurate results from their seismometers.[302][303][304][305]

Photographs from the landers and orbiters surpassed expectations in quality and quantity. The total exceeded 4,500 from the landers and 52,000 from the orbiters.

The Viking landers recorded atmospheric pressures ranging from below 7 millibars (0.0068 bars) to over 10 millibars (0.0108 bars) over the Martian year, leading to the conclusion that atmospheric pressure varies by 30 percent during the Martian year because carbon dioxide condenses and sublimes at the polar caps. Martian winds generally blow more slowly than expected, scientists had expected them to reach speeds of several hundred miles an hour from observing global dust storms, but neither lander recorded gusts over 120 kilometers (74 miles) an hour, and average velocities were considerably lower. Nevertheless, the orbiters observed more than a dozen small dust storms. The Viking landers detected nitrogen in the atmosphere for the first time, and that it was a significant component of the Martian atmosphere. There was speculation from the atmospheric analysis that the atmosphere of Mars used to be much denser.[306][307]

The Soviets did not match the Martian lander achievements of NASA, but did claim the title of the first lander.[308]

Apollo–Soyuz Test Project

In May 1972, President Richard M. Nixon and Soviet

The joint mission began when

Space Shuttles

NASA achieved the first approach and landing test of its

The Soviets interpreted the Shuttle as a military surveillance vehicle, and decided they had to develop their own shuttle, which they named

First women in space

The first woman in space was from the Soviet Union, Valentina Tereshkova. NASA did not welcome female astronauts into its corps until 1978, when six female mission specialists were recruited. This first class included scientist Sally Ride, who became America's first woman in space on STS-7 in June 1983. NASA included women mission specialists in the next four astronaut candidate classes, and admitted female pilots starting in 1990. Eileen Collins from this class became the first pilot to fly on Space Shuttle flight STS-63 in February 1995, and the first female commander of a spaceflight on STS-93 in July 1999.

The USSR admitted its first female test pilot as a cosmonaut, Svetlana Savitskaya, in 1980. She became the first female to fly since Tereshkova, on Salyut 7 in December 1981.

First modular space station

The USSR turned its space program to the development of the low Earth orbit modular space station

Analysis and reception

"Winner" of the Space Race

The question of who won the Space Race has sparked considerable debate among historians and analysts. The United States is widely seen as the victor due to the Apollo crewed landing and moonwalk missions, which achieved President John F. Kennedy's ambitious goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth by the end of the 1960s. This achievement, completed in July 1969, marked the pinnacle of U.S. space exploration efforts of the time and was regarded by most observers as the culmination of the Space Race. Political scientist Richard J. Samuels describes Apollo 11 as a "decisive American victory."[15]

The Moon race is often analyzed as a microcosm of the Space Race's broader dynamics. Historians such as Jennifer Frost argue that if the Space Race is measured in terms of overall spaceflight capability, the Soviet Union "won it hands down."[316] Asif A. Siddiqi, a noted space historian, provides a more nuanced view, emphasizing the Soviet Union's dominance in smaller aspects of the race to the moon, yet critical, benchmarks such as the first lunar impact, first photos of the Moon's far side, first soft lunar landing, and first lunar orbit.[317] These accomplishments laid the groundwork for lunar exploration, though they are often overshadowed by the Apollo 11 mission.

Before that landing [Apollo 11], there was an enormous amount of investment in the robotic exploration of the Moon, both by the Soviets and the US, in terms of all sorts of smaller benchmarks like the first lunar impact, the first pictures of the far side of the Moon, the first soft lunar landing, and the first lunar orbit. We forget, but in those little races, the Soviet Union dominated almost every benchmark, but it is forgotten as the United States won the big one.

Historians' analysis

The Space Race was deeply intertwined with Cold War rivalries and reflected broader ideological contests between the United States and the Soviet Union. Historian Walter McDouglass highlights how space exploration served as a demonstration of each superpower's political and technological systems, with the U.S. emphasizing transparency and democratic values, and the USSR showcasing the capabilities of its centralized, state-driven model.[318][319] Asif A. Siddiqi stresses the importance of viewing the Space Race as more than a single-event competition. He notes that while the U.S. achieved the symbolic "big one" with the Apollo missions, the Soviet Union's early and sustained achievements in robotic lunar and interplanetary exploration reveal the broader, multi-faceted nature of the rivalry.[317]

Legacy

After the end of the Cold War in 1991, the assets of the USSR's space program passed mainly to

