Tibesti Mountains

| Tibesti | |

|---|---|

Bardaï | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Emi Koussi |

| Elevation | 3,415 m (11,204 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 19°48′N 18°32′E / 19.8°N 18.53°E[1] |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 480 km (300 mi) |

| Width | 350 km (220 mi) |

| Area | 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| Countries | Chad and Libya |

| Range coordinates | 20°46′59″N 18°03′00″E / 20.783°N 18.05°E |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Oligocene |

| Type of rock | Andesite, Basalt, Basanite, Dacite, Ignimbrite, Rhyolite, Trachyandesite and Trachyte |

The Tibesti Mountains are a

has shaped volcanic spires and carved an extensive network of canyons through which run rivers subject to highly irregular flows that are rapidly lost to the desert sands.Tibesti, which means "place where the mountain people live", is the domain of the

, the supply of which is highly variable from year-to-year and decade-to-decade. The plateaus are used to graze livestock in the winter and harvest grain in the summer. Temperatures are high, although the altitude ensures that the range is cooler than the surrounding desert. The Toubou, who were settled in the range by the 5th century BC, adapted to these conditions and turned the range into a large natural fortress. They arrived in several waves, taking refuge in times of conflict and dispersing in times of prosperity, although not without intense internal hostility at times.The Toubou came into contact with the

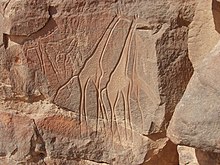

who first entered the range in 1914 and took control of the area in 1929. The independent spirit of the Toubou and the geopolitics of the region has complicated the exploration of the range as well as the ascent of its peaks. Tensions continued after Chad and Libya gained independence in the mid-20th century, with hostage-taking and armed struggles occurring amid disputes over the allocation of natural resources. The geopolitical situation and the lack of infrastructure has hampered the development of tourism.The Saharomontane flora and fauna, which include the rhim gazelle and Barbary sheep, have adapted to the mountains, yet the climate has not always been as harsh. Greater biodiversity existed in the past, as evidenced by scenes portrayed in rock and parietal art found throughout the range, which date back several millennia, even before the arrival of the Toubou. The isolation of the Tibesti has sparked the cultural imagination in both art and literature.

Toponymy

The Tibesti Mountains are named for the Toubou people, also written Tibu or Tubu, that inhabit the area. In the Kanuri language, tu means "rocks" or "mountain" and bu means "a person" or "dweller," and thus Toubou roughly translates to "people of the mountains"[a] and Tibesti to the "place where the mountain people live".[2][3]

Most of the mountain names are derived from

Geography

Location

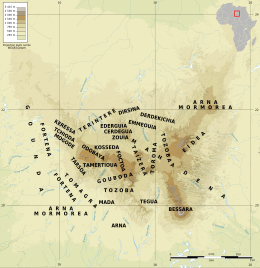

The mountains lie on the border between

The range is 480 km (300 mi) in length, 350 km (220 mi) in width,[14] and spans 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi).[15][16] It draws a large triangle with sides of 400 km (250 mi)[12] and vertices facing south, northwest and northeast in the heart of the Sahara,[17][18] making it the largest mountain range of the desert.[19]

Topography

The highest peak in the Tibesti Mountains, as well as the highest point in Chad and the Sahara Desert, is the 3,415-meter (11,204 ft) Emi Koussi, located at the southern end of the range.[18] Other prominent peaks include Pic Toussidé[c] at 3,296 m (10,814 ft) and the 3,012-meter (9,882 ft) Timi on its western side, the 2,972-meter (9,751 ft) Tarso Yega, the 2,925-meter (9,596 ft) Tarso Tieroko, the 2,849-meter (9,347 ft) Ehi Mousgou, the 2,845-meter (9,334 ft) Tarso Voon, the 2,820-meter (9,250 ft) Ehi Sunni, and the 2,774-meter (9,101 ft) Ehi Yéy near the center of the range.[20] The 3,376-meter (11,076 ft) Mouskorbé is a peak notable for its height in the northeastern part of the mountain range.[11][21] The 2,266-meter (7,434 ft) Bikku Bitti, the highest point in Libya, is nearby, on the other side of the border.[11][22] The average elevation of the Tibesti Mountains is about 2,000 m (6,600 ft); sixty percent of its area exceeds 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in elevation.[18]

The range includes five

- The other four shield volcanoes of the Tibesti Mountains

-

Satellite image of Tarso Toon (top right) and Ehi Yéy (bottom left)

-

Satellite image of Tarso Voon

-

False-color satellite image of Tarso Yega (top)

-

Satellite image ofTarso Toussidé showing Pic Toussidé (the center of the dark spot) and Trou au Natroncrater (bottom right)

The rest of the Tibesti Mountains consists of

Hydrology

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya, while the southern half belongs to the endorheic basin of Lake Chad. However, none of the rivers travel long distances, as the water evaporates in the desert heat or seeps into the ground, although the latter may flow great distances through subterranean aquifers.[33]

The wadis in the Tibesti are called enneris.[34] The water mainly originates from the storms that periodically rage over the mountains.[35][36] Their flow is highly variable.[37] For example, the largest wadi, named Bardagué (or Enneri Zoumeri on its upstream portion) and located in the northern part of the range, recorded a flow of 425 m3/s (15,000 cu ft/s) in 1954, yet over the next nine years it experienced four years of total drought, four years of flow less than 5 m3/s (180 cu ft/s) and one year where three different flow rates were measured: 4, 9 and 32 m3/s (140, 320 and 1,130 cu ft/s).[38]

