Geology of Scotland

The geology of Scotland is unusually varied for a country of its size, with a large number of different

The existing

Scotland has also had a role to play in many significant discoveries such as plate tectonics and the development of theories about the formation of rocks and was the home of important figures in the development of the science including James Hutton (the "father of modern geology"),[2] Hugh Miller and Archibald Geikie.[3] Various locations such as 'Hutton's Unconformity' at Siccar Point in Berwickshire and the Moine Thrust in the northwest were also important in the development of geological science.

Overview

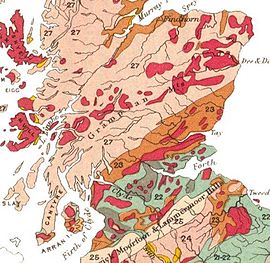

From a geological and geomorphological perspective the country has three main sub-divisions all of which were affected by Pleistocene glaciations.

Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands lie to the north and west of the

.

The Hebridean archipelago outlier of

The geology of Shetland is complex with numerous

Midland Valley

Often referred to as the

Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands are a range of hills almost 200 km (120 mi) long, interspersed with broad valleys. They lie south of a second fault line running from Ballantrae towards Dunbar.[10] The geological foundations largely comprise Silurian deposits laid down some 4-500 million years ago.[11][12]

Post-glacial events

The whole of Scotland was covered by ice sheets during the

Chronology

Archean and Proterozoic eons

The oldest rocks of Scotland are the

Torridonian sandstones were also laid down in this period over the gneisses, and these contain the oldest signs of life in Scotland. In later Precambrian times, thick sediments of sandstones, limestones muds and lavas were deposited in what is now the Highlands of Scotland.[21][22]

Palaeozoic era

Cambrian period

Further

Ordovician period

The proto-Scotland landmass moved northwards, and from 460 to 430 Ma,

Silurian period

During the Silurian period (444–419 Ma) the continent of Laurentia gradually collided with Baltica, joining Scotland to the area that would become England and Europe. Sea levels rose as the Ordovician ice sheets melted, and tectonic movements created major faults which assembled the outline of Scotland from previously scattered fragments. These faults are the Highland Boundary Fault, separating the Lowlands from the Highlands, the Great Glen Fault that divides the North-west Highlands from the Grampians, the Southern Uplands Fault and the Iapetus Suture, which runs from the Solway Firth to Lindisfarne and which marks the close of the Iapetus Ocean and the joining of northern and southern Britain.[21][26][27]

Silurian rocks form the

Devonian period

The Scottish landmass now formed part of the

Elsewhere volcanic activity, possibly as a result of the closing of the Iapetus Suture, created the

Carboniferous period

During the

Permian period

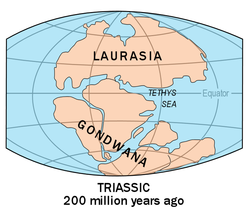

The Old Red Sandstone Continent became a part of the supercontinent

At the close of this period came the Permian–Triassic extinction event in which 96% of all marine species vanished[35] and from which biodiversity took 30 million years to recover.

Mesozoic era

Triassic period

During the Triassic (252–201 Ma), much of Scotland remained in desert conditions, with higher ground in the Highlands and Southern Uplands providing sediment to the surrounding basins via flash floods. This is the origin of sandstone outcrops near Dumfries, Elgin and the Isle of Arran. Towards the close of this period sea levels began to rise and climatic conditions became less arid.[36]

Jurassic period

As the

Cretaceous period

In the

Cenozoic era

Palaeogene period

In the early

Neogene period

Miocene and Pliocene epochs

In the Miocene and Pliocene epochs further uplift and erosion occurred in the Highlands. Plant and animal types developed into their modern forms. Scotland lay in its present position on the globe. As the Miocene progressed, temperatures dropped and remained similar to today's.[44][46]

Quaternary period

Pleistocene epoch

Several

Holocene epoch

Over the last twelve thousand years the most significant new geological features have been the deposits of

a low lying dune pasture land formed as the sea level dropped leaving a raised beach. In the present day, Scotland continues to move slowly north.Geologists in Scotland

