Christianity and science

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Most scientific and technical innovations prior to the Scientific Revolution were achieved by societies organized by religious traditions. Ancient Christian scholars pioneered individual elements of the scientific method. Historically, Christianity has been and still is a patron of sciences.[1] It has been prolific in the foundation of schools, universities and hospitals,[2][3][4][5][6] and many Christian clergy have been active in the sciences and have made significant contributions to the development of science.[7]

Events in Christian Europe, such as the Galileo affair, that were associated with the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment led some scholars such as John William Draper to postulate a conflict thesis, holding that religion and science have been in conflict throughout history. While the conflict thesis remains popular in atheistic and antireligious circles, it has lost favor among most contemporary historians of science.[22][23][24] Most contemporary historians of science agree that the occurrence with Galileo was an exception, with the relationship between science and Christianity, and have corrected numerous false interpretations of said affair.[25][26][27][28]

Overview

Most sources of knowledge available to the

Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with

France, early 15th century.

Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas[33] held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. Augustine Argued:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars ... Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking non-sense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men.[34]

The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on.[35] Also, the sense that God created the world as a self-operating system is what motivated many Christians throughout the Middle Ages to investigate nature.[36]

The

Modern historians of science such as

David C. Lindberg states that the widespread popular belief that the Middle Ages was a time of ignorance and superstition due to the Christian church is a "caricature". According to Lindberg, while there are some portions of the classical tradition which suggest this view, these were exceptional cases. It was common to tolerate and encourage critical thinking about the nature of the world. The relation between Christianity and science is complex and cannot be simplified to either harmony[47] or conflict,[48] according to Lindberg.[49] Lindberg reports that "the late medieval scholar rarely experienced the coercive power of the church and would have regarded himself as free (particularly in the natural sciences) to follow reason and observation wherever they led. There was no warfare between science and the church."[50] Ted Peters in Encyclopedia of Religion writes that although there is some truth in the "Galileo's condemnation" story but through exaggerations, it has now become "a modern myth perpetuated by those wishing to see warfare between science and religion who were allegedly persecuted by an atavistic and dogma-bound ecclesiastical authority".[51] In 1992, the Catholic Church's seeming vindication of Galileo attracted much comment in the media:

Generations of historians and sociologists have discovered many ways in which Christians, Christian beliefs, and Christian institutions played crucial roles in fashioning the tenets, methods, and institutions of what in time became modern science. They found that some forms of Christianity provided the motivation to study nature systematically.[52]

A degree of concord between science and religion can be seen in religious belief and empirical science. The belief that God created the world and therefore humans, can lead to the view that he arranged for humans to know the world. This is underwritten by the doctrine of

During the Enlightenment, a period "characterized by dramatic revolutions in science" and the rise of Protestant challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church via individual liberty, the authority of Christian scriptures became strongly challenged. As science advanced, acceptance of a literal version of the Bible became "increasingly untenable" and some in that period presented ways of interpreting scripture according to its spirit on its authority and truth.[54]

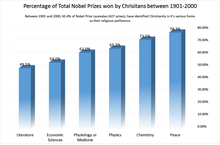

Regarding the subject on the distribution of Nobel Prizes by religion between 1901 and 2000, the data taken from Baruch A. Shalev, shows that between the years 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religion. 65.4% have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. Overall, Christians have won a total of 78.3% of all the Nobel Prizes in Peace, 72.5% in Chemistry, 65.3% in Physics, 62% in Medicine, 54% in Economics and 49.5% of all Literature awards.[55]

History

Roots of scientific revolution

Between 1150 and 1200, Christian scholars had traveled to Sicily and Spain to retrieve the writings of Aristotle, which had been lost to the West after the Fall of the Roman Empire. This produced a period of cultural ferment that one "modern historian has called the twelfth century renaissance".

Modern western universities have their origins directly in the Medieval Church.[61][62][63][64][65] They began as cathedral schools, and all students were considered clerics.[66] This was a benefit as it placed the students under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and thus imparted certain legal immunities and protections. The cathedral schools eventually became partially detached from the cathedrals and formed their own institutions, the earliest being the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Oxford (1096), and the University of Paris (c. 1150).[67][68][69]

Some scholars have noted a direct tie between "particular aspects of traditional Christianity" and the rise of science.

