History of theatre

The history of theatre charts the development of

Origins

There is no conclusive evidence that theater evolved from ritual, despite the similarities between the performance of ritual actions and theatre and the significance of this relationship.[2] This similarity of early theatre to ritual is negatively attested by Aristotle, who in his Poetics defined theatre in contrast to the performances of sacred mysteries: theatre did not require the spectator to fast, drink the kykeon, or march in a procession; however theatre did resemble the sacred mysteries in the sense that it brought purification and healing to the spectator by means of a vision, the theama. The physical location of such performances was accordingly named theatron.[3]

According to the historians

European theatre

Greek theatre

Greek theatre, most developed in Athens, is the root of the Western tradition; theatre is a word of Greek origin.

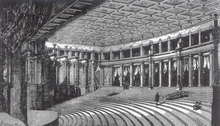

Roman theatre

Western theatre developed and expanded considerably under the

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) into several Greek territories between 270 and 240 BC, Rome encountered Greek drama.[22] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 BC-476 AD), theatre spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theatre was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[23] While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 BC marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[22][i] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favour of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[24]

The first important works of

The Roman comedies that have survived are all

No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—

In contrast to Ancient Greek theatre, the theatre in Ancient Rome did allow female performers. While the majority were employed for dancing and singing, a minority of actresses are known to have performed speaking roles, and there were actresses who achieved wealth, fame and recognition for their art, such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola and Fabia Arete: they also formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy.[32]

Transition and early medieval theatre, 500–1050

As the

From the 5th century, Western Europe was plunged into a period of general disorder that lasted (with a brief period of stability under the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century) until the 10th century. As such, most organized theatrical activities disappeared in Western Europe.[citation needed] While it seems that small nomadic bands travelled around Europe throughout the period, performing wherever they could find an audience, there is no evidence that they produced anything but crude scenes.[34] These performers were denounced by the Church during the Dark Ages as they were viewed as dangerous and pagan.

By the

High and late medieval theatre, 1050–1500

As the

The Feast of Fools was especially important in the development of comedy. The festival inverted the status of the lesser clergy and allowed them to ridicule their superiors and the routine of church life. Sometimes plays were staged as part of the occasion and a certain amount of burlesque and comedy crept into these performances. Although comic episodes had to truly wait until the separation of drama from the liturgy, the Feast of Fools undoubtedly had a profound effect on the development of comedy in both religious and secular plays.[38]

Performance of religious plays outside of the church began sometime in the 12th century through a traditionally accepted process of merging shorter liturgical dramas into longer plays which were then translated into vernacular and performed by laymen. The Mystery of Adam (1150) gives credence to this theory as its detailed stage direction suggest that it was staged outdoors. A number of other plays from the period survive, including La Seinte Resurrection (Norman), The Play of the Magi Kings (Spanish), and Sponsus (French).

The importance of the

The majority of actors in these plays were drawn from the local population. For example, at Valenciennes in 1547, more than 100 roles were assigned to 72 actors.[40] Plays were staged on pageant wagon stages, which were platforms mounted on wheels used to move scenery. Often providing their own costumes, amateur performers in England were exclusively male, but other countries had female performers. The platform stage, which was an unidentified space and not a specific locale, allowed for abrupt changes in location.

There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by

A significant forerunner of the development of

At the end of the

The end of medieval drama came about due to a number of factors, including the weakening power of the

Italian Commedia dell'arte and Renaissance

The characters of the commedia usually represent fixed social types and

The genesis of commedia may be related to

The

English Elizabethan theatre

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

English Renaissance theatre derived from several medieval theatre traditions, such as, the mystery plays that formed a part of religious festivals in England and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. Other sources include the "morality plays" and the "University drama" that attempted to recreate Athenian tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell'arte, as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court, also contributed to the shaping of public theatre.

Since before the reign of Elizabeth I,

The City of London authorities were generally hostile to public performances, but its hostility was overmatched by the Queen's taste for plays and the Privy Council's support.[59] Theatres sprang up in suburbs, especially in the liberty of Southwark, accessible across the Thames to city dwellers but beyond the authorities' control. The companies maintained the pretence that their public performances were mere rehearsals for the frequent performances before the Queen, but while the latter did grant prestige, the former were the real source of the income for the professional players.

Along with the economics of the profession, the character of the drama changed toward the end of the period. Under Elizabeth, the drama was a unified expression as far as social class was concerned: the Court watched the same plays the commoners saw in the public playhouses. With the development of the private theatres, drama became more oriented toward the tastes and values of an upper-class audience. By the later part of the reign of Charles I, few new plays were being written for the public theatres, which sustained themselves on the accumulated works of the previous decades.[60]

Counter-Reformation theatre

If Protestantism was characterized by an ambivalent relationship to theatricality, Counter-Reformation Catholicism was to use it for explicitly affective and evangelical purposes.[61] The decorative innovations of baroque Catholic churches evolved symbiotically with the increasingly sophisticated art of scenography. Medieval theatrical traditions could be retained and developed in Catholic countries, wherever they were thought to be edifying. Sacre rappresentazioni in Italy, and Corpus Christi celebrations across Europe, are examples of this. Autos sacramentales, the one-act plays at the centre of Corpus Christi celebrations in Spain, gave concrete and triumphal realization to the abstractions of Catholic eucharistic theology, most famously in the hands of Pedro Calderón de la Barca. While the emphasis on predestination in Protestant theology had brought about a new appreciation of fatalism in classical drama, this could be counteracted. The very idea of tragicomedy was controversial because the genre was a post-classical development, but tragicomedies became a popular Counter-Reformation form because they were suited to demonstrating the benign workings of divine providence, and endorsing the concept of free will. Giovanni Battista Guarini’s Il pastor fido (The Faithful Shepherd, written 1580s, published 1602) was the most influential tragicomedy of the period, while Tirso de Molina is especially notable for ingeniously subverting the implications of his tragic plots by means of comic endings. A similar theologically motivated overturning of generic expectation lies behind tragœdiæ sacræ such as Francesco Sforza Pallavicino’s Ermenegildo.[61] This type of sacred tragedy developed from medieval dramatizations of saints’ lives; in them, martyr-protagonists die in a manner both tragic and triumphant. Enhancing Counter-Reformation Catholicism's encouragement of martyr cults, such plays could celebrate contemporary figures like Sir Thomas More — hero of several dramas across Europe — or be used to foment nationalistic sentiment.[61]

