Catholic art

Catholic art is

The earliest surviving artworks are the painted

The

Beginnings

In the 4th century, the

Much Christian art borrowed from Imperial imagery, including

Byzantine and Eastern art

The dedication of

This achievement was checked by the controversy over the use of graven images and the proper interpretation of the Second Commandment, which led to the crisis of

The art of

Although the influence has often been resisted, especially in Russia, Catholic art has also affected Orthodox depictions in many respects, especially in countries like

Catholic doctrine on sacred images

The Catholic theological position on sacred images has remained effectively identical to that set out in the

To the Western church images were just objects made by craftsmen, to be utilized for stimulating the senses of the faithful, and to be respected for the sake of the subject represented, not in themselves. Although in popular devotional practice a tendency to go beyond these limits has often been present, the church was, before the advent of the idea of collecting old art, usually brutal in disposing of images no longer needed, much to the regret of art historians. Most monumental sculpture of the first millennium that has survived was broken up and reused as rubble in the re-building of churches.

In practical matters relating to the use of images, as opposed to their theoretical place in theology, the Libri Carolini were at the anti-iconic end of the spectrum of Catholic views, being for example rather disapproving of the lighting of candles before images. Such views were often expressed by individual church leaders, such as the famous example of Saint

Early Middle Ages

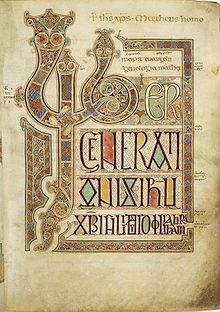

While the Western Roman Empire's political structure collapsed after the fall of Rome, the Church continued to fund art where it could. The most numerous surviving works of the early period are illuminated manuscripts, at this date all presumably created by the clergy, often including abbots and other senior figures. The monastic hybrid between "barbarian" decorative styles and the book in the

The 9th century Emperor

Ivory carvings, often for book covers, drew on the

Charlemagne had a life-size crucifix with the figure of Christ in precious metal in his

Romanesque

Carvings in stone adorned the exteriors and interiors, particularly the tympanum above the main entrance, which often featured a Christ in Majesty or in Judgement, and the large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the start of the period. The capitals of columns were also often elaborately carved with figurative scenes. The ensemble of large and well-preserved churches at Cologne, then the largest city north of the Alps, and Segovia in Spain, are among the best places today to appreciate the impact of the new larger churches on a city landscape, but many individual buildings exist, from Durham, Ely and Tournai Cathedrals to large numbers of individual churches, especially in Southern France and Italy. In more prosperous areas, many Romanesque churches survive covered up by a Baroque makeover, much easier to do with these than a Gothic church.

Few of the large wall-paintings that originally covered most churches have survived in good condition. The

Gothic art

Gothic art emerged in France in the mid-12th century. The

Gothic art was often

Iconography was affected by changes in theology, with depictions of the

In Early Netherlandish painting, from the richest cities of Northern Europe, a new minute realism in oil painting was combined with subtle and complex theological allusions, expressed precisely through the highly detailed settings of religious scenes. The Mérode Altarpiece (1420s) of Robert Campin and the Washington Van Eyck Annunciation or Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (both 1430s, by Jan van Eyck) are examples.[7]

In the 15th century, the introduction of cheap

For the wealthy, small panel paintings, even polyptychs in oil painting, were becoming increasingly popular, often showing donor portraits alongside, though often much smaller than, the Virgin or saints depicted. These were usually displayed in the home.

Renaissance art

The brief

Most fifteenth-century pictures from this period were religious pictures. This is self-evident, in one sense, but “religious pictures” refers to more than just a certain range of subject matter; it means that the pictures existed to meet institutional ends. The Church commissioned artwork for three main reasons: The first was indoctrination, clear images were able to relay meaning to an uneducated person. The second was ease of recall, depictions of saints and other religious figures allow for a point of mental contact. The third is to incite awe in the heart of the viewer,

The Protestant Reformation was a holocaust of art in many parts of Europe. Although

In Rome, the sack of 1527 by the Catholic Emperor Charles V and his largely Protestant mercenary troops was enormously destructive both of art and artists, many of whose biographical records end abruptly. Other artists managed to escape to different parts of Italy, often finding difficulty in picking up the thread of their careers. Italian artists, with the odd exception like Girolamo da Treviso, seem to have had little attraction to Protestantism. In Germany, however, the leading figures such as Albrecht Dürer and his pupils, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Danube school, and Hans Holbein the Younger all followed the Reformers. The development of German religious painting had come to an abrupt halt by about 1540, although many prints and book illustrations, especially of Old Testament subjects, continued to be produced.

Council of Trent

Italian painting after 1520, with the notable exception of the art of

The decree confirmed the traditional doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person themselves, not the image, and further instructed that:

...every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust... there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no one be allowed to place, or cause to be placed, any unusual image, in any place, or church, howsoever exempted, except that image have been approved of by the bishop ...[11]

Ten years after the decree

Baroque art

Baroque art, developing over the decades following the Council of Trent, though the extent to which this was an influence on it is a matter of debate, certainly met most of the council's requirements, especially in the earlier, simpler phases associated with the

New iconic subjects popularized in the Baroque period included the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and the Immaculate Conception of Mary; the definitive iconography for the latter seems to have been established by the master and then father-in-law of Diego Velázquez, the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco, to whom the Inquisition in Seville also contracted the approval of new images. The Assumption of Mary became a very common subject, and (despite a Caravaggio of the subject) the Death of the Virgin became almost extinct in Catholic art; Molanus and others had written against it.

