Gandalf

| Gandalf | |

|---|---|

Company of the Ring | |

| Weapon |

|

Gandalf is a protagonist in

As a wizard and the bearer of one of the

In The Hobbit, Gandalf assists the 13 dwarves and the hobbit

Tolkien once described Gandalf as an

The Gandalf character has been featured in radio, television, stage, video game, music, and film adaptations, including Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated film. His best-known portrayal is by Ian McKellen in Peter Jackson's 2001–2003 The Lord of the Rings film series, where the actor based his acclaimed performance on Tolkien himself. McKellen reprised the role in Jackson's 2012–2014 film series The Hobbit.

Names

Etymology

Tolkien derived the name Gandalf from Gandálfr, a

In-universe names

Gandalf is given several names and epithets in Tolkien's writings.

Each

Characteristics

Tolkien describes Gandalf as the last of the wizards to appear in

Warm and eager was his spirit (and it was enhanced by the ring Narya), for he was the Enemy of

Elf of the Wand'. For they deemed him (though in error) to be of Elven-kind, since he would at times work wonders among them, loving especially the beauty of fire; and yet such marvels he wrought mostly for mirth and delight, and desired not that any should hold him in awe or take his counsels out of fear. ... Yet it is said that in the ending of the task for which he came he suffered greatly, and was slain, and being sent back from death for a brief while was clothed then in white, and became a radiant flame (yet veiled still save in great need).[T 1]

Fictional biography

Valinor

In

As one of the Maiar, Gandalf was not a mortal Man but an angelic being who had taken human form. As one of those spirits, Olórin was in service to the Creator (

Middle-earth

The wizards arrived in

Gandalf's relationship with Saruman, the head of their Order, was strained. The Wizards were commanded to aid

The White Council

Gandalf suspected early on that an evil presence, the

Gandalf returned to Dol Guldur "at great peril" and learned that the Necromancer was indeed Sauron. The following year a White Council was held, and Gandalf urged that Sauron be driven out.

The Quest of Erebor

"

The Hobbit

Gandalf meets with

After escaping from the

He turns up again before the walls of Erebor disguised as an old man, revealing himself when it seems the Men of

The Lord of the Rings

Gandalf the Grey

Gandalf spent the years between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings travelling Middle-earth in search of information on Sauron's resurgence and Bilbo Baggins's mysterious ring, spurred particularly by Bilbo's initial misleading story of how he had obtained it as a "present" from Gollum. During this period, he befriended Aragorn and became suspicious of Saruman. He spent as much time as he could in the Shire, strengthening his friendship with Bilbo and Frodo, Bilbo's orphaned cousin and adopted heir.[T 13]

Gandalf returns to the Shire for Bilbo's "eleventy-first" (111th) birthday party, bringing many fireworks for the occasion. After Bilbo, as a prank on his guests, puts on the ring and disappears, Gandalf urges his old friend to leave the ring to Frodo, as they had planned. Bilbo becomes hostile, accusing Gandalf of trying to steal the ring. Alarmed, Gandalf tells Bilbo that is foolish. Coming to his senses, Bilbo admits that the ring has been troubling him, and leaves it behind for Frodo as he departs for Rivendell.[T 14]

Over the next 17 years, Gandalf travels extensively, searching for answers on the ring. He finds some answers in Isildur's scroll, in the archives of

Returning to the Shire, Gandalf confirms his suspicion by throwing the Ring into Frodo's hearth-fire and reading the writing that appears on its surface. He tells Frodo the history of the ring, and urges him to take it to Rivendell, warning of grave danger if he stays in the Shire. Gandalf says he will attempt to return for Frodo's 50th birthday party, to accompany him on the road; and that meanwhile Frodo should arrange to leave quietly, as the servants of Sauron will be searching for him.[T 15]

Outside the Shire, Gandalf encounters the wizard

In

In Rivendell, Gandalf helps

The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand

Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass."