Spanish Golden age theatre

During its Golden Age, roughly from 1590 to 1681,[62] Spain saw a monumental increase in the production of live theatre as well as in the importance of theatre within Spanish society. It was an accessible art form for all participants in Renaissance Spain, being both highly sponsored by the aristocratic class and highly attended by the lower classes.[63] The volume and variety of Spanish plays during the Golden Age was unprecedented in the history of world theatre, surpassing, for example, the dramatic production of the English Renaissance by a factor of at least four.[62][63][64] Although this volume has been as much a source of criticism as praise for Spanish Golden Age theatre, for emphasizing quantity before quality,[65] a large number of the 10,000[63] to 30,000[65] plays of this period are still considered masterpieces.[66][67]

Major artists of the period included

The sources of influence for the emerging national theatre of Spain were as diverse as the theatre that nation ended up producing. Storytelling traditions originating in Italian Commedia dell'arte[78] and the uniquely Spanish expression of Western Europe's traveling minstrel entertainments[79][80] contributed a populist influence on the narratives and the music, respectively, of early Spanish theatre. Neo-Aristotelian criticism and liturgical dramas, on the other hand, contributed literary and moralistic perspectives.[81][82] In turn, Spanish Golden Age theatre has dramatically influenced the theatre of later generations in Europe and throughout the world. Spanish drama had an immediate and significant impact on the contemporary developments in English Renaissance theatre.[66] It has also had a lasting impact on theatre throughout the Spanish speaking world.[83] Additionally, a growing number of works are being translated, increasing the reach of Spanish Golden Age theatre and strengthening its reputation among critics and theatre patrons.[84]

French Classical theatre

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

Notable playwrights:

- Pierre Corneille (1606–84)

- Molière (1622–73)

- Jean Racine (1639–99)

Cretan Renaissance theatre

Greek theater was alive and flourishing on the island of Crete. During the Cretan Renaissance two notable Greek playwrights Georgios Chortatzis and Vitsentzos Kornaros were present in the latter part of the 16th century.[85][86]

Restoration comedy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

After public stage performances had been banned for 18 years by the Puritan regime, the re-opening of the theatres in 1660 signalled a renaissance of English drama. With the restoration of the monarch in 1660 came the restoration of and the reopening of the theatre. English comedies written and performed in the

As a reaction to the decadence of Charles II era productions, sentimental comedy grew in popularity. This genre focused on encouraging virtuous behavior by showing middle class characters overcoming a series of moral trials. Playwrights like Colley Cibber and Richard Steele believed that humans were inherently good but capable of being led astray. Through plays such as The Conscious Lovers and Love's Last Shift they strove to appeal to an audience's noble sentiments in order that viewers could be reformed.[87][88]

Restoration spectacular

The Restoration spectacular, or elaborately staged "machine play", hit the

Basically home-grown and with roots in the early 17th-century court masque, though never ashamed of borrowing ideas and stage technology from French opera, the spectaculars are sometimes called "English opera". However, the variety of them is so untidy that most theatre historians despair of defining them as a genre at all.[89] Only a handful of works of this period are usually accorded the term "opera", as the musical dimension of most of them is subordinate to the visual. It was spectacle and scenery that drew in the crowds, as shown by many comments in the diary of the theatre-lover Samuel Pepys.[90] The expense of mounting ever more elaborate scenic productions drove the two competing theatre companies into a dangerous spiral of huge expenditure and correspondingly huge losses or profits. A fiasco such as John Dryden's Albion and Albanius would leave a company in serious debt, while blockbusters like Thomas Shadwell's Psyche or Dryden's King Arthur would put it comfortably in the black for a long time.[91]

Neoclassical theatre

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Neoclassicism was the dominant form of theatre in the 18th century. It demanded decorum and rigorous adherence to the classical unities. Neoclassical theatre as well as the time period is characterized by its grandiosity. The costumes and scenery were intricate and elaborate. The acting is characterized by large gestures and melodrama. Neoclassical theatre encompasses the Restoration, Augustan, and Johnstinian Ages. In one sense, the neo-classical age directly follows the time of the Renaissance.

Theatres of the early 18th century – sexual farces of the Restoration were superseded by politically satirical comedies, 1737 Parliament passed the Stage Licensing Act 1737 which introduced state censorship of public performances and limited the number of theatres in London to two.

Nineteenth-century theatre

Theatre in the 19th century is divided into two parts: early and late. The early period was dominated by melodrama and Romanticism.

Beginning in France, melodrama became the most popular theatrical form.

In Germany, there was a trend toward historical accuracy in costumes and settings, a revolution in theatre architecture, and the introduction of the theatrical form of German Romanticism. Influenced by trends in 19th-century philosophy and the visual arts, German writers were increasingly fascinated with their Teutonic past and had a growing sense of nationalism. The plays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and other Sturm und Drang playwrights inspired a growing faith in feeling and instinct as guides to moral behavior.

