Mongol campaign against the Nizaris

| Mongol campaign against the Nizaris | |

|---|---|

| Part of the | |

| Result | Mongol victory |

Supported by the local dynasties of Anatolia Tabaristan Fars Iraq Azerbaijan Arran Shirvan Georgia

Armenia- Möngke Khan

- Hülegü

- Kitbuqa

Tegüder

Tegüder Buqa Temür

Buqa Temür- Köke Ilgei

- Guo Kan

- Quli

- Balagha

- Tutar

- Abaqa

- Yoshmut

- Arghun Aqa

- Büri †

Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad

Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad Muhtasham Nasir al-Din ibn Abi Mansur

Muhtasham Nasir al-Din ibn Abi Mansur

Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah

Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah

Vizier Shams al-Din Gilaki

Vizier Shams al-Din Gilaki

Khwaja Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Khwaja Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muqaddam al-Din

Muqaddam al-Din

Qadi Tajuddin Mardanshah

Qadi Tajuddin Mardanshah

250,000

- 1,000 squads of Chinese and Muslim siege engineers

The Mongol campaign against the Nizaris of the Alamut period (the

Hülegü's campaign began with attacks on strongholds in Quhistan and Qumis amidst intensified internal dissensions among Nizari leaders under Imam Muhammad III of Alamut whose policy was fighting against the Mongols. His successor, Rukn al-Din Khurshah, began a long series of negotiations in face of the implacable Mongol advance. In 1256, the Imam capitulated while besieged in Maymun-Diz and ordered his followers to do likewise according to his agreement with Hülegü. Despite being difficult to capture, Alamut ceased hostilities too and was dismantled. The Nizari state was thus disestablished, although several individual forts, notably Lambsar, Gerdkuh, and those in Syria continued to resist. Möngke Khan later ordered a general massacre of all Nizaris, including Khurshah and his family.

Many of the surviving Nizaris scattered throughout Western, Central, and South Asia. Little is known about them afterward, but their communities maintain some sort of independence in their heartland of Daylam and their Imamate reappeared later in Anjudan.

Sources

The main primary source is the

Background

The

In 1192 or 1193,

Early Nizari–Mongol relations

In 1221, the Nizari Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan sent emissaries to Genghis Khan in Balkh. The Imam died in the same year and was succeeded by his 9-years-old son, Ala al-Din Muhammad.[5]

After the fall of the

The Nizari Imam sought anti-Mongol alliances as far as

In 1246, the Nizari Imam, together with the new Abbasid caliph Al-Musta'sim and many Muslim rulers, sent a diplomatic mission under the Nizari muhtashams (governors) of Quhistan, Shihab al-Din and Shams al-Din, to Mongolia on the occasion of the enthronement of the new Mongol Great Khan, Güyük Khan. But the latter dismissed them, and soon dispatched reinforcements under Eljigidei to Persia, instructing him to dedicate one-fifth of the forces there to reduce rebellious territories, beginning with the Nizari state. Güyük himself had intended to participate but died shortly afterward.[3] A Mongol noyan (commander), Chagatai the Elder, was reportedly assassinated by the Nizaris around this time.[7]

Güyük's successor,

Hülegü's campaign

Campaign against Quhistan, Qumis, and Khurasan

In March 1253,

In October 1253, Hülegü left his orda in Mongolia and began his march with a tümen at a leisurely pace and increased his number in his way.[15][20][16] He was accompanied by two of his ten sons, Abaqa and Yoshmut,[19] his brother Subedei, who died en route,[21] his wives Öljei and Yisut, and his stepmother Doquz.[19][22]

In July 1253, Kitbuqa who had been in Quhistan, pillaged, slaughtered, and seized probably temporarily Tun (Ferdows) and Turshiz. A few months later, Mehrin and several other castles in Qumis fell as well.[18] In December 1253, Girdkuh's garrison audaciously sallied at night and killed a hundred Mongols, including Büri.[18][16] Gerdkuh was on the verge of falling due to an outbreak of cholera, but unlike Lambsar, it survived the epidemic and was saved by the arrival of reinforcements from Alamut sent by the Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad in the summer of 1254. The impregnable fort resisted for many years (see below).[16][18][23]

