History of Sabah

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Sabah can be traced back to about 23–30,000 years ago when evidence suggests the earliest human settlement in the region existed. The history is interwoven with the

Prehistoric Sabah

During the

The earliest ascertained wave of human migration, believed to be

Pre-15th century

During the 7th century CE, a settled community known as Vijayapura, a tributary to the

The Brunei Annals in 1410 mentioned about a Chinese settlement or province centring in the Kinabatangan Valley in the east coast surrounding Kinabatangan River founded by a man known as Ong Sum Ping. This is consistent with the recent discovery of timber coffins in the Agop Batu Tulug cave in the Kinabatangan Valley, belong to the Dusun Sukang tribe. The coffins, adorned with carvings believed to resemble similar cultural practices in China and Vietnam, are believed to date back from around 700 to 1,000 years ago (11th to 14th century).[18] From the 14th century, the Majapahit empire expanded its influence towards Brunei and most of the coastal region of Borneo.

Bruneian Empire and the Sulu Sultanate

The Sultanate of Brunei began after the ruler of Brunei embraced

In 1658, the Sultan of Brunei ceded the northern and eastern portion of Borneo to the Sultanate of Sulu in compensation for the latter's help in settling the

-

The extent of theBruneian Empire in the 15th century, under Sultan Bolkiahrule.

-

The extent of the Sultanate of Sulu in 1822.

British North Borneo

In 1761,

In 1865, the American Consul General of Brunei,

On the east coast of North Borneo near Sandakan, William Cowie, on behalf of Dent's company,

As the population was too small to fully economically exploit the region, the company brought in Chinese people mainly

In 1888, North Borneo became a

The First Native's Paramount Leader was Pehin Orang Kaya-Kaya Koroh Santulan of Ansip & Kadalakan, also known as old Keningau town, "The father of former Sabah State Minister Tan Sri Stephen (Suffian) Koroh, and Sabah's fifth State Governor Tun Thomas (Ahmad) Koroh (the elder brother of Suffian)". Santulan which also a Pengeran, the father to Pehin Orang Kaya-Kaya Koroh was a Murut descendant of Omar Ali Saifuddin I, the 18th Sultan of Brunei.[citation needed]

-

Flag of North Borneo

-

Civil ensign of North Borneo

-

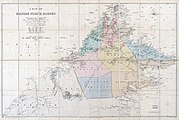

Map of British North Borneo by Edward Stanford in 1888, kept by the United States Library of Congress.

-

Map of North Borneo from the British Library, 1888

-

Joseph William Torrey been given a permission by the Sultanate of Brunei to operating from the entire northern portion of the island of Borneo from Sulaman on the west to river Pietan on the East and the states of Paitan, Sugot, Banggayan, Labuk, Sandakan, China Bantangan, Gagayan Mumiang, Benuni and Kimanis, together with the islands of Banguey, Palawan and Balabao on 24 November 1865.

-

(Left) The first concession treaty was signed by SultanBaron de Overbeck as the Maharaja Sabah, Rajah Gaya and Sandakan, signed on 29 December 1877.[1]

(Right) The second concession treaty was signed by Sultan Jamal ul-Azam of Sulu, also appointing Baron de Overbeck as Dato Bendahara and Raja Sandakan on 22 January 1878, approximately three weeks after signature of the first treaty.[3]

Japanese occupation and Allied liberation

As part of the Second World War Japanese forces landed in

In Keningau during World War II, Korom was a rebel and some said he was a Sergeant with the North Borneo Armed Constabulary. It was claimed that he spied for the Allied Forces by pretending to be working for the Japanese. He provided intelligence on Japanese positions and some credited him with the escape of 500 Allied POWs. Fighting alongside Korom in his platoon was Garukon, Lumanib, Kingan, Mikat, Pensyl, Gampak, Abdullah Hashim, Ariff Salleh, Langkab, Polos, Nuing, Ambutit, Lakai, Badau and many more including the Chinese.

In

The war ended with the official surrender by Lieutenant-General

-

Japanese troops march through the streets of Labuan on 14 January 1942.

-

Japanese civilians and soldiers leaving North Borneo after the surrender of Japan to the Australian forces.

Self-government and the formation of Malaysia

On 31 August 1963, North Borneo attained self-government. The idea for the formation of a union of the former British colonies, namely, Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo was mooted as early as the late 19th century, but it was Tunku Abdul Rahman who officially announced the proposal of wider federation in May 1961. It also seemed that this idea was supported by the British.[40] There was a call for complete independence on that date by it was denied by the British Governor who remained in power until Malaysia Day.[41] In 1962, the Cobbold Commission was set up to determine whether the people of Sabah and Sarawak favoured the proposed union. The commission had found that the union was generally favoured by the people but wanted certain terms and conditions incorporated to safeguard the interest of the people. The commission had also noted some opposition from the people but decided that such opposition was minor. The Commission published its report on 1 August 1962 and had made several recommendations. Unlike in Singapore, however, no referendum was ever conducted in Sabah.[42]

Most ethnic community leaders of Sabah, namely, Mustapha representing the Muslims,

-

Mustapha Harun(second right).