In Britain, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron were the most important dramatists of their time although Shelley's plays were not performed until later in the century. In the minor theatres, burletta and melodrama were the most popular. Kotzebue's plays were translated into English and Thomas Holcroft's A Tale of Mystery was the first of many English melodramas. Pierce Egan, Douglas William Jerrold, Edward Fitzball, and John Baldwin Buckstone initiated a trend towards more contemporary and rural stories in preference to the usual historical or fantastical melodramas. James Sheridan Knowles and Edward Bulwer-Lytton established a "gentlemanly" drama that began to re-establish the former prestige of the theatre with the aristocracy.[93]

The later period of the 19th century saw the rise of two conflicting types of drama:

Realism began earlier in the 19th century in Russia than elsewhere in Europe and took a more uncompromising form.

The most important theatrical force in later 19th-century Germany was that of

In Britain, melodramas, light comedies, operas, Shakespeare and classic English drama,

While their work paved the way, the development of more significant drama owes itself most to the playwright

After Ibsen, British theatre experienced revitalization with the work of

Twentieth-century theatre

While much

The term

Other key figures of 20th-century theatre include: Antonin Artaud, August Strindberg, Anton Chekhov, Max Reinhardt, Frank Wedekind, Maurice Maeterlinck, Federico García Lorca, Eugene O'Neill, Luigi Pirandello, George Bernard Shaw, Gertrude Stein, Ernst Toller, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Heiner Müller, and Caryl Churchill.

A number of aesthetic movements continued or emerged in the 20th century, including:

- Naturalism

- Realism

- Dadaism

- Expressionism

- Surrealism and the Theatre of Cruelty

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Postmodernism

- Agitprop

After the great popularity of the British

American theatre

1752 to 1895 Romanticism

Throughout most of history, English

As the country expanded so did theatre; following the

1895 to 1945 Realism

In this era of theatre, the moral hero shifts to the modern man who is a product of his environment.[112] This major shift is due in part to the civil war because America was now stained with its own blood, having lost its innocence.[113]

1945 to 1990

During this period of theatre, Hollywood emerged and threatened American theatre.[114] However theatre during this time didn't decline but in fact was renowned and noticed worldwide.[114] Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller achieved worldwide fame during this period.

African theatre

Egyptian theatre

Ancient Egyptian quasi-theatrical events

The earliest recorded quasi-theatrical event dates back to 2000 BC with the "passion plays" of Ancient Egypt. The story of the god Osiris was performed annually at festivals throughout the civilization.[115]

Modern Egyptian theater

In the modern era, the art of theater was evolved in the second half of the nineteenth century through interaction with Europe. As well as the development of popular theatrical forms that Egypt knew thousands of years before this date.[116][117][118]

The beginning was by

More than 350 plays were presented in the so-called halls theater in the 1930s and 1940s, co-presented by

After the

Among the Egyptian playwrights whose works were presented on stage are Amin Sedky, Badi’ Khairy, Abu Al-Saud Al-Ebiary, and Tawfiq Al-Hakim. Most of the world's playwrights whose works were presented on the stage are Molière, Pierre Corneille and William Shakespeare.[125][126]

The women's imprint was clear in the history of Egyptian theater, which

In 2020, the Egyptian Minister of Culture, Dr. Ines Abdel-Dayem dedicates the next session of the National Festival of Egyptian Theater to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the modern Egyptian theater. It will review the findings of the research team, consisting of Amr Dawara, the theater memory guard, who started since 1993 to prepare the largest Egyptian theater encyclopedia that includes all the details of professional theatrical performances during fifteen decades, starting from 1870 by Yacub Sanu until 2019, during which the number of performances reached 6300 professional works, which were presented to the public for a fee at the box office. And addressed the book body to print the encyclopedia. And that encyclopedia will help the reader and researcher to know the masterpieces and creations of Egyptian theater throughout its history.[127][128][122]

West African theatre

Ghanaian theatre

Modern theatre in Ghana emerged in the early 20th century.[129] It emerged first as literary comment on the colonization of Africa by Europe.[129] Among the earliest work in which this can be seen is The Blinkards written by Kobina Sekyi in 1915. The Blinkards is a blatant satire about the Africans who embraced the European culture that was brought to them. In it Sekyi demeans three groups of individuals: anyone European, anyone who imitates the Europeans, and the rich African cocoa farmer. This sudden rebellion though was just the beginning spark of Ghanaian literary theatre.[129]

A play that has similarity in its satirical view is Anowa. Written by Ghanaian author Ama Ata Aidoo, it begins with its eponymous heroine Anowa rejecting her many arranged suitors' marriage proposals. She insists on making her own decisions as to whom she is going to marry. The play stresses the need for gender equality, and respect for women.[129] This ideal of independence, as well as equality leads Anowa down a winding path of both happiness and misery. Anowa chooses a man of her own to marry. Anowa supports her husband Kofi both physically and emotionally. Through her support Kofi does prosper in wealth, but becomes poor as a spiritual being. Through his accumulation of wealth Kofi loses himself in it. His once happy marriage with Anowa becomes changed when he begins to hire slaves rather than doing any labor himself. This to Anowa does not make sense because it makes Kofi no better than the European colonists whom she detests for the way that she feels they have used the people of Africa. Their marriage is childless, which is presumed to have been caused by a ritual that Kofi has done trading his manhood for wealth. Anowa's viewing Kofi's slave-gotten wealth and inability to have a child leads to her committing suicide.[129] The name Anowa means "Superior moral force" while Kofi's means only "Born on Friday". This difference in even the basis of their names seems to implicate the moral superiority of women in a male run society.[129]

Another play of significance is The Marriage of Anansewa, written in 1975 by

Yoruba theatre

In his pioneering study of

The

"Total theatre" also developed in Nigeria in the 1950s. It utilised non-Naturalistic techniques, surrealistic physical imagery, and exercised a flexible use of language. Playwrights writing in the mid-1970s made use of some of these techniques, but articulated them with "a radical appreciation of the problems of society."[136]

Traditional performance modes have strongly influenced the major figures in contemporary Nigerian theatre. The work of Hubert Ogunde (sometimes referred to as the "father of contemporary Yoruban theatre") was informed by the Aláàrìnjó tradition and Egungun masquerades.[137] Wole Soyinka, who is "generally recognized as Africa's greatest living playwright", gives the divinity Ogun a complex metaphysical significance in his work.[138] In his essay "The Fourth Stage" (1973),[139] Soyinka contrasts Yoruba drama with classical Athenian drama, relating both to the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's analysis of the latter in The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Ogun, he argues, is "a totality of the Dionysian, Apollonian and Promethean virtues."[140]

The proponents of the travelling theatre in Nigeria include Duro Ladipo and Moses Olaiya (a popular comic act). These practitioners contributed much to the field of African theatre during the period of mixture and experimentation of the indigenous with the Western theatre.