In September 1255, Hülegü arrived near

The inexorable Mongol advances in Quhistan caused consternation among the Nizari leadership. The relationship had already deteriorated between Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad, who was reportedly afflicted by melancholia, and his advisors and Nizari leaders, as well as with his son Rukn al-Din Khurshah, the designated future Imam. According to Persian historians, the Nizari elites had planned a "coup" against Muhammad in order to replace him with Khurshah who would subsequently enter into immediate negotiations with the Mongols, but Khurshah fell ill before implementing this plan.[18] Nevertheless, on December 1 or 2, 1255, Muhammad died under suspicious circumstances and was succeeded by Khurshah[18][16] who was in his late twenties.[1]

To reach Iran, Hülegü had entered via the Chaghatai khaganate, crossing the Oxus (Amu Darya) in January 1256 and entered Quhistan in April 1256. Hülegü chose Tun, which had not been reduced effectively by Kitbuqa, as his first target. An obscure incident occurred while Hülegü was passing through the Zawa and Khwaf districts which deterred him from supervising the campaign. He instructed Kitbuqa and Köke Ilgei in May 1256 to attack Tun again, which was sacked after a week-long siege, and almost all its inhabitants were massacred. The Mongol commanders then regrouped with Hülegü and attacked Tus.[20][16]

Campaign against Rudbar and Alamut

As soon as he had been in power, Khurshah announced the Nizari leadership's willingness to submit to the Mongol rule to the nearest Mongol commander, noyan Yasur in Qazvin. Yasur replied that the Imam personally should visit Hülegü's camp. Skrimishes are recorded between Yasur and the Nizaris of Rudbar: on June 12, he was defeated in a battle on Mount Siyalan near Alamut, where the Nizari forces had been mustered, but managed to harass the Nizaris of the region.[25][26]

As Hülegü reached

The Mongols campaigned against the Nizari heartland of Alamut and Rudbar from three directions. The right wing, under Buqa Temür and Köke Ilgei, marched via Tabaristan. The left wing, under Tegüder and Kitbuqa, marched via Khuwar and Semnan. The center was under Hulegu himself. Meanwhile, Hülegü sent another warning to Khurshah. Khurshah was at the Maymun-Diz fortress and was apparently playing for time; by resisting longer, the arrival of winter could have stopped the Mongol campaigning. He sent his vizier Kayqubad; they met the Mongols in Firuzkuh and offered the surrender of all strongholds except Alamut and Lambsar, and again asked for a year's delay for Khurshah to visit Hülegü in person. Meanwhile, Khurshah ordered Gerdkuh and the fortresses of Quhistan to surrender, which their chiefs did, but the garrison of Gerdkuh continued to resist. The Mongols continued to advance and reached Lar, Damavand, and Shahdiz. Khurshah sent his 7- or 8-years-old son as a show of good faith, but he was sent back due to his young age. Khurshah then sent his second brother Shahanshah (Shahin Shah), who met the Mongols at Rey. But Hülegü demanded the dismantling of the Nizari fortifications to show his goodwill.[16][28][29][1]

Numerous negotiations between the Nizari Imam and Hülegü were futile. Apparently, the Nizari Imam sought to at least keep the main Nizari strongholds, while the Mongols were adamant that the Nizaris must fully submit.[4]

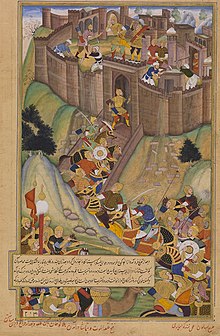

Siege of Maymun-Diz

On 8 November 1256, Hülegü set up camp on a hilltop facing Maymun-Diz and encircled the fortress with his forces by marching over the Alamut mountains via the Taleqan valley and appearing at the foot of Maymun-Diz.[16]

Maymun-Diz could have been attacked by mangonels; that was not the case with Alamut, Nevisar Shah, Lambsar and Gerdkuh, all of which were on top of high peaks. Nevertheless, the strength of the fortification impressed the Mongols, who surveyed it from various angles to find a weak point. Since the winter was approaching, Hülegü was advised by the majority of his lieutenants to postpone the siege, but he decided to proceed. Preliminary bombardments were performed for three days by mangonels from a nearby hilltop with casualties on both sides. A direct Mongol assault on the fourth day was repulsed. The Mongols then used heavier siege engines hurling javelins dipped in burning pitch and set up additional mangonels all around the fortifications.[16]

