User:Blackknight12/sandbox

| History of Sri Lanka | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Chronicles | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Periods | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| By Topic | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

The history of Sri Lanka covers Sri Lanka and the history of the Indian subcontinent and its surrounding regions of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Prehistoric Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.

According to the Mahāvamsa, a chronicle written in Pāḷi, the preceeding inhabitants of Sri Lanka were said to be Yakkhas and Nagas.[4] Sinhalese history traditionally starts in 543 BC with the arrival of Prince Vijaya, a semi-legendary prince who sailed with 700 followers to the island, after being expelled from the Vanga Kingdom, in present-day Bengal.[5] Prince Vijaya thereafter established the Sinhala Kingdom ushering in the historical period of Sri Lanka. During the Anuradhapura period (377 BCE–1017) Buddhism was introduced in the 3rd century BCE by Mahinda, son of Indian emperor Ashoka.[6]

Due to the island's close proximity to Southern India, Dravidian influence on Sri Lankan politics and trade had been very active since the third century BC. Trade relations between the Anuradhapura Kingdom and southern India existed very probably from an early time.[7][8] South Indian attempts at usurping power of the Anuradhapura Kingdom appears to have been at least motivated by the prospect of influencing the country's lucrative external trade.[7] From about the fifth century AD onwards, Tamil mercenaries were brought to the island for the service of the Sinahalese monarchs.[7][9] This would play a small part in the fall of the Anuradhapura Kingdom in the 11th century with the Chola conquest.

Invasion of the Anuradhapura Kingdom by

The

The

The Portuguese lost their possessions in Sri Lanka due to

Geographical background

Sri Lanka lies on the Indian Plate, a major tectonic plate that was formerly part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[17] It is in the Indian Ocean southwest of the Bay of Bengal, between latitudes 5° and 10°N, and longitudes 79° and 82°E.[18][19] Sri Lanka is separated from the mainland portion of the Indian subcontinent by the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait. According to Hindu mythology, a land bridge existed between the Indian mainland and Sri Lanka. It now amounts to only a chain of limestone shoals remaining above sea level.[20] Legends claim that it was passable on foot up to 1480 AD, until cyclones deepened the channel.[21][22] Portions are still as shallow as 1 metre (3 ft), hindering navigation.[23] The island consists mostly of flat to rolling coastal plains, with mountains rising only in the south-central part. The highest point is Pidurutalagala, reaching 2,524 metres (8,281 ft) above sea level.

Sri Lanka has 103 rivers. The longest of these is the Mahaweli River, extending 335 kilometres (208 mi).[24] These waterways give rise to 51 natural waterfalls of 10 meters or more. The highest is Bambarakanda Falls, with a height of 263 metres (863 ft).[25] Sri Lanka's coastline is 1,585 km long.[26] Sri Lanka claims an Exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles, which is approximately 6.7 times Sri Lanka's land area. The coastline and adjacent waters support highly productive marine ecosystems such as fringing coral reefs and shallow beds of coastal and estuarine seagrasses.[27]

Sri Lanka has 45 estuaries and 40 lagoons.[26] Sri Lanka's mangrove ecosystem spans over 7,000 hectares and played a vital role in buffering the force of the waves in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.[28] The island is rich in minerals such as ilmenite, feldspar, graphite, silica, kaolinite, mica and thorium.[29][30] Existence of petroleum and gas in the Gulf of Mannar has also been confirmed and the extraction of recoverable quantities is underway.[31]

Lying within the Indomalayan realm, Sri Lanka is one of 25 biodiversity hotspots in the world.[32] Although the country is relatively small in size, it has the highest biodiversity density in Asia.[33] A remarkably high proportion of the species among its flora and fauna, 27% of the 3,210 flowering plants and 22% of the mammals (see List), are endemic.[34] Sri Lanka has declared 24 wildlife reserves, which are home to a wide range of native species such as Asian elephants, leopards, sloth bears, the unique small loris, a variety of deer, the purple-faced langur, the endangered wild boar, porcupines and Indian pangolins.[35]

Flowering

During the Mahaweli Development programme of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Sri Lanka, the government set aside four areas of land totalling 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi) as national parks. Sri Lanka's forest cover, which was around 49% in 1920, had fallen to approximately 24% by 2009.[38][39]

Overview

Periodization of Sri Lanka history:

| Dates | Period | Period | Span (years) | Subperiod | Span (years) | Main government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300,000 BP–~1000 BC | Prehistoric Sri Lanka | Stone Age

|

– | 300,000 | Unknown | |

| Bronze Age | – | |||||

| ~1000 BC–543 BC | Iron Age

|

– | 457 | |||

| 543 BC–437 BC | Ancient Sri Lanka | Pre-Anuradhapura | – | 106 | Monarchy | |

| 437 BC–463 AD | Anuradhapura | 1454 | Early Anuradhapura

|

900 | ||

| 463–691 | Middle Anuradhapura

|

228 | ||||

| 691–1017 | Post-classical Sri Lanka | Late Anuradhapura

|

326 | |||

| 1017–1070 | Polonnaruwa | 215 | Chola conquest | 53 | ||

| 1055–1232 | 177 | |||||

| 1232–1341 | Transitional | 365 | Dambadeniya

|

109 | ||

| 1341–1412 | Gampola

|

71 | ||||

| 1412–1597 | Early Modern Sri Lanka | Kotte

|

185 | |||

| 1597–1815 | Kandyan | – | 218 | |||

| 1815–1948 | Modern Sri Lanka | British Ceylon | – | 133 | Colonial monarchy | |

| 1948–1972 | Contemporary Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka since 1948 | 76 | Dominion | 24 | Constitutional monarchy |

| 1972–present | Republic | 52 | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Prehistoric Sri Lanka

Pre Iron Age (Pre ~1000 BC)

The pre-history of Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.