African Diaspora theatre

African-American theatre

The history of African-American theatre has a dual origin. The first is rooted in local theatre where African Americans performed in cabins and parks. Their performances (folk tales, songs, music, and dance) were rooted in the African culture before being influenced by the American environment.

Asian theatre

Indian theatre

Overview of Indian theatre

The earliest form of

Sanskrit theatre

The earliest-surviving fragments of Sanskrit drama date from the 1st century.

However, although there are no surviving fragments of any drama prior to this date, it is possible that early Buddhist literature provides the earliest evidence for the existence of Indian theatre. The

The major source of evidence for Sanskrit theatre is

Under the patronage of royal courts, performers belonged to professional companies that were directed by a stage manager (sutradhara), who may also have acted.[153] This task was thought of as being analogous to that of a puppeteer—the literal meaning of "sutradhara" is "holder of the strings or threads".[150] The performers were trained rigorously in vocal and physical technique.[154] There were no prohibitions against female performers; companies were all-male, all-female, and of mixed gender. Certain sentiments were considered inappropriate for men to enact, however, and were thought better suited to women. Some performers played character their own age, while others played those different from their own (whether younger or older). Of all the elements of theatre, the Treatise gives most attention to acting (abhinaya), which consists of two styles: realistic (lokadharmi) and conventional (natyadharmi), though the major focus is on the latter.[155]

Its drama is regarded as the highest achievement of

The next great Indian dramatist was

Traditional Indian theatre

Kathakali

Kathakali is a highly stylised classical Indian dance-drama noted for the attractive make-up of characters, elaborate costumes, detailed gestures, and well-defined body movements presented in tune with the anchor playback music and complementary percussion. It originated in the country's present-day state of Kerala during the 17th century[157] and has developed over the years with improved looks, refined gestures and added themes besides more ornate singing and precise drumming.

Modern Indian theatre

Rabindranath Tagore was a pioneering modern playwright who wrote plays noted for their exploration and questioning of nationalism, identity, spiritualism and material greed.[158] His plays are written in Bengali and include Chitra (Chitrangada, 1892), The King of the Dark Chamber (Raja, 1910), The Post Office (Dakghar, 1913), and Red Oleander (Raktakarabi, 1924).[158]

Another pioneering playwright in

Chinese theatre

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Shang theatre

There are references to theatrical entertainments in China as early as 1500 BC during the Shang dynasty; they often involved music, clowning and acrobatic displays.

Han and Tang theatre

During the Han dynasty, shadow puppetry first emerged as a recognized form of theatre in China. There were two distinct forms of shadow puppetry, Cantonese southern and Pekingese northern. The two styles were differentiated by the method of making the puppets and the positioning of the rods on the puppets, as opposed to the type of play performed by the puppets. Both styles generally performed plays depicting great adventure and fantasy, rarely was this very stylized form of theatre used for political propaganda. Cantonese shadow puppets were the larger of the two. They were built using thick leather which created more substantial shadows. Symbolic color was also very prevalent; a black face represented honesty, a red one bravery. The rods used to control Cantonese puppets were attached perpendicular to the puppets' heads. Thus, they were not seen by the audience when the shadow was created. Pekingese puppets were more delicate and smaller. They were created out of thin, translucent leather usually taken from the belly of a donkey. They were painted with vibrant paints, thus they cast a very colorful shadow. The thin rods which controlled their movements were attached to a leather collar at the neck of the puppet. The rods ran parallel to the bodies of the puppet then turned at a ninety degree angle to connect to the neck. While these rods were visible when the shadow was cast, they laid outside the shadow of the puppet; thus they did not interfere with the appearance of the figure. The rods attached at the necks to facilitate the use of multiple heads with one body. When the heads were not being used, they were stored in a muslin book or fabric lined box. The heads were always removed at night. This was in keeping with the old superstition that if left intact, the puppets would come to life at night. Some puppeteers went so far as to store the heads in one book and the bodies in another, to further reduce the possibility of reanimating puppets. Shadow puppetry is said to have reached its highest point of artistic development in the 11th century before becoming a tool of the government.

The Tang dynasty is sometimes known as 'The Age of 1000 Entertainments'. During this era,

Song and Yuan theatre

In the

Yuan drama spread across China and diversified into numerous regional forms, the best known of which is Beijing Opera, which is still popular today.

Indonesian theatre

Indonesian theatre has become an important part of local culture, theater performances in

Khmer theatre

In Cambodia, at the ancient capital Angkor Wat, stories from the Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata have been carved on the walls of temples and palaces.

Thai theatre

In Thailand, it has been a tradition from the Middle Ages to stage plays based on plots drawn from Indian epics. In particular, the theatrical version of Thailand's national epic Ramakien, a version of the Indian Ramayana, remains popular in Thailand even today.