Other major rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the Serir Tibesti, while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an 1,800-meter (5,900 ft) high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east.[12][39] The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some 400 km (250 mi) southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the Bodélé Depression, as does Enneri Miski a little further to the east, along with other wadis such as the Enneri Korom and Enneri Aouei.[34] Several rivers flow radially on the southern slopes of the Emi Koussi before seeping into the sands of Borkou and then reemerging at escarpments up to 400 km (250 mi) south of the summit, near the Ennedi Plateau.[40]

At the bottom of many canyons are

The Yi Yerra hot springs is located on the southern flank of Emi Koussi at about 850 m (2,800 ft) elevation.[1][42] Water emerges from the springs at 37 °C (99 °F).[18] A dozen hot springs are also located at the Soborom geothermal field on the northwest side of Tarso Voon, where water emerges at temperatures ranging between 22 and 88 °C (72 and 190 °F).[18][23]

Geology

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of

The

Geomorphology

Volcanic activity in the Tibesti took place in several phases. In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions. In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast tarsos, as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast. Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon, Tarso Tieroko and Ehi Yéy; the collapse of these structures formed the first calderas. This phase also saw the formation of the Bounaï lava dome and Tarso Voon. To the east, the lava flows formed the large plateaus of Tarso Emi Chi, Tarso Ahon and Tarso Mohi. Emi Koussi increased in height. The fourth phase saw the formation of Tarso Toussidé and the lava flows of Tarso Tôh in the west, the collapse of the caldera on the summit of Tarso Voon and associated ejecta deposits in the center, and the decline in lava production in the east, with the exception of Emi Koussi, which continued to rise. In the fifth phase, volcanic activity became much more localized and lava production continued to wane. Calderas formed on top of Tarso Toussidé and Emi Koussi, and the lava domes Ehi Sosso and Ehi Mousgou appeared. Finally, in the sixth phase, Pic Toussidé formed on the western rim of several pre-Trou au Natron calderas, along with new lava flows, including Timi on the northern slope of Tarso Toussidé. With scarce time for erosion, these lava flows have a dark, youthful appearance.[56]

The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi.[57] Presently,[update] there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé.[18][23][26] Carbonate deposits in the Trou au Natron and Era Kohor craters are also representative of more recent volcanic activity.[26]

The study of

Climate

The Tibesti climate is substantially less dry than that of the surrounding

The average monthly maximum temperature is 28 °C (83 °F) in the central Tibesti Mountains, while the average monthly minimum is 12 °C (53 °F).

| Climate data for the central Tibesti Mountains (21°15′N 17°45′E / 21.250°N 17.750°E), approximately 1,200 m (3,900 ft) elevation, 1901–2009 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.5) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

29.8 (85.7) |

34.2 (93.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34 (94) |

33.1 (91.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

28.1 (82.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

12.8 (55.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21 (70) |

25.3 (77.6) |

27.3 (81.2) |

27 (81) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.1 (77.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

15.1 (59.1) |

11.6 (52.8) |

19.9 (67.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.1 (46.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.9 (55.3) |

7.4 (45.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

11.8 (53.3) |

| Source 1: Global Species[69] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: University of East Anglia Climatic Research Unit[71] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Much like an island surrounded by ocean, the

Flora

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing

Around the edge of the Tibesti, where the canyons exit the range, are

Saharomontane

The vegetation above 2,600 meters (8,500 feet) consists of dwarf shrubs, which are generally limited to 20 to 60 cm (8 to 24 in) in height and do not exceed one meter (3 ft). The shrubbery consists of the species

Fauna

Many resident birds can be found in the Tibesti. These include the crowned sandgrouse (Pterocles coronatus), bar-tailed lark (Ammomanes cincturus), blackstart (Oenanthe melanura syn. Cercomela melanura), desert lark (Ammomanes deserti), desert sparrow (Passer simplex), fulvous babbler (Argya fulva), greater hoopoe-lark (Alaemon alaudipes), Lichtenstein's sandgrouse (Pterocles lichtensteinii), pale crag martin (Ptyonoprogne obsoleta), trumpeter finch (Bucanetes githagineus) and the white-crowned wheatear (Oenanthe leucopyga).[90]

The gueltas are flushed periodically each year by stormwater, maintaining low

Population

The town of Bardaï, located on the northern flank of the mountains at an elevation of 1,020 m (3,350 ft), is the capital of the Tibesti region.

The vast majority of the population is

Traditional Toubou life is punctuated by the seasons, divided between

History

Human settlement

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when denser paleovegetation facilitated human habitation.[60] The Toubou were settled in the region by the 5th century BC and eventually established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization.[110][111] Around this time, Herodotus mentioned the Toubou, whom he labeled "Aethiopians", and described them as having a language akin to the "cry of bats".[f][110][113]

Herodotus further remarked on a conflict between the Toubou and the civilization of

In the 12th century, the geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi spoke of a "country of Zaghawa negroes", or camel herders, that had converted to Islam. The historian Ibn Khaldun described the Toubou in the 14th century.[118] In the 15th and 16th centuries, Al-Maqrizi and Leo Africanus referred to the "country of the Berdoa", meaning Bardaï, the former associating the Toubou with the Berbers and the latter describing them as Numidian relatives of the Tuareg.[119]

The Toubou settled in the Tibesti in several waves. Generally, newcomers either killed or absorbed the previous clans after battles that were often both long-lasting and bloody.