Taking charge of the Fellowship (comprising nine representatives of the free peoples of

At the

Gandalf and the Balrog fall into a deep lake in Moria's underworld. Gandalf pursues the Balrog through the tunnels for eight days until they climb to the peak of

Gandalf the White

Gandalf is "sent back"

They travel to

Gandalf arrives in time to help to arrange the defences of Minas Tirith. His presence is resented by

"This, then, is my counsel," [said Gandalf.] "We have not the Ring. In wisdom or great folly it has been sent away to be destroyed, lest it destroy us. Without it we cannot by force defeat [Sauron's] force. But we must at all costs keep his Eye from his true peril... We must call out his hidden strength, so that he shall empty his land... We must make ourselves the bait, though his jaws should close on us... We must walk open-eyed into that trap, with courage, but small hope for ourselves. For, my lords, it may well prove that we ourselves shall perish utterly in a black battle far from the living lands; so that even if

Barad-dûrbe thrown down, we shall not live to see a new age. But this, I deem, is our duty."

After the battle, Gandalf counsels an attack against Sauron's forces at the

After the war, Gandalf crowns Aragorn as King Elessar, and helps him find a sapling of the

Two years later, Gandalf departs

Concept and creation

Appearance

Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter relates that Tolkien owned a postcard entitled Der Berggeist ("the mountain spirit"), which he labelled "the origin of Gandalf".[3] It shows a white-bearded man in a large hat and cloak seated among boulders in a mountain forest. Carpenter said that Tolkien recalled buying the postcard during his holiday in Switzerland in 1911. Manfred Zimmerman, however, discovered that the painting was by the German artist Josef Madlener and dates from the mid-1920s. Carpenter acknowledged that Tolkien was probably mistaken about the origin of the postcard.[4]

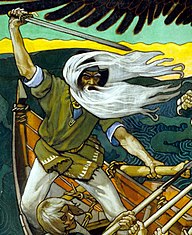

An additional influence may have been Väinämöinen, a demigod and the central character in Finnish folklore and the national epic Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot.[5] Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, magical singing voice.[6]

Throughout the early drafts, and through to the first edition of The Hobbit, Bladorthin/Gandalf is described as being a "little old man", distinct from a dwarf, but not of the full human stature that would later be described in The Lord of the Rings. Even in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf was not tall; shorter, for example, than Elrond[T 32] or the other wizards.[T 1]

Name

When writing

Tolkien came to regret his ad hoc use of

Guide

Gandalf's role and importance was substantially increased in the conception of The Lord of the Rings, and in a letter of 1954, Tolkien refers to Gandalf as an "angel incarnate".[T 36] In the same letter Tolkien states he was given the form of an old man in order to limit his powers on Earth. Both in 1965 and 1971 Tolkien again refers to Gandalf as an angelic being.[T 37][T 38]

In a 1946 letter, Tolkien stated that he thought of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer".[T 39] Other commentators have similarly compared Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his "Wanderer" guise—an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff,[10][11] or likened him to Merlin of Arthurian legend or the Jungian archetype of the "wise old man".[12]

| Attribute | Gandalf | Odin |

|---|---|---|

| Accoutrements | "battered hat" cloak "thorny staff" |

Epithet: "Long-hood" blue cloak a staff |

| Beard | "the grey", "old man" | Epithet: "Greybeard" |

| Appearance | the Istari (Wizards) "in simple guise, as it were of Men already old in years but hale in body, travellers and wanderers" as Tolkien wrote "a figure of 'the Odinic wanderer'"[T 40] |

Epithets: "Wayweary", "Wayfarer", "Wanderer" |

| Power | with his staff | Epithet: "Bearer of the [Magic] Wand" |

Eagles |

rescued repeatedly by eagles in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings |

Associated with eagles; escapes from Jotunheim as an eagle

back to Asgard |

In The Annotated Hobbit, Douglas Anderson likens Gandalf's role to the Rübezahl mountain spirit of German folktales. He states that the figure can appear as "a guide, a messenger, or a farmer", often depicted as "a bearded man with a staff".[13]

-

Gandalf, by 'Nidoart', 2013

The Tolkien scholar Charles W. Nelson described Gandalf as a "guide who .. assists a major character on a journey or quest .. to unusual and distant places". He noted that in both The Fellowship of the Ring and The Hobbit, Tolkien presents Gandalf in these terms. Immediately after the

Someone said that intelligence would be needed in the party. He was right. I think I shall come with you.[14]

Nelson notes the similarity between this and Thorin's statement in The Hobbit:[14]