Philippine theatre

During the 333-year reign of the Spanish government, they introduced into the islands the Catholic religion and the Spanish way of life, which gradually merged with the indigenous culture to form the “lowland folk culture” now shared by the major ethnolinguistic groups. Today, the dramatic forms introduced or influenced by Spain continue to live in rural areas all over the archipelago. These forms include the komedya, the playlets, the sinakulo, the sarswela, and the drama. In recent years, some of these forms have been revitalized to make them more responsive to the conditions and needs of a developing nation.

Japanese theatre

Noh

During the 14th century, there were small companies of actors in Japan who performed short, sometimes vulgar comedies. A director of one of these companies, Kan'ami (1333–1384), had a son, Zeami Motokiyo (1363–1443) who was considered one of the finest child actors in Japan. When Kan'ami's company performed for Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), the Shōgun of Japan, he implored Zeami to have a court education for his arts. After Zeami succeeded his father, he continued to perform and adapt his style into what is today Noh. A mixture of pantomime and vocal acrobatics, this style has fascinated the Japanese for hundreds of years.

Bunraku

Japan, after a long period of civil wars and political disarray, was unified and at peace primarily due to shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616). However, alarmed at increasing Christian growth, he cut off contact from Japan to Europe and China and outlawed Christianity. When peace did come, a flourish of cultural influence and growing merchant class demanded its own entertainment. The first form of theatre to flourish was Ningyō jōruri (commonly referred to as Bunraku). The founder of and main contributor to Ningyō jōruri, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1725), turned his form of theatre into a true art form. Ningyō jōruri is a highly stylized form of theatre using puppets, today about 1/3d the size of a human. The men who control the puppets train their entire lives to become master puppeteers, when they can then operate the puppet's head and right arm and choose to show their faces during the performance. The other puppeteers, controlling the less important limbs of the puppet, cover themselves and their faces in a black suit, to imply their invisibility. The dialogue is handled by a single person, who uses varied tones of voice and speaking manners to simulate different characters. Chikamatsu wrote thousands of plays during his career, most of which are still used today. They wore masks instead of elaborate makeup. Masks define their gender, personality, and moods the actor is in.

Kabuki

Kabuki began shortly after Bunraku, legend has it by an actress named Okuni, who lived around the end of the 16th century. Most of Kabuki's material came from Nõ and Bunraku, and its erratic dance-type movements are also an effect of Bunraku. However, Kabuki is less formal and more distant than Nõ, yet very popular among the Japanese public. Actors are trained in many varied things including dancing, singing, pantomime, and even acrobatics. Kabuki was first performed by young girls, then by young boys, and by the end of the 16th century, Kabuki companies consisted of all men. The men who portrayed women on stage were specifically trained to elicit the essence of a woman in their subtle movements and gestures.

Butoh

Butoh is the collective name for a diverse range of activities, techniques and motivations for dance, performance, or movement inspired by the Ankoku-Butoh (暗黒舞踏, ankoku butō) movement. It typically involves playful and grotesque imagery, taboo topics, extreme or absurd environments, and is traditionally performed in white body makeup with slow hyper-controlled motion, with or without an audience. There is no set style, and it may be purely conceptual with no movement at all. Its origins have been attributed to Japanese dance legends Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. Butoh appeared first in Japan following World War II and specifically after student riots. The roles of authority were now subject to challenge and subversion. It also appeared as a reaction against the contemporary dance scene in Japan, which Hijikata felt was based on the one hand on imitating the West and on the other on imitating the Noh. He critiqued the current state of dance as overly superficial.

Turkish theatre

1st mention of theatre plays in

Persian theatre

Medieval Islamic theatre

The most popular forms of theatre in the

See also

- Antitheatricality

- The Cambridge History of British Theatre

- Development of musical theatre

- History of art

- History of dance

- History of figure skating

- History of film

- History of literature

- History of opera

- History of professional wrestling

- History of television

- Play (theatre)

- Radio drama

Notes

- ^ Goldhill argues that although activities that form "an integral part of the exercise of citizenship" (such as when "the Athenian citizen speaks in the Assembly, exercises in the gymnasium, sings at the symposium, or courts a boy") each have their "own regime of display and regulation," nevertheless the term "performance" provides "a useful heuristic category to explore the connections and overlaps between these different areas of activity" (1999, 1).

- ^ Taxidou says that "most scholars now call 'Greek' tragedy 'Athenian' tragedy, which is historically correct" (2004, 104).

- ^ Cartledge writes that although Athenians of the 4th century judged Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides "as the nonpareils of the genre, and regularly honoured their plays with revivals, tragedy itself was not merely a 5th-century phenomenon, the product of a short-lived golden age. If not attaining the quality and stature of the fifth-century 'classics', original tragedies nonetheless continued to be written and produced and competed with in large numbers throughout the remaining life of the democracy—and beyond it" (1997, 33).

- ^ We have seven by Aeschylus, seven by Sophocles, and eighteen by Euripides. In addition, we also have the Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides. Some critics since the 17th century have argued that one of the tragedies that the classical tradition gives as Euripides'—Rhesus—is a 4th-century play by an unknown author; modern scholarship agrees with the classical authorities and ascribes the play to Euripides; see Walton (1997, viii, xix). (This uncertainty accounts for Brockett and Hildy's figure of 31 tragedies rather than 32.)

- ^ The theory that Prometheus Bound was not written by Aeschylus adds a fourth, anonymous playwright to those whose work survives.

- ^ Exceptions to this pattern were made, as with Euripides' Alcestis in 438 BC. There were also separate competitions at the City Dionysia for the performance of dithyrambs and, after 488–7 BC, comedies.

- temple near the theatre of Dionysus and taken to a temple on the road to Eleutherae. That evening, after sacrifice and hymns, a torchlight procession carried the statue back to the temple, a symbolic re-creation of the god's arrival into Athens, as well as a reminder of the inclusion of the Boeotian town into Attica. As the name Eleutherae is extremely close to eleutheria, 'freedom', Athenians probably felt that the new cult was particularly appropriate for celebrating their own political liberation and democratic reforms" (1992, 15).