There is evidence of early Daza settlements in the Tibesti; however, these early clans—the Goga, Kida, Terbouna and Obokina—were assimilated into later Daza clans, who arrived in the Tibesti between the 15th and 18th centuries, possibly having fled the

Several clans with traditions similar to those of the Donzas of the Borkou region, south of the Tibesti, settled in the range in the 16th and 17th centuries. These include the Keressa and Odobaya in the west, Foctoa in the northwest and northeast, and Emmeouia in the north. Several other clans—the Mogode in the west, Terintere in the north, Tozoba in the center, and Tegua and Mada in the south—are originally clans of the

The early 17th century also saw the arrival of three clans from the region of

The Tuareg people intermixed with the Toubou clans, especially with the early Goga clan, which produced the Gouboda, and with the later Arna clan, which produced the Mormorea. In both instances, the new clans were placed under the authority of

Regional relations and colonization

In the mid-19th century the

While the Italians occupied the Fezzan, a French column entered the Tibesti in early 1914 from Kaouar.[131][132] The region was at the heart of a dispute between the colonial powers,[17] with the Italian Empire to the north and French West Africa to the south. During World War I, a Senussi revolt forced the Italians to temporarily withdraw from the Fezzan and the northeastern part of the Tibesti.[131] Likewise, fierce resistance from the Toubou forced the French troops to retreat southward from the Tibesti in 1916.[133] After a period of internal disorder, the Tibesti was reconquered by the French colonial empire in 1929, and the region was placed under the administration of French Equatorial Africa.[113][133][134] Libya gained its independence from Italy in 1947, and was released from British and French oversight in 1951.[135]

Modern history

Chadian Civil War

Chad gained independence from France in 1960, and in 1965 the Chadian government led by

In 1968, the French Army, at the request of Tombalbaye, intervened in an attempt to put an end to the rebellion. However, French General Edouard Cortadellas admitted their attempts to quell the Toubou were essentially hopeless, remarking, "I believe we should draw a line below [the Tibesti region] and leave them to their stones. We can never subdue them." The French therefore focused their intervention on the center and east of the country, leaving the Tibesti region largely alone.[139][140]

In 1969,

Another rift formed between Goukouni and Habré, which by 1976 had spread to the Second Liberation Army, leaving one side commanded by Habré and the other commanded by Goukouni and supported by Libya.[145][146] In June 1977, Goukouni's forces attacked the Chadian government stronghold in Bardaï.[147][148] The rebels also attacked Zouar. These battles resulted in the death of 300 government troops.[147] Bardaï surrendered to the rebels on July 4, while Zouar was evacuated.[147] The Chadian government, led by Félix Malloum since Tombalbaye's overthrow in 1975, signed a peace agreement with Habré in 1978, although fighting with other rebel groups, many aligned with Libya, continued.[147][149]

Tibesti War

In 1978, war broke out between Chad and Libya ostensibly over the Aouzou Strip, a 114,000-square-kilometer (44,000 sq mi) borderland between Chad and Libya that extends into the Tibesti Mountains and is rumored to contain uranium deposits.[113][150][151][152] In 1980, Libya used the strip as a base from which stage an attack, led by Goukouni, on the Chadian capital, N'Djamena, located in southern Chad and controlled by Habré.[153] N'Djamena was toppled in December; however, under considerable international pressure, Libya withdrew from southern Chad in late 1981, and Habré's Armed Forces of the North (FAN) took control of the entirety of Chad with the exception of the Tibesti, where Goukouni retreated with his Libyan-backed Government of National Unity (GUNT) forces.[153][154][155] Goukouni then established a National Peace Government in Bardaï and proclaimed it the legitimate government of Chad. Habré attacked the GUNT in the Tibesti in both December 1982 and January 1983 but was repelled on both occasions. Although fighting intensified over the next several months, the mountains remained under the control of the GUNT and Libyan forces.[156]

By 1986, following a series of military defeats, the GUNT had begun to disintegrate along with relations between Goukouni and Libya.

MDJT War

Following a decade of relative peace, in late 1997 the Tibesti saw the formation of the

Between 1998 and 2010 the MDJT had established a weak government in the Tibesti region, functionally independent from that of Chad.[169] In 2002, however, weakened by its isolation in the Tibesti and from a series of military defeats, the MDJT split into several factions following the death of its leader, Youssouf Togoïmi.[170] In 2005, under pressure from Libya, the "most legitimate" MDJT faction signed a peace agreement with the Chadian government, yet the war continued, albeit at a lower intensity.[171] From 2009 to 2010, the last of the MDJT rebels surrendered to the Chadian government.[172] The legacy of decades of war continues to burden the Tibesti with a lack of government, a warrior culture, and a landscape strewn with thousands of landmines.[17][169]

Gold rush

Gold was discovered in the Tibesti Mountains in 2012, attracting prospectors from across the

Scientific exploration and research

Due to its isolation and geopolitical situation, the Tibesti Mountains were long unexplored by scientists.

Although the Tibesti is one of the world's most significant examples of intracontinental volcanism, ongoing political instability and the presence of landmines means that, today, geologic research often must be conducted on the basis of satellite images and comparison with research on Martian volcanoes.

