User:CFCF/sandbox/Stroke

| CFCF/sandbox/Stroke |

|---|

A stroke, sometimes referred to as a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), cerebrovascular insult (CVI), or colloquially brain attack is the loss of

A stroke is a

An ischemic stroke is occasionally treated in a hospital with

Classification

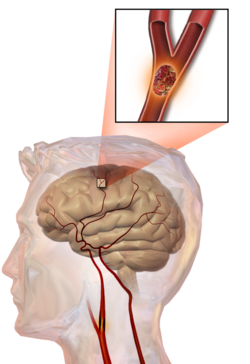

Strokes can be classified into two major categories: ischemic and hemorrhagic.[7] Ischemic strokes are caused by interruption of the blood supply, while hemorrhagic strokes result from the rupture of a blood vessel or an abnormal vascular structure. About 87% of strokes are ischemic, the rest are hemorrhagic. Some hemorrhages develop inside areas of ischemia ("hemorrhagic transformation"). It is unknown how many hemorrhagic strokes actually start as ischemic stroke.[5]

Definition

In the 1970s the World Health Organization defined stroke as a "neurological deficit of cerebrovascular cause that persists beyond 24 hours or is interrupted by death within 24 hours",[8] although the word "stroke" is centuries old. This definition was supposed to reflect the reversibility of tissue damage and was devised for the purpose, with the time frame of 24 hours being chosen arbitrarily. The 24-hour limit divides stroke from transient ischemic attack, which is a related syndrome of stroke symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours.[5] With the availability of treatments which can reduce stroke severity when given early, many now prefer alternative terminology, such as brain attack and acute ischemic cerebrovascular syndrome (modeled after heart attack and acute coronary syndrome, respectively), to reflect the urgency of stroke symptoms and the need to act swiftly.[9]

Ischemic

In an ischemic stroke, blood supply to part of the brain is decreased, leading to dysfunction of the brain tissue in that area. There are four reasons why this might happen:

- Thrombosis (obstruction of a blood vessel by a blood clot forming locally)

- Embolism (obstruction due to an embolus from elsewhere in the body, see below),[5]

- Systemic hypoperfusion (general decrease in blood supply, e.g., in shock)[10]

- Venous thrombosis.[11]

Stroke without an obvious explanation is termed "cryptogenic" (of unknown origin); this constitutes 30-40% of all ischemic strokes.[5][12]

There are various classification systems for acute ischemic stroke. The Oxford Community Stroke Project classification (OCSP, also known as the Bamford or Oxford classification) relies primarily on the initial symptoms; based on the extent of the symptoms, the stroke episode is classified as

Hemorrhagic

Intracranial hemorrhage is the accumulation of blood anywhere within the skull vault. A distinction is made between

Signs and symptoms

Stroke symptoms typically start suddenly, over seconds to minutes, and in most cases do not progress further. The symptoms depend on the area of the brain affected. The more extensive the area of brain affected, the more functions that are likely to be lost. Some forms of stroke can cause additional symptoms. For example, in intracranial hemorrhage, the affected area may compress other structures. Most forms of stroke are not associated with headache, apart from subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral venous thrombosis and occasionally intracerebral hemorrhage.

Early recognition

Various systems have been proposed to increase recognition of stroke. Different findings are able to predict the presence or absence of stroke to different degrees. Sudden-onset face weakness, arm drift (i.e., if a person, when asked to raise both arms, involuntarily lets one arm drift downward) and abnormal speech are the findings most likely to lead to the correct identification of a case of stroke increasing the likelihood by 5.5 when at least one of these is present). Similarly, when all three of these are absent, the likelihood of stroke is significantly decreased (– likelihood ratio of 0.39).[17] While these findings are not perfect for diagnosing stroke, the fact that they can be evaluated relatively rapidly and easily make them very valuable in the acute setting.

