Valinor

| Valinor | |

|---|---|

The Great Sea, far to the West of Middle-earth |

Valinor (

Aman is known as "the Undying Lands", but the land itself does not cause mortals to live forever.

Scholars have described the similarity of Tolkien's myth of the attempt of Númenor to capture Aman to the biblical Tower of Babel and the ancient Greek Atlantis, and the resulting destruction in both cases. They note, too, that a mortal's stay in Valinor is only temporary, not conferring immortality, just as, in medieval Christian theology, the Earthly Paradise is only a preparation for the Celestial Paradise that is above.

Others have compared the account of the beautiful Elvish part of the Undying Lands to the

Geography

Physical

Valinor lies in Aman, a

Eldamar is "Elvenhome", the "coastal region of Aman, settled by the Elves", wrote Tolkien.

Calacirya (

In the extreme north-east, beyond the Pelóri, is the Helcaraxë, a vast ice sheet that joins the two continents of Aman and Middle-earth before the War of Wrath.[T 9] To prevent anyone from reaching the main part of Valinor's east coast by sea, the Valar create the Shadowy Seas, and within these seas they set a long chain of islands called the Enchanted Isles.[T 10][3]

Political

Valinor is the home of the Valar (singular Vala), spirits that often take humanoid form, sometimes called "gods" by the

Each Vala has his or her own region of the land. The Mansions of Manwë and Varda, two of the most powerful spirits, stands upon the top of Taniquetil.[T 11] Yavanna, the Vala of Earth, Growth, and Harvest, resides in the Pastures of Yavanna in the south of the land, west of the Pelóri. Nearby are the mansions of Yavanna's spouse, Aulë the Smith. Oromë, the Vala of the Hunt, lives in the Woods of Oromë to the north-east of the pastures. Nienna lives in the far west of the island. Just south of Nienna's home, and to the north of the pastures, are the Halls of Mandos; he lives with his spouse Vairë the weaver. To the east of the Halls of Mandos is the Isle of Estë, in the lake of Lórellin[T 11] within the Gardens of Lórien.[1]

In east-central Valinor at the Girdle of Arda is Valmar, the capital of Valinor (also called Valimar, the City of Bells), the residence of the Valar and the Maiar in Valinor. The first house of the Elves, the

In the northern inner foothills of the Pelóri, far to the north of Valmar, is Fëanor's city of Formenos, built after his banishment from Tirion.[T 13]

History

Years of the Trees

Valinor is established on the western continent

The Darkening of Valinor

Belatedly, the Valar learn what

The Hiding of Valinor

The Valar manage to save one last luminous flower from one of the Two Trees, Telperion, and one last luminous fruit from the other, Laurelin. These become the Moon and the Sun. The Valar carry out further titanic labours to improve the defences of Valinor. They raise the Pelóri mountains to even greater and sheerer heights. Off the coast, eastwards of Tol Eressëa, they create the Shadowy Seas and their Enchanted Isles; both the Seas and the Isles present numerous perils to anyone attempting to get to Valinor by sea.[T 10]

Later history

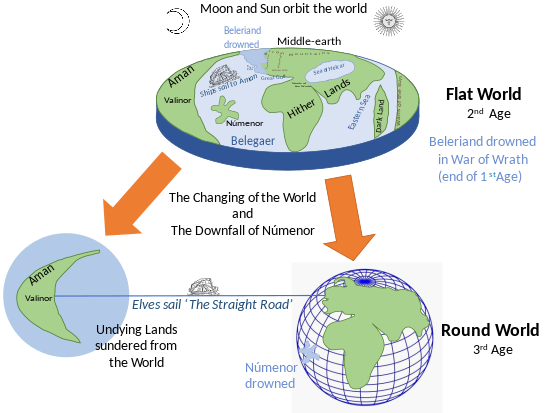

For centuries, Valinor take no part in the struggles between the Noldor and Morgoth in Middle-earth. But near the end of the