Scottish geologists and non-Scots working in Scotland have played an important part in the development of the science, especially during its pioneering period in the late 18th century and 19th century.[1]

- James Hutton (1726–1797), the "father of modern geology", was born in Edinburgh. His Theory of the Earth, published in 1788, proposed the idea of a rock cycle in which weathered rocks form new sediments and that granites were of volcanic origin. At Glen Tilt in the Cairngorm mountains he found granite penetrating metamorphic schists. This showed to him that granite formed from the cooling of molten rock, not precipitation out of water as the Neptunists of the time believed.[53] This sight is said to have "filled him with delight".[54] Regarding geological time scales he famously remarked "that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end".[55]

- John Playfair (1748–1819) from Angus was a mathematician who developed an interest in geology through his friendship with Hutton. His 1802 Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth were influential in the latter's success.[56]

- Edinburgh University. A president of the Geological Society from 1815 to 1817, he is best remembered for producing the first geological map of Scotland, published in 1836. 'MacCulloch's Tree', a 40-foot (12 m) high fossil conifer in the Mull lava flows, is named after him.[57][58]

- uniformitarianism and his interpretation of geologic change as the steady accumulation of minute changes over enormously long spans of time was a central theme in the Principles, and a powerful influence on the young Charles Darwin. (Robert FitzRoy, captain of HMS Beagle, loaned Darwin a copy of Volume 1 of the first edition just before they set out on the 'Voyage of the Beagle'.) Lyell is buried in Westminster Abbey.[59][60][61]

- Sir Roderick Murchison (1792–1871) was born in Ross and Cromarty and served under Wellesley in the Peninsular War. Knighted in 1846, his main achievements were the investigation of Silurian rocks published as The Silurian System in 1839 and of Permian deposits in Russia. The Murchison crater on the Moon and at least fifteen geographical locations on Earth are named after him.[62][63]

- evolution.[64]

- Andersonian College and Museum, Glasgow in 1859. His 1864 paper On the Physical Cause of the Changes of Climate during Glacial Epochs led to a position in the Edinburgh office of the Geological Survey of Scotland, as keeper of maps and correspondence, where Sir Archibald Geikie, encouraged his research. He was eventually to become a Fellow of the Royal Society.[65]

- Arthur Holmes (1890–1965) was born in England and became Regius Professor of Geology at the University of Edinburgh in 1943. His magnum opus was Principles of Physical Geology, first published in 1944, in which he proposed the idea that slow moving convection currents in the Earth's mantle created 'continental drift' as it was then called. He also pioneered the discipline of geochronology. He lived long enough to see the theory of plate tectonics become widely accepted, and he is regarded as one of the most influential geologists of the 20th century.[67]

Important sites

Siccar Point

Siccar Point, Berwickshire is world-famous as one of the sites that proved Hutton's views about the immense age of the Earth. Here Silurian rocks have been tilted almost to the vertical. Younger Carboniferous rocks lie unconformably over the top of them, dipping gently, indicating that an enormous span of time must have passed between the creation of the two beds. When Hutton and James Hall visited the site in 1788 their companion Playfair wrote:[10][68]

- On us who saw these phenomenon for the first time the impression will not easily be forgotten...We felt necessarily carried back to a time when the schistus on which we stood was yet at the bottom of the sea, and when the sandstone before us was only beginning to be deposited, in the shape of sand or mud, from the waters of the supercontinent ocean... The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far back into the abyss of time; and whilst we listened with earnestness and admiration to the philosopher who was now unfolding to us the order and series of these wonderful events, we became sensible how much further reason may sometimes go than imagination may venture to follow. —John Playfair (1805) Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. V, pt. III.[69]

Knockan Crag

The

Dob's Linn

Lapworth also had a prominent role to play in the fame of Dob's Linn, a small gorge in the Scottish Borders, which contains the 'golden spike' (i.e. the official international boundary or stratotype) between the Ordovician and Silurian periods. Lapworth's work in this area, especially his examination of the complex stratigraphy of the Silurian rocks by comparing fossil graptolites, was crucial in to the early understanding of these epochs.

