Mongol invasion of Java

| Mongol invasion of Java | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions and conquests and Kublai Khan's campaigns | ||||||||||

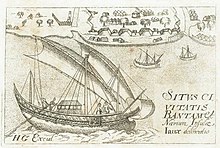

Mongol invasion of Java in 1293 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

Yuan dynasty |

Kediri Kingdom |

Majapahit Empire (since 26 May) | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

|

20,000[6]–30,000[7] 500–1,000 ships | 10,000[8][9][a][b]–100,000+[c] |

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

|

5,000 dead[12][13] >100 ships captured |

| ||||||||

The

Background

According to the

Meanwhile, after defeating

The Kediri (Gelang-gelang) army attacked Singhasari simultaneously from both the north and south flanks. The king of Singhasari only noticed the invasion from the north and sent his son-in-law, Nararya Sanggramawijaya (Raden Wijaya), northward to vanquish the rebellion. The northern attack was quashed, but the southern attack under the command of Kebo Mundarang successfully remained undetected until it reached and sacked the unprepared capital city of Kutaraja.[23] Jayakatwang usurped and killed Kertanegara during the Tantra sacred ceremony while drinking palm wine, thus bringing an end to the Singhasari Kingdom.[24] The death of Kertanegara and the fall of Singhasari is recorded in the Gajah Mada inscription in the month of Jyesta in 1214 Saka, which has been interpreted as April–May 1292 or between 18th May and the 15th June of 1292.[25]

Having learned of the fall of the

Military composition

There were 5,000 men commanded by Shi Bi, 2,000 from the garrison in

The History of Yuan recorded that the Javanese army had more than 100,000 men. This is now believed to be an exaggerated or mistaken number. Modern estimates place the Javanese forces at around the same size as the Yuan army, of around 20,000 to 30,000 men.[8][9][note 3] According to a Chinese record, Java already had a standing army, an achievement that only a handful of Southeast Asian empires could hope to achieve. This army numbered around 30,000 men that were paid in gold, recorded as early as 1225 in Zhu Fan Zhi.[9][34][35]: 467

Military forces in various parts of Southeast Asia were lightly armored. As was common in Southeast Asia, most of the Javanese forces were composed of temporarily conscripted commoners (

Invasion

The order to subdue

When the

On the 22nd March, all of the troops gathered in Kali Mas. At the headwaters of the river was the palace of the Tumapel (Singhasari) king. This river was the entryway to Java, and here they decided to battle. A Javanese minister blocked the river using boats. The Yuan commanders then made a crescent-shaped encampment at the bank of the river. They instructed the waterborne troops, cavalry, and infantry to move forward together. The minister abandoned his boats and fled in the night. More than 100 large boats with a devil head at the bow were seized by Yuan forces.[48][46]

A large portion of the army was tasked to guard the estuary of Kali Mas; meanwhile, the main troops advanced. Raden Wijaya's messenger said that the king of Kediri had chased him to Majapahit and begged the Yuan army to protect him. Because the position of Kediri's army couldn't be determined, the Yuan army returned to Kali Mas. Upon hearing information from Yighmish that the enemy's army would arrive that night, the Yuan army departed to Majapahit.[48][13]

On the 14th April, Kediri's army arrived from 3 directions to attack Wijaya. In the morning of the 15th April, Yighmish led his troops to attack the enemy in the southwest, but couldn't find them. Gao Xing battled the enemy in the southeast, eventually forcing them to flee into the mountains. Near midday, enemy troops came from the southeast. Gao Xing attacked again and managed to defeat them in the evening.[48][13]

On the 22nd April, the troops split into 3 to attack Kediri, and it was agreed that on the 26th April they would meet up in Daha to begin the attack after hearing cannon fire. The first troops sailed along the river. The second troops led by Yighmish marched along the eastern riverbank while the third army led by Gao Xing marched along the western riverbank. Raden Wijaya and his troops marched in the rear.[49][13]

Battle of the Brantas

The army arrived at Daha on the 26th April. The prince of

Once Jayakatwang had been captured by Yuan forces, Raden Wijaya returned to Majapahit, ostensibly to prepare his tribute settlement, and leaving his allies to celebrate their victory. Shi Bi and Yighmish allowed Raden Wijaya to go back to his country to prepare his tribute and a new letter of submission, but Gao Xing disliked the idea and he warned the other two.[13] Wijaya asked the Yuan forces to come to his country unarmed, as the princesses could not stand the sight of weapons.[53][54]