One of the first written references to the island is found in the Indian

Early inhabitants of Sri Lanka were probably ancestors of the

, and other valuables.Iron Age (~1000 BC–543 BC)

The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1200 BCE, if not earlier[49][50] The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon-dated to c. 1000–800 BCE at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya.[51][52][53][54] It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.[55] Archaeological evidence for the beginnings of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka is found at Anuradhapura, where a large city–settlement was founded before 900 BCE. The settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE, but by 700 BCE it had expanded to 50 hectares.[56] A similar site from the same period has also been discovered near Aligala in Sigiriya.[57]

The hunter-gatherer people known as the

inhabited the island prior to the Indo-Aryan migration.Pre-Anuradhapura period (543–437 BCE)

The Pali chronicles, the

According to the

The

Vijaya was made the prince-regent by his father, but he and his band of followers became notorious for their violent deeds. After their repeated complaints failed to stop Vijaya's acts, the prominent citizens demanded that Vijaya be put to death. King Sinhabahu then decided to expel Vijaya and his 700 followers from the kingdom. The men's heads were half-shaved and they were put on a ship that was sent forth on the sea. The wives and children of these 700 men were also sent on separate ships. Vijaya had his followers landed at a place called Supparaka; the women landed at a place called Mahiladipaka, and the children landed at a place called Naggadipa. Vijaya's ship later reached Sri Lanka, on the North west coast of present-day

Vijaya tied a protective (

As Vijaya and Kuveni were sleeping, he woke up to sounds of music and singing. Kuveni informed him that the island was home to Yakkhas, who would kill her for giving shelter to Vijaya's men. She explained that the noise was because of wedding festivities in the Yakkha city of Sirisavatthu. With Kuveni's help, Vijaya defeated the Yakkhas. Vijaya and Kuveni had two children: Jivahatta and Disala. Vijaya established the Kingdom of Tambapanni. The new community established by him were now called Sinhala (සිංහල) after Sinhabahu.[73][74][71][75] And the island itself became to be known Sinhala-dipa; "the island of the Sinhalese". It is from this name that subsequent names for the island, i.e. Serendiva, Serendip, Ceilão, Zeilan, Ceylan, Ceylon were formed. To the Sinhalese the island would be always known as Lanka.[18]

Vijaya's ministers and other followers established several new villages. For example, Upatissa established Upatissagāma on the bank of the Gambhira river, north of Anuradhagama. His followers decided to formally consecrate him as king, but for this he needed a queen of the same rank, an Aryan (noble). Vijaya's ministers, therefore, sent emissaries with precious gifts to the city of Madhura, which was ruled by a Pandu king.[note 1] The king agreed to send his daughter as Vijaya's bride. He also requested other families to offer their daughters as brides for Vijaya's followers. Seven hundred daughters of the principal nobles came along with the Princess.[76] The Pandu king sent to Sri Lanka his own daughter, other women (including a hundred maidens of noble descent), craftsmen, a thousand families of 18 guilds, elephants, horses, waggons, and other gifts. This group landed in Sri Lanka, at a port known as Mahatittha.[77][71] Vijaya married the princess and was consecrated as King with great splendour. The other Pandu ladies were bestowed on the King's minister's, according to their grades, or castes. This is the first time in Sri Lankan history castes are mentioned. Though the system could have also come with Vijaya and his settlers.[78][71] Dipavamsa also omits mention of the South Indian princess.[79]

Vijaya then requested Kuveni, his Yakkhini queen, to leave the community, saying that his citizens feared supernatural beings like her. He offered her money, and asked her to leave their two children, Jivahatta and Disala, behind. But Kuveni took the children along with her to the Yakkha city of Lankapura. She asked her children to stay back, as she entered the city, where other Yakkhas recognized her as a traitor. She was suspected of being a spy, and was killed by a Yakkha. On advice of her maternal uncle, the children fled to Sumanakuta (identified with Sri Pada). In the Malaya region of Sri Lanka, they became husband-wife and gave rise to the Pulinda race (identified with the Vedda people).[note 2][80][71] The Vedda however are probably with little doubt the earliest inhabitants of Sri Lanka.[81]

Vijaya (543–505 BC) reigned for 38 years but had no other children after Kuveni's departure. Nothing much of significance took place during his reign.[82] When he grew old, he became concerned that he would die heirless. So, he decided to bring his twin brother Sumitta from India, to govern his kingdom. He sent a letter to Sumitta, but by the time he could get a reply, he died. The monarchy was succeeded by his chief minister Upatissa (505–504 BC) who became regent and governed the kingdom from Upatissagāma for a year, while awaiting a reply. Meanwhile, in Sinhapura, Sumitta had become the king, and had three sons. His queen was a daughter of the king of Madda (possibly Madra). When Vijaya's messengers arrived, he was himself very old. So, he requested one of his sons to depart for Sri Lanka. His youngest son, Panduvasdeva (504–474 BC), volunteered to go. Panduvasdeva and 32 sons of Sumitta's ministers reached Sri Lanka, where Panduvasdeva became the new ruler.[83][82][84]

Panduvasdeva married an Indian princess,

Abhaya (474–454 BC) succeeded his father Panduvasdeva. The oldest of 10 sons, Abhaya appears to have been a weak and indulgent king. His reign was noted for a rebellion caused by his nephew Pandukabhaya who would go to war with his uncles. Upon losing the battle Abhaya sent a letter to the prince in secret conferring on him the rule of the country south of the river, sharing sovereignty of Sri Lanka. Hearing of this plan angered Abhaya's brothers, Pandukabhaya's uncles, who compelled Abhaya to abdicate and elected Prince Tissa (454–437 BC), the next in line, as regent.[87][88] Tissa was not archknowledged universally as the Sinhalese king, remained as regent while the war continued. The Nineteen Years' War (458–439 BC) ended with the Battle of Labugamaka where with the aid of the Yakkhas and others, Pandukabhaya slew eight of his uncles who were against him.[89][90][91] He took the capital Upatissagāma and preceeded to Anuradhagama where in 438 BC he built it as the new capital of Sri Lanka, renaming it Anuradhapura.[note 3][92]

Anuradhapura period (437 BCE–1017)

Early Anuradhapura period (437 BC–463 AD)

Succeeding kingdoms of Sri Lanka would maintain a large number of

Sri Lanka first experienced a foreign invasion during the reign of

The

.Sri Lanka was the first Asian country known to have a female ruler:

The

During the reign of

Middle Anuradhapura period (463–691)

