Genetic history of Africa

The genetic history of Africa summarizes the genetic makeup and population history of

Overview

The peoples of Africa are characterized by regional genetic substructure and heterogeneity, depending on the respective ethno-linguistic identity, and, in part, explainable by the "multiregional evolution" of modern human lineages in various multiple regions of the African continent, as well as later admixture events, including back-migrations from Eurasia, of both highly differentiated West and East Eurasian components.[6]

Africans' genetic ancestry is largely partitioned by

Overall, different African populations display genetic diversity and substructure, but can be clustered in distinct but partially overlapping groupings:[10][11][12][8][13][14]

- Khoisan or 'South African hunter-gatherers' from Southern Africa represented by the Khoisan peoples; they are associated with the deepest divergence (c. 270,000 years ago) of human genetic diversity, forming a distinct cluster of their own. They subsequently diverged into a Northern and Southern subgroup, c. 30,000 years ago.[a]

- 'Central African hunter-gatherers' or 'Rain forest hunter-gatherers' (Mbuti; associated with another deep divergence (c. 220,000 years ago). They subsequently diverged into an Eastern and Western subgroup, c. 20,000 years ago.[b]

- "Ancestral Eurasians" represent the ancestral population of modern Eurasians shortly before the Out-of-Africa expansion; they are inferred to have diverged from other African populations, most likely somewhere in Northeast Africa, c. 70,000 years ago.

- The various Neolithic Anatolian and Iranian) admixtures, with the remainder being primarily associated with Nilotic-like ancestry. They also display affinity for the Paleolithic North African Taforalt specimens of the Iberomaurusian culture.[c]

- 'Eastern African hunter-gatherers', represented by Hadza, Sandawe, Omotic-speakers, and the ancient Mota specimen; their phylogenetic relationship to other populations is not clear, but they display affinity to modern East and West African populations, and harbor Khoesan-like geneflow along a Northeast to Southwest cline, as well as later (West) Eurasian admixtures, but at lower amounts than among Afroasiatic-speakers.[d]

- "Ancient East Africans" or "Ancestral West/East Africans" associated with the common ancestor of modern Nile Valley region. They subsequently diverged at c. 18,000 years ago into the ancestors of West and West-Central African Niger-Congo and Bantu-speakers, and into the East African Nilo-Saharan/Nilotic-speakers. They represent the dominant and most widespreaded ancestry component of modern Africa, and are associated with relative recent population expansions linked to agriculture and pastoralist lifestyles. Genetic data indicates affinity for older hunter-gatherer groups in East Africa, but their exact relationship remains unclear.[10][e] There is evidence for limited geneflow (9-13%) from a human ghost lineage, referred to as 'West African foragers' with a deeper or equally deep divergence time than 'Khoisan hunter-gatherers', into modern West Africans.[16][17]

- Austronesian expansion, with the remainder ancestry being primarily associated with West-Central and East African components. The estimated date of geneflow between these sources is c. 2,200 years ago.[18]

Indigenous Africans

The term '

The

Although the validity of the Nilo-Saharan family remains controversial, the region between Chad, Sudan, and the Central African Republic is seen as a likely candidate for its homeland prior to its dispersal around 10,000–8,000 BCE.[24]

The Southern African hunter-gatherers (Khoisan) are suggested to represent the autochthonous hunter-gatherer population of southern Africa, prior to the expansion of Bantu-speakers from Western/Central Africa and East African pastoralists. Khoisan show evidence for Bantu-related admixture, ranging from nearly ~0% to up to ~87.1%.[25]

Out-of-Africa event

The "

According to Durvasula et al. (2020), there are indications that 2% to 19% (≃6.6 to 7.0%) of the DNA of West African populations may have come from an unknown archaic hominin which split from the ancestor of humans and Neanderthals between 360 kya to 1.02 mya. However, Durvasula et al. (2020) also suggests that at least part of this archaic admixture is also present in Eurasians/non-Africans, and that the admixture event or events range from 0 to 124 ka B.P, which includes the period before the Out-of-Africa migration and prior to the African/Eurasian split (thus affecting in part the common ancestors of both Africans and Eurasians/non-Africans).[32][33][34] Chen et al. (2020) found that Africans have higher Neanderthal ancestry than previously thought. 2,504 African samples from all over Africa were analyzed and tested on Neanderthal ancestry. All African samples showed evidence for minor Neanderthal ancestry, but always at lower levels than observed in Eurasians.[35]