Climbing history

Although not an alpine climb, Gustav Nachtigal ascended to 2,400 m (7,873 ft) elevation as he traversed a

In 1957, Peter Steele led a University of Cambridge expedition that sought to conquer Tarso Tieroko, which Thesiger had described as "probably the most beautiful peak in Tibesti".[190] After climbing two peaks situated on a ridge to the north,[i] they attempted Tieroko, but just 60 m (200 ft) from the summit, they were faced with a vertical, crumbling rock wall and were forced to descend. Following this defeat, they took the opportunity to climb Emi Koussi, 19 years after its first ascent by Thesiger, and also Pic Woubou, a prominent spire located between Bardaï and Aouzou.[191] Seven years later, in 1965, a team led by the Englishman Doug Scott succeeded in climbing Tieroko.[192]

In 1963, an expedition under the Italian Guido Monzino ascended a peak in the massif of the Aiguilles of Sissé which, despite rising only 800 ft (240 m) above ground level, proved "very difficult".[193] The Englishman Eamon "Ginge" Fullen scaled Bikku Bitti, the highest peak in Libya at 2,266 m (7,434 ft), in 2005, capping a successful Guinness World Records attempt.[22][194] Due to the unstable political situation, mountaineering in the Tibesti remains a challenging endeavor today.[195]

Economy

Natural resources

Although gold was long known to exist in small quantities, substantial deposits were discovered in 2012.[196][197] Diamonds have also been found. The mountains and their surroundings could contain significant quantities of uranium, tin, tungsten, niobium, tantalum, beryllium, lead, zinc and copper.[197] Amazonite is present and was reportedly mined by the ancient Libyan civilization of Garamantes.[198][199][200] Salt is mined today, and is an important source of income for the Toubou.[99]

The Soborom geothermal field, the name of which means "healing water",[j] is known to locals for its medicinal qualities; its pools are rumored to cure dermatitis and rheumatism after several days of soaking.[8] As of the latest analysis, in 1992,[update] Mare de Zoui and its surroundings were rarely visited, aside from a nearby oasis. However, there are numerous small oases on the plains of Borkou, near Emi Koussi, which are extensively exploited. This water is thought to be sourced from the Tibesti Mountains, from where it flows underground before surfacing at these springs.[40]

Agriculture

There are accessible

Tourism

As the Sahara's highest mountain range, with geothermal features, a distinctive culture, and numerous rock and parietal artworks, the Tibesti has tourism potential.

As of 2017,[update] there are essentially only two tour operators in Chad, run by Chadians and Italians and both based in N'Djamena, which offer all the tours that exist in Chad, including trips to the Tibesti.[207] Tours are typically multi-week affairs, with tourists accommodated in tents.[208][211] They include exposure to Toubou cultural traditions and to the Tibesti's rock and parietal art.[208] Continuing civil unrest and the presence of landmines pose a danger to tourists, and, despite the occasional tour group, the Tibesti remains one of the most isolated places on Earth.[17][208][212]

Conservation

The resources available for conservation in the Tibesti are limited.[66] In 2006, various non-governmental working groups proposed a protected area to preserve the area's rhim gazelle and Barbary sheep populations.[81][82] The protected area would be modeled after the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Faunal Reserve to the south. However, due to economic and political barriers, the project has not moved beyond the proposal stage.[213] Nevertheless, the establishment of two World Heritage Sites[k] in northern Chad in 2012 and 2016 has renewed hope that a similar feat might be achieved in the Tibesti.[207]

Art and literature

Rock and parietal art

The Tibesti Mountains are renowned for their

Other engravings portray warriors dressed in feathers or spiked ornaments and armed with bows, shields,

Other works

The Tibesti Mountains have inspired several contemporary works of art and literature. The volcanic spires of the Tibesti, along with a stylized sheep's head, were displayed on a 20 CFA franc postage stamp issued by Republic of Chad in 1962.[218] In 1989, French painter and sculptor Jean Vérame used the natural surroundings of the Tibesti to create multidimensional land art works by painting rocks.[219][220]

The Tibesti range was featured in the 1958 short story "Le Mura di Anagoor" ("The Walls of Anagoor") by the Italian novelist Dino Buzzati.[l] In the story, a local guide offers to show a traveler the walls of a great city that is absent from the maps. The city is exceedingly opulent, yet exists in total autarky and does not submit to higher authority. The traveler waits many years, in vain, to enter the Tibesti city.[221][223]

Notes and references

Notes

- Toubou communicate by whistling or because they run fast.[2]

- ^ Temperatures in the Tibesti can drop to −10 °C (14 °F).[9]

- Tarso Toussidé.[7]

- ^ It is unlikely that the earlier vegetation was significantly qualitatively different from that which exists today, although Mediterranean flora would have been somewhat more common.[60]

- ^ Herodotus described "Aethiopian troglodytes", located "ten days" from Awjila near a "mound of salt, water and palm trees", being pursued by four-horsed chariots of the civilization of Garamantes.[112] Chapelle (1982, p. 36) reasons that these were the Toubou, as troglodytes are by definition cave dwellers, the only caves near the described location are those of the Tassili n'Ajjer and the Tibesti, and the ergs neighboring the Tassili n'Ajjer are unsuitable for chariots, while the flat regs surrounding the Tibesti would have allowed chariots to pursue those who came to plunder the palm groves.

- ^ According to Oliver (1975, p. 290), this populace was "in all probability" the Toubou.