We shall soon .. start on our long journey, a journey from which some of us, or perhaps all of us (except our friend and counsellor, the ingenious wizard Gandalf) may never return.[14]

Nelson gives as examples of the guide figure the

Nelson writes that there is equally historical precedent for wicked guides, such as

Christ-figure

The critic Anne C. Petty, writing about "

The philosopher

Christ -like attribute |

Gandalf | Frodo | Aragorn |

|---|---|---|---|

Sacrificial death,

resurrection |

Dies in Moria,

reborn as Gandalf the White[c] |

Symbolically dies under Morgul-knife, healed by Elrond[24] |

Takes Paths of the Dead,

reappears in Gondor |

| Saviour | All three help to save Middle-earth from Sauron | ||

| Threefold Messianic symbolism | Prophet | Priest | King |

Adaptations

In the BBC Radio dramatisations, Gandalf has been voiced by Norman Shelley in The Lord of the Rings (1955–1956),[25] Heron Carvic in The Hobbit (1968), Bernard Mayes in The Lord of the Rings (1979),[26] and Sir Michael Hordern in The Lord of the Rings (1981).[27]

Ian McKellen portrayed Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings film series (2001–2003), directed by Peter Jackson, after Sean Connery and Patrick Stewart both turned down the role.[30][31] According to Jackson, McKellen based his performance as Gandalf on Tolkien himself:

We listened to audio recordings of Tolkien reading excerpts from Lord of the Rings. We watched some BBC interviews with him—there's a few interviews with Tolkien—and Ian based his performance on an impersonation of Tolkien. He's literally basing Gandalf on Tolkien. He sounds the same, he uses the speech patterns and his mannerisms are born out of the same roughness from the footage of Tolkien. So, Tolkien would recognize himself in Ian's performance.[32]

McKellen received widespread acclaim

Charles Picard portrayed Gandalf in the 1999 stage production of The Two Towers at Chicago's Lifeline Theatre.[42][43] Brent Carver portrayed Gandalf in the 2006 musical production The Lord of the Rings, which opened in Toronto.[44]

Gandalf appears in The Lego Movie, voiced by Todd Hanson.[45] Gandalf is a main character in the video game Lego Dimensions and is voiced by Tom Kane.[46]

Gandalf has his own movement in

Notes

- ^ Meaning "Grey Pilgrim"

- Eruintervening to change the course of the world.

- ^ Other commentators such as Jane Chance have compared this transformed reappearance to the Transfiguration of Jesus.[23]

References

Primary

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tolkien 1980, part 4, ch. 2, "The Istari"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 4, ch. 5, "The Window on the West"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1955, Appendix B

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- The Quest of Erebor"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 1, "An Unexpected Party"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 2, "Roast Mutton"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 3, "A Short Rest"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, "Out of the Frying-Pan into the Fire"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 7, "Queer Lodgings"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 17, "The Clouds Burst"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, "The Last Stage"

- ^ a b c d e f g Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2, "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 1, "A Long-Expected Party"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 2, "The Shadow of the Past"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 11, "A Knife in the Dark"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch.3, "The Ring Goes South"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 4, "A Journey in the Dark"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 5, "The Bridge of Khazad-Dum"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 5, "The White Rider"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 6, "The King of the Golden Hall"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 7, "Helm's Deep"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 8, "The Road to Isengard"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 10, "The Voice of Saruman"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 11, "The Palantír"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 1, "Minas Tirith"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 10, "The Black Gate Opens"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 4, "The Field of Cormallen"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 5, "The Steward and the King"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 7, "Homeward Bound"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 9, "The Grey Havens"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1, "Many Meetings".

- ^ Tolkien 1988, p. ix

- ^ Tolkien 1988, p. 452

- Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #156 to R. Murray, SJ, November 1954

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #268 to Miss A.P. Northey, January 1965

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #325 to R. Green, July 1971

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #107 to Allen & Unwin, December 1946

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #119 to Allen & Unwin, February 1949

Secondary

- ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0.

- ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0.

- ISBN 978-0-0492-8037-3.

- ^ Zimmerman, Manfred (1983). "The Origin of Gandalf and Josef Madlener". Mythlore. 9 (4). East Lansing, Michigan: Mythopoeic Society. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-1438119069.