Influence of biblical worldviews on early modern science

At first according to

Oxford historian Peter Harrison is another who has argued that a Biblical worldview was significant for the development of modern science. Harrison contends that Protestant approaches to the book of scripture had significant, if largely unintended, consequences for the interpretation of the book of nature.[82] [page needed] Harrison has also suggested that literal readings of the Genesis narratives of the Creation and Fall motivated and legitimated scientific activity in seventeenth-century England. For many of its seventeenth-century practitioners, science was imagined to be a means of restoring a human dominion over nature that had been lost as a consequence of the Fall.[83][page needed]

Historian and professor of religion

Reconciliation in Britain in the early 20th century

In Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-twentieth-century Britain, historian of biology

In the twentieth century, several

Branches of Christianity

Catholicism

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the

The

Today almost all historians agree that Christianity (Catholicism as well Protestantism) moved many early-modem intellectuals to study nature systematically. Historians have also found that notions borrowed from Christian belief found their ways into scientific discourse, with glorious results.[100]

— Noah J. Efron

Galileo once stated "The intention of the

One view, first propounded by

In opposition to this view, some historians of science, including non-Catholics such as

Throughout history many

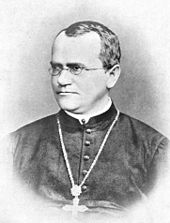

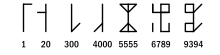

Cistercian in science

The Catholic Cistercian order used its own numbering system, which could express numbers from 0 to 9999 in a single sign.[107][108] According to one modern Cistercian, "enterprise and entrepreneurial spirit" have always been a part of the order's identity, and the Cistercians "were catalysts for development of a market economy" in twelfth-century Europe.[109] Until the Industrial Revolution, most of the technological advances in Europe were made in the monasteries.[109] According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."[110] Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement [that] could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries.[111]

The English science historian

Jesuits in science

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the teaching of science in Jesuit schools, as laid down in the Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu ("The Official Plan of studies for the Society of Jesus") of 1599,[113] was almost entirely based on the works of Aristotle.

The Jesuits, nevertheless, have made numerous significant contributions to the development of science. For example, the Jesuits have dedicated significant study to earthquakes, and seismology has been described as "the Jesuit science".[114] The Jesuits have been described as "the single most important contributor to experimental physics in the seventeenth century".[115] According to Jonathan Wright in his book God's Soldiers, by the eighteenth century the Jesuits had "contributed to the development of pendulum clocks, pantographs, barometers, reflecting telescopes and microscopes, to scientific fields as various as magnetism, optics and electricity. They observed, in some cases before anyone else, the colored bands on Jupiter's surface, the Andromeda nebula and Saturn's rings. They theorized about the circulation of the blood (independently of Harvey), the theoretical possibility of flight, the way the moon affected the tides, and the wave-like nature of light."[116]

The

The missionary efforts and other work of the

Protestant influence

Protestantism has promoted economic growth and entrepreneurship, especially in the period after the Scientific and the Industrial Revolution.[119][120] Scholars have identified a positive correlation between the rise of Protestantism and human capital formation,[121] work ethic,[122] economic development,[123] and the development of the state system.[124]

According of Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States by

between 1901 and 1972.Some of the first colleges and

Quakers in science

The Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers, encouraged some values which may have been conducive to encouraging scientific talents. A theory suggested by David Hackett Fischer in his book Albion's Seed indicated early Quakers in the US preferred "practical study" to the more traditional studies of Greek or Latin popular with the elite. Another theory suggests their avoidance of dogma or clergy gave them a greater flexibility in response to science.[143]

Despite those arguments a major factor is agreed to be that the Quakers were initially discouraged or forbidden to go to the major law or humanities schools in Britain due to the

Because of these issues it has been stated Quakers are better represented in science than most religions. There are sources, Pendlehill (

Eastern Christian influence

Among the Copts in Egypt, every monastery and probably every church once had its own library of manuscripts.[156]

In the fifth century AD, nine Christian Syrian Monks translated Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac works into the Ethiopian language of

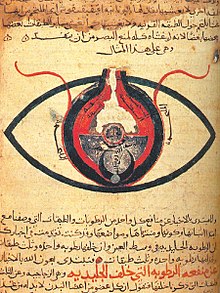

In the field of Optics, Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn-Ishaq's textbook on ophthalmology called the Ten Treatises on the Eye, which was written in 950 A.D., remained the authoritative source on the subject in the western world until the 1800s.[164]

It was a Christian scholar and Bishop from Nisibis named Severus Sebokht who was the first to describe and incorporate Indian mathematical symbols in the mid 7th century, which were then adopted into Islamic culture and are now known as the Arabic numerals.[165][166][167]