Geneflow between Eurasian and African populations

Significant Eurasian admixture is found in

Ramsay et al. (2018) also found evidence for significant Western Eurasian admixture in various parts of Africa, from both ancient and more recent migrations, being highest among populations from Northern Africa, and some groups of the Horn of Africa:[39]

In addition to the intrinsic diversity within the continent due to population structure and isolation, migration of Eurasian populations into Africa has emerged as a critical contributor to the genetic diversity. These migrations involved the influx of different Eurasian populations at different times and to different parts of Africa. Comprehensive characterization of the details of these migrations through genetic studies on existing populations could help to explain the strong genetic differences between some geographically neighbouring populations.

This distinctive Eurasian admixture appears to have occurred over at least three time periods with ancient admixture in central west Africa (e.g., Yoruba from Nigeria) occurring between ~7.5 and 10.5 kya, older admixture in east Africa (e.g., Ethiopia) occurring between ~2.4 and 3.2 kya and more recent admixture between ~0.15 and 1.5 kya in some east African (e.g., Kenyan) populations.

Subsequent studies based on LD decay and haplotype sharing in an extensive set of African and Eurasian populations confirmed the presence of Eurasian signatures in west, east and southern Africans. In the west, in addition to Niger-Congo speakers from The Gambia and Mali, the Mossi from Burkina Faso showed the oldest Eurasian admixture event ~7 kya. In the east, these analyses inferred Eurasian admixture within the last 4000 years in Kenya.[39]

There is no definitive agreement on when or where the

Horn of Africa

While many studies conducted on Horn of Africa populations estimate a West-Eurasian admixture event around 3,000 years ago,

Madagascar

Specific East Asian-related ancestry is found among the

Northern Africa

Dobon et al. (2015) identified an autosomal ancestral component that is commonly found among modern Afroasiatic-speaking populations (as well as Nubians) in Northeast Africa. This Coptic component peaks among Copts in Sudan, which is differentiated by its lack of Arab influence, but shares common ancestry with the North African/Middle Eastern populations. It appears alongside a component that defines Nilo-Saharan speakers of southwestern Sudan and South Sudan.[67] Arauna et al. (2017), analyzing existing genetic data obtained from Northern African populations, such as Berbers, described them as a mosaic of North African (Taforalt), Middle Eastern, European (Early European Farmers), and Sub-Saharan African-related ancestries.[68]

Chen et al. (2020) analyzed 2,504 African samples from all over Africa, and found archaic Neanderthal ancestry, among all tested African samples at low frequency. They also identified a European-related (West-Eurasian) ancestry segment, which seems to largely correspond with the detected Neanderthal ancestry components. European-related admixture among Africans was estimated to be between ~0% to up to ~30%, with a peak among Northern Africans.[69] According to Chen et al. (2020), "These data are consistent with the hypothesis that back-migration contributed to the signal of Neanderthal ancestry in Africans. Furthermore, the data indicates that this back-migration came after the split of Europeans and East Asians, from a population related to the European lineage."[69]

There is a minor geneflow from North Africa in parts of Southern Europe, this is supported by the presence of an African-specific mitochondrial haplogroup among one of four 4,000 year old samples.[70] Multiple studies found also evidence for geneflow of African ancestry towards Eurasia, specifically Europe and the Middle East. The analysis of 40 different West-Eurasian populations found African admixture at a frequency of 0% to up to ~15%.[71][72][73][74]

Western Africa

Hollfelder et al. (2021) concluded that West African Yoruba people, which were previously used as "unadmixed reference population" for indigenous Africans, harbor minor levels of Neanderthal ancestry, which can be largely associated with back-migration of an "Ancestral European-like" source population.[6]

A genome-wide study of a Fulani community from Burkina Faso inferred two major admixture events in this group, dating to ~1800 ya, and 300 ya. The first admixture event took place between the West African ancestors of the Fula and ancestral North African nomadic groups. The second admixture event, relatively recent, inferred a source from Southwestern Europe, or suggests either an additional gene flow between the Fulani and Northern African groups, who carry admixture proportions from Europeans.[75] Sahelian populations like the Toubou also showed admixture coming from Eurasians.[76]