Later that month, Kuhrshah sent a message offering his surrender on the condition of the immunity of him and his family. Hülegü's royal decree was sent by Ata-Malik Juvayni, who took it personally to Khurshah, asking for his signature, but Khurshah was hesitant. After several days, Hülegü began another bombardment and on 19 November, Khurshah and his entourage descended from the fortress and surrendered. The evacuation of the fortress continued until the next day. A small part of the garrison refused to surrender and fought in a last stand in a high domed building in the fortress; they were defeated and slaughtered after three days. [16][28][30]

The Nizari leadership's decision to surrender was apparently influenced by outside scholars such as al-Tusi.[31]

An inexplicable aspect of the events for historians is why Alamut made no effort to assist their besieged comrades in Maymun-Diz.[32]

Capitulation of Alamut

Khurshah instructed all Nizari castles of the Rusbar valley to capitulate, evacuate, and dismantle their forts. All castles (around forty) subsequently capitulated, except

Juvayni describes the difficulty by which the Mongols dismantled the plastered walls and lead-covered ramparts of Alamut. The Mongols had to set fire to the buildings and then destroy them piece by piece. He also notes the extensive chambers, galleries, and deep tanks, replete with wine, vinegar, honey, and other goods. During the pillage, one man was almost drowned in a honey store.[16]

After examining Alamut's famous library, Juvayni saved "copies of the Qur'an and other choice books" as well as "astronomical instruments such as kursis (part of an

Juvayni noted the impregnability and self-sufficiency of Alamut and the other Nizari fortresses. Rashid al-Din similarly writes of the good fortune of Mongols in their war against the Nizaris.[31]

Massacres of the Nizaris and aftermath

By 1256, Hülegü almost eliminated the Persian Nizaris as an independent military force.

Hülegü then moved with the bulk of his army to Azerbaijan, officially established his own khanate (the

As the centralized government of the Nizaris was disestablished, the Nizaris either were killed or had abandoned their traditional strongholds. Many of them migrated to

Resistance by the Nizaris in Persia was still ongoing in some forts, notably

In 1275, a Nizari force under a son of Khurshah (titled Naw Dawlat or Abu Dawlat), where they are recorded to be active in the 14–15th century.

References

- ^ JSTOR 3217688.

- ISBN 978-1-4092-0863-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- ^ a b c d e Daftary, Farhad. "The Mediaeval Ismailis of the Iranian Lands | The Institute of Ismaili Studies". www.iis.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6164-0.

- ^ B. Hourcade, “Alamüt,” Encyclopædia Iranica, I/8, pp. 797–801; an updated version is available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alamut-valley-alborz-northeast-of-qazvin- (accessed on 17 May 2014).

- ISBN 978-0-86078-002-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-297-86333-5.

- ISBN 978-1-78346-150-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4711-5664-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-5772-1.

- ^ "Magiran | روزنامه ایران (1392/07/02): ناگفته هایی از عظیم ترین دژ فردوس". www.magiran.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Magiran | روزنامه شرق (1390/01/15) : قلعه ای در دل کوه فردوس". www.magiran.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-474-1857-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- ^ a b c 霍渥斯 (1888). History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century ... 文殿閣書莊. pp. 95–97.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-21635-8.

- ISBN 978-1-108-42489-9.

- ISBN 978-0500973554.

- ISBN 978-0-7185-1180-7.

- ^ "Tarkikh – E – Imamat". www.ismaili.net.

- Jami' al-Tawarikh

- ISBN 978-0-415-96692-4.

- ^ ISBN 9781605201351.

- ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- ISBN 978-1-86019-407-8.

- ^ a b c "Il-Khanidas i. Dynastic History – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-84725-146-6.

- ^ Franzius, Enno (1969). History of the Order of Assassins. [Illustr.] Funk & Wagnalls. p. 138.

- ^ Bretschneider, E. (1910). Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: pt. 3. Explanation of a Mongol-Chinese mediæval map of central and western Asia. pt. 4 Chinese intercourse with the countries of central and western Asia during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company, Limited. p. 110.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-531173-0.

- ISBN 978-1-139-46578-6.

- ISBN 978-1-59477-873-5.

- ISBN 978-0-19-804259-4.

Further reading

- Dashdondog, Bayarsaikhan (2020). "Mongol Diplomacy of the Alamut Period". Eurasian Studies. 17 (2): 310–326. S2CID 219012875.