Two hundred unarmed Yuan soldiers led by two officers were sent to Raden Wijaya's country, but on the 26th May Raden Wijaya quickly mobilized his forces again and ambushed the Yuan convoy. After that Raden Wijaya marched his forces to the main Yuan camp and launched a surprise attack, killing many and sending the rest running back to their ships. Shi Bi was left behind and cut off from the rest of his army, and was obliged to fight his way eastward through 123 km of hostile territory.[note 7] Raden Wijaya did not engage the Mongols head-on; instead, he used all possible tactics to harass and reduce the enemy army bit by bit.[55] During the rout, the Yuan army lost a part of the spoils that had been captured beforehand.[56][57]

The Yuan forces had to withdraw in confusion, as the monsoon winds to carry them home would soon end, leaving them to wait on a hostile island for six months. Jayakatwang composed Kidung Wukir Polaman during captivity in Jung Galuh,[58] but the Mongols killed him and his son before they departed.[59] They sailed back on the 31st May to Quanzhou in 68 days.[60] The Kudadu inscription hints at a battle between the Javanese fleet commanded by rakryan mantri Arya Adikara[note 8] and the Mongol-Chinese fleet.[62] Kidung Panji Wijayakrama indicated that Mongol ships were either destroyed or captured.[63] Shi Bi's troops lost more than 3,000 soldiers.[64] Modern research by Nugroho estimated 60% of the Yuan army was killed[11] (with total losses of 12,000–18,000 soldiers), with an unknown number of soldiers taken prisoner and an unknown number of ships destroyed or captured.[40][65] In early August 1293, the army arrived in China. They brought Jayakatwang's children and some of his officers, numbering more than 100. They also acquired the nation's map, population registration, and a letter with golden writings from the king of Muli/Buli (probably Bali). They captured loot in form of valuables, incenses, perfumes, and textiles; all are counted to be worth more than 500,000 taels of silver.[60]

Aftermath

- Yuan dynasty bronze hand cannon, Xi'an, China.

- Bronze hand cannon cetbang, found in the Brantas river, Jombang.

The three Yuan generals, demoralized by the considerable loss of their elite soldiers due to the ambush, returned to their empire with the surviving soldiers. Upon their arrival, Shi Bi was condemned to receive seventy lashes and have a third of his property confiscated for allowing the catastrophe. Yighmish also was reprimanded and a third of his property was confiscated. But Gao Xing was awarded 50 taels of gold for protecting the soldiers from a total disaster. Later, Shi Bi and Yighmish were shown mercy, and the emperor restored their reputation and property.[66]

This failure was the last expedition in Kublai Khan's reign. Majapahit, in contrast, became the most powerful state of its era in the region.[67] Kublai Khan summoned his minister, Liu Guojie, to prepare another invasion of Java with a 100,000-strong army, but this plan was canceled after his death.[68] Travelers passing the region, such as Ibn Battuta and Odoric of Pordenone, however, noted that Java had been unsuccessfully attacked by the Mongols several times.[69]: 885 [70][71] The Gunung Butak inscription from 1294 may have mentioned that Arya Adikara intercepted a further Mongol invasion and defeated it before landing in Java.[62]

This invasion may have involved the first use of gunpowder in the

Legacy

The Mongols left two inscriptions on the Serutu Island on February 25, 1293. The inscriptions were called the Pasir Kapal and the Pasir Cina inscriptions.[77]

See also

- Mongol invasions of Vietnam

- Mongol invasions of Japan

- Cetbang, Majapahit gunpowder powder whose technology was obtained from this incursion

- Bedil, a term for gunpowder-based weapon of the region

Notes

- ^ According to Pararaton, Kebo Mundarang battled in the east. He was pursued by Rangga Lawe to a place called Trinipanti valley and killed.[4] And according to another source, Kebo Mundarang battled in the south. He was brought to a plain and executed by Ken Sora.[5]

- ^ According to Pararaton, Panglet was killed by Ken Sora.