During the fourth through the seventh centuries, scholarly work in the Syriac and Greek languages was either newly initiated, or carried on from the Hellenistic period. Centers of learning and of transmission of classical wisdom included colleges such as the

The commom and persistent myth claiming that Islamic scholars "saved" the classical work of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers from destruction and then graciously passed it on to Europe is baseless. According to the myth, these works would otherwise have perished in the long European Dark Age between the fifth and tenth centuries. Ancient Greek texts and Greek culture were never "lost" to be somehow "recovered" and "transmitted" by Islamic scholars, as many keep claiming: the texts were always there, preserved and studied by the scholars and monks of the Byzantines and passed on to the rest of Europe and to the Islamic world at various times. Aristotle had been translated in France at the abbey of Mont Saint-Michel before translations of Aristotle into Arabic (via the Syriac of the Christian scholars from the conquered lands of the Byzantine Empire). Michael Harris points out:[177]

The great writings of the classical era, particularly those of Greece ... were always available to the Byzantines and to those Western peoples in cultural and diplomatic contact with the Eastern Empire.... Of the Greek classics known today, at least seventy-five percent are known through Byzantine copies.

Historian John Julius Norwich adds that “much of what we know about antiquity—especially Hellenic and Roman literature and Roman law—would have been lost forever if it weren’t for the scholars and scribes of Constantinople.”[178]

The

Paper, which the Muslims received from China in the eighth century, was being used in the Byzantine Empire by the ninth century. There were very large private libraries, and monasteries possessed huge libraries with hundreds of books that were lent to people in each monastery's region. Thus were preserved the works of classical antiquity.[183][184]

When Saint Cyril was sent by the Byzantine emperor in an embassy to the Arabs in the ninth century, he astonished his Muslim hosts with his knowledge of philosophy and science as well as theology. Historian Maria Mavroudi recounts:[185]

When asked how it was possible for him to know all that he did, he [Cyril] drew an analogy between the Muslim reaction to his erudition and the pride of someone who kept sea water in a wine skin and boasted of possessing a rare liquid. He finally encountered someone from a region by the sea, who explained that only a madman would brag about the contents of the wine skin, since people from his own homeland possessed an endless abundance of sea water. The Muslims are like the man with the wine skin and the [Greeks] like the man from the sea because, according to the saint's concluding remark in his response, all learning emanated from the [Greeks].

Perspectives on evolution

In recent history, the theory of

Most scientists have rejected creation science for several reasons, including that its claims do not refer to natural causes and cannot be tested. In 1987, the

Modern reception

Individual scientists' views

Throughout history many

Prominent modern scientists advocating Christian belief include Nobel Prize–winning physicists

Scientific Revolution

Some scholars have noted a direct tie between "particular aspects of traditional Christianity" and the rise of science.[18][71]

The history professor Peter Harrison attributes Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution:

historians of science have long known that religious factors played a significantly positive role in the emergence and persistence of modern science in the West. Not only were many of the key figures in the rise of science individuals with sincere religious commitments, but the new approaches to nature that they pioneered were underpinned in various ways by religious assumptions. ... Yet, many of the leading figures in the scientific revolution imagined themselves to be champions of a science that was more compatible with Christianity than the medieval ideas about the natural world that they replaced.[222]

Nobel Prize

According to 100 Years of Nobel Prizes a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of

In an estimate by scholar

In an estimate made by Weijia Zhang from Arizona State University and Robert G. Fuller from University of Nebraska–Lincoln, between 1901 and 1990, 60% of Physics Nobel prize winners had Christian backgrounds.[231]

According of Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States by

between 1901 and 1972.Criticism

Events in Christian Europe, such as the Galileo affair, that were associated with the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment led scholars such as John William Draper to postulate a conflict thesis, holding that religion and science have been in conflict methodologically, factually and politically throughout history. This thesis is held by several scientists like Richard Dawkins and Lawrence Krauss. While the conflict thesis remains popular in atheistic and antireligious circles, it has lost favor among most contemporary historians of science,[22][23][24][232] and the majority of scientists in elite universities in the U.S. do not hold a conflict view.[233]

More recently,

Trial of Galileo

In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), describing observations made with his new telescope. These and other discoveries exposed difficulties with the understanding of the heavens that was common at the time. Scientists, along with the Catholic Church, had adopted Aristotle's view of the earth as fixed in place, since Aristotle's rediscovery 300 years prior.[236] Jeffrey Foss writes that, by Galileo's time, the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic view of the universe had become "fully integrated with Catholic theology".[237]: 285