- ^ Jean-Pierre Vernant argues that in The Persians Aeschylus substitutes for the usual temporal distance between the audience and the age of heroes a spatial distance between the Western audience and the Eastern Persian culture. This substitution, he suggests, produces a similar effect: "The 'historic' events evoked by the chorus, recounted by the messenger and interpreted by Darius' ghost are presented on stage in a legendary atmosphere. The light that the tragedy sheds upon them is not that in which the political happenings of the day are normally seen; it reaches the Athenian theater refracted from a distant world of elsewhere, making what is absent seem present and visible on the stage"; Vernant and Vidal-Naquet (1988, 245).

- ^ For more information on the ancient Roman dramatists, see the articles categorised under "Ancient Roman dramatists and playwrights" in Wikipedia.

References

- ^ Banham (1995), Brockett and Hildy (2003), and Goldhill (1997, 54).

- ^ a b Cohen and Sherman (2020, ch. 7).

- ^ Aristotle, Poetics VI, 2.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (1968; 10th ed. 2010), History of the Theater.

- ^ Davidson (2005, 197) and Taplin (2003, 10).

- ^ Cartledge (1997, 3, 6), Goldhill (1997, 54) and (1999, 20-xx), and Rehm (1992. 3).

- ^ Pelling (2005, 83).

- ^ Goldhill (1999, 25) and Pelling (2005, 83–84).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–19).

- ^ Brown (1995, 441), Cartledge (1997, 3–5), Goldhill (1997, 54), Ley (2007, 206), and Styan (2000, 140).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 32–33), Brown (1995, 444), and Cartledge (1997, 3–5).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15) and Kovacs (2005, 379).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 13–15) and Brown (1995, 441–447).

- ^ Brown (1995, 442) and Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–17).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 13, 15) and Brown (1995, 442).

- ^ Brown (1995, 442).

- ^ Brown (1995, 442) and Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–16).

- ^ Aristotle, Poetics: "Comedy is, as we said, a representation of people who are rather inferior—not, however, with respect to every [kind of] vice, but the laughable is [only] a part of what is ugly. For the laughable is a sort of error and ugliness that is not painful and destructive, just as, evidently, a laughable mask is something ugly and distorted without pain" (1449a 30–35); see Janko (1987, 6).

- ^ Beacham (1996, 2).

- ^ Beacham (1996, 3).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 43).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 36, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 46–47).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47–48).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48–49).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 50).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49–50).

- Pat Easterling and Edith Hall, eds., Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession Archived 2020-05-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 70)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 75)

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 76)

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 77)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 78)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 81)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 86)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 95)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 96)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 99)

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 101–103)

- ^ History of theatre at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Lea, Kathleen (1962). Italian Popular Comedy: A Study In The Commedia Dell'Arte, 1560–1620 With Special Reference to the English State. New York: Russell & Russell INC. p. 3.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Wilson, Matthew R. "A History of Commedia dell'arte". Faction of Fools. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-04769-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0486216799.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-74506-2.

- ^ "Faction Of Fools". Archived from the original on 2017-03-13. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-325-00346-7.

- ISBN 978-0-933826-69-4.

- ^ Broadbent, R.J. (1901). A History Of Pantomime. New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 62.

- ^ "Faction of Fools | A History of Commedia dell'Arte". www.factionoffools.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ^ Maurice, Sand (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc. p. 135.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Nicoll, Allardyce (1963). The World of Harlequin: A Critical Study of the Commedia dell'Arte. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 9.[ISBN unspecified]

- ISBN 91-7324-602-6

- ^ a b c Mortimer (2012, 352).

- ^ Mortimer (2012, 353).

- ^ Gurr (1992, 12–18).

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-860174-6. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ JSTOR 30228091.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85566-140-0. Archivedfrom the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Compleat Catalogue of Plays that Were Ever Printed in the English Language. W. Mears. 1719. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Introduction to Theatre – Spanish Renaissance Theatre". Novaonline.nvcc.edu. 2007-11-16. Archived from the original on 2021-01-16. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ a b "Golden Age". Comedia.denison.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-12-17. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- JSTOR 470268.

- ^ Ernst Honigmann. "Cambridge Collections Online : Shakespeare's life". Cco.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ISBN 978-0-8387-5372-9. Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Calderon and Lope de Vega". Theatredatabase.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- JSTOR 27922855.

- JSTOR 3204377.

- ISBN 978-0-8057-6166-5. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- JSTOR 471618.

- JSTOR 333062.

- ISBN 978-0-07-079169-5. Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- JSTOR 27763975.

- ^ "Background to Spanish Drama – Medieval to Renascence Drama > Spanish Golden Age Drama – Drama Courses". Courses in Drama. 2007-12-23. Archived from the original on 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ISBN 978-1-55753-441-5. Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- JSTOR 3128021.

- ^ "Share Documents and Files Online | Microsoft Office Live". Westerntheatrehistory.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ "Hispanic, Portuguese & Latin American Studies – HISP20048 The Theatre of the Spanish Golden Age". Bristol University. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ISBN 978-1-85459-249-1. Archivedfrom the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- S2CID 161917109.

- ISBN 0-521-29978-0.

- ^ "Cretan – Lang Up". Archived from the original on 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- ^ Campbell, William. "Sentimental Comedy in England and on the Continent". The Cambridge History of English and American Literature. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ISBN 978-0205024018.

- ^ Hume (1976, 205).

- ^ Hume (1976, 206–209).

- ^ Milhous (1979, 47–48).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 277).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 297–298).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 370).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 370, 372) and Benedetti (2005, 100) and (1999, 14–17).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 357–359).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 362–363).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 326–327).

