Barrett's esophagus

| Barrett's esophagus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Barrett's oesophagus, Allison-Johnstone anomaly, columnar epithelium lined lower oesophagus (CELLO) |

| |

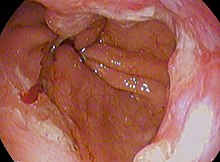

| Endoscopic image of Barrett's esophagus, which is the area of dark reddish-brown mucosa at the base of the esophagus. (Biopsies showed intestinal metaplasia.) | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology General surgery |

| Symptoms | Nausea |

Barrett's esophagus is a condition in which there is an abnormal (

The main cause of Barrett's esophagus is thought to be an adaptation to chronic acid exposure from reflux esophagitis.

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased substantially in the Western world in recent years.[1] The condition is found in 5–15% of patients who seek medical care for heartburn (gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD), although a large subgroup of patients with Barrett's esophagus are asymptomatic. The condition is named after surgeon Norman Barrett (1903–1979) even though the condition was originally described by Philip Rowland Allison in 1946.[5][6][7]

Signs and symptoms

The change from normal to premalignant cells indicate Barrett's esophagus does not cause any particular symptoms. Barrett's esophagus, however, is associated with these symptoms:

- frequent and longstanding heartburn

- trouble swallowing (dysphagia)

- vomiting blood (hematemesis)

- pain under the sternum where the esophagus meets the stomach

- pain when swallowing (odynophagia), which can lead to unintentional weight loss

The risk of developing Barrett's esophagus is increased by central obesity (vs. peripheral obesity).[8] The exact mechanism is unclear. The difference in distribution of fat among men (more central) and women (more peripheral) may explain the increased risk in males.[9]

Pathophysiology

Barrett's esophagus occurs due to chronic inflammation. The principal cause of chronic inflammation is gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD (UK: GORD). In this disease, acidic stomach, bile, and small intestine and pancreatic contents cause damage to the cells of the lower esophagus. In turn, this provokes an advantage for cells more resistant to these noxious stimuli in particular HOXA13-expressing stem cells that are characterised by distal (intestinal) characteristics and outcompete the normal squamous cells.[10]

This mechanism also explains the selection of

Researchers are unable to predict who with heartburn will develop Barrett's esophagus. While no relationship exists between the severity of heartburn and the development of Barrett's esophagus, a relationship does exist between chronic heartburn and the development of Barrett's esophagus. Sometimes, people with Barrett's esophagus have no heartburn symptoms at all.

Some anecdotal evidence indicates those with the eating disorder

During episodes of reflux, bile acids enter the esophagus, and this may be an important factor in carcinogenesis.[13] Individuals with GERD and BE are exposed to high concentrations of deoxycholic acid that has cytotoxic effects and can cause DNA damage.[13][14]

Diagnosis

Both macroscopic (from endoscopy) and microscopic positive findings are required to make a diagnosis. Barrett's esophagus is marked by the presence of

Screening

Screening endoscopy is recommended among males over the age of 60 who have reflux symptoms that are of long duration and not controllable with treatment.[16] Among those not expected to live more than five years screening is not recommended.[16]

The Seattle protocol is used commonly in endoscopy to obtain endoscopic biopsies for screening, taken every 1 to 2 cm from the gastroesophageal junction.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic In Scotland, the local NHS started using a swallowable sponge (Cytosponge) in hospitals to collect cell samples for diagnosis.[17] Preliminary studies have shown this diagnostic test to be a useful tool for screening people with heartburn symptoms and improved diagnosis.[18][19]

Intestinal metaplasia

The presence of goblet cells, called intestinal metaplasia, is necessary to make a diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus. This frequently occurs in the presence of other metaplastic columnar cells, but only the presence of goblet cells is diagnostic. The metaplasia is grossly visible through a

Many histologic mimics of Barrett's esophagus are known (i.e. goblet cells occurring in the transitional epithelium of normal esophageal submucosal gland ducts, "pseudogoblet cells" in which abundant foveolar [gastric] type mucin simulates the acid mucin true goblet cells). Assessment of relationship to submucosal glands and transitional-type epithelium with examination of multiple levels through the tissue may allow the pathologist to reliably distinguish between goblet cells of submucosal gland ducts and true Barrett's esophagus (specialized columnar metaplasia). The histochemical stain Alcian blue pH 2.5 is also frequently used to distinguish true intestinal-type mucins from their histologic mimics. Recently, immunohistochemical analysis with antibodies to CDX-2 (specific for mid and hindgut intestinal derivation) has also been used to identify true intestinal-type metaplastic cells. The protein AGR2 is elevated in Barrett's esophagus[21] and can be used as a biomarker for distinguishing Barrett epithelium from normal esophageal epithelium.[22]

The presence of intestinal metaplasia in Barrett's esophagus represents a marker for the progression of metaplasia towards dysplasia and eventually adenocarcinoma. This factor combined with two different immunohistochemical expression of p53, Her2 and p16 leads to two different genetic pathways that likely progress to dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus.[23] Also intestinal metaplastic cells can be positive for CK 7+/CK20-.[24]