Proposed systems include

For people referred to the

Subtypes

If the area of the brain affected contains one of the three prominent

- hemiplegia and muscle weakness of the face

- numbness

- reduction in sensory or vibratory sensation

- initial flaccidity (hypotonicity), replaced by spasticity (hypertonicity), hyperreflexia, and obligatory synergies.[23]

In most cases, the symptoms affect only one side of the body (

In addition to the above CNS pathways, the brainstem gives rise to most of the twelve cranial nerves. A stroke affecting the brain stem and brain therefore can produce symptoms relating to deficits in these cranial nerves:

- altered smell, taste, hearing, or vision (total or partial)

- drooping of eyelid (ptosis) and weakness of ocular muscles

- decreased reflexes: gag, swallow, pupil reactivity to light

- decreased sensation and muscle weakness of the face

- balance problems and nystagmus

- altered breathing and heart rate

- weakness in sternocleidomastoid muscle with inability to turn head to one side

- weakness in tongue (inability to protrude and/or move from side to side)

If the cerebral cortex is involved, the CNS pathways can again be affected, but also can produce the following symptoms:

- typically involved)

- dysarthria (motor speech disorder resulting from neurological injury)

- apraxia (altered voluntary movements)

- visual field defect

- memory deficits (involvement of temporal lobe)

- hemineglect (involvement of parietal lobe)

- disorganized thinking, confusion, hypersexualgestures (with involvement of frontal lobe)

- lack of insight of his or her, usually stroke-related, disability

If the cerebellum is involved, the patient may have the following:

- altered walking gait

- altered movement coordination

- vertigoand or disequilibrium

Associated symptoms

Loss of consciousness, headache, and vomiting usually occurs more often in hemorrhagic stroke than in thrombosis because of the increased intracranial pressure from the leaking blood compressing the brain.

If symptoms are maximal at onset, the cause is more likely to be a subarachnoid hemorrhage or an embolic stroke.

Causes

Thrombotic stroke

In thrombotic stroke a thrombus[24] (blood clot) usually forms around atherosclerotic plaques. Since blockage of the artery is gradual, onset of symptomatic thrombotic strokes is slower. A thrombus itself (even if non-occluding) can lead to an embolic stroke (see below) if the thrombus breaks off, at which point it is called an "embolus." Two types of thrombosis can cause stroke:

- Large vessel disease involves the common and Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, vasculitis), noninflammatory vasculopathy, Moyamoya disease and fibromuscular dysplasia.

- Small vessel disease involves the smaller arteries inside the brain: branches of the lacunar infarcts) and microatheroma (small atherosclerotic plaques).[27]

Embolic stroke

An embolic stroke refers to the blockage of an artery by an arterial embolus, a traveling particle or debris in the arterial bloodstream originating from elsewhere. An embolus is most frequently a thrombus, but it can also be a number of other substances including fat (e.g., from bone marrow in a broken bone), air, cancer cells or clumps of bacteria (usually from infectious endocarditis).[3]

Because an embolus arises from elsewhere, local therapy solves the problem only temporarily. Thus, the source of the embolus must be identified. Because the embolic blockage is sudden in onset, symptoms usually are maximal at start. Also, symptoms may be transient as the embolus is partially resorbed and moves to a different location or dissipates altogether.

Emboli most commonly arise from the heart (especially in atrial fibrillation) but may originate from elsewhere in the arterial tree. In paradoxical embolism, a deep vein thrombosis embolizes through an atrial or ventricular septal defect in the heart into the brain.[3]

Cardiac causes can be distinguished between high and low-risk:[29]

- High risk: atrial fibrillation and coronary artery bypass graft(CABG) surgery.

- Low risk/potential: calcification of the annulus (ring) of the mitral valve, patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal aneurysm, atrial septal aneurysm with patent foramen ovale, left ventricular aneurysm without thrombus, isolated left atrial "smoke" on echocardiography (no mitral stenosis or atrial fibrillation), complex atheroma in the ascending aorta or proximal arch.