- In Town (1892). See, e.g., Charlton, Fraser. "What are EdMusComs?" Archived 2007-12-08 at the Wayback MachineFrasrWeb 2007, accessed May 12, 2011

- ^ Milling and Ley (2001, vi, 173) and Pavis (1998, 280). German: Theaterpraktiker, French: praticien, Spanish: teatrista.

- ^ Pavis (1998, 392).

- ^ McCullough (1996, 15–36) and Milling and Ley (2001, vii, 175).

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Brockett, Oscar G.; Hildy, Franklin J. (1999). History of the Theatre. Allyn and Bacon. p. 692.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1998). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume One: Beginnings to 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1999). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume Two: 1870–1945. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (1999). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume Two: 1870–1945. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (2000). The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Volume Three: Post-World War II to The 1990s. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Egyptian "Passion" Plays". Theatrehistory.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ "المسرح في مصر". State Information Service (Egypt) (in Arabic). 2009-09-30. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ Aḥmad, Muḥammad Fattūḥ; فتوح, احمد، محمد (1978). في المسرح المصري المعاصر :: دراسة في النص المسرحي / (in Arabic). مكتبة الشباب،. Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ISBN 978-1-4773-1918-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ حسين, عامر، سامى منير (1978). المسرح المصرى بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية بين الفن والنقد السياسى والإجتماعي (in Arabic). الهيئة المصرية العامة للكتاب ،. Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ "مراحل نشأة المسرح في مصر". www.albawabhnews.com. 2019-02-20. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ISBN 978-0-8156-3163-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ a b "المسرح المصرى "150 عاما " من النضال والتألق". الأهرام اليومي (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "From Comedy to Tragedy: A Brief History of the Evolution of Theatre in Egypt | Egyptian Streets". 2020-10-07. Archived from the original on 2022-01-05. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "History of Egyptian Art". www.cairo.gov.eg. Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- from the original on 2022-04-24. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "Dilemmas of Egypt's National Theatre - Stage & Street - Arts & Culture". Ahram Online. Archived from the original on 2022-04-24. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ Zohdi, Salma S. (2016). Egyptian theatre and its impact on society: History, deterioration, and path for rehabilitation (PDF) (MFA). Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ S2CID 142717092.

- ^ Adedeji (1969, 60).

- ^ Noret (2008, 26).

- ^ Gilbert, Helen (May 31, 2001). Postcolonial Plays:An Anthology. Routledge.

- ^ Banham, Hill, and Woodyard (2005, 88).

- ^ Banham, Hill, and Woodyard (2005, 88–89).

- ISBN 1-56159-239-0

- ^ Banham, Hill, and Woodyard (2005, 70).

- ^ Banham, Hill, and Woodyard (2005, 76).

- ^ Banham, Hill, and Woodyard (2005, 69).

- ^ Soyinka (1973, 120).

- ^ Soyinka (1973).

- ISBN 978-0-521-44522-1.

- ^ Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 12).

- ^ Brandon (1997, 70) and Richmond (1995, 516).

- ISBN 978-81-7017-221-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-18. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Brandon (1997, 72) and Richmond (1995, 516).

- ^ Brandon (1997, 72), Richmond (1995, 516), and Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 12).

- ^ Richmond (1995, 516) and Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 13).

- ^ Brandon (1981, xvii) and Richmond (1995, 516–517).

- ^ a b Richmond (1995, 516).

- ^ a b c d Richmond (1995, 517).

- ^ Rachel Van M. Baumer and James R. Brandon (ed.), Sanskrit Drama in Performance Archived 2021-02-17 at the Wayback Machine (University of Hawaii Press, 1981), pp.11

- ^ Sanskrit Drama in Performance Archived 2021-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, p.11

- ^ Brandon (1981, xvii) and Richmond (1995, 517).

- ^ Richmond (1995, 518).

- ^ Richmond (1995, 518). The literal meaning of abhinaya is "to carry forwards".

- ^ a b Brandon (1981, xvii).

- ^ Zarrilli (1984).

- ^ a b Banham (1995, 1051).

- JSTOR 1124435.

- ISBN 978-0-415-26087-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ "PENGETAHUAN TEATER" (PDF), Kemdikbud, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-03, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ISBN 0-06-051605-4, 2003, pp. 141 - 142

- ^ Moreh (1986, 565–601).

Sources

- Adejeji, Joel. 1969. "Traditional Yoruba Theatre." African Arts 3.1 (Spring): 60–63. JSTOR 3334461

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1995. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Rev. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-43437-9.

- Banham, Martin, Errol Hill, and George Woodyard, eds. 2005. The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-61207-4.

- Baumer, Rachel Van M., and James R. Brandon, eds. 1981. Sanskrit Theatre in Performance. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1993. ISBN 978-81-208-0772-3.

- Beacham, Richard C. 1996. The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. ISBN 978-0-674-77914-3.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1.

- ––. 2005. The Art of the Actor: The Essential History of Acting, From Classical Times to the Present Day. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77336-1.

- Brandon, James R. 1981. Introduction. In Baumer and Brandon (1981, xvii–xx).

- ––, ed. 1997. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. 2nd, rev. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

- Brinton, Crane, John B Christopher, and Robert Lee Wolff. 1981. Civilization in the West: Part 1 Prehistory to 1715. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-134924-7.

- Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. 2003. History of the Theatre. Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

- Brown, Andrew. 1995. "Ancient Greece." In Banham (1995, 441–447).

- Cartledge, Paul. 1997. "'Deep Plays': Theatre as Process in Greek Civic Life." In Easterling (1997, 3–35).

- Cohen, Robert, and Donovan Sherman. 2020. "Chapter 7: Theatre Traditions." Theatre: Brief Edition. Twelfth ed. New York, NY. OCLC 1073038874.