During the

Analysis

Paradise

Keith Kelly and Michael Livingston, writing in

| Tolkien | Catholicism |

Pearl, Dante's Paradiso |

|---|---|---|

| "that which is beyond Elvenhome and will ever be"[T 18] | Heaven | Celestial Paradise, "beyond" |

| Undying lands of Aman, Elvenhome in Valinor | Purgatory | Earthly Paradise, Garden of Eden

|

| Middle-earth | Earth | Earth |

The Tolkien scholar

Good against evil

The scholar of English literature

Original sin

The scholar of literature Richard Z. Gallant comments that while Tolkien made use of pagan Germanic heroism in his legendarium, and admired its Northern courage, he disliked its emphasis on "overmastering pride". This created a conflict in his writing. The pride of the Elves in Valinor resulted in a fall, analogous to the biblical fall of man. Tolkien described this by saying "The first fruit of their fall was in Paradise [Valinor], the slaying of Elves by Elves"; Gallant interprets this as an allusion to the fruit of the biblical tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the resulting exit from the Garden of Eden.[T 19][10] The leading prideful elf is Fëanor, whose actions, Gallant writes, set off the whole dark narrative of strife among the Elves described in The Silmarillion; the Elves fight and leave Valinor for Middle-earth.[10]

Lost home

Phillip Joe Fitzsimmons compares The Silmarillion's faraway Valinor, forbidden to Men and lost to the Elves, though it constantly calls to them to return, to Tolkien's fellow-Inkling, Owen Barfield's "lost home". Barfield writes of the loss of "an Edenic relationship with nature", part of his theory that man's purpose is to serve as "the Earth's self-consciousness".[11] Barfield argued that rationalism creates individualism, "unhappy isolation ... [and] the loss of a mutual relationship with nature."[11] Further, Barfield believed that ancient civilisations, as recorded in their languages, had a connection to and inner experience of nature, so that the modern situation represents a loss of that state of grace. Fitzsimmons states that the lost home motif recurs throughout Tolkien's writings. He does not suggest that Barfield influenced Tolkien, but that the ideas of the two men grew from "the same time, place, and even social circle".[11]

Atlantis, Babel

Kelly and Livingston state that while Aman could be home to Elves as well as Valar, the same was not true of mortal Men. The "prideful"

Celtic influence

The scholar of English literature

See also

- Asgard and Álfheimr in Norse mythology

- Elysium and Mount Olympus in Greek mythology

References

Primary

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #156 to Father R. Murray, SJ, November 1954

- ^ Tolkien 1955, "The Grey Havens", and Appendix B, entry for S.R. 1482 and 1541.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #249 to Michael Tolkien, October 1963

- ^ Tolkien 1994, "Quendi and Eldar"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1977, ch. 5 "Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië"

- Parma Eldalamberon, 17.

- Parma Eldalamberon, 17, p. 106.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- ^ a b c d e f Tolkien 1977, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 7 "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 2 "Of Aulë and Yavanna"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 8 "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 24 "Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Akallabêth"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 4 "The Field of Cormallen"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

Secondary

- ^ a b c d Fonstad 1991, pp. 1–4 Aman, 6–7 Valinor.

- ^ Tyler 2002, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ a b c d e Drout 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kelly & Livingston 2009.

- ^ Dickerson 2007.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 269–272.

- ^ a b c Burns 2005, pp. 152–154.

- ^ a b c Gallant 2014, pp. 109–129.

- ^ a b c Fitzsimmons 2016, pp. 1–8.

- ^ a b c Kocher 1974.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0802038067.

- ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Fitzsimmons, Phillip Joe (2016). "Glimpses of lost home in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and Owen Barfield". Faculty Articles & Research (3).

- ISBN 0-618-12699-6.

- Gallant, Richard Z. (2014). "Original Sin in Heorot and Valinor". S2CID 170621644.

- Kelly, A. Keith; Livingston, Michael (2009). "'A Far Green Country: Tolkien, Paradise, and the End of All Things in Medieval Literature". Mythlore. 27 (3).

- ISBN 0140038779.

- Oberhelman, David D. (2013) [2006]. "Valinor". In ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- ISBN 978-0261102750.

- OCLC 519647821.

- ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- ISBN 978-0-330-41165-3.