Cerebral hypoperfusion

Cerebral hypoperfusion is the reduction of blood flow to all parts of the body. It is most commonly due to

Venous thrombosis

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis leads to stroke due to locally increased venous pressure, which exceeds the pressure generated by the arteries. Infarcts are more likely to undergo hemorrhagic transformation (leaking of blood into the damaged area) than other types of ischemic stroke.[11]

Intracerebral hemorrhage

It generally occurs in small arteries or arterioles and is commonly due to hypertension,

Silent stroke

A

Pathophysiology

Ischemic

Ischemic stroke occurs because of a loss of blood supply to part of the brain, initiating the

As oxygen or glucose becomes depleted in ischemic brain tissue, the production of

Ischemia also induces production of

These processes are the same for any type of ischemic tissue and are referred to collectively as the ischemic cascade. However, brain tissue is especially vulnerable to ischemia since it has little respiratory reserve and is completely dependent on

In addition to injurious effects on brain cells, ischemia and infarction can result in loss of structural integrity of brain tissue and blood vessels, partly through the release of matrix metalloproteases, which are zinc- and calcium-dependent enzymes that break down collagen,

Hemorrhagic

Bleeding within the skull cavity can occur from various causes.

Diagnosis

Stroke is diagnosed through several techniques: a neurological examination (such as the

Physical examination

A

Imaging

For diagnosing ischemic stroke in the emergency setting:[42]

- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 16%

- specificity= 96%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 83%

- specificity= 98%

For diagnosing hemorrhagic stroke in the emergency setting:

- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 89%

- specificity= 100%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 81%

- specificity= 100%

For detecting chronic hemorrhages, MRI scan is more sensitive.[43]

For the assessment of stable stroke, nuclear medicine scans SPECT and PET/CT may be helpful. SPECT documents cerebral blood flow and PET with FDG isotope the metabolic activity of the neurons.

Underlying cause

When a stroke has been diagnosed, various other studies may be performed to determine the underlying cause. With the current treatment and diagnosis options available, it is of particular importance to determine whether there is a peripheral source of emboli. Test selection may vary, since the cause of stroke varies with age, comorbidity and the clinical presentation. Commonly used techniques include:

- an carotid stenosis) or dissection of the precerebral arteries;

- an arrhythmiasand resultant clots in the heart which may spread to the brain vessels through the bloodstream);

- a Holter monitor study to identify intermittent arrhythmias;

- an angiogram of the cerebral vasculature (if a bleed is thought to have originated from an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation);

- blood tests to determine hypercholesterolemia, homocysteinuria.

Prevention

Given the disease burden of strokes,

Risk factors

The most important modifiable risk factors for stroke are high blood pressure and atrial fibrillation (although magnitude of this effect is small: the evidence from the Medical Research Council trials is that 833 patients have to be treated for 1 year to prevent one stroke

No high-quality studies have shown the effectiveness of interventions aimed at weight reduction, promotion of regular exercise, reducing alcohol consumption or smoking cessation.[59] Nonetheless, given the large body of circumstantial evidence, best medical management for stroke includes advice on diet, exercise, smoking and alcohol use.[60] Medication or drug therapy is the most common method of stroke prevention; carotid endarterectomy can be a useful surgical method of preventing stroke.

Blood pressure

Atrial fibrillation

Those with atrial fibrillation have a 5% a year risk of stroke, and this risk is higher in those with valvular atrial fibrillation.[71] Depending on the stroke risk, anticoagulation with medications such as warfarin or aspirin is useful for prevention.[72]

Blood lipids

High cholesterol levels have been inconsistently associated with (ischemic) stroke.