Scientists of the day largely rejected Galileo's assertions, since most had no telescope, and Galileo had no physical theory to explain how planets could orbit the sun which, according to Aristotelian physics, was impossible. (That would not be resolved for another hundred years.) Galileo's peers alerted religious authorities to his "errors" and asked them to intervene.[237]: 285–286 In response, the church forbade Galileo from teaching it, though it did not forbid discussing it, so long as it was clear it was merely a hypothesis. Galileo published books and asserted scientific superiority.[237]: 285 He was summoned before the Roman Inquisition twice. First warned, he was next sentenced to house arrest on a charge of "grave suspicion of heresy".[237]: 286

The Galileo affair has been considered by many to be a defining moment in the history of the relationship between religion and science. Since the creation of the Conflict thesis by Andrew Dickson White and John William Draper in the late nineteenth century, religion has been depicted as oppressive and oppositional to science.[238] Edward Daub explains that, while "twentieth century historians of science dismantled White and Draper's claims, it is still popular in public perception".[239] Casting Galileo's story as a contest between science and religion is an oversimplification, writes Jeffrey Foss.[237]: 286 Galileo was heir to a long scientific tradition with deep medieval Christian roots.[46]

See also

|

By tradition:

In the US:

|

|

Notes

- ISBN 0-691-11436-6, page 123

- ^ ISBN 9789059724877.

Many of the medieval universities in Western Europe were born under the aegis of the Catholic Church, usually as cathedral schools or by papal bull as Studia Generali.

- ^ ISBN 9780810884939.

All the great European universities-Oxford, to Paris, to Cologne, to Prague, to Bologna—were established with close ties to the Church.

- ^ ISBN 9781135205157.

Europe established schools in association with their cathedrals to educate priests, and from these emerged eventually the first universities of Europe, which began forming in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

- ISBN 9789401796361.

- ISBN 9781502606853.

- ^ Wright, Jonathan (2004). God's Soldiers: Adventure, Politics, intrigue and Power: A History of the Jesuits. HarperCollins. p. 200.

- ^ Wallace, William A. (1984). Prelude, Galileo and his Sources. The Heritage of the Collegio Romano in Galileo's Science. N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ISBN 0-521-34804-8.

- ISBN 0-87220-563-0.

- ISBN 978-0813515304.

- ^ ISBN 0521814561.

... Many of the scientists who contributed to these developments were Christians...

- ^ ISBN 978-0191025136.

... the Christian contribution to science has been uniformly at the top level, but it has reached that level and it has been sufficiently strong overall ...

- ^ ISBN 978-0830875276.

... . Many of the early leaders of the scientific revolution were Christians of various stripes, including Roger Bacon, Copernicus, Kepler, Francis Bacon, Galileo, Newton, Boyle, Pascal, Descartes, Ray, Linnaeus and Gassendi...

- ^ ISBN 978-1787203044.

Many prominent Catholic physicians and psychologists have made significant contributions to hypnosis in medicine, dentistry, and psychology.

- ISBN 978-0935047370

- ^ Harrison, Peter. "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4

- ISBN 0521814561.

- ^ ISBN 9781317610366.

- ^ ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

The conflict thesis, at least in its simple form, is now widely perceived as a wholly inadequate intellectual framework within which to construct a sensible and realistic historiography of Western science

- ^ ISBN 9780226750200.

In the late Victorian period it was common to write about the 'warfare between science and religion' and to presume that the two bodies of culture must always have been in conflict. However, it is a very long time since these attitudes have been held by historians of science.

- ^ a b Brooke, J. H. (1991). Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 42.

In its traditional forms, the conflict thesis has been largely discredited.

- ISBN 978-1-62466-132-7.

..one of the most common myths widely held about the trial of Galileo, including several elements: that he "saw" the earth's motion (an observation still impossible to make even in the twenty-first century); that he was "imprisoned" by the Inquisition (whereas he was actually held under house arrest); and that his crime was to have discovered the truth. And since to condemn someone for this reason can result only from ignorance, prejudice, and narrow-mindedness, this is also the myth that alleges the incompatibility between science and religion.

- ISBN 978-3-631-56229-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7459-5371-7.

- ^ McMullin, Ernan (2008). "Robert Bellarmine". In Gillispie, Charles (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Scribner & American Council of Learned Societies.

- ISBN 978-0-02-865704-2.

- ^ a b Religion and Science, John Habgood, Mills & Brown, 1964, pp., 11, 14–16, 48–55, 68–69, 90–91, 87

- ISBN 978-0-8006-6273-8.