In 2023 the Russian Federation resumed the Luna missions as a part of the Luna-Glob programme with the launch of Luna 25 (47 years after the Soviet Luna 24),[322] amidst American reignition of interest in the Moon with the Artemis program beginning with the launch of Artemis I in 2022.[323]

See also

- Billionaire space race

- Cold War

- Arms race

- Cold War playground equipment

- History of spaceflight

- List of space exploration milestones, 1957–1969

- Moon landing

- Moon Shot

- Space advocacy

- Space exploration

- Space policy

- Space propaganda

- Spaceflight records

- SEDS

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- Timeline of space exploration

- Woods Hole Conference

- Mars race

References

- ^ "The Space Race". History.com. February 21, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Space Race". airandspace.si.edu. March 6, 2023. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ updated, Adam MannContributions from Callum McKelvie last (July 8, 2022). "What was the space race?". Space.com. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Space Program | JFK Library". www.jfklibrary.org. November 21, 2024. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "How Did NASA'S "Vomit Comet" Get Its Name? A Brief History". gozerog.com. June 30, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

A Soviet youth magazine in 1951 is often credited with sparking public interest in space travel. Quickly picked up by US magazines, the idea of extending the Cold War playing board to outer space soon energized the imaginations of politicians, military leaders, and the private sector.

- ^ a b c d e Schefter 1999, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2003a, p. 460.

- ^ "Sputnik and the Origins of the Space Age". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "The Space Race | Miller Center". millercenter.org. September 11, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Kennedy, John F. (May 25, 1961). Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs (Motion picture (excerpt)). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Accession Number: TNC:200; Digital Identifier: TNC-200-2. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Lunar Module / EASEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Summary". Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.

- ^ Williams, David R. (December 11, 2003). "Apollo Landing Site Coordinates". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. NASA. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7619-2927-7.

Most observers felt that the U.S. moon landing ended the space race with a decisive American victory. […] The formal end of the space race occurred with the 1975 joint Apollo–Soyuz mission, in which U.S. and Soviet spacecraft docked, or joined, in orbit while their crews visited one another's craft and performed joint scientific experiments.

- ^ a b U.S.-Soviet Cooperation in Space (PDF) (Report). US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. July 1985. pp. 80–81. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (March 23, 2001). "Russia bids farewell to Mir". NBC News. New York. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (April 30, 2015). "ISS Facts and Figures". International Space Station. NASA. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-02-922895-1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 89.

- ^ Schmitz 1999, pp. 149–54.

- ^ a b "Timeline: U.S.-Russia Nuclear Arms Control". www.cfr.org. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ "R-7 - SS-6 SAPWOOD Russian / Soviet Nuclear Forces". nuke.fas.org. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons and the Escalation of the Cold War, 1945-1962 | Department of History". history.stanford.edu. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ "Cold War Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles I". weaponsandwarfare. January 10, 2020.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 164-5 Vol 1.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 165 Vol 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 4-5.

- ^ "GIRD (Gruppa Isutcheniya Reaktivnovo Dvisheniya)". WEEBAU. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly. "Gas Dynamics Laboratory". Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 167 vol 1.

- ^ "Greatest World War II Weapons: The Fearsome Katyusha Rocket Launcher". Defencyclopidea. February 20, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 9.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 167-8 Vol 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 24-39.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 41 Vol 2.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 49.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-0299-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-0306-1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 48-49 Vol 2.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 242-285 Vol 2.

- OCLC 1316077842.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 128-132.

- ^ a b "The Military Rockets that Launched the Space Age". National Air and Space Museum. August 9, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ^ "R-7 History". www.worldspaceflight.com. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 160-161.

- ^ "Russian Rockets and Space Launchers". Historic Spacecraft. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly. "The R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile". Russian Space Web. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Schefter 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Burrows 1998, p. 123.

- ^ a b Burrows 1998, pp. 129–34.

- ^ a b c Burrows 1998, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d Wade, Mark. "Atlas". Encyclopedia Astronautix. Archived from the original on July 10, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- JSTOR 25162945.

- ^ "Atlas Missiles and Space Launchers | Historic Spacecraft". historicspacecraft.com. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "How Much Do You Know About the History and Invention of WD-40?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "WD-40 History | Learn the Stories Behind the WD-40 Brand | WD-40". www.wd40.com. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8229-7746-9. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "OhioLINK Institution Selection". Ebooks.ohiolink.edu. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Schefter 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Schefter 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Schefter 1999, pp. 15–18.

- ^ a b Cadbury 2006, pp. 154–57.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2003a, p. 151.

- ^ Siddiqi 2003a, p. 155.

- NASA History Website.