Diabetes mellitus

Anticoagulation drugs

Oral anticoagulants such as

In primary prevention however, antiplatelet drugs did not reduce the risk of ischemic stroke while increasing the risk of major bleeding.[82][83] Further studies are needed to investigate a possible protective effect of aspirin against ischemic stroke in women.[84][85]

Surgery

Carotid endarterectomy or carotid angioplasty can be used to remove atherosclerotic narrowing (stenosis) of the carotid artery. There is evidence supporting this procedure in selected cases.[60] Endarterectomy for a significant stenosis has been shown to be useful in the prevention of further strokes in those who have already had one.[86] Carotid artery stenting has not been shown to be equally useful.[87][88] Patients are selected for surgery based on age, gender, degree of stenosis, time since symptoms and patients' preferences.[60] Surgery is most efficient when not delayed too long —the risk of recurrent stroke in a patient who has a 50% or greater stenosis is up to 20% after 5 years, but endarterectomy reduces this risk to around 5%. The number of procedures needed to cure one patient was 5 for early surgery (within two weeks after the initial stroke), but 125 if delayed longer than 12 weeks.[89][90]

Screening for carotid artery narrowing has not been shown to be a useful screening test in the general population.[91] Studies of surgical intervention for carotid artery stenosis without symptoms have shown only a small decrease in the risk of stroke.[92][93] To be beneficial, the complication rate of the surgery should be kept below 4%. Even then, for 100 surgeries, 5 patients will benefit by avoiding stroke, 3 will develop stroke despite surgery, 3 will develop stroke or die due to the surgery itself, and 89 will remain stroke-free but would also have done so without intervention.[60]

Diet

Nutrition, specifically the

Women

A number of specific recommendations have been made for women including: taking aspirin after the 11th week of pregnancy if there is a history of previous chronic high blood pressure, blood pressure medications in pregnancy if the blood pressure is greater than 150 mmHg systolic or greater than 100 mmHg diastolic. In those who have previously had

Previous stroke or TIA

Keeping blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg is recommended.

Anticoagulants, when used following stroke, should not be stopped for dental procedures.[101]

If studies show carotid stenosis, and the person has residual function in the affected side, carotid endarterectomy (surgical removal of the stenosis) may decrease the risk of recurrence if performed rapidly after stroke.

Management

Ischemic stroke

Definitive therapy is aimed at removing the blockage by breaking the clot down (thrombolysis), or by removing it mechanically (thrombectomy). The philosophical premise underlying the importance of rapid stroke intervention was crystallized as Time is Brain! in the early 1990s.[102] Years later, that same idea, that rapid cerebral blood flow restoration results in fewer brain cells dying, has been proved and quantified.[103]

Tight control of blood sugars in the first few hours does not improve outcomes and may cause harm.[104] High blood pressure is also not typically lowered as this has not been found to be helpful.

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis with

Its use is endorsed by the

Hemicraniectomy

Large territory strokes can cause significant edema of the brain with secondary brain injury in surrounding tissue. This phenomenon is mainly encountered in strokes of the middle cerebral artery territory, and is also called "malignant cerebral infarction" because it carries a dismal prognosis. Relief of the pressure may be attempted with medication, but some require

Hemorrhagic stroke

People with intracerebral hemorrhage require neurosurgical evaluation to detect and treat the cause of the bleeding, although many may not need surgery. Anticoagulants and antithrombotics, key in treating ischemic stroke, can make bleeding worse. People are monitored for changes in the level of consciousness, and their blood pressure, blood sugar, and oxygenation are kept at optimum levels.[citation needed]

Stroke unit

Ideally, people who have had a stroke are admitted to a "stroke unit", a ward or dedicated area in hospital staffed by nurses and therapists with experience in stroke treatment. It has been shown that people admitted to a stroke unit have a higher chance of surviving than those admitted elsewhere in hospital, even if they are being cared for by doctors without experience in stroke.[5][113]

When an acute stroke is suspected by history and physical examination, the goal of early assessment is to determine the cause. Treatment varies according to the underlying cause of the stroke, thromboembolic (ischemic) or hemorrhagic.