- ^ Le Cœur was killed in action in Italy in 1944.[182]

- ^ The two peaks are "The Imposter" and "Hadrian's Peak."[190]

- ^ At least one other source reports that the name instead means "boiling water".[201]

- ^ Lakes of Ounianga[214] and the Ennedi Plateau[215]

- ^ Although the plot of "Le Mura di Anagoor" takes place in the Tibesti,[221] at least one English translation has moved it to Tibet.[222]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Emi Koussi". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Room 2006, p. 375.

- ^ Shoup 2011, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 611.

- ^ Salam, Hammuda and Eliagoubi 1991, p. 1155.

- ^ Sola and Worsley 2000, p. xi.

- ^ a b c Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 615, 619.

- ^ a b Beauvilain 1996, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 3.

- ^ a b Braquehais 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Google. "Google Earth" (Map). Google Earth. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Roure 1939, p. 1.

- ^ Grove 1960, p. 18.

- ^ a b Bosworth 2012.

- ^ Gourgaud and Vincent 2004, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 609.

- ^ a b c d e Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 610.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Baldur 2018, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 615–616.

- ^ Hellmich 1972, p. 10.

- ^ a b Braun and Passon 2020, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Beauvilain 1996, pp. 15–20.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 609, 615–616, 620–621.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 615.

- ^ a b c d e f g Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 619.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 611, 614.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 609, 611, 615.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 1–2, 18–20.

- ^ Grove 1960, p. 23.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 68–70, 184.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 67.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 18.

- ^ a b Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Grove 1960, pp. 23, 25.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 1–2, 18.

- ^ a b Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 3, 18.

- ^ "Emi Koussi: Synonyms and Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Tarso Tôh". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 611, 616, 619.

- ^ Pegram et al. 1976, p. 127.

- ^ El Makkrouf 1988, p. 964.

- ^ Suayah 2006, p. 568.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 611–612.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 611, 616.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 609, 616, 619.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 619–620.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 621.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 611, 619.

- ^ El Makkrouf 1988, p. 951.

- ^ "Tarso Toussidé". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 615, 617–619.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 617–619.

- ^ Hagedorn 1997, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Hagedorn 1997, p. 267.

- ^ a b Hagedorn 1997, p. 273.

- ^ Hagedorn 1997, pp. 268–270, 273.

- ^ Soulié-Märsche et al. 2010, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Maley 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Tourte 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b Musch 2021, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Messerli 1973, p. A143.

- ^ Messerli 1973, p. A140.

- ^ a b c "Climate Data for Latitude 21.25 Longitude 17.75". Global Species. July 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017.

- ^ Musch 2021, p. 3.

- ^ "Climatic Research Unit (CRU) time-series datasets of variations in climate with variations in other phenomena". University of East Anglia Climatic Research Unit. February 14, 2017. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017.

- ^ Mies and Lösch 1995, p. 192.

- ^ White 1998, p. 243.

- ^ Giazzi 1996, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f White 1998, pp. 243–244.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b c Schultze-Motel 1969, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 19.

- ^ Mies and Lösch 1995, p. 196.

- ^ Kappen 1973, p. 311.

- ^ a b Beudels 2008.

- ^ a b Baseline Study 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Camps-fabrer 1999.

- ^ Ginsberg and Macdonald 1990, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Roos et al. 2021, pp. 410, 415.

- ^ Benda et al. 2014, pp. 10, 34, 126.

- ^ a b Geniez 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Animals Committee 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Salvador 1996, p. 1.

- ^ "Tibesti Massif". BirdLife International. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Azevedo and Decalo 2018, p. 495.

- ^ a b c Ministère des Affaires étrangères 2016.

- ^ Tilho 1920.

- ^ Thompson 2020.

- ^ Mahjoub 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 6.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c d e f Chapelle 1982, pp. 72–79.

- ^ Baroin 1985, p. 75.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 2, 38, 407.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 32, 106.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, chpts. 4, 5.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chapelle 1982, p. 70.

- ^ a b Chapelle 1982, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Beck and Huard 1969, p. 228.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d Roure 1939, p. 2.

- ^ Oliver 1975, p. 286.

- ^ a b Huß 2006.

- ^ Desanges 1964, p. 713.

- ^ Oliver 1975, p. 290.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 8, 54.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 9.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, chpt. 2 sect. 1.

- ^ a b c d Collelo 1990.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 41.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 41–44, 72–79.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, p. 334.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 61–64, 93–97.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 64, 96, 107.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, p. 342.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, p. 341.

- ^ a b c Chapelle 1982, p. 64.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, pp. 346–347, 357.

- ^ a b Ricciardi 1992, p. 358.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 2, 64.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, pp. 364–365, 371.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, pp. 4, 12.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b Arsenault 2006.

- ^ a b Correau 2008.

- ^ "Zum Weinen" 1975.

- ^ a b Henderson 1984, chpt. II.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Higgins 1993, p. 18.

- ^ Arnold 2009, p. 286.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Jacobs 2011.

- ^ Metz 1989, p. 55.

- ^ Ricciardi 1992, p. 305.

- ^ a b Metz 1989, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, p. 186–188.

- ^ Henderson 1984, Chpt. III.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, p. 188.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Fearon, Laitin and Kasara 2006, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Pollack 2004, loc. 5452.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, p. xii.

- ^ Pollack 2004, locs. 5452–5457.

- ^ a b Pollack 2004, loc. 5457.

- ^ Nolutshungu 1995, pp. 230, 245.

- ^ Pollack 2004, locs. 5457–5462.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 38.