- ^ Hardesty & Eisman 2007, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c Siddiqi 2003a, pp. 163–68.

- ^ a b c Cadbury 2006, p. 163.

- ^ a b Hardesty & Eisman 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Cadbury 2006, pp. 164–65.

- ^ a b "Sputnik 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "60 years ago: The First Animal in Orbit - NASA". November 6, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Analysis of Soviet Earth Satellite and Launching Device" (PDF). November 9, 1957. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Mark Wade. "Atlas A". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Gröttrup, Helmut (April 1958). Aus den Arbeiten des deutschen Raketen-Kollektivs in der Sowjet-Union [About the work of the German rocketry collective in the Soviet Union]. Raketentechnik und Raumfahrtforschung (in German). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Raketentechnik und Raumfahrt. pp. 58–62.

Towards the end of the war the general opinion was that a starting acceleration of 2 g was optimal. We have carried out detailed studies on this point, taking into account the increase in engine weights and the weights of the components used to transmit thrust. It turned out that a starting acceleration of a considerably smaller value can be optimal. One of our projects was designed for a starting acceleration of 1.4 g.

- ^ "Development of guided missiles at Bleicherode and Institut 88". CIA Historical Collections. January 22, 1954. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

It was generally held up to now that the ratio thrust/take-off weights should be approximately two. [Gröttrup] discovered … that values as low as 1.2 for this ratio could give optimum results under certain conditions.

Remark: The designations R-12 und R-14 are related to the internal project names (also known as G-2 und G-4), not to the rockets installed during the Cuban Missile Crisis - ISBN 978-0-7910-9357-3.

- ^ Brzezinski 2007, pp. 254–67.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Terry. The Nuclear Age. San Diego: Greenhaven, Inc., 2002.(146)

- ^ Knapp, Brian. Journey into Space. Danbury: Grolier, 2004.(17)

- ^ Barnett, Nicholas. '"Russia Wins Space Race": The British Press and the Sputnik Moment', Media History, (2013) 19:2, 182–95.

- ^ "THE NATION: Red Moon Over the U.S." TIME. October 14, 1957. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c Nicogossian, Arnauld E. (1993). Space Biology and Medicine: Space and Its Exploration. Washington, DC.: American Institute of Aeronautics. p. 285.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-5330-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-8160-5330-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Explorer 2 - Earth Missions - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Explorer 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Explorer 3 - Earth Missions - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Birth of NASA". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ Bilstein, Roger E. "2. Aerospace Alphabet: ABMA, ARPA, MSFC". Stages to Saturn. Washington D.C.: NASA. p. 39. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Beginnings of Research in Space Biology at the Air Force Missile Development Center, 1946-1952". NASA. January 1958. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ DE Beischer and AR Fregly (1962). "Animals and man in space. A chronology and annotated bibliography through the year 1960". US Naval School of Aviation Medicine. ONR TR ACR-64 (AD0272581). Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ "First dog in space died within hours". BBC. October 28, 2002. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Berger, Eric (November 3, 2017). "The first creature in space was a dog. She died miserably 60 years ago". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ISBN 1-59643-302-7

- ^ Siddiqi 2018, p. xv.

- ^ Siddiqi 2018, p. 14.

- ^ NASA. "Pioneer 0, 1, 2". Archived from the original on January 31, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Hess, Wilmot (1968). The Radiation Belt and Magnetosphere.

- Asif Siddiqi (October 12, 2015). "Declassified documents offer a new perspective on Yuri Gagarin's flight". Archivedfrom the original on December 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hall & Shayler 2001, pp. 149–57.

- ^ Gatland 1976, p. 254.

- ^ "Soviet Space Deceptions - not so many after all!". www.svengrahn.pp.se. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ Pervushin (2011), 7.1 Гражданин мира

- ^ Государственная Дума. Федеральный закон №32-ФЗ от 13 марта 1995 г. «О днях воинской славы и памятных датах России», в ред. Федерального закона №59-ФЗ от 10 апреля 2009 г «О внесении изменения в статью 1.1 федерального закона "О днях воинской славы и памятных датах России"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Российская Газета", No. 52, 15 марта 1995 г. (State Duma. Federal Law #32-FZ of March 13, 1995 On the Days of Military Glory and the Commemorative Dates in Russia, as amended by the Federal Law #59-FZ of April 10, 2009 On Amending Article 1.1 of the Federal Law "On the Days of Military Glory and the Commemorative Dates in Russia". Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- ^ "UN Resolution A/RES/65/271, The International Day of Human Space Flight (12 April)". April 7, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Hall & Shayler 2001, pp. 183, 192.