- ^ According to Kidung Harsawijaya, during the attack on Singhasari, the Daha troops who attacked from the south numbered 10,000 men; while the northern troops were unspecified. The Singhasari troops that attacked Malayu and later sided with Wijaya before the foundation of the Majapahit settlement also numbered 10,000. This points to a probable number of 20,000; not including the number of those killed during the fall of Singhasari and the Pamalayu expedition and the number of new troops who came from Madura under Arya Wiraraja.[10]

- ^ The dates in this article are taken from Lo 2012, pp. 303–308 and Hung et al. 2022, p. 7.

- ^ From the south according to Kidung Panji Wijayakrama, or east according to Pararaton.[50] Nevertheless Kidung Panji Wijayakrama indicated there is a clash in the east too.[51]

- ^ According to Pararaton, Kebo Mundarang battled in the east. He was pursued by Rangga Lawe to a place called Trinipanti valley and killed.[4]

- ^ The distance is written as 300 li in the Account of Shi Bi, History of the Yuan dynasty book 162. See Groeneveldt 1876, p. 27.

- ^ An alternate name of Banyak Wide, also known as Arya Wiraraja.[61]

- ^ According to Kidung Harsawijaya, during the attack on Singhasari, the Daha troops who attacked from the south numbered 10,000 men; while the northern troops were unspecified.[10]

- ^ modern estimate

- ^ Mongol claim

- ^ According to Kidung Harsawijaya, the Singhasari troops that attacked Malayu and later sided with Wijaya before the foundation of the Majapahit settlement also numbered 10,000. This points to a probable number of 20,000; not including the number of those killed during the fall of Singhasari and the Pamalayu expedition and the number of new troops who came from Madura under Arya Wiraraja.[10]

References

- ^ Hung et al. 2022, p. 7.

- ISBN 978-90-04-06196-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ a b Bade 2013, p. 50, 188, 258.

- ^ a b Bade 2013, p. 188, 227–228.

- ISBN 0-609-80964-4

- ^ a b Bade 2013, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Poesponegoro & Notosusanto 2019, p. 452.

- ^ a b c d Miksic 2013, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Bade 2013, p. 235, 237.

- ^ a b Nugroho 2011, p. 119.

- ^ a b Nugroho 2011, p. 115, 118.

- ^ a b c d e f Groeneveldt 1876, p. 24.

- ISBN 0-609-80964-4

- ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Groeneveldt 1876, p. 30.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 106–107.

- ^ Hung et al. 2022, p. 4–5.

- ^ Weatherford (2004), and also Man (2007).

- ^ George Coedès. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia.

- ISBN 9780824803681.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 33, 233, 249–250.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 221.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 250–251, 254.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 44, 130, 186.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 187–188, 224, 230–231, 256–257.

- ^ Groeneveldt 1876, p. 21.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 255, 274.

- ^ Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". T'oung Pao. 3: 1–11.

- ^ a b Bade 2013, p. 46.

- ^ Bowring 2019, p. 129.

- ^ Worcester, G. R. G. (1947). The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze, A Study in Chinese Nautical Research, Volume I: Introduction; and Craft of the Estuary and Shanghai Area. Shanghai: Order of the Inspector General of Customs.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Yang, Shao-yun (15 June 2020). "A Chinese Gazetteer of Foreign Lands: A new translation of Part 1 of the Zhufan zhi 諸蕃志 (1225)". Storymaps. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Miksic, John N.; Goh, Geok Yian (2017). Ancient Southeast Asia. London: Routledge.

- ^ Oktorino, Nino (2020). Hikayat Majapahit - Kebangkitan dan Keruntuhan Kerajaan Terbesar di Nusantara. Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo. p. 111–113.

- ^ Jákl 2014, p. 78–80.

- ^ Averoes 2022, p. 59–62.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 304.

- ^ ISBN 9789812308375

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 51, 227.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Groeneveldt 1876, p. 22.

- ^ Burnet 2015.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 113.

- ^ a b Groeneveldt 1876, p. 23.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 30, 45.

- ^ a b c Nugroho 2011, p. 114.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 49.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 227.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 54, 228, 246, 258.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 109 and 115.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 60, 189.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 60, 219.

- ^ Nugroho 2011, p. 115, 118–119.