Sri Lankan monarchs undertook some remarkable construction projects such as Sigiriya, the so-called "Fortress in the Sky", built during the reign of Kashyapa I of Anuradhapura, who ruled between 477 and 495. The Sigiriya rock fortress is surrounded by an extensive network of ramparts and moats. Inside this protective enclosure were gardens, ponds, pavilions, palaces and other structures.[112][113]

The 1,600-year-old Sigiriya frescoes are an example of ancient Sri Lankan art at its finest.[112][113] They are one of the best preserved examples of ancient urban planning in the world.[114] They have been declared by UNESCO as one of the seven World Heritage Sites in Sri Lanka.[115] Among other structures, large reservoirs, important for conserving water in a climate with rainy and dry seasons, and elaborate aqueducts, some with a slope as finely calibrated as one inch to the mile, are most notable. Biso Kotuwa, a peculiar construction inside a dam, is a technological marvel based on precise mathematics that allows water to flow outside the dam, keeping pressure on the dam to a minimum.[116]

Late Anuradhapura period (691–1017)

Polonnaruwa period (1017–1232)

Chola conquest (1017–1070)

A partial consolidation of Chola power in

Polonnaruwa period (1055–1232)

Following a

Vijayabāhu I (1055–1110), descended from, or at least claimed to be descended from the

Upon Vijayabāhu I's death a succession dispute jeopardized the recovery from the Chola conquest. His successors proved unable to consolidate power plunging the kingdom into a period of civil war, from which Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186), a closely related royal emerged.[132] Parākramabāhu I established control over the island and secured his recognition as Vijayabāhu's heir by obtaining the Tooth and bowl relics of the Buddha, which by now had become essential to the legitimacy of royal authority in Sri Lanka.[132]

By the time of the Polonnaruwa period the Sinhalese has centuries of experience in irrigation technology behind them and so the Polonnaruwa kings, especially Parākramabāhu the Great, made distinguished contributions of their own at honing these techniques to cope with the special requirements of the immense irrigation projects at the time.[133] Sri Lanka's irrigation network was extensively expanded during the reign of Parākramabāhu the Great.[134] He built 1470 reservoirs – the highest number by any ruler in Sri Lanka's history – repaired 165 dams, 3910 canals, 163 major reservoirs, and 2376 mini-reservoirs.[134] His most famous construction is the Parakrama Samudra, the largest irrigation project of medieval Sri Lanka. Having re-established the political unification of the island, Parākramabāhu continued Vijayabāhu policy in keeping a tight check on separatist tendencies within the island, especially in Rohana where particularism was a deeply ingrained political tradition. Parākramabāhu faced a formidable rebellion in 1160 as Rohana did not accept its loss of autonomy lightly. A rebellion in 1168 in Rajarata also manifested. Both were put down with great severity and all vestiges of its former autonomy purposefully eliminated. Particularism was now much less tolerated than it was during the Anuradhapura period. This new over-centralization of authority in Polonnaruwa would however work against the Sinhalese in the future and the country would eventually pay dearly as a result.[135]

Parākramabāhu's reign is memorable for two major campaigns – in the south of India as part of a Pandyan war of succession, and a punitive strike against the kings of Ramanna (Myanmar) for various perceived insults to Sri Lanka.[136][137] Parākramabāhu I was the last of the great ancient Sri Lankan kings.[135] His reign is considered as a time when Sri Lanka was at the height of its power.[138][137] Parākramabāhu had no sons, which complicated the the problem of succession upon his death. Amid the succession crisis a scion of a foreign dynasty, Niśśaṅka Malla established his claims as a Prince of Kalinga,[note 6] claiming to be chosen and trained for the succession by Parākramabāhu himself.[135] He was also either the son-in-law or nephew of Parākramabāhu.[139]

Niśśaṅka Malla (1187–1196) was the first monarch of the House of Kalinga and the only Polonnaruwa monarch to rule over the whole island after Parākramabāhu. His reign gave the country a brief decade of order and stability before the speedy and catastrophic break-up of the hydraulic civilisations of the dry zone.[135] With his death there was a renewal of political dissension, now complicated by dynastic disputes.[140] Though he and his predecessors Vijayabāhu and Parākramabāhu achieved much in state building. The conspicuous lack of restraint, especially that of Parākramabāhu, in combination with an ambitious and venturesome foreign policy, and an expensive diversion of state resources towards public works projects, sapped the strength of the country and contributed to its sudden and complete collapse.[135]

The House of Kalinga would maintain itself in power, but only with the support of an influential faction within the country. Their survival owed much to the inability of the factions opposing them to come up with an aspirant to the throne with a politically viable claim, or sufficient durability once installed in power, therefore the House of Kalinga's hold on the throne was inherently precarious. On three occasions, the queen of Parākramabāhu, Lilāvatī, was raised to the throne out of desperation.[140] The factional struggle and political instability attracted the attention of South Indian adventures bent on plunder, culminating in the devastating campaign of pillage under Māgha of Kalinga (1215–1236), claiming the inheritance of the kingdom through his kinsman who reigned before.[141][140]

Māgha, a bigoted Hindu, persecuted Buddhists, despoiling the temples and giving away lands of the Sinhalese to his followers.[141] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of the Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power.[142] Māgha's rule of 21 years and its aftermath are a watershed in the history of the island, creating a new political order.[140] After his death in 1255 Polonnaruwa ceased to be the capital, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power and from then on there were two, or sometimes three rulers existing concurrently.[140][143] Parakramabahu VI of Kotte (1411-1466) would be the only other Sinhalese monarch to establish control over the whole island after this period.[140] The Rajarata, the traditional location of the Sinhalese kingdom and Rohana, the previously autonomous subregion were abandoned. Two new centers of political authority emerged as a result of the fall of the Polonnaruwa kingdom.

In the face of repeated South Indian invasions the Sinhalese monarchy and people retreated into the hills of the wet zone, further and further south, seeking primarily security. The capital was abandoned and moved to

Transitional period (1232–1597)

Early Transitional period (1232–1521)

Capital at Dambadeniya

The next three centuries were marked by kaleidoscopic shifting of the national capital from the north central to the south and central of the island.[141] The Jaffna kingdom came under the rule of the south on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest by Parâkramabâhu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal. He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467.[146]

Capital at Gampola

The capital was moved to Gampola by Buwanekabahu IV, he is said to be the son of Sawulu Vijayabāhu. During this time, a muslim traveller and geographer named Ibn Battuta came to Sri Lanka and wrote a book about it. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya is the main building made in the Gampola Kingdom period. The Lankatilaka Viharaya is also a main building built in Gampola.