- ^ Gatland 1976, pp. 117–18.

- ^ Hall & Shayler 2001, pp. 185–91.

- ^ a b Hall & Shayler 2001, pp. 194–218.

- ^ "Kamanin diaries, April 16, 1965". Astronautix.com. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Burgess & Hall 2009, p. 229.

- ^ Eidelman, Tamara (2013). "A Cosmic Wedding". Russian Life. 56 (6): 22–25.

- OCLC 930799309.

- ^ "In the Beginning: Project Mercury - NASA". October 1, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 150.

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 47.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 490.

- ^ Schefter 1999, pp. 138–43.

- ^ Gatland 1976, pp. 153–54.

- OCLC 709678549. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (July 22, 2021). "A New Analysis May Have Just Solved A Decades-Old Mystery Of The Space Race". NPR. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Schefter 1999, pp. 156–164.

- ^ "President John F. Kennedy Pins NASA Distinguished Service Medal on John Glenn". NASA. May 13, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ISBN 1-85233-406-1.

- ^ Quoted in John M. Logsdon, The Decision to Go to the Moon: Project Apollo and the National Interest (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970) p. 111.

- ^ David E. Bell, Memorandum for the President, "National Aeronautics and Space Administration Budget Problem", March 22, 1961, NASA Historical Reference Collection; U.S. Congress, House, Committee of Science and Astronautics, NASA Fiscal 1962 Authorization, Hearings, 87th Cong., 1st. sess., 1962, pp. 203, 620; Logsdon, Decision to go to the Moon, pp. 94–100.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Picador, 1979.(179)

- ^ Roger D. Launius and Howard E. McCurdy, eds, Spaceflight and the Myth of Presidential Leadership (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 56.

- ^ Kennedy to Johnson,"Memorandum for Vice President," Archived January 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine April 20, 1961.

- ^ von Braun, Wernher (April 29, 1961). "Memo, Wernher von Braun to the Vice President of the United States" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2005. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon B. (April 28, 1961). "Memo, Johnson to Kennedy, Evaluation of Space Program" (PDF). Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Kennedy, John F. (September 12, 1962). "Address at Rice University on the Nation's Space Effort". Historical Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; French, Francis. "Imagining a World Where Soviets and Americans Joined Hands on the Moon". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-78021-000-1.

- ^ a b c "THE SOVIET MANNED LUNAR PROGRAM". spp.fas.org. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ "Yes, There Was a Moon Race". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ "Address before the 18th General Assembly of the United Nations, September 20, 1963". JFK Library. September 20, 1963. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

Finally, in a field where the United States and the Soviet Union have a special capacity—in the field of space—there is room for new cooperation, for further joint efforts in the regulation and exploration of space. I include among these possibilities a joint expedition to the moon. Space offers no problems of sovereignty; by resolution of this Assembly, the members of the United Nations have foresworn any claim to territorial rights in outer space or on celestial bodies, and declared that international law and the United Nations Charter will apply. Why, therefore, should man's first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition? Why should the United States and the Soviet Union, in preparing for such expeditions, become involved in immense duplications of research, construction, and expenditure? Surely we should explore whether the scientists and astronauts of our two countries—indeed of all the world—cannot work together in the conquest of space, sending someday in this decade to the moon not the representatives of a single nation, but the representatives of all of our countries.

- ^ Stone, Oliver and Peter Kuznick, "The Untold History of the United States" (Gallery Books, 2012), p. 320

- ^ a b Sietzen, Frank (October 2, 1997). "Soviets Planned to Accept JFK's Joint Lunar Mission Offer". "SpaceCast News Service" Washington DC. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ Sagdeev, Roald; Eisenhower, Susan (May 28, 2008). "United States-Soviet Space Cooperation during the Cold War". Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- .

- ^ "Report on the Activities of the COSPAR Working Group VII". Preliminary Report, COSPAR Twelfth Plenary Meeting and Tenth International Space Science Symposium. Prague, Czechoslovakia: National Academy of Sciences. May 11–24, 1969. p. 94.

- ^ Siddiqi 2018, p. 41.