Rehabilitation

A rehabilitation team is usually multidisciplinary as it involves staff with different skills working together to help the patient. These include physicians trained in rehabilitation medicine,

Good

For most people with stroke,

Patients may have particular problems, such as

Treatment of spasticity related to stroke often involves early mobilizations, commonly performed by a physiotherapist, combined with elongation of spastic muscles and sustained stretching through various positionings.[23] Gaining initial improvement in range of motion is often achieved through rhythmic rotational patterns associated with the affected limb.[23] After full range has been achieved by the therapist, the limb should be positioned in the lengthened positions to prevent against further contractures, skin breakdown, and disuse of the limb with the use of splints or other tools to stabilize the joint.[23] Cold in the form of ice wraps or ice packs have been proven to briefly reduce spasticity by temporarily dampening neural firing rates.[23] Electrical stimulation to the antagonist muscles or vibrations has also been used with some success.[23]

Some current and future therapy methods include the use of virtual reality and video games for rehabilitation. These forms of rehabilitation offer potential for motivating patients to perform specific therapy tasks that many other forms do not.[119] Many clinics and hospitals are adopting the use of these off-the-shelf devices for exercise, social interaction and rehabilitation because they are affordable, accessible and can be used within the clinic and home.[119]

Other novel non-invasive rehabilitation methods are currently being developed to augment physical therapy to improve motor function of stroke patients, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS)[120] and robotic therapies.[121]

A stroke can also reduce people's general fitness.[122] Reduced fitness can reduce capacity for rehabilitation as well as general health.[123] A systematic review found that there are inadequate long-term data about the effects of exercise and training on death, dependence and disability after a stroke.[122] However, cardiorespiratory training added to walking programs in rehabilitation can improve speed, tolerance and independence during walking.[122]

Prognosis

Disability affects 75% of stroke survivors enough to decrease their employability.[124] Stroke can affect peoples physically, mentally, emotionally, or a combination of the three. The results of stroke vary widely depending on size and location of the lesion.[125] Dysfunctions correspond to areas in the brain that have been damaged.

Some of the physical disabilities that can result from stroke include muscle weakness, numbness,

Emotional problems resulting from stroke can result from direct damage to emotional centers in the brain or from frustration and difficulty adapting to new limitations. Post-stroke emotional difficulties include

.30 to 50% of stroke survivors suffer post stroke depression, which is characterized by lethargy, irritability, sleep disturbances, lowered self esteem, and withdrawal.[126]

Emotional lability, another consequence of stroke, causes the patient to switch quickly between emotional highs and lows and to express emotions inappropriately, for instance with an excess of laughing or crying with little or no provocation. While these expressions of emotion usually correspond to the patient's actual emotions, a more severe form of emotional lability causes patients to laugh and cry pathologically, without regard to context or emotion.[124] Some patients show the opposite of what they feel, for example crying when they are happy.[127] Emotional lability occurs in about 20% of stroke patients.

Cognitive deficits resulting from stroke include perceptual disorders, Aphasia,[128] dementia,[129] and problems with attention[130] and memory.[131] A stroke sufferer may be unaware of his or her own disabilities, a condition called anosognosia. In a condition called hemispatial neglect, a patient is unable to attend to anything on the side of space opposite to the damaged hemisphere.

Cognitive and psychological outcome after a stroke can be affected by the age at which the stroke happened, pre-stroke baseline intellectual functioning, psychiatric history and whether there is pre-existing brain pathology.[132]

Up to 10% of people following a stroke develop seizures, most commonly in the week subsequent to the event; the severity of the stroke increases the likelihood of a seizure.[133][134]

Epidemiology

| no data <250 250-425 425-600 600-775 775-950 950-1125 | 1125-1300 1300-1475 1475-1650 1650-1825 1825-2000 >2000 |

Stroke was the second most frequent cause of death worldwide in 2011, accounting for 6.2 million deaths (~11% of the total). [136] Approximately 17 million people had a stroke in 2010 and 33 million people have previously had a stroke and were still alive.[137] Between 1990 and 2010 the number of strokes decrease by approximately 10% in the developed world and increased by 10% in the developing world.[137] Overall two thirds of strokes occurred in those over 65 years old.[137]

It is ranked after heart disease and before cancer.

The incidence of stroke increases exponentially from 30 years of age, and etiology varies by age.[139] Advanced age is one of the most significant stroke risk factors. 95% of strokes occur in people age 45 and older, and two-thirds of strokes occur in those over the age of 65.[126][28] A person's risk of dying if he or she does have a stroke also increases with age. However, stroke can occur at any age, including in childhood.