- ^ Knight, Christopher C. (2008). "God's Action in Nature's World: Essays in Honour of Robert John Russell". Science & Christian Belief. 20 (2): 214–215.

- ISBN 0-8018-8401-2.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo. Genesi Ad Litteram. Paulist Press. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Grant 2006, pp. 111–114

- ^ Grant 2006, pp. 105–106

- ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- ^ a b George Saliba (27 April 2006). "Islamic Science and the Making of Renaissance Europe". Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Byzantine Medicine – Vienna Dioscurides". Antiqua Medicina. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ ISBN 0-87220-563-0.)

- ^ "What Time Is It in the Transept?". D. Graham Burnett book review of J.L.Heilbron's work, The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories. The New York Times. 24 October 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ISBN 0-226-48214-6.

- ISBN 0-306-80637-1.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (September 1998). "Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), IV". Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ISBN 0-8028-4772-2.

- ^ ISBN 9780674057418.

- .

- .

- ^ David C. Lindberg, "The Medieval Church Encounters the Classical Tradition: Saint Augustine, Roger Bacon, and the Handmaiden Metaphor", in David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers, ed. When Science & Christianity Meet (Chicago: University of Chicago Pr., 2003).

- ^ quoted in: Peters, Ted. "Science and Religion". Encyclopedia of Religion p. 8182

- ^ Quoted in Ted Peters, "Science and Religion", Encyclopedia of Religion, p. 8182

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- ^ "Religion and Science (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ Enlightenment. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2017.

- ISBN 9788126902781.

- ^ Matthews & Platt 1991, p. 221.

- ^ Matthews & Platt 1991, p. 222.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-56762-6.

- ^ a b Matthews & Platt 1991, p. 250.

- ISBN 978-0-393-86840-1.

- ISBN 978-90-5972-487-7.

Many of the medieval universities in Western Europe were born under the aegis of the Catholic Church, usually as cathedral schools or by papal bull as Studia Generali.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-8493-9.

All the great European universities-Oxford, to Paris, to Cologne, to Prague, to Bologna—were established with close ties to the Church.

- ISBN 978-1-135-20515-7.

Europe established schools in association with their cathedrals to educate priests, and from these emerged eventually the first universities of Europe, which began forming in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

- ISBN 978-94-017-9636-1.

- ISBN 978-1-5026-0685-3.

- ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126–127, 282–298

- ISBN 978-2-86847-344-8. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism", in The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 257.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4,, that Christianity was fundamentally responsible for the successes of seventeenth-century science. It would be a mistake of equal magnitude, however, to overlook the intricate interlocking of scientific and religious concerns throughout the century.

It would be indefensible to maintain, with Hooykaas and Jaki

- ^ Becker, George (1992), The Merton Thesis: Oetinger and German Pietism, a significant negative case, Sociological Forum (Springer) 7 (4), pp. 642–660

- ISBN 9781405105958

- ^ Andrew Dickson White. History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (Kindle Locations 1970–2132)

- ISBN 978-0-674-05741-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-275-95904-3.

- . Studies in the History of Science and Christianity.

- ISBN 978-0-674-05741-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-226-11280-2, pages 308–321

- ^ "Finally, and most importantly, Hooykaas does not of course claim that the Scientific Revolution was exclusively the work of Protestant scholars." Cohen(1994) p 313

- ^ Cohen(1994) p 313. Hooykaas puts it more poetically: "Metaphorically speaking, whereas the bodily ingredients of science may have been Greek, its vitamins and hormones were biblical."

- ^ Peter Harrison, The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science (Cambridge, 1998).

- ^ Peter Harrison, The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science (Cambridge, 2007); see also Charles Webster, The Great Instauration (London: Duckworth, 1975)

- ISBN 9780520056923.

- ^ The Anglican Origins of Modern Science, Isis, Volume 71, Issue 2, June 1980, 251–267; this is also noted on page 366 of Science and Religion, John Hedley Brooke, 1991, Cambridge University Press

- ^ John Dillenberger, Protestant Thought and Natural Science (Doubleday, 1960).

- Eerdmans, 1991).

- ISBN 0-521-23961-3, page 19. See also Peter Harrison, "Newtonian Science, Miracles, and the Laws of Nature", Journal of the History of Ideas 56 (1995), 531–53.

- Stanley L. Jaki

- ISBN 0-691-11436-6, page 123

- ISBN 0-226-06858-7. Front dustcover flap material

- Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.. Across the Atlantic, the Society of Ordained Scientists and Christians in Science are similar affiliation in Great Britain.