- ^ Groeneveldt 1876, p. 25 and 27.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 228, 229.

- ^ Groeneveldt 1876, p. 28.

- ^ a b Groeneveldt 1876, p. 27.

- ^ Muljana 2005, p. 203, 207, 211–212.

- ^ a b Nugroho 2009, p. 145.

- ^ Bade 2013, p. 62, 78, 228.

- ^ Shi-bi's notes book 162, in Groeneveldt (1876).

- ^ Zoetmulder, Petrus Josephus (1983). Kalangwan: Sastra Jawa Kuno Selayang Pandang. Penerbit Djambatan. p. 521.

- ^ Man 2007, p. 281.

- ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- ISBN 9787534818950.

- ISBN 978-0-904180-37-4

- ^ Yule, Sir Henry (1866). Cathay and the way thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China vol. 1. London: The Hakluyt Society. p. 89.

- ^ "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Chapter 9 Through the Straits of Malacca to China 1345–1346". The Travels of Ibn Battuta A Virtual Tour with the 14th Century Traveler. Berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- S2CID 191565174.

- ISBN 9780824824464.

- ISBN 9747551063.

- S2CID 162220129.

- ^ Lombard, Denys (2005). Nusa Jawa: Silang Budaya, Bagian 2: Jaringan Asia. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. Indonesian translation of Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) vol. 2. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

- ^ Hung et al. 2022, pp. 1–10.

Sources

- Averoes, Muhammad (2022). "Re-Estimating the Size of Javanese Jong Ship". HISTORIA: Jurnal Pendidik Dan Peneliti Sejarah. 5 (1): 57–64. S2CID 247335671.

- Bade, David W. (2013), Of Palm Wine, Women and War: The Mongolian Naval Expedition to Java in the 13th Century, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

- Bowring, Philip (2019), Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia's Great Archipelago, London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, ISBN 9781788314466

- Burnet, Ian (2015), Archipelago: A Journey Across Indonesia, Rosenberg Publishing

- Groeneveldt, Willem Pieter (1876), Notes on the Malay Archipelago and Malacca Compiled from Chinese Sources, Batavia: W. Bruining

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Hung, Hsiao-chun; Hartatik; Ma'rifat, Tisna Arif; Simanjuntak, Truman (2022), "Mongol fleet on the way to Java: First archaeological remains from the Karimata Strait in Indonesia", Archaeological Research in Asia, 29: 100327, S2CID 244553201

- Jákl, Jiří (2014). Literary Representations of War and Warfare in Old Javanese Kakawin Poetry (PhD thesis). The University of Queensland.

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012) [1957], Elleman, Bruce A. (ed.), China as Sea Power 1127-1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods, Singapore: NUS Press

- Man, John (2007), Kublai Khan: The Mongol king who remade China, London: Bantam Books, ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8

- Miksic, John Norman (2013), Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800, Singapore: NUS Press, ISBN 978-9971-69-558-3

- Muljana, Raden Benedictus Slamet (2005) [1965], Menuju Puncak Kemegahan (Sejarah Kerajaan Majapahit), Yogyakarta: LKiS Pelangi Aksara

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011), Majapahit Peradaban Maritim, Jakarta: Suluh Nuswantara Bakti, ISBN 978-602-9346-00-8

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2009), Meluruskan Sejarah Majapahit, Ragam Media

- Poesponegoro, Marwati Djoened; Notosusanto, Nugroho (2019) [2008], Sejarah Nasional Indonesia Edisi Pemutakhiran Jilid 2: Zaman Kuno, Jakarta: Balai Pustaka

Further reading

- Bade, David W. (2002), Khubilai Khan and the Beautiful Princess of Tumapel: the Mongols Between History and Literature in Java, Ulaanbaatar: A. Chuluunbat

- ISBN 978-0-543-94729-1

- Levathes, Louise (1994), When China Ruled the Seas, New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 54, ISBN 0-671-70158-4,

The ambitious khan [Kublai Khan] also sent fleets into the South China Seas to attack Annam and Java, whose leaders both briefly acknowledged the suzerainty of the dragon throne

- Sujana, Kadir Tisna (1987), Babad Majapahit, Jakarta: Balai Pustaka

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.