- ^ a b Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 43.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 37, 48, 52.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 9, 152–154.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 10, 78–79.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 10–11, 13, 132–133.

- ^ "Around 100 dead in clashes between gold miners in Chad". Africanews. May 30, 2022. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Tubiana 2016.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 102.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Baroin 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Fisher and Fisher 1987, pp. 236–237.

- ^ a b Conklin 2013, search "Le Cœur Italy".

- ^ Jäkel 1977, p. 61.

- ^ Klitzsch 2004, pp. 245, 247.

- ^ Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, pp. 609–610.

- ^ University of Cologne 2015.

- ^ L. 1876, p. 169.

- ^ Thesiger 1939, pp. 434, 438–439.

- ^ "Expeditions supported by the SFAR: Swiss Expedition in Tibesti – Central Sahara". Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Steele 1964, p. 268.

- ^ Steele 1964, pp. 268–270.

- ^ Scott 2017, search "Tibesti" and "'climb Tieroko'".

- ^ Cox 1965, p. 126.

- ^ "Fastest time to climb the highest peaks in all African countries". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Ingram 2001, p. 39.

- ^ Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 78.

- ^ a b Maoundonodji 2009, p. 258.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, p. 32.

- ^ Suayah 2006, p. 564.

- ^ Braun and Passon 2020, p. 144.

- ^ Kaiser 1972, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Chapelle 1982, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Chapelle 1982, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Hughes, Hughes and Bernacsek 1992, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Beauvilain 1996, pp. 21–24.

- ^ a b c d e f Kröpelin 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Nine extraordinary tours" 2019.

- ^ a b Tubiana and Gramizzi 2017, p. 71.

- ^ Grolle 2013.

- ^ Leadbeater 2019.

- ^ "Safety and security – Chad travel advice – GOV.UK". Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Sahelo-Saharan Antelopes Project 2006, p. 11.

- ^ "Lakes of Ounianga". UNESCO. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "Ennedi Massif: Natural and Cultural Landscape". UNESCO. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Davis 1984, p. 8.

- ^ a b Chapelle 1982, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Timbre: Head of sheep and Tibesti". Colnect.com. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Berque 1993, p. 35.

- ^ "Jean Vérame". Encyclopedie Audiovisuelle De L'art Contemporain (in French). Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Ferrari, Tinazzi and D’Erchia 2020, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Buzzati 1984, pp. XI, 27.

- ^ Buzzati 1958, chpt. 39.

Bibliography

- Animals Committee (22nd) (July 7–13, 2006). Document 10.2: Annex 6c: Uromastyx dispar Heyden, 1827. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.490.4004.)

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-8108-7048-2.

- Arsenault, Claire (September 6, 2006). "'La captive du désert' est morte" [The "captive of the desert" is dead] (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-5381-1437-7.

- Baldur, Gabriel (2018). "Exploration of the Tibesti Mountains – Re-appraisal after 50 years". In Runge, Jürgen (ed.). The African Neogene: Climate, Environments and People. International Yearbook of Landscape Evolution and Paleoenvironments. Paleoecology of Africa. Vol. 34: The African Neogene – Climate, Environments and People. ISBN 978-1-1380-6212-2.

- Baroin, Catherine (1985). Anarchie et cohésion sociale chez les Toubou: les Daza Kéšerda (Niger) [Anarchy and social cohesion among the Toubou: Daza Kešerda (Niger)] (in French). ISBN 978-0-521-30476-4.

- Baroin, Catherine (2003). Du sable sec à la montagne humide, deux terrains à l'épreuve d'une même méthodologie [Dry sand to damp mountain, two sites tested with the same methodology] (PDF) (Thesis) (in French). Université de Paris X - Nanterre. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2013.

- Baseline Study C: Etude de l'état des instruments politiques, capacités institutionnelles et niveaux de sensibilisation en relation avec les changements climatiques et les aires protégées en Afrique de l'Ouest: Gambie, Mali, Sierra Leone, Tchad et Togo (PDF) (Report) (in French). United Nations Environment Programme. September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2013.

- Beauvilain, Alain (1996). Pages d'histoire naturelle de la terre tchadienne [The Natural History of the Chadian Land] (PDF) (in French). Centre national d'appui à la recherche. OCLC 54307645. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 8, 2018.

- Beck, Pierre; Huard, Paul (1969). Tibesti, carrefour de la préhistoire saharienne [Tibesti, crossroads of Saharan prehistory] (in French). Arthaud. OCLC 919879871.

- Benda, Peter; Spitzenberger, Friederike; Hanák, Vladimír; Andreas, Michal; Reiter, Anontín; Ševčík, Martin; Šmíd, Jiří; Uhrin, Marcel (2014). "Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Part 11. On the bat fauna of Libya II". Acta Societatis Zoologicae Bohemicae. 78: 1–162.

- JSTOR 29543834.

- Beudels, Marie-Odile (January 30, 2008). "Chad". Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Archived from the originalon November 27, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- .

- Braquehais, Stéphanie (February 14, 2006). "Bardaï, village garnison au cœur du désert" [Bardaï, village garrison in the heart of the desert] (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- Braun, Klaus; Passon, Jacqueline, eds. (2020). Across the Sahara: Tracks, Trade and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Libya. S2CID 177517883.

- OCLC 459008523.

- ISBN 978-0-85635-488-5.

- Camps-fabrer, Henriette (1999). "Guépard" [Cheetah]. .