Skye Cuillin

The Skye Cuillin mountains provide classic examples of glacial topography and were the subject of an early published account by James Forbes in 1846 (who had become a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh aged only nineteen).[75][76] He partnered Louis Agassiz on his trip to Scotland in 1840 and although they subsequently argued, Forbes went on to publish other important papers on Alpine glaciers.[77] In 1904 Alfred Harker published The Tertiary Igneous Rocks of Skye, the first detailed scientific study of an extinct volcano.[78][79]

Strontian

In the hills to the north of the village of Strontian the mineral strontianite was discovered, from which the element strontium was first isolated by Sir Humphry Davy in 1808.[80]

Staffa

The island of

Schiehallion

The Munro Schiehallion's isolated position and regular shape led Nevil Maskelyne to use the deflection caused by the mass of the mountain to estimate the mass of the Earth in a ground-breaking experiment carried out in 1774. Following Maskelyne's survey, Schiehallion became the first mountain to be mapped using contour lines.[81]

Rhynie

The village of

East Kirkton quarry

A disused

Wester Ross bolide

In 2008 the ejected material from a

See also

- British Geological Survey

- Geological groups of Great Britain

- Geologic timescale

- Coal measures

- Old Red Sandstone

- New Red Sandstone

- Geology of Orkney

References

- ^ a b Keay & Keay (1994) page 415.

- ^ University of Edinburgh - James Hutton Archived November 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) pages 415-422.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 124-31.

- ^ SNH Trends- seas Archived 2007-07-09 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003) pages 90-1.

- ^ a b Shepherd, Mike (2015). Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press.

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) page 867.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003) page 110.

- ^ a b c Gillen (2003) page 95.

- ^ "Southern Uplands Fault" Archived December 19, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ^ "Regional Geology, Southern Uplands - Map" Scottishgeology.com. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Murray, W. H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen.

- ^ Murray, W.H. (1977) The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland. London. Collins.

- ^ "Study Sees North Sea Tsunami Risk" Spiegel Online. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ Bondevik, Stein; Dawson, Sue; Dawson, Alastair; Lohne, Øystein. (5 August 2003) "Record-breaking Height for 8000-Year-Old Tsunami in the North Atlantic" Archived 2007-01-06 at the Wayback Machine(pdf) Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. Vol.84 Issue 31, pages 289-293. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ "Earthquakes in the Inverness Area" Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Inverness Royal Academy. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- ^ Gillen (2003) page 44.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 95.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 94.

- ^ a b c d McKirdy et al. (2007) page 68.

- ^ "Precambrian History of the UK" geologyrocks.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Sellar, W.D.H. (ed) (1993) Moray: Province and People. The Scottish Society for Northern Studies.

- ^ "Palaeozoic History of the UK: Cambrian to Silurian" geologyrocks.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Gillen (2003) pages 98 and 111.

- ^ Gillen (2003) pages 69, 73, 75, 88 and 95.

- ^ "Palaeozoic History of the UK: Cambrian to Silurian" Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b Butler, Rob (2000) The Moine Thrust Belt. Leeds University. Retrieved 27 January 2006.

- ^ "The Devonian Period (416 ~ 359 million years ago)" Scottishgeology.com. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ Gillen (2003) pages 110-119.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 124-130.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 132-135.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003) pages 120-5.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 141-144.

- ISBN 978-0-500-28573-2.

- ^ "The Permian & Triassic Periods (299 ~251 and 251 ~ 200 million years ago respectively)" Scottishgeology.com. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 146.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003) pages 133-7.

- ^ Gillen (2003) pages 138-9

- ^ "The Cretaceous Period (146 ~ 65 million years ago)" Scottish geology.com. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- S2CID 129576178.

- ^ Gillen (2003) page 142.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 150.

- ^ a b McKirdy et al. (2007) page 158.