Family members may have a genetic tendency for stroke or share a lifestyle that contributes to stroke. Higher levels of Von Willebrand factor are more common amongst people who have had ischemic stroke for the first time.[140] The results of this study found that the only significant genetic factor was the person's blood type. Having had a stroke in the past greatly increases one's risk of future strokes.

Men are 25% more likely to suffer strokes than women,

History

Episodes of stroke and familial stroke have been reported from the 2nd millennium BC onward in ancient Mesopotamia and Persia.[141] Hippocrates (460 to 370 BC) was first to describe the phenomenon of sudden paralysis that is often associated with ischemia. Apoplexy, from the Greek word meaning "struck down with violence," first appeared in Hippocratic writings to describe this phenomenon.[142][143] The word stroke was used as a synonym for apoplectic seizure as early as 1599,[144] and is a fairly literal translation of the Greek term.

In 1658, in his Apoplexia,

Wepfer also identified the mainThe term cerebrovascular accident was introduced in 1927, reflecting a "growing awareness and acceptance of vascular theories and (...) recognition of the consequences of a sudden disruption in the vascular supply of the brain".[146] Its use is now discouraged by a number of neurology textbooks, reasoning that the connotation of fortuitousness carried by the word accident insufficiently highlights the modifiability of the underlying risk factors.[147][148][149] Cerebrovascular insult may be used interchangeably.[150]

The term brain attack was introduced for use to underline the acute nature of stroke according to the

Research

Angioplasty and stenting

Angioplasty and stenting have begun to be looked at as possible viable options in treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Intra-cranial stenting in symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis, the rate of technical success (reduction to stenosis of <50%) ranged from 90-98%, and the rate of major peri-procedural complications ranged from 4-10%. The rates of restenosis and/or stroke following the treatment were also favorable. This data suggests that a randomized controlled trial is needed to more completely evaluate the possible therapeutic advantage of this preventative measure.[153]

Mechanical thrombectomy

Removal of the clot may be attempted in those where it occurs within a large blood vessel and may be an option for those who either are not eligible for or do not improve with intravenous thrombolytics.[154] Significant complications occur in about 7%.[155] As of October 2013[update], trials have not shown positive results.[156]

Neuroprotection

Drugs that scavenge

References

- PMID 19751827.

- ^ ISBN 978-0071748896.).

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) Cite error: The named reference "Harrison's" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page - ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5. Cite error: The named reference "Robbins" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- PMID 16282541.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 18468545.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19776034.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Brain Basics: Preventing Stroke". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 2009-10-24.

- OCLC 4757533.

- PMID 14605325.

- PMID 1878825.

- ^ PMID 15858188.

- PMID 18208534.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 1675378.. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Later publications distinguish between "syndrome" and "infarct", based on evidence from imaging. "Syndrome" may be replaced by "hemorrhage" if imaging demonstrates a bleed. See Internet Stroke Center. "Oxford Stroke Scale" - PMID 11070389.

- ^ Osterweil, Neil. "Methamphetamine induced ischemic strokes". Medpagetoday. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- PMID 7678184.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15900010.

- PMID 10371574.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9799012.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10092713.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 68: Stroke. London, 2008.

- PMID 16239179.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f O'Sullivan, Susan.B (2007). "Stroke". Physical Rehabilitation. Vol. 5. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. p. 719.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "OSul07_719" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Thrombus". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Circle of Willis". The Internet Stroke Center.

- ^ "Brain anaurysm - Introduction". NHS Choices.

- PMID 5708546.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (1999). "Stroke: Hope Through Research". National Institutes of Health.

- PMID 16240340.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Hypertension".

- PMID 20453400.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 1519274.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12865617.

- PMID 11779883.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20074922.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-963-226-293-2.

- ^ Brunner and Suddarth's Textbook on Medical-Surgical Nursing, 11th Edition

- ISBN 978-0071748896.)

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help - ISBN 978-0071748896.)