Southern Africa

Low levels of West Eurasian ancestry (European or Middle Eastern) are found in Khoe–Kwadi Khoesan-speakers. It could have been acquired indirectly by admixture with migrating pastoralists from East Africa. This hypothesis of gene flow from eastern to southern Africa is further supported by other genetic and archaeological data documenting the spread of pastoralism from East to South Africa.[77]

Regional genomic overview

North Africa

Archaic Human DNA

While

Ancient DNA

Daniel Shriner (2018), using modern populations as a reference, showed that the Natufians carried 61.2% Arabian, 21.2% Northern African, 10.9% Western Asian, and a small portion of Eastern African ancestry at 6.8%, which is associated with the modern Omotic-speaking groups found in southern Ethiopia.[47]

Egypt

Khnum-aa, Khnum-Nakht, Nakht-Ankh and JK2911 carried maternal haplogroup M1a1.[79][56]

Thuya, Tiye, Tutankhamen's mother, and Tutankhamen carried the maternal haplogroup K.[79]

JK2134 carried maternal haplogroup J1d[56] and JK2887 carried maternal haplogroup J2a1a1.[56]

JK2134 and JK2911 carried paternal haplogroup J.[56]

OM:KMM A 64 carried maternal haplogroup T2c1a.[84]

JK2888 carried paternal haplogroup

Libya

At

Morocco

Van de Loorsdrecht et al. (2018) found that of seven samples of

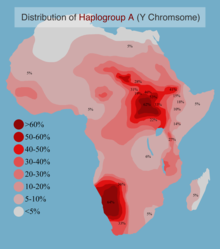

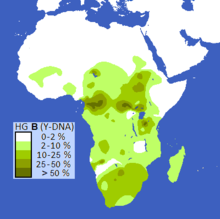

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Mitochondrial DNA

Amid the

Mitochondrial haplogroups L3, M, and N are found among

Autosomal DNA

Medical DNA

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo adaptation are regulatory DNA, and many cases of adaptation found among Africans relate to diet, physiology, and evolutionary pressures from pathogens.[90]

Lactase Persistence

West Africa

Archaic Human DNA

Archaic traits found in human fossils of

Ancient DNA

As of 2017, human ancient DNA has not been found in the region of West Africa.[92] As of 2020, human ancient DNA has not been forthcoming in the region of West Africa.[87]

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Eight male individuals from

As a result of haplogroup D0, a basal branch of haplogroup DE, being found in three

As of 19,000 years ago, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west.[95] E1b1a1-M2 likely originated in West Africa or Central Africa.[96]

Mitochondrial DNA

Around 18,000 BP, Mende people, along with Gambian peoples, grew in population size.[97]

In 15,000 BP,

Between 11,000 BP and 10,000 BP, Yoruba people and Esan people grew in population size.[97]

As early as 11,000 years ago, Sub-Saharan West Africans, bearing

Autosomal DNA

During the early period of the Holocene, in 9000 BP, Khoisan-related peoples admixed with the ancestors of the Igbo people, possibly in the western Sahara.[100][101]

Between 2000 BP and 1500 BP,

Fan et al. (2019) found that the

Medical DNA

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo

Pediculus

During the

Sickle Cell

Amid the Green Sahara, the mutation for

Schistosomes

According to Steverding (2020), while not definite: Near the

Thalassemia

Through pathways taken by

Domesticated Animal DNA

While the Niger-Congo migration may have been from West Africa into Kordofan, possibly from

Central Africa

Archaic Human DNA

Archaic traits found in human fossils of

Ancient DNA

In 4000 BP, there may have been a population that traversed from

Cameroon

Democratic Republic of Congo

At Kindoki, in the

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Haplogroup R1b-V88 is thought to have originated in Europe and migrated into Africa with farmers or herders in the Neolithic period, c. 5500 BC.[118][119][120][121] R1b-V88 is found at a high frequency among Chadic speaking peoples such as the Hausa,[76] as well as in Kanembu,[122] Fulani,[123] and Toubou[76] populations.