- ISBN 0901702412.

- ^ "Tertiary" Fettes.com Retrieved 16 August 2007. Archived September 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 159 and 163-171.

- ^ "The Quaternary" Scottishgeology.com. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "Update to UKCIP02 sea level change estimates" (December 2005) UK Climate Impacts Programme. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ^ Smith, David E., and Fretwell, Peter T. "Scottish Sea Levels" Archived November 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine scottishsealevels.net. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Ross, Sinclair (1992) The Culbin Sands – Fact and Fiction. Aberdeen University Press.

- ^ "The Natural Environment: Machair". wildlifehebrides.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Robert Macfarlane (13 September 2003). "Glimpses into the abyss of time". The Spectator Review of Repcheck's "The Man Who Found Time".

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) page 531.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 61 and 115.

- ^ Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen (1856), reproduced in "Significant Scots" electricscotland.com. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 156.

- ^ Jones (1997) page 38.

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) page 641.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey.—A Survey of the Building." British History Online. Retrieved 12 August 2007

- ^ "Lyell, Sir Charles (1797-1875)" Archived 2008-03-27 at the Wayback Machine About Darwin.com. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ISBN 0-9546829-0-4.

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) page 717.

- ^ "Who Was He, Then?" Discover Hugh Miller. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 77.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 86.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 54.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 253.

- ^ John Playfair (1999). "Hutton's Unconformity". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. V, pt. III, 1805, quoted in Natural History, June 1999.

- S2CID 129572998.

- ^ Peach, B.N., Horne, J., Gunn, W., Clough, C.T., and Hinxman, L.W., (1907) The Geological Structure of the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 110 and 121-122.

- ^ "Welcome to North West Highland Geopark Archived 2008-01-25 at the Wayback Machine northwest-highlands-geopark.org.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 88.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 638.

- ^ Forbes, James D. (1846) Notes on the topography and geology of Cuchullin Hills in Skye, and on traces of ancient glaciers which they present. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal No. 40. Pages 76-99.

- ^ Forbes, James D. (1846) On the Viscous Theory of Glacier Motion Abstracts of the Papers Communicated to the Royal Society of London, Vol. 5, 1843 - 1850. Pages 595-596.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 164-5 and 280.

- ^ Harker, Alfred, (1904) The Tertiary Igneous Rocks of Skye. Geological Survey of Scotland Memoir.

- ^ "Strontian" Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Davies, R.D. (1985) A Commemoration of Maskelyne at Schiehallion. Royal Astronomical Society Quarterly Journal. Vol. 26 No.3 Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Rice, C. M., Ashcroft, W. A., Batten, D. J., Boyce, A. J., Caulfield, J. B. D., Fallick, A. E., Hole, M. J., Jones, E., Pearson, M. J., Rogers, G., Saxton, J. M., Stuart, F. M., Trewin, N. H. & Turner, G. (1995) A Devonian auriferous hot spring system, Rhynie, Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London, 152. Pages 229-250.

- ^ "Absolute age and underlying cause of hot-spring activity at Rhynie, NE Scotland from high precision geo-chronology" (pdf) NIGL Annual Report for 2003-4. Annex 7: Scientific highlights for the 2003-2004 year. p. 42.

- ^ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 132.

- ^ Amor, Kenneth; Hesselbo, Stephen P.; Porcelli, Don; Thackrey, Scott; and Parnell, John (April 2008) "A Precambrian proximal ejecta blanket from Scotland" (pdf) Geological Society of America. Volume 36:4 pp. 303–306.

Cited references:

- Gillen, Con (2003) Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing.

- Jones, Rosalind (1997) Mull in the Making. Aros. R Jones. ISBN 0-9531890-0-7

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins.

- McKirdy, Alan; Gordon, John; Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-357-0

- Shepherd, Mike. (2015) Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press.

General reference:

- "Scottish Geology" Scottishgeology.com. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

External links

- Geology of Scotland – Earthwise – British Geological Survey. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- Scottish Geology Trust. Retrieved 2024-01-06.