Chinese admiral

Capital at Kotte

By the Sixteenth century the population of the island was approximately 750,000, the majority, 400-450 thousand lived in the

During this time the Portuguese entered into the internal politics of Sri Lanka. Largely by accident, first contact between the two nations was in 1505-06. But it was not until 1517-18 that the Portuguese sought to establish a fortified trading settlement in order to establish control over the island's Cinnamon trade, as opposed to territorial conquest.[156] The building of a fort, near Colombo, had to be given up due popular hostility that was fanned by Moorish traders, who had established themselves on the island and controled a large portion of its external trade.[156] The Portuguese at no stage established dominance over the politics of South Asia, but sought to do so over its commerce by means of subjugation through naval power. Using their superior technology and sea power at points of weakness or divisions, the Portuguese would attain influence in greater proportions to their actual strength. Portuguese anxiety to establish a Bridgehead in Sri Lanka to control the island's Cinnamon trade drew them further into the politics of Sri Lanka.[157]

Kotte suffered from persistant succession disputes during this time. Though all were subordinate to the emperor of Kotte, brothers of the king would take the title Raja (king) and rule parts of the kingdom. This practice was possibly tollerated to humour princes who had some claim to the throne by giving them positions of responsibility, and the belief that having loyal relatives in outlying disticts afforded some security to the king. However this political structure inevitably led to its own weakening in the long run, as those princes, who could, virtually administered the areas they claimed as autonomous principalities.[158]

Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1521–1597)

In 1521 the Vijayabā Kollaya was one such and the most eventful of succession disputes in the kingdom and would trigger the most chaotic period in the history of Sri Lanka. Vijayabāhu VI, who had four sons by two wives, sought to select his youngest son for the succession of the kingdom. In reaction the three older brothers assassinated their father, with the assistance of the Kandyan ruler, and divided the kingdom among themselves. With this partition the fragmentation of the Sri Lankan polity seemed well beyond the capacity of any statesman to repair.[158] The Kandyan ruler took advantage of the situation in a cynical and shrewd move to aggrevate the political instability as an opportunity to assert their independance from the control of Kotte. Kanday ruler Jayavira Bandara (1511–52) readily aided the three princes against their father, and it was clear the decline of the Kingdom of Kotte was necessary for the rise of the Kingdom of Kandy.[156]

Kandyan period (1597–1815)

When the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen landed in 1602, the king of Kandy appealed to him for help.

In 1619, succumbing to attacks by the Portuguese, the independent existence of Jaffna kingdom came to an end.[159]

During the reign of the

The Kingdom of Kandy was the last independent monarchy of Sri Lanka.

Eventually, with the support of

British Ceylon period (1815–1948)

As a result of the

The Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1833 ushered in a period of reformist zeal that would never again be matched during British rule.[169] They introduced a utilitarian and liberal political culture to the country based on the rule of law and amalgamated the Kandyan and maritime provinces as a single unit of government. An executive council and a legislative council were established, later becoming the foundation of a representative legislature. By this time, experiments with coffee plantations were largely successful.[170]

Soon coffee became the primary commodity export of Sri Lanka. However falling coffee prices as a result of the

By the end of the 19th century, a new educated social class transcending race and caste arose through British attempts to staff the Ceylon Civil Service and the legal, educational, and medical professions.[173] New leaders represented the various ethnic groups of the population in the Ceylon Legislative Council on a communal basis. Buddhist and Hindu revivalism reacted against Christian missionary activities.[174] The first two decades in the 20th century are noted by the unique harmony among the Sinhalese and Tamil political leadership, which dissipated by the 1920s.[175]

In 1919, major Sinhalese and Tamil political organisations united to form the Ceylon National Congress (CNC), under the leadership of Ponnambalam Arunachalam,[177] pressing colonial masters for more constitutional reforms. But without massive popular support, and with the governor's encouragement for "communal representation" by creating a "Colombo seat" that dangled between Sinhalese and Tamils, the Congress lost momentum towards the mid-1920s.[178]

The Donoughmore reforms of 1931 repudiated the communal representation and introduced universal adult franchise[note 8]. This step was strongly criticised by the Tamil political leadership, who realised that they would be reduced to a minority in the newly created State Council of Ceylon, which succeeded the legislative council.[179][180] In 1937, Tamil leader G. G. Ponnambalam demanded a 50–50 representation (50% for the Sinhalese and 50% for other ethnic groups) in the State Council. However, this demand was not met by the Soulbury reforms of 1944–45.

Sri Lanka was a front-line British base against the Japanese during

The Sinhalese leader D. S. Senanayake left the CNC on the issue of independence, disagreeing with the revised aim of 'the achieving of full independance' in favour of Dominion status, although his real reasons were more subtle.[181] He subsequently formed the United National Party (UNP) in 1946,[182] when a new constitution was agreed on, based on the behind-the-curtain lobbying of the Soulbury commission. At the elections of 1947, the UNP won a minority of seats in parliament, but cobbled together a coalition with the Sinhala Maha Sabha party of Solomon Bandaranaike and the Tamil Congress of G.G. Ponnambalam. The successful inclusions of the Tamil-communalist leader Ponnambalam, and his Sinhalese counterpart Bandaranaike were a remarkable political balancing act by Senanayake.