- Chapelle, Jean (1982) [1957]. Nomades noirs du Sahara : les Toubous [Black nomads of the Sahara: the Toubou] (in French). ISBN 978-2-296-28368-8.

- Collelo, Thomas, ed. (1990). "Chad: Toubou and Daza: Nomads of the Sahara". Chad: A Country Study. LCCN 89600373. Archived from the originalon February 28, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- Conklin, Alice L. (2013). In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850–1950. ISBN 978-0-8014-6903-9.

- Correau, Laurent (August 18, 2008). "1974–1977 L'affaire Claustre et la rupture avec Habré" [1974–1977 The Claustre affair and break with Habré] (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- Cox, A. D. M., ed. (1965). "Expeditions" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 70 (310–311): 120–132. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2020.

- S2CID 144539970.

- JSTOR 41523030.

- El Makkrouf, Ali Ahmed (1988). "Tectonic interpretation of Jabal Eghei area and its regional application to Tibesti orogenic belt, south central Libya (S.P.L.A.J.)". .

- Fearon, James; Laitin, David; Kasara, Kimuli (July 7, 2006). "Chad" (PDF). Stanford University. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2016.

- Ferrari, Massimo; Tinazzi, Claudia; D’Erchia, Annalucia (2020). "New Foundation Cities". In Aste, Niccolò; Della Torre, Stefano; Talamo, Cinzia; Singh Adhikari, Rajendra; S2CID 213102386.

- JSTOR 41409917.

- Geniez, Philippe; Padial, José M.; Crochet, Pierre-André (2011). "Systematics of north African Agama (Reptilia: Agamidae): a new species from the central Saharan mountains". .

- Giazzi, Frank (1996). La Réserve Naturelle Nationale de l'Aïr et du Ténéré (Niger) [The National Nature Reserve of the Aïr and Ténéré (Niger)] (in French). ISBN 978-2-8317-0249-0.

- Ginsberg, Joshua R.; Macdonald, David W. (1990). Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs: An Action Plan for the Conservation of Canids (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2016.

- Gourgaud, Alain; Vincent, Pierre M. (2004). "Petrology of two continental alkaline intraplate series at Emi Koussi volcano, Tibesti, Chad". .

- Grolle, Johann (May 25, 2013). "Miracle in the Sahara: Oasis Sediments Archive Dramatic History". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- JSTOR 1790425.

- Hagedorn, Horst (1997). "Tibesti". In Tillet, Thierry (ed.). Sahara : paléomilieux et peuplement préhistorique au Pléistocène supérieur [Sahara: paleoenvironments and prehistoric populations in the Upper Pleistocene] (in French). OCLC 39372160.

- Hellmich, Walter (1972). Hochgebirgsforschung: Tibesti-Zentrale Sahara arbeiten aus der Hochgebirgsregion [High mountain research: Tibesti-Central-Sahara work from the high mountain region] (in German). Universitätsverlag Wagner. OCLC 174113929.

- Henderson, David H. (April 2, 1984). War since 1945 Seminar: Conflict in Chad, 1975 to Present: A Central African Tragedy (Report). Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Archivedfrom the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Higgins, Rosalyn (July 2, 1993). "The Reactions of Chad to the Libyan Occupation" (PDF). Public sitting held on Friday 2 July 1993, at 10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, President Sir Robert Jennings presiding in the case concerning Territorial Dispute (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Chad). The Hague: International Court of Justice. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 27, 2001.

- Hughes, Ralph H.; Hughes, Jane S.; Bernacsek, Garry M. (1992). "Chad" (PDF). A Directory of African Wetlands (PDF). ISBN 978-2-88032-949-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on September 24, 2012.

- .

- Ingram, Stuart (2001). "Africa: Travel and Adventure" (PDF). Summit. British Mountaineering Council. pp. 37–39. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2020.

- Jacobs, Frank (November 7, 2011). "The World's Largest Sandbox". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Jäkel, Dieter (1977). "The Work of the Field Station at Bardai in the Tibesti Mountains". JSTOR 1796675.

- Kaiser, Karlheinz (1972). "Der känozoische Vulkanismus im Tibesti—Gebirge" [Cenozoic Volcanism in the Tibesti Mountains]. Berliner geographische Abhandlungen (in German). 16: 9–34. .

- Kappen, Josef (1973). "Chapter 10: Response to Extreme Environments". In Ahmadjian, Vernon; Hale, Mason E. (eds.). The Lichens. ISBN 978-0-12-044950-7.

- Klitzsch, Eberhard H. (2004). "From Bardai to SFB 69: The Tibesti Research Station and Later Geoscientific Research in Northeast Africa" (PDF). Die Erde. 135 (3–4): 245–266. ISSN 0013-9998. Archived from the original(PDF) on May 26, 2013.

- Kröpelin, Stefan (July 4, 2017). "UNESCO Sites: An Opportunity for Chad" (Interview). Interviewed by Frederike Müller. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- L., A. (1876). "Voyages du Dr Nachtigall" [Voyages of Dr. Nachtigal]. Le Globe. Revue genevoise de géographie (in French). 15: 167–178. from the original on December 9, 2020.

- Leadbeater, Chris (August 11, 2019). "The most beautiful country in the world that you're not supposed to visit". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- Mahjoub, A. Monem (2015). Uncharted Ethnicities (PDF). Translated by Mathlouthi, Othman. Tanit. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2021.