-

Donald Stephens officiating the Keningau Oath Stone on 31 August 1964, an important agreement remembrance that has been promised between Sabahans and the Malaysian federal government.

Indonesian confrontation and the Brunei Revolt

Leading up to the formation of Malaysia until 1966, Indonesia adopted a hostile policy towards Malaya and subsequently Malaysia, which was backed by British forces. This undeclared war stems from what Indonesian President Sukarno perceive as an expansion of British influence in the region and his intention to wrest control over the whole of Borneo under the Indonesian republic.

Around the same time, there were proposals from certain parties, particularly by the Brunei People's Party, for the formation of a North Borneo Federation consisting of Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei. The proposal culminated in rebel attacks in Brunei and some parts of Sabah and Sarawak. The rebellion was foiled by the Bruneian Army with the help of the British colonials in December 1962.

-

Men from the indigenous tribes of Sabah and Sarawak were recruited by the Malaysian government as Border Scouts under the command of Richard Noone and other officers from the Senoi Praaq to counter the Indonesian infiltrations.

-

Royal Marines Commando unit armed with machine gun and Sten gun patrolling using a boat in the river on Serudong, Sabah to guard the state during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation.

Philippine claim to eastern Sabah

The Philippines maintains a

However, Malaysia considers this dispute as a "non-issue" as it interprets the 1878 agreement as that of cession and that it deems that the residents of Sabah had exercised their right to self-determination when they joined to form the Malaysian federation in 1963.[46][47]

Post-independence

-

Flag of Sabah from 1963 to 1982.

-

Flag of Sabah from 1982 to 1988.

In 1985, following the

From 1990 to 1991, several

In 2000, the state capital

In early 2013, an armed group which identified themselves as the "Royal Sulu Army"

The Malaysia-Sulu Case

In 2019, the Sabah region received global attention due to the Malaysia-Sulu Case. The case involved a multi-billion dollar arbitration claim made by self-proclaimed descendants of the last Sultan of Sulu Empire against the Malaysian government.

The arbitration claim featured the region of Sabah and a colonial-era agreement.[59] The 1878 agreement involved a deal with the Sulu Sultan for the use of his territory now falling in present-day Malaysia. The Malaysian government continued honoring the agreement until 2013 and stopped payment henceforth, leading to the arbitration case.

The claimants demanded compensation worth US$32 billion. In January 2022, Spanish arbitrator Gonzalo Stampa ruled in favor of claimants, awarding an arbitration settlement of US$15 billion, the largest such award in international arbitration history.[60] However, the award was eventually struck down by the Hague Court of Appeal on June 27, 2023.[61][62]

References

- ^ a b Rozan Yunos (21 September 2008). "How Brunei lost its northern province". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-674-92615-8.

- ^ a b Rozan Yunos (7 March 2013). "Sabah and the Sulu claims". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-4141-8.

- ^ Steven Dutch (14 October 2003). "Plate Tectonics and Earth History". Natural and Applied Sciences. University of Wisconsin–Green Bay. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

The South China Sea opened as Borneo moved away from China.

- ^ a b c "About Sabah". Sabah Tourism Promotion Corporation and Sabah State Museum. Sabah Education Department. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-945971-73-3.

- ^ Durie Rainer Fong (10 April 2012). "Archaeologists hit 'gold' at Mansuli". The Star. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Prehistoric site discovered". Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment of Sabah. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Ruben Sario (24 May 201). "Prehistoric settlement unearthed". The Star. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-907065-36-1.

- PMID 1346259.

- ISBN 978-1-60608-307-9.

- ^ Henry Wise (1846). A Selection from Papers Relating to Borneo and the Proceedings at Sarāwak of James Brooke ... publisher not identified. pp. 10–.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-4903-7.

- ISBN 978-962-593-180-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-38121-9.

- ^ Haslin Gaffor (10 April 2007). "Coffins dating back 1,000 years are found in the Kinabatangan Valley". The Star. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Sultan-Sultan Brunei" (in Malay). Brunei History Centre. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7007-1698-2.

- ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3.

- ^ Rozan Yunos (24 October 2011). "In search of Brunei Malays outside Brunei". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-983-100-095-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-979-799-083-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7146-2594-2.

- ^ British Government (1877). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1877)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers).