Sri Lanka (1948–present)

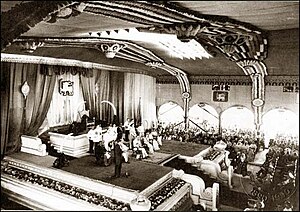

The Soulbury constitution ushered in Dominion status, with independence proclaimed on 4 February 1948.[183] D. S. Senanayake became the first Prime Minister of Ceylon.[183] Prominent Tamil leaders including Ponnambalam and Arunachalam Mahadeva joined his cabinet.[184] The British Navy remained stationed at Trincomalee until 1956. A countrywide popular demonstration against withdrawal of the rice ration, known as 1953 Hartal, resulted in the resignation of prime minister Dudley Senanayake.[185]

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was elected prime minister in 1956. His three-year rule had a profound impact through his self-proclaimed role of "defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture".[186] He introduced the controversial Sinhala Only Act, recognising Sinhala as the only official language of the government. Although partially reversed in 1958, the bill posed a grave concern for the Tamil community, which perceived in it a threat to their language and culture.[187][188][189]

The

The government of

Lapses in foreign policy resulted in India strengthening the Tigers by providing arms and training.

The 2004 Asian tsunami killed over 35,000 in Sri Lanka.[208] From 1985 to 2006, the Sri Lankan government and Tamil insurgents held four rounds of peace talks without success. Both LTTE and the government resumed fighting in 2006, and the government officially backed out of the ceasefire in 2008. In 2009, under the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the LTTE and re-established control of the entire country by the Sri Lankan Government.[209] Overall, between 60,000 and 100,000 people were killed during the 26 years of conflict.[210][211]

Forty thousand Tamil civilians

According to the Ministry of Resettlement, most of the displaced persons had been released or returned to their places of origin, leaving only 6,651 in the camps as of December 2011.[218] In May 2010, President Rajapaksa appointed the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) to assess the conflict between the time of the ceasefire agreement in 2002 and the defeat of the LTTE in 2009.[219][220] Sri Lanka has emerged from its 26-year war to become one of the fastest growing economies of the world.[221][222]

See also

Notes

- ^ Madhura is identified with Madurai, a city in South India; Pandu is identified with the Pandyas

- Pulindasof India

- ^ After one of Vijaya's ministers and Pandukabhaya's own great-uncle who both resided there and where both named Anuradha.

- ^ As noted by its native name of Kandavura Nuvara (the camp city)

- ^ Considered as one of the oldest Hindu shrine in Polonnaruwa founded during Chola occupation built during 1015-1044[131]

- ^ The birthplace of Prince Vijaya and the ancestors of the Sinhalese.

- ^ The land between Anuradhapura and Jaffna

- ^ The franchise stood at 4% before the reforms

References

Citations

- ^ a b Deraniyagala 1996.

- ^ Geiger 1930, p. 228.

- ^ Gunasekara 1900.

- ^ a b c Coming of Vijaya 2019.

- ^ a b Geiger 1930, p. 208.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Pieris 2007.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Sastri 1935, p. 172–173.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1994, p. 7–9.

- ^ Kulke, Kesavapany & Sakhuja 2009, p. 195–.

- ^ Gunawardena 2005, p. 71–.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 409.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 161.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Stein 1994.

- ^ a b c Blaze 1933, p. 2.

- ^ latlong2019.

- ^ BBC 2007.

- ^ Garg 1992, p. 142.

- ^ Rediff.com 2014.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Adam's Bridge 2015.

- ^ Aves 2003, p. 372.

- ^ Lonely Planet 2014.

- ^ a b United Nations Environment Programme 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization 2014.

- ^ International Union for Conservation of Nature 2014.

- ^ indexmundi.com 2009.

- ^ Vitharana 2008.

- ^ Cairn Lanka 2009, p. iv–vii.

- ^ Mittermeier, Myers & Mittermeier 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Environment Sri Lanka 2014.

- ^ news.mongabay.com 2012.

- ^ Ecotourism Sri Lanka 2014.

- ^ earthtrends.wri.org 2007, p. 4.

- ^ UNESCO 2006.

- ^ srilankanwaterfalls.net 2009.

- ^ MSN Encarta Encyclopedia 2009.

- ^ angelfire.com 2014.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1986, p. 165–265.

- ^ De Silva 1981, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 454.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 4.

- ^ Keshavadas 1988.

- ^ Parker 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Edirisinghe 2009.

- ^ Deraniyagala 2014.

- ^ ParPossehlker 1990.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 734.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 709-29.

- ^ Karunaratne & Adikari 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Mogren 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Coningham 1999.

- ^ Lankalibrary.com 2012.

- ^ Deraniyagala 2007.

- ^ Dailynews.lk 2008.

- ^ Holt 2011, p. 53-56.

- ^ Ranwella 2000.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 6.

- ^ Ariyadasa 2015.

- ^ The Mahavamsa 2019.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 5.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 7.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e The Consecrating of Vijaya 2019.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 8.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 8.

- ^ Wanasundera 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 9.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 10.

- ^ Spencer 2002, p. 74–77.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 10-11.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 11.

- ^ The Consecrating of Panduvasudeva 2019.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Codrington 1926, p. 9.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 18.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 14.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 10.

- ^ worldheritagesite.org 2004.

- ^ mysrilankaholidays.com 2014.

- ^ Perera 2014.

- ^ Holt 2004, p. 795–799.

- ^ The Mahavamsa 2014.

- ^ buddhanet.net 2014.

- ^ Maung Paw, p. 6.

- ^ Gunawardana 2012.

- ^ beyondthenet.net 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Starr 1956, p. 27–30.

- ^ Curtin 1984, p. 100.

- ^ De Silva 2014.

- ^ Sarachchandra 1977, p. 121–122.

- ^ Lopez 2013, p. 200.

- ^ sltda.gov.lk 2014.

- ^ a b lankalibrary.com 2014.

- ^ Weerakkody 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Flickr 2008.

- ^ Maung Paw, p. 7.

- ^ a b Ponnamperuma 2013.

- ^ a b Bandaranayake 1999.

- ^ Bandaranayake 1974, p. 321.

- ^ AsiaExplorers.com 2014.

- ^ slageconr.net 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Siriweera 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 411.

- ^ a b Spencer 1976, p. 416.

- ^ a b c Sastri 1935, p. 199–200.

- ^ a b c Spencer 1976, p. 417.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 741.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 81-2.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 57.

- ^ Lambert 2014.

- ^ Bokay 1966, p. 93–95.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 96.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 92.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 99.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 105.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 83.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 93.

- ^ a b Herath 2002, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e De Silva 2005, p. 84.

- ^ International Lake Environment Committee 2011.