Epithelial dysplasia

After the initial diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus is rendered, affected persons undergo annual surveillance to detect changes that indicate higher risk to progression to cancer: development of epithelial dysplasia (or "intraepithelial neoplasia").[25] Among all metaplastic lesions, around 8% were associated with dysplasia. particularly a recent study demonstrated that dysplastic lesions were located mainly in the posterior wall of the esophagus.[26]

Considerable variability is seen in assessment for dysplasia among pathologists. Recently, gastroenterology and GI pathology societies have recommended that any diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett be confirmed by at least two fellowship-trained GI pathologists prior to definitive treatment for patients.[15] For more accuracy and reproducibility, it is also recommended to follow international classification systems, such as the "Vienna classification" of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia (2000).[27]

Management

Many people with Barrett's esophagus do not have dysplasia. Medical societies recommend that if a patient has Barrett's esophagus, and if the past two endoscopy and biopsy examinations have confirmed the absence of dysplasia, then the patient should not have another endoscopy within three years.[28][29][30]

Endoscopic surveillance of people with Barrett's esophagus is often recommended, although little direct evidence supports this practice.[1] Treatment options for high-grade dysplasia include surgical removal of the esophagus (esophagectomy) or endoscopic treatments such as endoscopic mucosal resection or ablation (destruction).[1]

The risk of malignancy is highest in the United States in Caucasian men over fifty years of age with more than five years of symptoms. Current recommendations include routine

Anti-reflux surgery has not been proven to prevent esophageal cancer. However, the indication is that

There is presently no reliable way to determine which patients with Barrett's esophagus will go on to develop esophageal cancer, although a recent study found the detection of three different genetic abnormalities was associated with as much as a 79% chance of developing cancer in six years.[36]

Endoscopic mucosal resection has also been evaluated as a management technique.[37] Additionally an operation known as a Nissen fundoplication can reduce the reflux of acid from the stomach into the esophagus.[38]

In a variety of studies, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (

Prognosis

adenocarcinoma (poor; signet-ringcell)

Barrett's esophagus is a pre-malignant condition, not a cancerous one.

A small subset of patients with Barrett's esophagus will eventually develop malignant

The risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma increases based on how severe the Barrett's esophagus has become.[44] Longer length of the Barrett's esophagus region is also associated with increased risk of developing cancer.[44][45]

Progression and severity of Barrett's esophagus is measured by amount of dysplasia the cells show. Dysplasia is scored on a five-tier system: [45]

- negative for dysplasia (non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus or NDBE)

- indefinite for dysplasia (IND)

- low-grade dysplasia (LGD)

- high-grade dysplasia (HGD)

- carcinoma

A 2016 study found that the rate of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus patients with no dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia, and high-grade dysplasia are around 0.6%, 13.4%, and 25%, respectively.[46]

However, for low-grade dysplasia, the true yearly rate of progression to cancer remains difficult to estimate, as results are highly variable from study to study, from 13.4% down to 0.84%.[44] This is partly due to each study having a different mix of intermediate disease states being combined under the umbrella diagnosis of LGD.[45]

Epidemiology

The incidence in the United States among Caucasian men is eight times the rate among Caucasian women and five times greater than African American men. Overall, the male to female ratio of Barrett's esophagus is 10:1.[47] Several studies have estimated the prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population to be 1.3% to 1.6% in two European populations (Italian[48] and Swedish[49]), and 3.6% in a Korean population.[50]

History

The condition is named after Australian

A further association was made with adenocarcinoma in 1975.[54]

References

- ^ S2CID 13141959.

- S2CID 42893278.

- S2CID 6715044.

- S2CID 2274838.

- PMID 18904843.

- ^ S2CID 21531132.

- ISBN 9780128025116.

- PMID 17681161.

- PMID 20094044.

- PMID 34099670.

- PMID 8905379. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Bulimia and cancer - what you need to know - Bulimia Help". Bulimiahelp.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ S2CID 1099567.

- PMID 15652226.

- ^ PMID 15711008.

- ^ PMID 25869390.

- ^ "Cytosponge". www.nhsinform.scot. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- S2CID 242399505.

- PMID 32738955.

- ^ "Barrett's Esophagus". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- PMID 14967811.

- PMID 17994709.

- PMID 26614646.

- PMID 22591041.

- PMID 17021130.

- PMID 27436487.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 10896917.

- ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, archived from the original(PDF) on August 9, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- PMID 21376940.

- S2CID 8443847.

- ^ S2CID 24224546.

- ^ PMID 19474425.

- ^ PMID 21679712.

- ^ S2CID 38316532.

- PMID 17643436.

- PMID 17326708.

- S2CID 12959801.

- PMID 14759403.

- PMID 12512029.

- PMID 16321762.

- PMID 32329063.

- ^ Schieszer, John (29 September 2019). "Study Shows Association Between Low-Dose Aspirin Use and Risk for Gastric and Esophageal Cancers". Oncology Nurse Advisor.

- PMID 17185192.

- ^ PMID 38001670.

- ^ PMID 36673131.

- PMID 27441494.

- .

- S2CID 206947077.

- PMID 16344051.

- S2CID 46543142.

- S2CID 72315839.

- PMID 10714623.

- ^ PMID 13077502.

- PMID 1186274.