As to specifically Christian theists, an example of continue presence would be the American Scientific Affiliation. It currently has about two thousand members, all of whom affirm the Apostles' Creed as part of joining the association, and most of whom hold Ph.D.s in the natural sciences. Their active journal is Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia". New Advent. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ISBN 9780674038486.

- ISBN 9789401796361.

- ISBN 9781502606853.

- ^ de Ridder-Symoens (1992), pp. 47–55

- ISBN 0-87249-376-8.

- ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism," in The New Cambridge Medieval History. Volume V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007. p. 257.

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- ISBN 0-521-58841-3.

- John Paul II, 3 October 1981 to the Pontifical Academy of Science, "Cosmology and Fundamental Physics"

- ^ "J.L. Heilbron". London Review of Books. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ISBN 0-226-48214-6.

- ISBN 0-306-80637-1.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (September 1998). "Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), IV". Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ King, David (1995). "A forgotten Cistercian system of numerical notation". Citeaux Commentarii Cistercienses. 46 (3–4): 183–217.

- OCLC 630115876.

- ^ a b Rob Baedeker (24 March 2008). "Good Works: Monks build multimillion-dollar business and give the money away". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods.

- ^ Woods, p 33

- ^ a b Herbert Thurston. "Cistercians in the British Isles". Catholic Encyclopedia. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "The Jesuit Ratio Studiorum of 1599" (PDF). 27 December 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ISBN 0-691-12807-3, p. 68.

- ISBN 0-520-05538-1.

- ISBN 0-385-50080-7.

- ^ Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p. 212.

- ISBN 0-895-26038-7.

- S2CID 7528944.

- ISBN 978-0520031944.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S2CID 204438351.

- ISSN 2572-1496.

- ISBN 978-0-8135-1530-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4051-0595-8

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (1998), Handout for course 'The Scientific Revolution' at The Scientific Revolution

- ^ Becker, George (1992), The Merton Thesis: Oetinger and German Pietism, a significant negative case, Sociological Forum (Springer) 7 (4), pp. 642–660

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harriet Zuckerman, Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States New York, The Free Press, 1977 , p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-)

- ^ ISBN 9780300133486.

For instance, concerning the religious origins of American laureates, 72 percent are Protestant ...

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: The Early History of Harvard University". News.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Increase Mather". Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2022., Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Princeton University Office of Communications. "Princeton in the American Revolution". Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2011. The original Trustees of Princeton University "were acting in behalf of the evangelical or New Light wing of the Presbyterian Church, but the college had no legal or constitutional identification with that denomination. Its doors were to be open to all students, 'any different sentiments in religion notwithstanding.'"

- ISBN 0231130082.

- ^ Childs, Francis Lane (December 1957). "A Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshman". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ISBN 9780195359053.

Of all these northern schools, only Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania were historically Anglican; the rest are associated with revivalist Presbyterianism or Congregationalism.

- ISBN 9781136249808.

Princeton was Presbyterian, while Columbia and Pennsylvania were Episcopalian.

- ^ "Duke University's Relation to the Methodist Church: the basics". Duke University. 2002. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

Duke University has historical, formal, on-going, and symbolic ties with Methodism, but is an independent and non-sectarian institution ... Duke would not be the institution it is today without its ties to the Methodist Church. However, the Methodist Church does not own or direct the University. Duke is and has developed as a private nonprofit corporation which is owned and governed by an autonomous and self-perpetuating Board of Trustees

- ^ "Boston University Names University Professor Herbert Mason United Methodist Scholar/Teacher of the Year". Boston University. 2001. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

Boston University has been historically affiliated with the United Methodist Church since 1839 when the Newbury Biblical Institute, the first Methodist seminary in the United States, was established in Newbury, Vermont.

- ^ W.L. Kingsley et al., "The College and the Church," New Englander and Yale Review 11 (Feb 1858): 600. accessed 2010-6-16 Archived April 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Note: Middlebury is considered the first "operating" college in Vermont as it was the first to hold classes in Nov 1800. It issued the first Vermont degree in 1802; UVM followed in 1804.

- ISBN 978-1847185655.

- ISBN 9780857281128.

- ^ Porter, Roy (2001). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine. Cambridge University Press. p. 67."The major ninth-century medical figure in Baghdad was a Christian Arab, Hunain ibn Ishaq, an amazingly accurate and productive scholar, who traveled to the Greek Byzantine empire in search of rare Galenic treatises."

- ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- ISBN 9780226070803. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Ferguson, Kitty Pythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2008, (page number not available – occurs toward end of Chapter 13, "The Wrap-up of Antiquity"). "It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language."

- ^ Rosenthal, Franz The Classical Heritage in Islam The University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1975, p. 6

- ^ Adamson, London Peter The Great Medieval Thinkers: Al-Kindi Oxford University Press, New York, 2007, p. 6. London Peter Adamson is a Lecturer in Late Ancient Philosophy at King's College.

- ISBN 978-0-521-24015-4. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- JSTOR 1523325.

- ^ Brague, Rémi. "Assyrians Contributions To The Islamic Civilization". christiansofiraq.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- ^ Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 1973, p. 204' Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol.1, A-K, Index, 2006, p. 304.

- ISBN 9780226070803.

Neither were there any Muslims among the Ninth-Century translators. Amost all of them were Christians of various Eastern denominations: Jacobites, Melchites, and, above all, Nestorians... A few others were Sabians.

- ISBN 9780837076119.

- ISBN 9780852446331.

- ISBN 9780974445076.

- ^ Vööbus, Arthur (1961). "The statutes of the School of Nisibis".

- ISBN 9780415061322.

- ISBN 9780710019035.

- ISBN 9780520019973.

- ISBN 9781504034692.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.47–48, 59, 96–97, 171–72

- ISBN 9781101189993.

- ISBN 9780486161167.

- ISBN 9780801899102.

- ^ Kaser, Karl The Balkans and the Near East: Introduction to a Shared History p. 135.

- ^ Yazberdiyev, Dr. Almaz Libraries of Ancient Merv Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Yazberdiyev is Director of the Library of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat.

- ^ Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 3rd edition, p. 216

- ^ Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol.1, A – K, Index, 2006, p. 451

- ^ Britannica, Nestorian

- ^ The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:2 Mehmet Mahfuz Söylemez, The Jundishapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions, p.3.

- doi:10.1086/444875.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5737-5.

- ISBN 978-84-600-8154-8.

- ISBN 9780810877153– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9780141928593.

- ^ "Byzantine Medicine – Vienna Dioscurides". Antiqua Medicina. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ Byzantines in Renaissance Italy

- ^ "Fall of Constantinople". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Lindberg, David. (1992) The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. p. 349.

- ISBN 9780884023326.

- ^ Vryonis Jr., Speros (1967). Byzantium and Europe.

- S2CID 161272020.

- ^ "Religion and Science". stanford.edu. 2022.

- ^ Numbers 2006, pp. 268–285

- ISBN 978-0-393-33073-1.and to prove the creation account as described in Scripture.

Most creationists are simply people who choose to believe that God created the world-either as described in Scripture or through evolution. Creation scientists, by contrast, strive to use legitimate scientific means both to argue against evolutionary theory

- ^ Numbers 2006, pp. 271–274

- ISBN 978-0-679-64288-6.

- ^ Numbers 2006, pp. 399–431

- ^ The Origin of Rights, Roger E. Salhany, Toronto, Calgary, Vancouver:Carswell p. 32-34

- ^ "The legislative history demonstrates that the term "creation science," as contemplated by the state legislature, embraces this religious teaching." Edwards v. Aguillard

- ISBN 978-1-4165-4274-2.

- ^ Schultz, Colin. "The Pope Would Like You to Accept Evolution and the Big Bang". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- Polski słownik biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), vol. XIV, Wrocław, Polish Academy of Sciences, 1969, p. 11.

- ISBN 0-521-56671-1.

- ^ "Because he would not accept the Formula of Concord without some reservations, he was excommunicated from the Lutheran communion. Because he remained faithful to his Lutheranism throughout his life, he experienced constant suspicion from Catholics." John L. Treloar, "Biography of Kepler shows man of rare integrity. Astronomer saw science and spirituality as one." National Catholic Reporter, 8 October 2004, p. 2a. A review of James A. Connor Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order amid Religious War, Political Intrigue and Heresy Trial of His Mother, Harper San Francisco.

- ^ Richard S. Westfall – Indiana University The Galileo Project. (Rice University). Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ "The Boyle Lecture". St. Marylebow Church.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1625). The Essayes Or Covnsels, Civill and Morall, of Francis Lo. Vervlam, Viscovnt St. Alban. London. p. 90. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Leibniz on the Trinity and the Incarnation: Reason and Revelation in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007, pp. xix–xx).

- ^ Swedenborg, E. The True Christian Religion, particularly sections 163–184 (New York: Swedenborg Foundation, 1951).