- ^ a b ParakramaBahu I: 1153 - 1186 Eighth massa 2019.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 64.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f De Silva 2005, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Codrington 1926, p. 67.

- ^ a b Indrapala 1969, p. 16.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 76.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Holt 1991, p. 304.

- ^ South East Aisa in Ming Shi-lu 2005.

- ^ Voyages of Zheng He 1405–1433 2015.

- ^ Ming Voyages 2015.

- ^ Admiral Zheng He 2014.

- ^ The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng 2015.

- ^ Zheng He 2015.

- ^ Pieris 2011.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 142.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 143.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 145.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 147.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 144.

- ^ Knox 1681, p. 19–47.

- ^ Anthonisz 2003, p. 37–43.

- ^ Bosma 2008.

- ^ a b c The Sunday Times 2014.

- ^ Dharmadasa 1992, p. 8–12.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 140.

- ^ Tambiah 1954, p. 65.

- ^ colonialvoyage.com 2014.

- ^ a b c scenicsrilanka.com 2014.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 173.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 338.

- ^ a b Nubin 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Wimalaratne 2014.

- ^ Mills 1964, p. 246.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 116–117.

- ^ Bond 1992, p. 11–22.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 387.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 480.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 386.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 389–395.

- ^ Hellmann-Rajanayagam 2014.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 423.

- ^ Atimes.com 2012.

- ^ Countrystudies.us, p. 246.

- ^ a b Sinhalese Parties 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 121–122.

- ^ Weerakoon 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 123.

- ^ Ganguly 2003, p. 136–138.

- ^ Schmid & Schroeder 2001, p. 185.

- ^ BBC News 2013.

- ^ Peebles 2006, p. 109–111.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 663.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 664.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 665.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 128–129.

- ^ De Silva 1997, p. 248–254.

- ^ Jayasuriya 1981.

- ^ Hoffman 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Gunaratna 1998.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 684.

- ^ Jayatunge 2010.

- ^ Sunday Times 1997.

- ^ Express India 1997.

- ^ Wijesinghe 2014.

- ^ Stokke & Ryntveit 2000, p. 285–304.

- ^ Gunaratna 1998, p. 353.

- ^ Asia Times-Chapter 30 2002.

- ^ lankanewspapers.com 2008.

- ^ WSWS.org 2005.

- ^ Weaver & Chamberlain 2009.

- ^ ABC 2009.

- ^ Olsen 2014.

- ^ Hindustan Times 2011.

- ^ Haviland 2010.

- ^ Burke 2010.

- ^ The Sunday Observer 2011.

- ^ Amnesty International 2009.

- ^ BBC 2009.

- ^ Ministry of Resettlement in Sri Lanka 2011, p. 2.

- ^ ReliefWeb 2010.

- ^ Mallawarachi 2011.

- ^ Business Insider 2014.

- ^ adaderana.lk 2011.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Oldenberg, Hermann, ed. (1879). The Dîpavaṃsa: An Ancient Buddhist Historical Record. London & Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate.

- Mahānāma; tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; tr. Bode, Mabel Haynes (1912). The Mahāvaṃsa, Or, The Great Chronicle of Ceylon. London: Oxford University Press.

- Dhammakitti; Ger tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; Eng tr. Rickmers, Christian Mabel (1929). Cūḷavaṃsa: Being the More Recent Part of the Mahāvaṃsa, Part 1. London: Oxford University Press.

- Gunasekara, B., ed. (1900). The Rajavaliya: Or a Historical Narrative of Sinhalese Kings. Colombo: George J. A. Skeen, Government Printer, Ceylon.

- Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Richard Chiswell.

Secondary sources

- Histories

- Parker, Henry (1909). Ancient Ceylon. London: Luzac & Co.

- Codrington, H. W. (1926). A Short History Of Ceylon. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Senaveratna, John M. (1930). The Story of the Sinhalese from the Most Ancient Times Up to the End of "the Mahavansa" Or Great Dynasty: Vijaya to Maha Sena, B.C. 543 to A.D.302. Colombo: W. M. A. Wahid & Bros. ISBN 9788120612716.

- Blaze, L. E. (1933). History of Ceylon (PDF) (Eighth ed.). Colombo: Christian literature society for India and Africa.

- Nicholas, Cyril Wace; Paranavitana, Senerat (1961). A Concise History of Ceylon: From the Earliest Times to the Arrival of the Portuguese in 1505. Ceylon University Press.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (December 1992). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective (1st ed.). Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 9789559159001.

- ISBN 9780520043206.

- Siriweera, W. I. (2002). History of Sri Lanka: From Earliest Times Up to the Sixteenth Century. Dayawansa Jayakody & Company. ISBN 9789555512572.

- ISBN 9789558095928.

- ISBN 9780313332050.

- Other Books

- All Ceylon Buddhist Congress (1956). The Betrayal of Buddhism: An Abridged Version of the Report of the Buddhist Committee of Inquiry. Dharmavijaya Press.

- ISBN 9780415229050.

- Institute for International Studies (Peradeniya, Sri Lanka) (1992). Jayasekera, P. V. J. (ed.). Security dilemma of a small state. South Asian Publishers. ISBN 9788170031482.

- ISBN 9788120618459.

- Arseculeratne, S. N. (1991). Sinhalese Immigrants in Malaysia & Singapore, 1860-1990: History Through Recollections. Colombo: K.V.G. De Silva & Sons. ISBN 9789559112013.

- Aves, Edward (2003). Sri Lanka. Footprint. ISBN 9781903471784.

- Bandaranayake, S. D. (1974). Sinhalese Monastic Architecture: The Viháras of Anurádhapura. ISBN 9789004039926.

- Bandaranayake, Senaka; Madhyama Saṃskr̥tika Aramudala (1999). Sigiriya: city, palace, and royal gardens. Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs. ISBN 9789556131116.

- Bond, George Doherty (1992). The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response. ISBN 9788120810471.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. Singapore: ISBN 9789971693732.

- Brohier, Richard Leslie (1933). The Golden Age Of Military Adventure In Ceylon 1817-1818. Colombo: Plâté limited.

- ISBN 9780262523332.

- Chattopadhyaya, Haraprasad (1994). Ethnic Unrest in Modern Sri Lanka: An Account of Tamil-Sinhalese Race Relations. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788185880525.