- ^ Siikala, Anna-Leena (30 July 2007). "Väinämöinen". Kansallisbiografia (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-9816607-1-4.

- ^ "Halfdan the Black Saga (Ch. 1. Halfdan Fights Gandalf and Sigtryg) in Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla: A History of the Norse Kings, transl. Samuel Laing (Norroena Society, London, 1907)". mcllibrary.org. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

The same autumn he went with an army to Vingulmark against King Gandalf. They had many battles, and sometimes one, sometimes the other gained the victory; but at last they agreed that Halfdan should have half of Vingulmark, as his father Gudrod had had it before.

- ^ Shippey, Tom. "Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy". Nordals.hi.is. Archived from the original on 30 August 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

We know that Tolkien had great difficulty in getting his story going. In my opinion, he did not break through until, on February 9, 1942, he settled the issue of languages

- ^ a b Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1997). An investigation of the Teutonic god Óðinn; and a study of his relationship to J. R.R. Tolkien's character, Gandalf (Thesis). University of New England.

- ^ ISBN 0-8020-3806-9.

- ISBN 0-87548-303-8.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1937, pp. 148–149.

- ^ JSTOR 43308562.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ISBN 9780415289443.

- ISBN 978-0-333-29034-7.

- ISBN 978-0-80282-497-4. Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b Kreeft, Peter J. (November 2005). "The Presence of Christ in The Lord of the Rings". Ignatius Insight. Archived from the original on 24 November 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-61147-065-9. Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Schultz, Forrest W. (1 December 2002). "Christian Typologies in The Lord of the Rings". Chalcedon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- ISBN 978-1-136-78554-2. Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-7821-9090-5.

- ^ "Mind's Eye The Lord of the Rings (1979)". SF Worlds. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings BBC Adaptation (1981)". SF Worlds. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Huffington Post. New York City. 21 December 2011. Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Kajava, Jukka (29 March 1993). "Tolkienin taruista on tehty tv-sarja: Hobitien ilme syntyi jo Ryhmäteatterin Suomenlinnan tulkinnassa" [Tolkien's tales have been turned into a TV series: The Hobbits have been brought to live in the Ryhmäteatteri theatre]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2020.(subscription required)

- Hearst Magazines UK. Archived from the originalon 16 October 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "New York Con Reports, Pictures and Video". TrekMovie. 9 March 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- Huffington Post Media Group. Archivedfrom the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Moore, Sam (23 March 2017). "Sir Ian McKellen to reprise role of Gandalf in new one-man show". NME. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Acting Awards, Honours, and Appointments". Ian McKellen. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters: 30. Gandalf". Empire. London, England: Bauer Media Group. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ISBN 0-00-717558-2.

- ^ "Ian McKellen as Gandalf in The Hobbit". Ian McKellen. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "Gandalf". Behind the Voice Actors. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Gandalf". Behind the Voice Actors. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Gandalf". Behind the Voice Actors. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "TheOneRing.net | Events | World Events | The Two Towers at Chicago's Lifeline Theatre". archives.theonering.net. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- American Theatre. 18: 13–15.

- Playbill. Playbill. Archivedfrom the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Gandalf". Behind the Voice Actors. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

Todd Hansen is the voice of Gandalf in The LEGO Movie.

- ^ Lang, Derrick (9 April 2015). "Awesome! 'Lego Dimensions' combining bricks and franchises". The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado: Digital First Media. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Der Herr der Ringe, Johan de Meij - Sinfonie Nr.1". Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5660-4. Archivedfrom the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- OCLC 9552942.

- OCLC 1042159111.

- OCLC 519647821.

- ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7.

![Odin, the Wanderer by Georg von Rosen, 1886[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/Georg_von_Rosen_-_Oden_som_vandringsman%2C_1886_%28Odin%2C_the_Wanderer%29.jpg/225px-Georg_von_Rosen_-_Oden_som_vandringsman%2C_1886_%28Odin%2C_the_Wanderer%29.jpg)

![The Rübezahl as a bearded guide with staff, in a 1903 illustration[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Rubezahl_-_deutsche_Volksmarchen_1903_%28142146889%29_Bearded_Guide_with_Staff.jpg/306px-Rubezahl_-_deutsche_Volksmarchen_1903_%28142146889%29_Bearded_Guide_with_Staff.jpg)