Mitochondrial DNA

In 150,000 BP, Africans (e.g.,

Mitochondrial

Autosomal DNA

Genetically,

Medical DNA

Evidence suggests that, when compared to other

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo

Eastern Africa

From the region of

Archaic Human DNA

While

Ancient DNA

Ethiopia

At

Kenya

At Jawuoyo Rockshelter, in

At Ol Kalou, in

At Kokurmatakore, in

At White Rock Point, in

At Nyarindi Rockshelter, in

At Lukenya Hill, in

At Hyrax Hill, in

At Molo Cave, in

At Kakapel, in

At

At

Tanzania

At Mlambalasi rockshelter, in Tanzania, an individual, dated between 20,345 BP and 17,025 BP, carried undetermined haplogroups.[139]

At Gishimangeda Cave, in

At

At Lindi, in Tanzania, an individual, dated between 1511 cal CE and 1664 cal CE, carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1a2a1a3a1d~ and L0a1a2.[138]

At Makangale Cave, on Pemba Island, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 1421 BP and 1307 BP, carried haplogroup L0a.[137]

At

Uganda

At

Y-Chromosomal DNA

As of 19,000 years ago, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west.[95]

Before the

Mitochondrial DNA

In 150,000 BP, Africans (e.g.,

Autosomal DNA

Across all areas of

Medical DNA

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo

Southern Africa

From the region of

Archaic Human DNA

While

Ancient DNA

Three

Botswana

At Nqoma, in

At Taukome, in Botswana, an individual, dated to the Early Iron Age (1100 BP), carried haplogroups E1b1a1 (E-M2, E-Z1123) and L0d3b1.[116][117]

At Xaro, in

Malawi

At Fingira rockshelter, in Malawi, an individual, dated between 6179 BP and 2341 BP, carried haplogroups B2 and L0d1.[139]

At Chencherere, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 5400 BP and 4800 BP, carried haplogroup L0k2.[137]

At Hora 1 rockshelter, in

South Africa

At Doonside, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2296 BP and 1910 BP, carried haplogroup L0d2.[142][143]

At Ballito Bay, South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 1986 BP and 1831 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2 and L0d2c1.[142][143]

At Kalemba rockshelter, in Zambia, an individual, dated between 5285 BP and 4975 BP, carried haplogroup L0d1b2b.[139]

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Various

Mitochondrial DNA

In 200,000 BP, Africans (e.g.,

Mitochondrial DNA studies also provide evidence that the San carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. This DNA is inherited only from one's mother. The most divergent (oldest) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African San groups.[144][147][148][149]

Autosomal DNA

Henn et al. (2011) found that the ǂKhomani San, as well as the

Medical DNA

Among the ancient DNA from three

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo

Recent African origin of modern humans

Between 500,000 BP and 300,000 BP,

Archaeological and fossil evidence provide support for the

In comparison to the

See also

Notes

- ^ The lineage leading to the Khoe-San is basal to all other human lineages with an estimated divergence time of 300–200 kya (e.g., the Ju|’Hoan with the lowest level of recent admixture diverged ~270 ± 12 kya).

- ^ Subsequently, the Mbuti (RHG) diverged ~220 ± 10 kya from all other human lineages, forming a second basal lineage (Schlebusch et al. 2020) (fig. 1).

- ^ First, present-day ancestry in North Africans is characterized by an autochthonous Maghrebi component related to a Paleolithic back migration to Africa from Eurasia. ... This result suggests that Iberomaurusian populations in North Africa were related to Paleolithic people in the Levant, but also that migrations of sub-Saharan African origin reached the Maghreb during the Pleistocene. ... This result is consistent with our previous finding that Cushitic ancestry formed by admixture between Nilo-Saharan and Arabian ancestries39. ... While these findings show that a Levant-Neolithic-related population made a critical contribution to the ancestry of present-day eastern Africans (Lazaridis et al., 2016), present-day Cushitic speakers such as the Somali cannot be fit simply as having Tanzania_Luxmanda_3100BP ancestry. The best fitting model for the Somali includes Tanzania_Luxmanda_3100BP ancestry, Dinka-related ancestry, and 16% ± 3% Iranian-Neolithic-related ancestry (p = 0.015). This suggests that ancestry related to the Iranian Neolithic appeared in eastern Africa after earlier gene flow related to Levant Neolithic populations, a scenario that is made more plausible by the genetic evidence of admixture of Iranian-Neolithic-related ancestry throughout the Levant by the time of the Bronze Age (Lazaridis et al., 2016) and in ancient Egypt by the Iron Age (Schuenemann et al., 2017).