- Crusz, Noel (2001). The Cocos Islands Mutiny. ISBN 9781863683104.

- De Silva, R. Rajpal Kumar (1988). Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon 1602-1796: A Comprehensive Work of Pictorial Reference With Selected Eye-Witness Accounts. ISBN 9789004089792.

- ISBN 9780472102884.

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170223757.

- ISBN 9789558093009.

- Gunawardena, Charles A. (2005). Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka. ISBN 9781932705485.

- Herath, R. B. (2002). Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis: Towards a Resolution. ISBN 9781553697930.

- ISBN 9780231126991.

- Holt, John (1991). Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteśvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka. Oxford: ISBN 9780195064186.

- Holt, John (2011). The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. ISBN 9780822349822.

- Irons, Edward A. (2008). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Facts on File. ISBN 9780816054596.

- Jayasuriya, J. E. (1981). Education in the Third World: Some Reflections. Somaiya.

- Keshavadas, Sadguru Sant (1988). Ramayana at a Glance. ISBN 9788120805453.

- ISBN 9789812309372.

- Liyanagamage, Amaradasa (1968). The Decline of Polonnaruwa and the Rise of Dambadeniya (circa 1180 - 1270 A.D.). Department of Cultural Affairs.

- Mendis, Ranjan Chinthaka (1999). The Story of Anuradhapura: Capital City of Sri Lanka from 377 BC - 1017 Ad. Lakshmi Mendis. ISBN 9789559670407.

- Mills, Lennox A. (1964). Ceylon Under British Rule, 1795-1932. Cass. ISBN 9780714620190.

- ISBN 9788126906161.

- ISBN 9789686397581.

- Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. ISBN 9781590335734.

- Perera, Lakshman S. (2001). The Institutions of Ancient Ceylon from Inscriptions: From 831 to 1016 A.D., pt. 1. Political institutions. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. ISBN 9789555800730.

- Pieris, Paulus Edward (1918). Ceylon and the Hollanders, 1658-1796. Tellippalai: American Ceylon Mission Press.

- Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty, Limited. ISBN 9780987345110.

- Rambukwelle, P. B. (1993). Commentary on Sinhala kingship: Vijaya to Kalinga Magha. P.B. Rambukwelle. ISBN 9789559556503.

- Sarachchandra, B. S. (1977). අපේ සංස්කෘතික උරුමය [Our Cultural Heritage] (in Sinhala). V. P. Silva.

- Siriweera, W. I. (1994). A study of the economic history of pre-modern Sri Lanka. Vikas Pub. House. ISBN 9780706976212.

- ISBN 9780203407417.

- Tambiah, Henry Wijayakone (1954). The laws and customs of the Tamils of Ceylon. Tamil Cultural Society of Ceylon.

- Tinker, Hugh (1990). South Asia: A Short History. ISBN 9780824812874.

- Wanasundera, Nanda Pethiyagoda (2002). Sri Lanka. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761414773.

- Sastri, K. A (1935). The CōĻas. Madras: University of Madras.

- Journals

- Bokay, Mon (1966). "Relations between Ceylon and Burma in the 11th Century A.D". Artibus Asiae. Supplementum. 23. JSTOR: 93–95. JSTOR 1522637.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (8–14 September 1996). "Pre- and protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". XIII U. I. S. P. P. Congress Proceedings. 5. Lanka Library: 277–285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Geiger, Wilhelm (July 1930). "The Trustworthiness of the Mahavamsa". The Indian Historical Quarterly. 6 (2). Digital Library & Museum of Buddhist Studies: 205–228.

- JSTOR 43483465.

- Kennedy, K. A. R.; Disotell, Todd; Roertgen, W. J.; Chiment, J.; Sherry, J. (1986). "Biological anthropology of Upper Pleistocene Hominids from Sri Lanka: Batadomba Lena and Beli Lena Caves". Ancient Ceylon. 6.

- JSTOR 25201355.

- Sivasundaram, Sujit (April 2010). "Ethnicity, Indigeneity, and Migration in the Advent of British Rule to Sri LankaSujit SivasundaramEthnicity, Indigeneity, and Migration in the Advent of British Rule to Sri Lanka". The American Historical Review. 115 (2): 428–452. ISSN 0002-8762.

- Spencer, George W. (1976). "The Politics of Plunder: The Cholas in Eleventh-Century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3). JSTOR: 405–419. JSTOR 2053272.

- Starr, Chester G. (1956). "The Roman Emperor and the King of Ceylon". Classical Philology. 51 (1). JSTOR: 27–30. S2CID 161093319.

- Stokke, Kristian; Ryntveit, Anne Kirsti (2000). "The Struggle for Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka. Growth and Change". Growth and Change. 31 (2). ResearchGate: 285–304. .

- van der Kraan, Alfons (1999). "A Baptism of Fire: The Van Goens Mission to Ceylon and India, 1653-54" (PDF). Journal of the UNE Asia Centre. 2: 1–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-09.

- Weerakkody, D. P. M. (1987). "Sri Lanka and the Roman Empire". Modern Ceylon Studies. 2 (1 & 2). University of Peradeniya: 21–32.