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help - ^ PMID 20713126.

- PMID 16244286.

- PMID 17258669.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15494579.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 12234233.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16675728.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Use of Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Heart Attack and Stroke". FDA. 05/02/2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c NPS Prescribing Practice Review 44: Antiplatelets and anticoagulants in stroke prevention (2009). Available at nps.org.au

- ^ PMID 11786451.

- PMID 2861880.

- PMID 19675081.

- PMID 10501270.

- PMID 7596004.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12578491.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 1891081.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21653800.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Stroke Risk Factors". American Heart Association. 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- PMID 3810763.

- PMID 17404126.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 14705756.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 16920313.

- PMID 8614485.

- PMID 19454737.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12759325.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 8551820.

- PMID 9412649.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10459960.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10752701.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 18378519.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11130523.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12479763.

- PMID 3632164.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16908781.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 2619783.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 18187070.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 7802520.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9742976.

- PMID 16214598.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10371234.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 10796426.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16714187.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17239798.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10714657.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16950176.

- PMID 16418466.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17949479.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 12531577.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 18241759.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17943745.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15043958.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16087900.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 18087056.

- PMID 15135594.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16235289.

- PMID 16873712.

- PMID 21980387.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 20937919.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 24503673.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 24788967.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17577005.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 23713086.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Gomez CR: Time is Brain! J Stroke and Cerebrovasc Dis 3:1-2. 1993, additional Time

- PMID 16339467.

- PMID 21901697.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 22632907.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 22996959.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 7477192.

- PMID 19821269.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16769953.

- ^ "Position Statement on the Use of Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy in the Treatment of Stroke". American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- PMID 20360549.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21190097.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 24026639.

- ^ http://www.stroke.scot.nhs.uk/docs/UseOfAnkle-FootOrthosesFollowingStroke.pdf

- ^ O'Sullivan 2007, pp. 471, 484, 737, 740

- PMID 21480809.

- PMID 16235357.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20464716.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ .

- PMID 17611487.

- PMID 20852421.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 22071806.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). "After a stroke: Does fitness training improve overall health and mobility?". Informed Health Online. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ a b Coffey C. Edward, Cummings Jeffrey L, Starkstein Sergio, Robinson Robert (2000). Stroke - the American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Geriatric Neuropsychiatry (Second ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press. pp. 601–617.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stanford Hospital & Clinics. "Cardiovascular Diseases: Effects of Stroke". Retrieved 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ OCLC 40856888 42835161.)

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ )

- PMID 21459427.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16239182.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17102702.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19666037.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9259753.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9437276.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". WHO.

- ^ PMID 24449944.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21778445.

- )

- PMID 16990571.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20185778.

- ^ PMID 8711815.

- ^ Kopito, Jeff (September 2001). "A Stroke in Time". MERGINET.com. 6 (9). [dead link]

- ^ R. Barnhart, ed. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology (1995)

- PMID 4914683.

- ISBN 978-0-444-52009-8. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-340-99070-4. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-6947-1. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-4004-8. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ a b Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. Elsevier. 2009.

- ^ "What is a Stroke/Brain Attack?" (PDF). National Stroke Association. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ Segen's Medical Dictionary. Farlex, Inc. 2010.

- PMID 17826637.

- PMID 22182267.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Ortega-Lopez Y, Llanos-Mendez A (2010). "[Mechanical thrombectomy with MERCI device. Ischaemic stroke]". Andalusian Agency for Health Technology Assessment.

- PMID 24155740.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - PMID 16467546.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16946150.

Further reading

- J. P. Mohr, Dennis Choi, James Grotta, Philip Wolf (2004). Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone. OCLC 50477349 52990861.)

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Charles P. Warlow, Jan van Gijn, Martin S. Dennis, Joanna M. Wardlaw, John M. Bamford, Graeme J. Hankey, Peter A. G. Sandercock, Gabriel Rinkel, Peter Langhorne, Cathie Sudlow, Peter Rothwell (2008). Stroke: Practical Management (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2766-0.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link