- ^ This could either suggest deep population structure with EAHG and southern hunter–gatherer groups tracing some of their ancestries to a basal central African RHG lineage (Lipson et al. 2020, 2022) or gene flow between southern African and central African foragers, as indicated by a distinct allele-sharing pattern between the !Xun/Ju|’Hoan and Mbuti (Scheinfeldt et al. 2019; Bergström et al. 2020; Schlebusch et al. 2020). ... Currently, insufficient data exist to estimate the (even older) Eastern African-Omotic divergence time.

- ^ For the pair of Western and West-Central African ancestries, the point estimate of divergence time was 6,900 years ago. ... Western Africa ancestry is the predominant ancestry among populations from the area around Senegal and the Gambia whereas West-Central African ancestry predominates among populations from the area around Nigeria. ... Comparing two Mandenka and one Gambian to two Esan and one Yoruba, the split time was estimated to be <4,600 years ago, which is expected to be an underestimate compared to the FST-based time because of the presence of 0–11.1% West-Central African ancestry in the Western Africans and 26.7–35.0% Western African ancestry in the West-Central Africans. ... In turn, Eastern African ancestry, which is characteristic of modern Nilotes, and the common ancestor of Western and West-Central African ancestries derived from a common ancestor 18,000 years ago based on decomposition of FST or <13,800 years ago based on msmc analysis of two Dinka compared to either one Gambian and one Mandenka or two Esan. The latter time is relatively underestimated because of the presence of 22.6–26.1% Western or West-Central African ancestry in the Eastern Africans. This common ancestor probably existed in the Nile Valley. ... Currently, insufficient data exist to estimate the (even older) Eastern African-Omotic divergence time.

References

- S2CID 10418009.

- S2CID 131383927.

- S2CID 134694090.

- ISBN 978-0-19-993536-9.

- S2CID 224855920.

- ^ PMID 33438014.

- PMID 31023338.

- ^ PMID 28484253.

- ^ "A great African gene migration". cosmosmagazine.com. 29 October 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Ananyo Choudhury, Shaun Aron, Dhriti Sengupta, Scott Hazelhurst, Michèle Ramsay (1 August 2018). "African genetic diversity provides novel insights into evolutionary history and local adaptations". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- PMID 36987563.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 31023338.

- PMID 28938123.

- ^ S2CID 219974966.

- ^ PMID 28484253.

- PMID 28938123.

- PMID 31969706.

The West African clade is distinguished by admixture from a deep source that can be modeled as a combination of modern human and archaic ancestry. The modern human component diverges at almost the same point as Central and southern African hunter-gatherers and is tentatively related to the deep source contributing ancestry to Mota, while the archaic component diverges close to the split between Neanderthals and modern humans (Supplementary Information section 3).

- PMID 27188237.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0465-5.

- PMID 22927824.

- S2CID 54923700.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0465-5.

- ^ Blench R (September 2016). Can we visit the graves of the first Niger-Congo speakers? (PDF). 2nd International Congress: Towards Proto-Niger-Congo: Comparison and Reconstruction. Paris.

- ISBN 978-0-19-960989-5.

- PMID 31288264.

- ^ S2CID 206666517.

- PMID 27127403.

- PMID 30007846.

- ^ "One Species, Many Origins". www.shh.mpg.de. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Vallini L, et al. (7 April 2022). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- PMID 32666166.

- PMID 32095519. "Non-African populations (Han Chinese in Beijing and Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry) also show analogous patterns in the CSFS, suggesting that a component of archaic ancestry was shared before the split of African and non-African populations...One interpretation of the recent time of introgression that we document is that archaic forms persisted in Africa until fairly recently. Alternately, the archaic population could have introgressed earlier into a modern human population, which then subsequently interbred with the ancestors of the populations that we have analyzed here. The models that we have explored here are not mutually exclusive, and it is plausible that the history of African populations includes genetic contributions from multiple divergent populations, as evidenced by the large effective population size associated with the introgressing archaic population...Given the uncertainty in our estimates of the time of introgression, we wondered whether jointly analyzing the CSFS from both the CEU (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry) and YRI genomes could provide additional resolution. Under model C, we simulated introgression before and after the split between African and non-African populations and observed qualitative differences between the two models in the high-frequency–derived allele bins of the CSFS in African and non-African populations (fig. S40). Using ABC to jointly fit the high-frequency–derived allele bins of the CSFS in CEU and YRI (defined as greater than 50% frequency), we find that the lower limit on the 95% credible interval of the introgression time is older than the simulated split between CEU and YRI (2800 versus 2155 generations B.P.), indicating that at least part of the archaic lineages seen in the YRI are also shared with the CEU..."