18th century

In the 18th Century, secular Baroque developed into the still more flamboyant but lighter

By now the rate of production of religious art was noticeably slowing down. After a spate of building and re-building in the Baroque period, Catholic countries were mostly clearly overstocked with churches, monasteries and convents, in the case of some places such as Naples, almost absurdly so. The Church was now less important as a patron than royalty and the aristocracy, and the middle class demand for art, mostly secular, was increasing rapidly. Artists could now have a successful career painting portraits, landscapes, still lifes or other genre specialisms, without ever painting a religious subject – something hitherto unusual in the Catholic countries, though long the norm in Protestant ones. The number of sales of paintings, metalwork and other church fittings to private collectors increased during the century, especially in Italy, where the Grand Tour gave rise to networks of dealers and agents. Leonardo da Vinci's London Virgin of the Rocks was sold to the Scottish artist and dealer Gavin Hamilton by the church in Milan that it was painted for in about 1781; the version in the Louvre having apparently been diverted from the same church three centuries earlier by Leonardo himself, to go to the King of France.

The wars following the

19th and 20th centuries

The 19th Century saw a widespread repudiation by both Catholic and Protestant churches of Classicism, which was associated with the

Outside these and similar movements, the establishment art world produced much less religious painting than at any time since the Roman Empire, though many types of applied art for church fittings in the Gothic style were made. Commercial popular Catholic art flourished using cheaper techniques for mass-reproduction. Colour lithography made it possible to reproduce coloured images cheaply, leading to a much broader circulation of holy cards. Much of this art continued to use watered-down versions of Baroque styles. The Immaculate Heart of Mary was a new subject of the 19th century, and new apparitions at Lourdes and Fátima, as well as new saints, provided new subjects for art.

Architects began to revive other earlier Christian styles, and experiment with new ones, producing results such as

Modern Catholic artists include Brian Whelan, Efren Ordoñez, Ade Bethune, Imogen Stuart, and Georges Rouault.[16]

21st century

The early adoption of modernist styles at the dawn of the 21st century continued with the trends from the 20th century. Artists began to experiment with materials and colours. In many cases this contributed to simplifications which led to resemblance to the early Christian art. Simplicity was seen as the best way to bring pure Christian messages to the viewer.

Subjects

Some of the most common subjects depicted in Catholic art:

- Annunciation

- Nativity of Jesus in art

- Adoration of the Magi

- Adoration of the shepherds

- Baptism of Jesus

- The Last Supper

- Arrest of Jesus

- The Raising of the Cross

- The Crucifixion

- Descent from the Cross

- Noli me tangere

- Ascension of Jesus

- Christ in Majesty

Mary:

- Roman Catholic Marian art

- Life of the Virgin

- Christ taking leave of his Mother

- Death of the Virgin

- Assumption of the Virgin Mary in art

- Coronation of the Virgin

- The Holy family

- Madonna (art)

- Madonna and Child

- Hortus conclusus

- Holy Kinship

Other:

See also

- Christian art

- Catholic culture

- Roman Catholic Marian art

- Early Renaissance painting

- Baroque architecture

- List of illuminated manuscripts

- Western Painting

Footnotes

- ISBN 0-691-01830-8

- ^ Jean Lassus. Landmarks of Western Art. Ed. B Myers, T Copplestone. (Hamlyn Publishing, 1965, 1985) p.187.

- ^ W.F. Volbach, Elfenbeinarbeiten der Spätantike und des frühen Mittelalters (Mainz, 1976).

- ^ T. Mathews, The early churches of Constantinople: architecture and liturgy (University Park, 1971); N. Henck, "Constantius ho Philoktistes?", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001), 279-304 (available online Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Michelle P. Brown. How Christianity came to Britain and Ireland. (Lion Hudson, 2006) pp. 176, 177, 191

- ^ Male, Emile (1913) The Gothic Image, Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p 165-8, English trans of 3rd edn, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions) is a classic work on French Gothic church art

- ISBN 0-06-430133-8analyses all these works in detail. See also the references in the articles on the works.

- ^ The birth and growth of Utrecht Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alberti, Leon Battista. On Painting. Princeton University Press, 1981, p. 215.

- ^ Roy Strong. Lost Treasures of Britain. (Viking Penguin, 1990) pp.47-65.

- ^ "CT25". history.hanover.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ "Transcript of Veronese's testimony". Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ISBN 0-521-56568-5

- ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- ^ The death of Medieval Art Extract from book by Émile Mâle

- ^ "Georges Rouault, French Expressionist Painter". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

References

- Levey, Michael (1961). From Giotto to Cézanne. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20024-6.

- Beckwith, John (1969). early Medieval Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20019-X.

- Rice, David Talbot (1997). Art of the Byzantine Era. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20004-1.

- Myers, Bernard; Trewin Copplestone Ed. (1985) [1965]. Landmarks of Western Art. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-35840-2.

- Brown, Michelle P. (2006). How Christianity Came to Britain and Ireland. Lion Hudson. ISBN 0-7459-5153-8.

- Strong, Roy (1990). Lost Treasures of Britain. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-83383-5.

- ISBN 9788887915402.

External links

- Christian Iconography from Augusta State University.

- "The Function of Art". Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Art