- ^ Francesco Lamendola (30 September 2010). "Quando la vecchia Austria voleva stabilirsi nelle isole dell'Oceano Indiano [Riferimento al tentativo di creare colonie penali italiane nel Borneo]" (in Italian). Arianna Editrice. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84974-6.

- ^ Charles A. Fisher (1971). South-East Asia: A Social, Economic and Political Geography. Methuen. p. 669.

- ^ British Government (1878). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1878)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers).

- ^ British Government (1885). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1885)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ C.Buckley: A School History of Sabah, London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1968

- ISBN 978-981-230-812-2.

- ^ Andson Cowie; William Clark Cowie (1893). English-Sulu-Malay Vocabulary: With Useful Sentences, Tables, and C. editor. pp. 10–.

- ^ Ken Goodlet, Tawau : The Making of a Tropical Community, Opus Publication, 2010

- ^ Riwanto Tirtosudarmo (2003). "Between Larantuka and Tawau: Exploring Florenese Migration Space" (PDF). The Research Centre for Society and Culture, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Indonesia.

- Berita Harian (in Malay). Archived from the originalon 17 April 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ Peter C. Richards (6 December 1947). "New Flag Over Pacific Paradise". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ISBN 978-981-230-783-5.

- ^ Johan M. Padasian: Sabah History in pictures (1881-1981), Sabah State Government, 1981

- ^ Luke Rintod (8 March 2013). "There was no Sabah referendum". Free Malaysia Today. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013.

- Muzium Sabah, Kota Kinabalu. 1992

- ^ Ramlah binti Adam, Abdul Hakim bin Samuri, Muslimin bin Fadzil: "Sejarah Tingkatan 3, Buku teks", published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (2005)

- ^ Mohamad, Kadir (2009). "Malaysia's territorial disputes – two cases at the ICJ : Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Ligitan and Sipadan [and the Sabah claim] (Malaysia/Indonesia/Philippines)" (PDF). Institute of Diplomacy and Foreign Relations (IDFR) Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia: 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

Map of British North Borneo, highlighting in yellow colour the area covered by the Philippine claim, presented to the Court by the Philippines during the Oral Hearings at the ICJ on 25 June 2001

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ruben Sario; Julie S. Alipala; Ed General (17 September 2008). "Sulu sultan's 'heirs' drop Sabah claim". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- ^ Jerome Aning (22 April 2009). "Sabah legislature refuses to tackle RP claim". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-134-96099-6.

- ^ "More revenue from oil". Daily Express. 19 June 2004. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Laws of Malaysia A585 Constitution (Amendment) (No.2) Act 1984". Government of Malaysia. Department of Veterinary Services. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Chronicle of Malaysia, Editions Didier Millet (2007). "1986".

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (1 October 1987). "Kota Kinabalu Journal; With Houses on Stilts and Hopes in Another Land". The New York Times.

- ^ "Abdication of Responsibility: The Commonwealth and Human Rights" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. October 1991.

- ^ "The Court finds that sovereignty over the islands of Ligitan and Sipadan belongs to Malaysia". International Court of Justice. 17 December 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Why 'Sultan' is dreaming". Daily Express. 27 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015.

- ^ Najiah Najib (30 December 2013). "Lahad Datu invasion: A painful memory of 2013". Astro Awani.

- ^ "Semporna villagers beat to death ex-Moro commander". The Star. 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Nur Misuari involved, says Zahid". Bernama. MySinChew English. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014.

- ^ "The Paris Court of Appeal rules on the Sulu Sultan Heirs' colossal fight against Malaysia: the rise and fall of one the most controversial ad hoc arbitration cases ever? | LexisNexis Blogs". www.lexisnexis.co.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Report: M'sia ordered to pay almost RM63b to Sulu sultan's descendants". Yahoo News. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "MALAYSIA SCORES LANDMARK WIN AGAINST SULU CLAIMANTS – PM ANWAR". Prime Minister's Office of Malaysia Official Website. 27 June 2023.

- ^ "Dutch court rules sultan's heirs cannot seize Malaysian assets". Reuters. 27 June 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

![(Left) The first concession treaty was signed by Sultan Abdul Momin of Brunei, appointing Baron de Overbeck as the Maharaja Sabah, Rajah Gaya and Sandakan, signed on 29 December 1877.[1] (Right) The second concession treaty was signed by Sultan Jamal ul-Azam of Sulu, also appointing Baron de Overbeck as Dato Bendahara and Raja Sandakan on 22 January 1878, approximately three weeks after signature of the first treaty.[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Brunei_%28left%29_Sulu_%28right%29_Overbeck.jpg/165px-Brunei_%28left%29_Sulu_%28right%29_Overbeck.jpg)