- ^ [1] Archived 7 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine Supplementary Materials for Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations", section "S8.2" "We simulated data using the same priors in Section S5.2, but computed the spectrum for both YRI [West African Yoruba] and CEU [a population of European origin] . We found that the best fitting parameters were an archaic split time of 27,000 generations ago (95% HPD: 26,000-28,000), admixture fraction of 0.09 (95% HPD: 0.04-0.17), admixture time of 3,000 generations ago (95% HPD: 2,800-3,400), and an effective population size of 19,700 individuals (95% HPD: 19,300-20,200). We find that the lower bound of the admixture time is further back than the simulated split between CEU and YRI (2155 generations ago), providing some evidence in favor of a pre-Out-of-Africa event. This model suggests that many populations outside of Africa should also contain haplotypes from this introgression event, though detection is difficult because many methods use unadmixed outgroups to detect introgressed haplotypes [Browning et al., 2018, Skov et al., 2018, Durvasula and Sankararaman, 2019] (5, 53, 22). It is also possible that some of these haplotypes were lost during the Out-of-Africa bottleneck."

- PMID 32095519.

- S2CID 210955842.

- PMID 27324836.

- S2CID 204972040.

- ^ PMID 24550290.

- ^ PMID 29741686.

- ISBN 978-0-262-54218-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-02227-9.

- OCLC 852516752.

- ^ PMID 24921250.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2.

- ^ S2CID 162986221– via JSTOR.

- ISBN 978-1-134-81623-1.

- ^ PMID 30079081.

and a sub-Saharan African component in Natufians that localizes to present-day southern Ethiopia.

- S2CID 9441236.

- PMID 33864377.

- S2CID 8057990.

- S2CID 162986221.

- ISBN 978-0-12-765490-4, retrieved 29 March 2022

- S2CID 19155657.

- ISBN 978-0-520-04574-3.

- S2CID 13350469.

- ^ PMID 28556824.

- PMID 31827175.

- PMID 27146119.

- PMID 26912899.

- PMID 34117245.

- S2CID 21753825.

- PMID 15288523.

- PMID 24395773.

- ^ PMID 27188237.

- ^ PMID 33481023.

- ^ Nicolas B, et al. (4 February 2019). "Evidence of Austronesian Genetic Lineages in East Africa and South Arabia: Complex Dispersal from Madagascar and Southeast Asia". Genome Biology and Evolution, Volume 11, Issue 3.

- PMID 26017457.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2

- ^ S2CID 210955842.

- PMID 30963949.

- PMID 21533020.

- PMID 23733930.

- PMID 19218534.

- S2CID 34837532.

- PMID 33105478.

- ^ S2CID 38169172.

- PMID 25461616.

- ^ S2CID 231883210.

- ^ PMID 33059357.

- PMID 29494531.

- S2CID 206896841.

- ^ Gourdine JP, Keita S, Gourdine JL, Anselin A. "Ancient Egyptian Genomes from northern Egypt: Further discussion". Nature Communications.

- ^ "Shocking truth behind Takabuti's death revealed". Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ PMID 31945091.

- PMID 30837540.

- ^ S2CID 206666517.

- ^ S2CID 226555687.

- ^ S2CID 251653686.

- ^ Osman MM, Hassan HY, Elnour MA, Makkan H, Gebremeskel EI, Gais T, et al. "Mitochondrial HVRI and whole mitogenome sequence variations portray similar scenarios on the genetic structure and ancestry of northeast Africans" (PDF). Meta Gene. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ S2CID 257803764.

- ^ S2CID 221179656.

- S2CID 133758803.

- S2CID 11190055.

- S2CID 189817793.

- ^ PMID 29526279.

- PMID 26108492.

- ^ S2CID 52289534.

- S2CID 27594333.

- S2CID 24672148.

- S2CID 6885967.

- S2CID 4463627.

- S2CID 226039427.

- S2CID 257834341.

- PMID 31023338.

- S2CID 257286226.

- ^ S2CID 257458855.

- S2CID 14033603.

- ^ PMID 33461216.

- PMID 30827499.

- ^ S2CID 216082225.

- ^ PMID 32862777.

- S2CID 46000591.

- S2CID 54463512.

- S2CID 104296971.

- S2CID 210862788.

- ^ PMID 32582847.

- ^ PMID 32582847.

- PMID 29433568.

R1b-V88 topology indicates a Europe-to-Africa migration. Indeed, our data suggest a European origin of R1b-V88 about 12.3 kya.

- PMID 32094358.

Two very basal R1b-V88 (with several markers still in the ancestral state) appear in Serbian hunter-gatherers as old as 9,000 BCE, which supports a Mesolithic origin of the R1b-V88 clade in or near this broad region. The haplotype appears to have become associated with the Mediterranean Neolithic expansion … it is found in an individual buried at the Els Trocs site in the Pyrenees (modern Aragon, Spain), dated 5,178-5,066 BC and in eleven ancient Sardinians of our sample. Interestingly, markers of the R1b-V88 subclade R1b-V2197, which is at present day found in most African R1b-V88 carriers, are derived only in the Els Trocs individual and two ancient Sardinian individuals. This configuration suggests that the V88 branch first appeared in eastern Europe, mixed into Early European farmer (EEF) individuals (after putatively sex-biased admixture), and then spread with EEF to the western Mediterranean. … A west Eurasian R1b-V88 origin is further supported by a recent phylogenetic analysis that puts modern Sardinian carrier haplotypes basal to the African R1b-V88 haplotypes. The putative coalescence times between the Sardinian and African branches inferred there fall into the Neolithic Subpluvial ("green Sahara", about 7,000 to 3,000 years BCE). Previous observations of autosomal traces of Holocene admixture with Eurasians for several Chadic populations (Haber et al. 2016) provide further support for a hypothesis that at least some amounts of EEF ancestry crossed the Sahara southwards.

- PMID 31744094.

The recent and detailed reconstruction of the phylogeny of the R1b-V88 haplogroup has revealed that the rare European R1b-V88 lineages (R1b-M18 and R1b-V35) originated from the root of the phylogeny much earlier (about 12.34 kya) than the separation of the African lineages (7.85 ± 0.90 kya), thus supporting an origin of R1b-V88 outside Africa and a subsequent diffusion in sub-Saharan Africa through the Last Green Sahara period during the Middle-Holocene. Interestingly, recent studies on ancient DNA identified the most ancient R1b-V88 samples (dated 11 and 9 ky) in East Europe (Serbia and Ukraine, respectively) and more recent R1b-V88 samples (dated 7 and 6 ky) in Spain and Germany, thus supporting a European origin

- PMID 38200295.

Newly reported samples belonging to haplogroup R1b were distributed between two distinct groups depending on whether they formed part of the major European subclade R1b1a1b (R1b-M269). Individuals placed outside this subclade were predominantly from Eastern European Mesolithic and Neolithic contexts, and formed part of rare early diverging R1b lineages. Two Ukrainian individuals belonged to a subclade of R1b1b (R1b-V88) found among present-day Central and North Africans, lending further support to an ancient Eastern European origin for this clade.

- PMID 30259956.

- PMID 28736914.

- ^ PMID 18216239.

- ^ Sarah A. Tishkoff et al. 2007, History of Click-Speaking Populations of Africa Inferred from mtDNA and Y Chromosome Genetic Variation. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2007 24(10):2180-2195

- ^ Lluis Quintana-Murci et al. MtDNA diversity in Central Africa: from hunter-gathering to agriculturalism. CNRS-Institut Pasteur, Paris

- PMID 26211407.

- PMID 22570615.

- PMID 19924308.

- PMID 19541519.

- S2CID 25743789.

- S2CID 25743789.

- PMID 33547782.

- PMID 22726845.

- ^ PMID 31147405.

- ^ PMID 31147405.

- ^ PMID 28938123.

- ^ S2CID 250534036.

- ^ S2CID 247083477.

- ^ Neves da Nova Fernandes VC. "High-resolution characterization of genetic markers in the Arabian Peninsula and Near East" (PDF). White Rose eTheses Online. University of Leeds.

- ^ PMID 33367711.

- ^ S2CID 206663925.

- ^ S2CID 206663925.

- ^ S2CID 52862939.

- PMID 11420360.

- PMID 21092339.

- PMID 10739760.

- PMID 17656633.

- S2CID 19515426.

- PMID 21383195.

- Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ PMID 32863518.

- S2CID 231587564.

- ^ PMID 33408383.

- ^ OCLC 1013546425.