- Counsell, Colin. 1996. Signs of Performance: An Introduction to Twentieth-Century Theatre. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10643-6.

- Davidson, John. 2005. "Theatrical Production." In Gregory (2005, 194–211).

- Duffy, Eamon. 1992. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580. New Haven: Yale UP. ISBN 978-0-300-06076-8.

- ISBN 0-521-42351-1.

- Falossi, F. and Mastropasqua, F. "L'Incanto Della Maschera." Vol. 1 Prinp Editore, Torino:2014 www.prinp.com ISBN 978-88-97677-50-5

- Finley, Moses I. 1991. The Ancient Greeks: An Introduction to their Life and Thought. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013707-1.

- Goldhill, Simon. 1997. "The Audience of Athenian Tragedy." In Easterling (1997, 54–68).

- ––. 1999. "Programme Notes." In Goldhill and Osborne (2004, 1–29).

- ––. 2008. "Generalizing About Tragedy." In Felski (2008b, 45–65).

- Goldhill, Simon, and Robin Osborne, eds. 2004. Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy. New edition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-60431-4.

- Gregory, Justina, ed. 2005. A Companion to Greek Tragedy. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World ser. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-7549-4.

- Grimsted, David. 1968. Melodrama Unveiled: American Theatre and Culture, 1800–50. Chicago: U of Chicago P. ISBN 978-0-226-30901-9.

- ISBN 0-521-42240-X.

- Hume, Robert D. 1976. The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811799-5.

- Janko, Richard, trans. 1987. Poetics with Tractatus Coislinianus, Reconstruction of Poetics II and the Fragments of the On Poets. By ISBN 0-87220-033-7.

- Kovacs, David. 2005. "Text and Transmission." In Gregory (2005, 379–393).

- Ley, Graham. 2006. A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater. Rev. ed. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P. ISBN 978-0-226-47761-9.

- –. 2007. The Theatricality of Greek Tragedy: Playing Space and Chorus. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P. ISBN 978-0-226-47757-2.

- McCullough, Christopher, ed. 1998. Theatre Praxis: Teaching Drama Through Practice. New Directions in Theatre Ser. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-21611-5.

- ––. 1996. Theatre and Europe (1957–1996). Intellect European Studies ser. Exeter: Intellect. ISBN 978-1-871516-82-1.

- McDonald, Marianne. 2003. The Living Art of Greek Tragedy. Bloomington: Indiana UP. ISBN 978-0-253-21597-0.

- McKay, John P., Bennett D. Hill, and John Buckler. 1996. A History of World Societies. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-75377-4.

- Milhous, Judith 1979. Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln's Inn Fields 1695–1708. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois UP. ISBN 978-0-8093-0906-1.

- Milling, Jane, and Graham Ley. 2001. Modern Theories of Performance: From Stanislavski to Boal. Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-77542-4.

- Moreh, Shmuel. 1986. "Live Theater in Medieval Islam." In Studies in Islamic History and Civilization in Honour of Professor David Ayalon. Ed. ISBN 978-965-264-014-7.

- Mortimer, Ian. 2012. "The Time-Traveller's Guide To Elizabethan England." London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-114-7.

- Munby, Julian, Richard Barber, and Richard Brown. 2007. Edward III's Round Table at Windsor: The House of the Round Table and the Windsor Festival of 1344. Arthurian Studies ser. Woodbridge: Boydell P. ISBN 978-1-84383-391-8.

- Noret, Joël. 2008. "Between Authenticity and Nostalgia: The Making of a Yoruba Tradition in Southern Benin." African Arts 41.4 (Winter): 26–31.

- Pavis, Patrice. 1998. Dictionary of the Theatre: Terms, Concepts, and Analysis. Trans. Christine Shantz. Toronto and Buffalo: U of Toronto P. ISBN 978-0-8020-8163-6.

- Pelling, Christopher. 2005. "Tragedy, Rhetoric, and Performance Culture." In Gregory (2005, 83–102).

- ISBN 0-415-11894-8.

- Richmond, Farley. 1995. "India." In Banham (1995, 516–525).

- Richmond, Farley P., Darius L. Swann, and Phillip B. Zarrilli, eds. 1993. Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. U of Hawaii P. ISBN 978-0-8248-1322-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-6280-2.

- Styan, J. L. 2000. Drama: A Guide to the Study of Plays. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-4489-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-1987-0.

- Taxidou, Olga. 2004. Tragedy, Modernity and Mourning. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP. ISBN 0-7486-1987-9.

- Thornbrough, Emma Lou. 1996. The Ancient Greeks. Acton, MA: Copley. ISBN 978-0-87411-860-5.

- Tsitsiridis, Stavros, "Greek Mime in the Roman Empire (P.Oxy. 413: Charition and Moicheutria", Logeion 1 (2011) 184–232.

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre, and Pierre Vidal-Naquet. 1988. Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece. Trans. Janet Lloyd. New York: Zone Books, 1990.

- Walton, J. Michael. 1997. Introduction. In Plays VI. By Euripides. Methuen Classical Greek Dramatists ser. London: Methuen. vii–xxii. ISBN 0-413-71650-3.

- ISBN 0-7011-1260-3.

- Zarrilli, Phillip B. 1984. The Kathakali Complex: Actor, Performance and Structure. [S.l.]: South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0-391-03029-9.

External links

- Theatre Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, with information and archive material

- University of Bristol Theatre Collection, University of Bristol

- Music Hall and Theatre History – an archive of historical information and material on British Theatre and Music Hall buildings.

- Long running plays (over 400 performances) on Broadway, Off-Broadway, London, Toronto, Melbourne, Paris, Vienna, and Berlin

- APGRD Database (Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama), University of Oxford, ed. Amanda Wrigley

- Women's Theatre History: Online Bibliography and Searchable Database Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine at Langara College