Cat gap

The cat gap is a period in the

Cat evolution

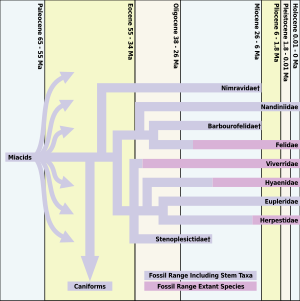

All modern carnivorans, including cats, evolved from miacoids, which existed from approximately 66 to 33 million years ago. There were other earlier cat-like species but Proailurus (meaning "before the cat"; also called "Leman's Dawn Cat"), which appeared about 30 million years ago, is generally considered the first "true cat".[2]

Following the appearance of the dawn cat, there is little in the fossil record for 10 million years to suggest that cats would prosper. In fact, although Proailurus persisted for at least 14 million years, there are so few felid fossils towards the end of the dawn cat's reign that paleontologists refer to this as the "cat gap". The turning point for cats came about with the appearance of a new genus of felids, Pseudaelurus.[2]

The increase in disparity through the early Miocene occurs during a time when few feliform fossils have been found in North America. The hypercarnivorous nimravid feliforms were extinct in North America after 26

Nimravids and barbourofelids were

Possible causes

Hypercarnivorous tendency

The history of carnivorous mammals is characterized by a series of rise-and-fall patterns of diversification, in which declining

The

Changes in climate and habitat

Another possible explanation for the extinction of feliforms in North America is

Why did these cat-like creatures die out in North America (while surviving in Eurasia) with no replacement by the true cats? Their fate may be owed to the same factors that created the diversity of herbivorous mammals, for most cats need forest or cover from which to hunt. In an increasingly open America the nimravids may have found themselves without an ecological perch to hunt from, particularly if the competition with dogs prevented them from colonising the savannas.[5]

Other

Volcanic activity has also been promoted as a possible cause of the cat gap as well as other extinctions during this time period. The

Another possible cause of the cat gap could have been the

There is also evidence that during the Miocene a sill surrounding the Arctic Ocean, known as the Greenland–Scotland Ridge, subsided, allowing more cold polar water to escape into the North Atlantic. As the salinity of the North Atlantic grew and as outflow of cold polar water increased, so the thermohaline circulation increased in vigour, providing the mild winter temperatures and large amounts of moisture to the North Atlantic, which are prerequisites to the build-up of the large continental ice caps on the adjacent cold continents.[6]

Evolution of caniforms during the gap

It has been suggested by some that as a result of the cat gap caniforms (dog-like species including canids, bears, weasels, and other related taxa) evolved to fill more carnivorous and hypercarnivorous ecological niches that would otherwise have been filled by cats.[7] This conclusion, however, is disputed.[8]

During or just prior to this "cat gap", numerous caniform species evolve catlike features indicative of hypercarnivory, such as reduced snouts, somewhat enlarged canines, and fairly extreme reduction of their crushing

However, other paleontologists take issue with this conclusion:

It has been suggested that canids evolved hypercarnivorous morphologies because feliforms were absent during this period (the "cat-gap", 26–16 Ma). The data presented here do not support this hypothesis. In the calculated

creodonts are found. More pertinent to the issue at hand, however, is that most of these hypercarnivorous canids were present before the disappearance of the nimravids, and all became extinct before the appearance of felids ... There was a progressive and marked decrease in hypercarnivorous forms during the "cat-gap". 28–20 Ma are characterized by above average extinction intensities and below average origination intensities. 20 Ma was marked by an increase in origination intensity, and 18 Ma showed a decrease in extinction intensity and a large increase in origination intensity. Nonetheless, despite increased origination intensities and decreased extinction intensities near the end of the "cat-gap" (20–16 Ma), there was still no substantial invasion of hypercarnivorous morphospace until the immigration of felids into North America.[8]

References

- S2CID 21117744. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-8482-5.

- S2CID 85608067. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.09.027. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ISBN 0-8021-3888-8.

- ^ Haggart, B. A. (2000). "Ice-age Theories". The Oxford Companion to the Earth. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 10989917. Retrieved 2008-11-28.