- Maley, Jean (2000). "Last Glacial Maximum lacustrine and fluviatile Formations in the Tibesti and other Saharan mountains, and large-scale climatic teleconnections linked to the activity of the Subtropical Jet Stream". .

- Maoundonodji, Gilbert (2009). Les enjeux géopolitiques et géostrategiques de l'exploitation du pétrole au Tchad [The geopolitical and geostrategic issues of the exploitation of oil in Chad] (in French). ISBN 978-2-87463-171-9.

- JSTOR 1550163.

- (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2021.

- Mies, Bruno; Lösch, Rainer (1995). "Relative habitat constancy of lichens on the atlantic islands". Cryptogamic Botany. 5: 192–198.

- Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Développement international, direction des Archives (pôle géographique) (December 2016). Tchad [Chad] (Map) (in French). Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021.

- Musch, Tilman (2021). "Exploring Environments through Water: An Ethno-Hydrography of the Tibesti Mountains (Central Sahara)". Ethnobiology Letters. 12 (1): 1–11. S2CID 231814001.

- "Nine extraordinary tours to Africa's unlikeliest destinations". Wanderlust. November 18, 2019. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8139-1628-6.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975). Fage, John D.; Clark, John Desmond; Oliver, Roland Anthony (eds.). The Cambridge History of Africa (PDF). Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 26, 2020.

- Pegram, William J.; Register, Joseph K. Jr.; Fullagar, Paul D.; Ghuma, Mohamed A.; Rogers, John J. W. (1976). "Pan-African ages from a Tibesti Massif batholith, southern Libya". .

- Permenter, Jason L.; S2CID 53463999.

- ASIN B003NHSEK0.

- Ricciardi, Matthew M. (1992). "Title to the Aouzou Strip: A Legal and Historical Analysis". The Yale Journal of International Law. 17 (2): 301–488.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Roos, Christian; Knauf, Sascha; Chuma, Idrissa S.; Maille, Audrey; Callou, Cécile; Sabin, Richard; Portela Miguez, Roberto; Zinner, Dietmar (2021). "New mitogenomic lineages in Papio baboons and their phylogeographic implications". S2CID 227182800.

- Roure, Gil (April 1, 1939). "Le Tibesti, bastion de notre Afrique Noire" [The Tibesti, bastion of our Black Africa] (PDF). L'Illustration (in French). No. 5013. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016.

- Sahelo-Saharan Antelopes Project. Rapport de mission: Prospections des zones prioritaires de conservation pour les Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes au Tchad, et identification de programmes de conservation/développement durable (PDF) (in French). Bonn Convention. Archived from the original(PDF) on May 21, 2013.

- Salam, Mustafa J.; Hammuda, Omar S.; Eliagoubi, Bahlul A. (1991). The Geology of Libya, Volume 5. ISBN 978-0-444-88844-0.

- Salvador, Alfredo (1996). "Amphibians of Northwest Africa". Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service. 109 (109): 1–43. .

- Schultze-Motel, Wolfram (1969). "Eine Moossammlung Aus Dem Tibesti-Gebirge (Nordafrika)" [A Collection of Bryophytes from the Tibesti Mountains (North Africa)]. JSTOR 3995401.

- ISBN 978-1-911342-80-9.

- Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0.

- Sola, M.A.; Worsley, David, eds. (2000). Geological Exploration in Murzuq Basin. ISBN 978-0-08-053246-2.

- Soulié-Märsche, Ingeborg; Bieda, Stephen; Lafond, R.; Maley, Jean; M'Baitoudji, Mathieu; Vincent, Pierre M.; Faure, Hugues (2010). "Charophytes as bio-indicators for lake level high stand at 'Trou au Natron', Tibesti, Chad, during the Late Pleistocene". .

- Steele, Peter R. (1964). "A Note on Tieroko (Tibesti Mountains)" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 69 (308–309): 268–270. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2020.

- Suayah, Ismail B.; Miller, Jonathan S.; Miller, Brent V.; Bayer, Tovah M.; Rogers, John J.W. (2006). "Tectonic significance of Late Neoproterozoic granites from the Tibesti massif in southern Libya inferred from Sr and Nd isotopes and U–Pb zircon data". .

- JSTOR 1787293.

- Thompson, Greg (September 3, 2020). "Stations". National Center for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- Tilho, Jean (1920). Carte provisoire de la région Tibesti. Borkou, Erdi, Ennedi, (mission de l'Institut de France, 1912–1917) [Provisional map of the Tibesti region. Borkou, Erdi, Ennedi, (mission of the Institut de France, 1912–1917)] (Map) (in French). Institut de France.

- Tourte, René (2005). Histoire de la recherche agricole en Afrique tropicale francophone [History of agricultural research in French tropical Africa] (PDF) (in French). Vol. I: Aux sources de l'agriculture africaine: de la Préhistoire au Moyen Âge. ISBN 978-92-5-205407-8. Archived(PDF) from the original on April 20, 2021.

- Tubiana, Jérôme (February 24, 2016). "After Libya, a Rush for Gold and Guns". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- Tubiana, Jérôme; Gramizzi, Claudio (June 2017). Tubu Trouble: State and Statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya Triangle (PDF) (Report). Small Arms Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2020.

- Science Daily. Archivedfrom the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ISBN 978-2-7099-0832-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on August 4, 2019.

- "Zum Weinen" [Makes You Cry]. Der Spiegel (in German). September 15, 1975. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

External links

- The Tibesti Mountains, University of Applied Sciences Burgenland

- Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands, World Wildlife Fund