- News

- AFP (20 May 2009). "Up to 100,000 killed in Sri Lanka's civil war: UN". ABC News. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Ariyadasa, Kanchana Kumara (18 October 2015). "Ancient graves during pre-Wijeya era found". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Bazeer, S. M. M. (18 November 2008). "1990, The War Year if Ethnic Cleansing Of The Muslims From North and the East of Sri Lanka". Lanka News Papers. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Burke, Jason (14 March 2010). "Sri Lankan Tamils drop demand for separate independent homeland". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Haviland, Charles (13 March 2010). "Tamil separate state call dropped". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Kohona, Palitha (4 March 2016). "Sri Lanka ready for the challenge". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Lopez, Linette (28 October 2011). "The 15 Fastest-Growing Economies In The World". Business Insider Australia. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Patranobis, Sutirtho (25 April 2011). "40,000 Tamil civilians killed in final phase of Lanka war, says UN report". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Pieris, Kamalika (13 November 2008). "Some domestic industries of ancient and medieval Sri Lanka". Daily News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Pieris, Kamalika (22 December 2007). "South Indian inflence in ancient and medieval Sri Lanka". The Island. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Pieris, Kamalika (4 November 2011). "Land tenure in 16th Century Sri Lanka". The Island. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Vitarana, Tissa (17 October 2008). "On the availability of sizeable deposits of thorium in Sri Lanka - Professor Tissa Vitarana | Asian Tribune". Asian tribune. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Warrier, Shobha (4 July 2007). "Ramar Sethu, a world heritage centre?". Rediff. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Weaver, Matthew; Chamberlain, Gethin (19 May 2009). "Sri Lanka declares end to war with Tamil Tigers". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Weerakoon, Batty (16 August 2008). "The Island-Saturday Magazine". The Island. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Wijesinghe, Sarath (8 July 2009). "For firmer and finer International Relations". Sri Lanka Guardian. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "A kingdom is born, a kingdom is lost". Sundaytimes. 4 March 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Gods row minister offers to quit". BBC News. 15 September 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Lanka among fastest growing millionaire populations - report". AdaDerana. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Sri Lanka profile - Timeline". BBC News. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Sri Lanka's displaced face uncertain future as government begins to unlock the camps". Amnesty International. 11 September 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Sri Lankan civilians 'not targeted', says report". Channel 4 News. 16 December 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "The Sunday Times On The Web - Plus". The Sunday Times. 19 January 1997. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "UN mourns Sri Lanka 'bloodbath'". BBC News. 11 May 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Uppermost in our minds was to save the Gandhis' name". Express India. 12 December 1997. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Web

- Jayatunge, Ruwan M. "LankaWeb – The Black July 1983 that Created a Collective Trauma". LankaWeb. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Lambert, Tim. "A Brief History of Sri Lanka". A World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Sunil, W. A. "One year after the tsunami, Sri Lankan survivors still live in squalour". World Socialist Web Site.

- Wade, Geoff, translator. "Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource, Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press". National University of Singapore. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weeraratna, Senaka (12 June 2005). "Repression of Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Portuguese (1505 - 1658)". vgweb.org. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Ancient Irrigation". Heritage Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Pahiyangala (Fa-Hiengala) Caves". www.angelfire.com. 24 June 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "ParakramaBahu I: 1153 - 1186 Eighth massa". coins.lakdiva.org. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Places in Sri Lanka with Categories". www.latlong.net. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Situation Report as of 15-12-2011" (PDF). Ministry of Resettlement in Sri Lanka. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Sri Lanka - Sinhalese Parties". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Sri Lanka - World War II and the Transition to Independence". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Sri Lanka". MSN Encarta Encyclopedia. Archived from the originalon 21 October 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "THE MAHAVAMSA » 06: Coming of Vijaya". The Mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "THE MAHAVAMSA » 07: Consecrating of Vijaya". The Mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "THE MAHAVAMSA » 08: King Panduvasudeva". The Mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "THE MAHAVAMSA » King Devanampiya Tissa (306 BC – 266 BC)". The Mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "The Ming Voyages". Columbia University. afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Waterworld: Ancient Sinhalese Irrigation, Sri Lanka". mysrilankaholidays.com.

- "The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng He". lankalibrary forum. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Deraniyagala, S.U. "Early Man and the Rise of Civilisation in Sri Lanka: the Archaeological Evidence". lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Gongale Goda Banda (1809–1849) : The leader of the 1848 rebellion". Wimalaratne, K.D.G. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Hospitals in ancient Sri Lanka". lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Keppetipola and the Uva Rebellion". lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Early Man and the Rise of Civilisation in Sri Lanka: the Archaeological Evidence". Lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Zheng He". world heritage site. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- "An interview with Dr. Ranil Senanayake, chairman of Rainforest Rescue International". news.mongabay.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Chronology of events related to Tamils in Sri Lanka (1500–1948)". Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar. National University of Malaysia. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Perera H. R. "Buddhism in Sri Lanka: A Short History". accesstoinsight.org. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Exploring Sigiriya Rock". AsiaExplorers.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Ruvanveli Seya – The Wonderous Stupa Built by Gods and Men" (PDF). beyondthenet.net. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Buddhism in Sri Lanka". buddhanet.net. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "The first British occupation and the definitive Dutch surrender". colonialvoyage.com. 18 February 2014.

- "Information Brief on Mangroves in Sri Lanka". International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Ecotourism Sri Lanka". www.environmentlanka.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "5 Coral Reefs of Sri Lanka: Current Status And Resource Management". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Sri Lanka Graphite Production by Year". indexmundi.com. 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Introducing Sri Lanka". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Rohan Gunaratna (December 1998). "International and Regional Implications of the Sri Lankan Tamil Insurgency" (PDF).

- "Three Dimensional Seismic Survey for Oil Exploration in Block SL-2007-01-001 in Gulf of Mannar–Sri Lanka" (PDF). Cairn Lanka. 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "The water regulation technology of ancient Sri Lankan reservoirs: The Bisokotuwa sluice" (PDF). slageconr.net. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Forests of Sri Lanka". srilankanwaterfalls.net. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- "World Heritage site: Anuradhapura". worldheritagesite.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2004. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "International relations in ancient and medieval Sri Lanka". Flickr. 21 January 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (10 November 2007). "Urban Landscape Dynamics Symposium". Uppsala Universitet. Archived from the original on 2007-11-10. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Adam's Bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Sri Lanka: President appoints Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission". ReliefWeb. 17 May 2010.

- Gunawardana, Jagath. "Historical trees: Overlooked aspect of heritage that needs a revival of interest". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Environment Sri Lanka". www.environmentlanka.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Ranwella, K (5–18 June 2000). "The so-called Tamil kingdom of jaffna". Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- "Depletion of coastal resources" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012.

- "Forests, Grasslands, and Drylands – Sri Lanka" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2007.

- De Silva; K. M. (July 1997). "Affirmative Action Policies: The Sri Lankan Experience" (PDF). International Center for Ethnic Studies. pp. 248–254. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011.

- "Parakrama Samudra". International Lake Environment Committee. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- "History of Sri Lanka and significant World events from 1796 AD to 1948". scenicsrilanka.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.