- ^ "National Space Science Data Center – Ranger 6". National Air and Space Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ "Luna 9". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 10". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 12". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 3 photography". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Lunar Orbiter to the Moon (1966 - 1967)". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Lunar Orbiter Program - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. September 11, 2023. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ a b "Luna 13". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "The Mission of Luna 13: Christmas 1966 on the Moon". Drew Ex Machina. December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "USSR - Luna 13". www.orbitalfocus.uk. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Luna E-6M". www.astronautix.com. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 1 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 1 - Moon Missions - NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 3 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Astronauts Pay a Visit to Surveyor 3 - NASA". Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 6 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 6". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venus: Exploration - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. November 9, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mariner 1 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 8, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Mariner 2 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 20, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Mariner 2". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mariner 5 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 20, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Loff, Sarah (October 21, 2013). "Gemini: Stepping Stone to the Moon". Gemini: Bridge to the Moon. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ Siddiqi 2003a, p. 383.

- ^ a b c Siddiqi 2003a, pp. 384–86.

- ^ Schefter 1999, p. 149.

- ^ Schefter 1999, p. 198.

- The Toronto Star. Toronto: Torstar. UPI. p. 1.

- ^ a b Schefter 1999, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Tanner, Henry (March 19, 1965). "Russian Floats in Space for 10 Minutes; Leaves Orbiting Craft With a Lifeline; Moscow Says Moon Trip Is 'Target Now'". The New York Times. New York. p. 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2003a, p. 448.

- ^ a b Schefter 1999, p. 205.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2003a, pp. 454–460.

- The Toronto Star. Toronto: Torstar. p. 11.

- ^ Siddiqi 2003a, pp. 510–11.

- ^ Schefter 1999, p. 207.

- ^ "The World's First Space Rendezvous". Apollo to the Moon; To Reach the Moon – Early Human Spaceflight. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2006.

- ^ Gatland 1976, p. 176.

- ^ "Gemini8 Crew and PJs". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ "Gemini Pioneered the Technology Driving Today's Exploration - NASA". March 27, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Lindroos, Marcus (1997). "The Soviet Manned Lunar Program". FAS. Federation of American Scientists (FAS). Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Portree 1995, p. 3-5.

- ISBN 978-0-471-32721-9.

- ^ a b c Avilla, Aeryn (February 21, 2020). "N1: The Rise and Fall of the USSR's Moon Rocket". SpaceflightHistories. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ "Ground Ignition Weights". NASA.gov. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Portree 1995, p. 12-13.

- ^ Heintze, Hans-Joachim (March 5, 1999). "Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and International Law". International Network of Engineers and Scientists Against Proliferation. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008.

- ^ Google books Nuclear Weapons and Contemporary International Law N. Singh, E. WcWhinney (p. 289)

- ^ UN website UN Resolution 1348 (XIII). Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space". United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

- ^ Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. National Security Files. Subjects. Space activities: US/USSR cooperation, 1961–96

- ^ Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies: Status of the Treaty (UNODA)

- ^ a b "THE HISTORY OF US ANTI-SATELLITE WEAPONS" (PDF). man.fas.org.

- ^ "The Historic Beginnings Of The Space Arms Race". www.spacewar.com. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ RBTH; Novosti, Yury Zaitsev, RIA (November 1, 2008). "The historic beginnings of the space arms race". Russia Beyond. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MilsatMagazine". www.milsatmagazine.com. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "The Hidden History of the Soviet Satellite-Killer". Popular Mechanics. November 1, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "istrebitel-sputnikov-is". weaponsandwarfare.com. August 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "SAINT". August 20, 2016. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c Seamans, Robert C. Jr. (April 5, 1967). "Findings, Determinations And Recommendations". Report of Apollo 204 Review Board. NASA History Office. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2007.

- Chris Kraft and Bob Gilruthseconded.

- ^ "soyuz-1" (PDF). sma.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Vladimir Komarov's tragic flight aboard Soyuz-1". www.russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "Soyuz 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Spaceflight mission report: Soyuz 1". www.spacefacts.de. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "Soyuz 1". August 20, 2016. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ Stilwell, Blake (April 2, 2018). "The first man to die in the Space Race cursed the USSR the whole way down". We Are The Mighty. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ Harvey, Ian (October 26, 2015). "US Analysts Heard Russian Astronaut Komarov cursing his superiors while he plunged to his death in 1967 | The Vintage News". thevintagenews. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "A Cosmonaut's Fiery Death Retold : Krulwich Wonders... : NPR". NPR. May 3, 2019. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ Margaritoff, Marco (May 5, 2023). "The Tragic Death Of Vladimir Komarov, The Man Who Fell From Space". All That's Interesting. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ Cadbury 2006, pp. 310–12, 314–16.

- ^ Burrows (1999), p. 417

- ^ Murray & Cox 1990, pp. 323–24.

- ^ a b c d Hall & Shayler 2003, pp. 144–47.

- ^ "Soyuz 4 & 5: The First Crew Exchange in Space". drewexmachina. January 17, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2022.