- ^ "Gli scienziati cattolici che hanno fatto lItalia (Catholic scientists who made Italy)". Zenit. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- OCLC 53933110.

- ^ Grimaux, Edouard. Lavoisier 1743–1794. (Paris, 1888; 2nd ed., 1896; 3rd ed., 1899), page 53.

- ^ "John Dalton". Science History Institute. June 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- doi:10.1119/1.14636.

- ^ Hutchinson, Ian (2006) [January 1998]. "James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian Proposition". Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ McCartney & Whitaker (2002), reproduced on Institute of Physics website

- ^ Vallery-Radot, Maurice (1994). Pasteur. Paris: Perrin. pp. 377–407.

- ^ Cantor, pp. 41–43, 60–64, and 277–280.

- ISBN 9780226068596. "Both Lord Rayleigh and J. J. Thomson were Anglicans."

- ^ Seeger, Raymond. 1986. "J. J. Thomson, Anglican," in Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 38 (June 1986): 131–132. The Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. ""As a Professor, J.J. Thomson did attend the Sunday evening college chapel service, and as Master, the morning service. He was a regular communicant in the Anglican Church. In addition, he showed an active interest in the Trinity Mission at Camberwell. With respect to his private devotional life, J.J. Thomson would invariably practice kneeling for daily prayer, and read his Bible before retiring each night. He truly was a practicing Christian!" (Raymond Seeger 1986, 132)."

- ^ "Christian Influences In The Sciences". rae.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "World's Greatest Creation Scientists from Y1K to Y2K". creationsafaris.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- S2CID 39722460.

- ISBN 978-0813515304.

- S2CID 56239703.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (8 May 2012). "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Shalev, Baruch (2005). 100 Years of Nobel Prizes. p. 59

- ^ Baruch A. Shalev (2003), 100 Years of Nobel Prizes, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p. 57

- ^ Shalev 2003, p. 60

- ^ 33.2% of 6.7 billion world population (under the section 'People') "World". CIA world facts. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007.

- ^ "The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions". foreignpolicy.com. March 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "A review of the Nobel prizes between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religions. Most (65.4%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. While separating Roman Catholic from Protestants among Christians proved difficult in some cases, available information suggests that more Protestants were involved in the scientific categories and more Catholics were involved in the Literature and Peace categories." Shalev 2003, p. 57

- S2CID 250743713.

- ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

... while [John] Brooke's view [of a complexity thesis rather than an historical conflict thesis] has gained widespread acceptance among professional historians of science, the traditional view remains strong elsewhere, not least in the popular mind.

- .

- ^ "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization". Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. "Introduction" in Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion. Ed. Ronald Numbers. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009. Page 6.

- ISBN 978-1-4042-0314-3.

- ^ ISBN 9781551116242.

- ^ Aechtner, Thomas."Galileo Still Goes to Jail: Conflict Model Persistence within Introductory Anthropology Materials"; and Garrett Kenney,"Why Religion Matters and the Purposes of Higher Education: A Dialogue with Huston Smith."." Zygon® 50.1 (2015): 209–226. loc=Abstract

- ^ Daub, Edward E. "Demythologizing White's Warfare of Science with Theology." American Biology Teacher 40.9 (1978): 553–56.

Works cited

- Numbers, Ronald L. (2006). The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02339-0.

- Shalev, Baruch A. (2003). 100 Years of Nobel Prizes. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0278-1.

- Thomas, Anne (24 April 2000), This I Know Experimentally, Spring 2000 Monday Night Lecture Series: Science and Religion, Pendle Hill (published 6 October 2003), archived from the original on 1 May 2006, retrieved 29 June 2009

Further reading

- Buxhoeveden, Daniel; Woloschak, Gayle, eds. (2011). Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church (1. ed.). Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409481614.

- Spierer, Eugen. God-of-the-Gaps Arguments in Light of Luther's Theology of the Cross. Archived 19 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Matthews, Roy T.; Platt, F. DeWitt (1991). The Western Humanities. Mayfield Publishing Co. ISBN 0874847850.

External links

- Christianity And The Scientist by Ian G. Barbour Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Cambridge Christians in Science (CiS) group Archived 3 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Christians in Science website

- Ian Ramsey Centre, Oxford

- The Society of Ordained Scientists-Mostly Church of England

- "Science in Christian Perspective" The (ASA)

- Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation (CSCA)

- The International Society for Science & Religion's founding members.(Of various faiths including Christianity)

- Association of Christians in the Mathematical Sciences

- Secular Humanism.org article on Science and Religion Archived 19 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine