History of opera

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2023) |

The history of opera has a relatively short duration within the context of the history of music in general: it appeared in 1597, when the first opera, Dafne, by Jacopo Peri, was created. Since then it has developed parallel to the various musical currents that have followed one another over time up to the present day, generally linked to the current concept of classical music.

Opera (from the Latin opera, plural of opus, "work") is a musical genre that combines symphonic music, usually performed by an orchestra, and a written dramatic text—expressed in the form of a

As a multidisciplinary genre, opera brings together music, singing, dance, theater, scenography, performance, costumes, makeup, hairdressing, and other artistic disciplines. It is therefore a work of collective creation, which essentially starts from a librettist and a composer, and where the vocal performers have a primordial role, but where the musicians and the conductor, the dancers, the creators of the sets and costumes, and many other figures are equally essential. On the other hand, it is a social event, so it has no reason to exist without an audience to witness the show. For this very reason, it has been over time a reflection of the various currents of thought, political and philosophical, religious and moral, aesthetic and cultural, peculiar to the society where the plays were produced.[3]

Opera was born at the end of the 16th century, as an initiative of a circle of scholars (the , giving structure to the modern opera.

The subsequent evolution of opera has run parallel to the various musical currents that have followed one another over time: between the 17th century and the first half of the 18th it was framed by the

During the course of history, within opera there have been differences of opinion as to which of its components was more important, the music or the text, or even whether the importance lay in the singing and virtuosity of the performers, a phenomenon that gave rise to

Background

Opera has its roots in the various forms of sung or musical theater that have been produced throughout history all over the world. Dramatic representation as well as singing, music, dance and other artistic manifestations are forms of expression consubstantial to human beings, practiced since

During the Middle Ages, music and theater were also closely related. They were works of religious character, of two types: liturgical dramas to be performed in the churches, celebrated in Latin; and the so-called "mystery play", theatrical pieces of popular character that were represented in the porches of the churches, in vernacular language. These plays alternated spoken and sung parts, generally in choir, and were accompanied by instrumental music and, sometimes, popular dances.[7]

In Japan, the

In the

Origins

At the end of the 16th century, in Florence, a circle of scholars sponsored by Count Giovanni de' Bardi created a society called Florentine Camerata, aimed to study and critical discussion of the arts, especially drama and music.[11] One of its scholars was Vincenzo Galilei —father of the scientist Galileo— a celebrated Hellenist and musicologist, author of a method of tablature for lute and composer of madrigals and recitatives.[12] In the course of their studies of Ancient Greek theater they found that in Greek theatrical performances the text was sung to individual voices. This idea struck them, since nothing like it existed at the time, at a time when almost all sung music was choral (polyphony) and, in cases of individual voices, occurred only in the religious sphere. They then had the idea of setting dramatic texts of a profane nature to music, which germinated in opera (opera in musica was the name given to it by the Camerata).[13][note 1] Galilei was the main advocate of a single melodic line —the monody— as opposed to polyphony, which he considered to generate an incoherent musical discourse, a theory he expounded in Dialogo della musica antica et della moderna (1581). Another of the Camerata's scholars, Girolamo Mei, who was the one who mainly investigated Greek theater, pointed out the emotional affect that individual singing generated in the audience in Greek theatrical performances (De modis musicis antiquorum, 1573).[14]

Thus, one of the members of the Camerata, the composer

Another member of the Camerata, Giulio Caccini, composed in 1602 Euridice, with the same libretto by Rinuccini as his namesake of two years earlier, with prologue and three acts.[17] He was the author of the first theoretical treatise on the new genre, Le nuove musiche (1602).[18] His daughter, Francesca Caccini, was a singer and composer, the first woman to compose an opera: La liberazione di Ruggiero dall'isola d'Alcina (1625).[19]

One of the main novelties of this new form of artistic expression was its secularism, at a time when artistic and musical production was mostly of a religious nature. Another was the appearance of monody, the singing of a single voice, as opposed to medieval and Renaissance polyphony; it was a vocal line accompanied by a basso continuo of harpsichord or lute.[20][note 2] Thus, the first operas had parts sung by soloists and parts spoken or declaimed in monody, known as stile rappresentativo.[12]

These first experiences were a great success, especially among the nobility: the

During the first decades of the 17th century the opera gradually spread: in 1608 was premiered in Mantua

Another introducer of the monodic style in Rome was Paolo Quagliati, who adapted old madrigals of his in opera form: Il carro di fedeltà d'amore (1606), La sfera armoniosa (1623).[28] In the Roman school also stood out Luigi Rossi, who worked for the Barberini. In 1642 he premiered in their theater Il palazzo incantato, a sumptuous production that was a great success. When in 1644 the Barberini had to go into exile in Paris, Rossi accompanied them, and obtained the protection of Cardinal Mazarin, thus helping to introduce opera in France. There he composed his Orfeo (1647), with prologue and three acts, a large production that featured numerous visual effects.[29] Mention should also be made of Domenico Mazzocchi, impresario as well as composer, who initiated the hiring of singers for opera. He was the author of La catena d'Adone (1626).[30] Another exponent was Michelangelo Rossi (Erminia sul Giordano, 1633; Andromeda, 1638).[31]

In Rome it premiered in 1639 Chi soffre, speri, by Virgilio Mazzocchi and Marco Marazzoli, considered the first comic opera.[32]

In these first works one of the first opera singers of recognized talent stood out vocally: Francesco Rasi, a tenor who was already famous before the rise of opera, who participated in the first performances of Peri's Euridice. In 1598 he entered the service of the Gonzaga of Mantua, for which he performed in this city Monteverdi's Orfeo in 1607; the following year he participated in Gagliano's Dafne. He was also a composer, author of Cibele ed Ati (1617), whose music has been lost.[19]

Baroque

The

During this period, the main musical centers were in the monarchic courts, aristocratic circles and episcopal sees. The instrumentation reached heights of great perfection, especially in the violin

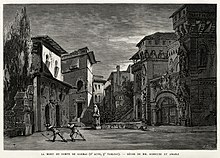

Baroque opera was noted for its complicated and ornate scenography, with sudden changes and complicated lighting and sensory effects. Numerous sets were used, up to fifteen or twenty changes of scenery per performance.

In the first half of the 17th century, the rules of operatic librettos were established, which would undergo few variations until almost the 20th century: simple dialogues and conventional language, stanzas of rigorous forms, distinction between "recitative" —declaimed parts that develop the action — and "number" (or "closed piece") — ornamental parts in the form of aria, duet, choir, or other formats.

Venetian opera

In the middle decades of the 17th century the major opera-producing center was

In Venice the concept of

The Venetian opera was particularly influenced by the Spanish theater of the so-called

Claudio Monteverdi settled in 1613 in Venice, where he was maestro di cappella of the

One of his disciples,

In the vocal field,

French opera

One of the first countries where opera was introduced after Italy was France, where it was called

In 1669, the poet Pierre Perrin and the composer Robert Cambert created a company to perform operas in the French taste and obtained from King Louis XIV the royal privilege to constitute an academy, the Académie Royale de Musique, located in the Jeu de Paume de la Bouteille theater. Both authors produced the opera Pomone, the first written in French, premiered in 1671.[13] However, the following year, Perrin was imprisoned for debt and the royal privilege passed to Jean-Baptiste Lully, a composer of Florentine origin (his real name was Giovanni Battista Lulli).[55] Lully adapted opera to French taste, with choirs, ballets, a richer orchestra, musical interludes and shorter arias.[56] He developed French overture[13] in a slow-fast-slow structure, unlike the Italian, which became almost autonomous pieces of the operatic ensemble.[57] On the other hand, he used to accompany the recitative with a harpsichord continuo bass.[58] At the same time, he gave greater prominence to the text, which provided greater expressiveness to the opera.[59] Likewise, he adapted the singing to the prosody of the French language, creating a typically Gallic vocality called déclamation mélodique.[60] From 1673 until 1687, the date of his death, he composed one opera per year-most with libretti by Philippe Quinault-among them: Cadmus et Hermione (1673), Alceste (1674), Atys (1676), Proserpine (1680), Persée (1682), Phaëton(1683), Amadis (1684), Armide (1686) and Acis et Galatée (1686). The most successful was Alceste, based on a tragedy by Euripides and composed to celebrate the victory of Louis XIV in the Franche-Comté, which included a minor plot with a comic air and some catchy melodies that greatly pleased the public.[61]

Another exponent was

After Lully's operas, and because of the French fondness for ballet, there arose the

Development in Europe

Throughout the seventeenth century opera spread throughout Europe, generally under Italian influence. In Germany -then divided into numerous states of varying political configuration-, the pioneer was

The leading composer of this period was Reinhard Keiser, the first to write operas entirely in German. He composed several operas that enjoyed great success, such as Adonis (1697), Claudius (1703), Octavia (1705) and Croesus (1710). He was director of the Theater am Gänsemarkt, where he premiered on average about five operas per season; his output is estimated to be between seventy-five and one hundred operas, although only nineteen complete ones survive.[67] Other authors of the period were: Johann Wolfgang Franck (Die drey Töchter Cecrops, 1679)[68] and Christoph Graupner (Dido, Königin von Carthage, 1707; Bellerophon, 1708).[69]

In

In England there was a precedent for opera, the

In

In Spain, opera arrived with some delay due to the social crisis caused by the Thirty Years' War. The first opera was premiered in 1627 at the Alcázar de Madrid: La selva sin amor, a pastoral eclogue composed by Bernardo Monanni and Filippo Piccinini on a text by Lope de Vega; the score is not preserved.[13] Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco composed in 1659 La púrpura de la rosa, with text by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, the first opera composed and performed in America, premiered at the Viceroyal Palace of Lima. Juan Hidalgo was the author of Celos aun del aire matan (1660), also with text by Calderón.[67]

In the late 17th century, King

Neapolitan opera

In the second half of the 17th century, the

One of its first composers was Francesco Provenzale, author of Lo schiavo di sua moglie (1672) and Difendere l'offensore overo La Stellidaura vendicante (1674).[82] Also considered a precursor of this type of opera is Alessandro Stradella, despite the fact that he composed most of his operas in Genoa: Trespolo tutore (1677), La forza dell'amor patterno (1678), La gare dell'amor eroico (1679).[83]

Its main representative was

Another outstanding exponent was Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. He died at the age of twenty-six, but had a successful career. In 1732 he composed his first opera, La Salustia, which failed, and Lo frate 'nnamorato, of comic genre, which reaped a notable success. The following year he premiered Il prigionier superbo, in whose intermissions was performed the comic play La serva padrona, which was more successful than the main work. In 1734 he composed Adriano in Siria, with libretto by Pietro Metastasio, in whose intermissions was performed the comic play Livietta e Tracollo, which was more successful than the main work. The following year he premiered L'Olimpiade, still with libretto by Metastasio, and his last work, Il Flaminio, of comic genre, which reaped a notable success.[88]

Nicola Porpora taught singing – he had Farinelli and Caffarelli as pupils – and composition – among his pupils is Johann Adolph Hasse. He was one of the first to musicalize librettos by Pietro Metastasio. Among his early operas are Agrippina (1708), Arianna e Teseo (1714) and Angelica (1720). In 1726 he moved to Venice and, in 1733, to London, where he was musical director of the Opera of the Nobility located at the King's Theatre, where he premiered Arianna in Nasso (1733). He later worked in Dresden, where he premiered Filandro (1747), as well as Vienna, before returning to Naples, where he died in poverty.[88]

Other distinguished representatives were

Late Baroque: opera seria and buffa

The musical production of the first half of the 18th century is usually called late Baroque. The main center of production continued to be Italy, especially Naples and Venice. In 1732 the

Around the second quarter of the 18th century opera was gradually divided into two contrasting genres: the

However, the disappearance of comic characters left a certain void in a sector of the public, generally lower class, who liked these characters. To satisfy them, intermezzi were introduced in the intermissions of the plays, which gradually gained success until they became separate works.

Some of the characteristic elements of the opera buffa were: the use of the recitative accompagnato, greater use of choir and ensembles, and the use of the cavatina and the aria con pertichini, a modality based on an aria -generally da capo – to which were added comments in recitative by characters who watched the scene from outside, generating a form of ensemble. The introduzione and the finale, scenes that usually brought together all the characters of the work, singing in ensemble, also became more relevant.[106]

In the field of opera seria, a unique phenomenon in the history of opera took place in this period: librettists were more relevant than composers, especially two:

Venice remained one of the main operatic centers.

The Neapolitan school also continued, where the split between opera seria and opera buffa took place. Its main representatives in this period were

The Spanish

Mention should also be made of

From the rest of Italy it is worth mentioning Antonio Caldara. He was maestro de cappella in Mantua and Rome before being appointed vice maestro de cappella of Emperor Charles VI in Vienna, where he remained for about twenty years. He collaborated regularly with the librettists Zeno and Metastasio. His work is notable for its use of large chorales. Among his works stand out: Il più bel nome (1708), Andromaca (1724), Demetrio (1731), Adriano in Siria (1732), L'Olimpiade (1733), Demofoonte (1733), Achille in Sciro (1736) and Ciro riconosciuto (1736).[90] Mention should also be made of the Milanese Giovanni Battista Lampugnani (Candace, 1732; Antigono, 1736).[126]

A librettist also stood out in opera buffa:

Among the composers of opera buffa were

Other authors of opera buffa were: Pasquale Anfossi (La finta giardiniera, 1774; La maga Circe, 1788),[130] Gennaro Astarita (Il corsaro algerino, 1765; L'astuta cameriera, 1770),[131] Francesco Coradini (Lo 'ngiegno de le femmine, 1724; L'oracolo di Dejana, 1725),[132] Domenico Fischietti (Il mercato di Malmantile, 1756),[133] Giuseppe Gazzaniga (Don Giovanni Tenorio, 1787),[134] Nicola Logroscino (Il governatore, 1747)[135] and Giacomo Tritto (La fedeltà in amore, 1764).[131]

At this time also appeared the

In the vocal field, at this time it is worth remembering the sopranos

France

At the beginning of this period the Lullian tragédie-lyrique still predominated, where the taste for ballet stood out. Just as Italian opera tended to have three long acts, French opera had five short ones, with ballets interspersed.

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was also an amateur composer, composed an opera, Le devin du village, in 1752. It was of poor quality, but was influential for its introduction of country characters shown as simple and virtuous people, as opposed to the cynical and corrupt nobility, ideals that were echoed in the French Revolution.[108]

In France, opera buffa had its equivalent in the

Other opéra-comique composers were:

Germany and Austria

An indigenous style did not flourish in Germany, and the structure of Italian opera was generally followed.[150] However, the singspiel emerged as a minor genre of comic tone, analogous to the French opéra-comique and the Spanish zarzuela, which alternated dialogue with music and song. The earliest example was Croesus by Reinhard Keiser (1711).[100]

Georg Philipp Telemann performed operas with arias in Italian and recitatives in German. A precocious musician, he composed his first opera at the age of twelve. He was a composer, organist, conductor and creator of the first musical magazine in history, Der getreue Musikmeister. However, his work fell into oblivion and was not recovered until the early 20th century, although his operas today are not performed on the operatic theater circuit.[151] It is estimated that he composed about fifty operas, although only nine are preserved, including Germanicus (1704), Pimpinone (1725) and Don Quichotte auf der Hochzeit des Camacho (Don Quixote at Camacho's Wedding, 1761).[152]

One of the best operatists of the time was

Other exponents were Johann Adolph Hasse, Johann Joseph Fux and Johann Mattheson. Hasse studied in Naples with Scarlatti. His first opera was Antioco (1721), at the age of twenty-two, followed by Sesostrate (1726) and La sorella amante (1729). In 1730 he premiered in Venice Artaserse, which was innovative for its expressive contrasts that allowed a great showcasing of the singers. That year he was appointed director of the Dresden Opera, where he was one of the main promoters of opera seria.[143] He left some seventy operas.[160] Fux was the author of eighteen operas, mostly with librettos by Pietro Pariati, though also by Zeno and Metastasio. His greatest success was Costanza e Fortezza (1723), premiered in Prague at the coronation of Emperor Charles VI as king of Bohemia.[90] Mattheson was a tenor as well as a composer. He worked as an assistant to other operatists, including Keiser, before composing his own. In 1715 he was appointed director of music at Hamburg Cathedral. His works include Cleopatra (1704).[90]

Other countries

In England, too, no national school emerged and the public remained faithful to Italian opera. In 1707, an attempt at English opera, Rosamund, by the musician Thomas Clayton and the writer Joseph Addison, was a resounding failure. In the same year, the opera Semele by John Eccles —with a libretto by William Congreve— was not even premiered. Just as in Germany works with recitative in German and arias in Italian were produced, in England the introduction of the English language did not take off either. Thus, the operatic scene was largely dominated by Handel, along with the premiere of Italian productions.[150] In 1732 the Theatre Royal —also known as Covent Garden— in London, the country's main operatic center, rebuilt in 1809 and 1858; since 1892 it has been called the Royal Opera House.[161]

However, as time went on, audiences began to tire of Händelian operas, which explains the success of

A last attempt at English opera was led by Thomas Arne, composer and producer. He was the author of the comic opera Rosamond (1733) and the serious Comus (1738), as well as the masquerade Alfred (1740), whose song Rule, Britannia! became an English patriotic anthem. He subsequently composed Artaxerxes (1762) —in English— and L'Olimpiade (1765) —in Italian— both with libretto by Pietro Metastasio.[91]

In Denmark, King Federick V protected opera and welcomed the Italian composer Giuseppe Sarti, author of the first opera in Danish: Gam og Signe (1756).[165] Prominent among Danish composers was Friedrich Ludwig Æmilius Kunzen, author of Holger Danske (Holger the Dane, 1789), while the German Johann Abraham Peter Schulz introduced the singspiel genre in Danish (Høstgildet [Harvest Festival], 1790).[166]

In Spain, during the reign of

With the coming to power of the

In

During this period there was also the genre of the tonadilla, some works of lyrical-theatrical character and of satirical and picaresque sign, which were represented in the theatrical intermissions along with sainetes or entremeses. It occurred mainly in the second half of the 18th century. The first work of this genre was Una mesonera y un arriero (1757), by Luis de Misón. Other authors were Antonio Guerrero, Blas de Laserna, Pablo Esteve and Fernando Ferandiere.[170]

In Portugal, opera was supported by King John V, who favored the installation of Italian composers, such as Domenico Scarlatti.[171] Among the Portuguese composers, it is worth mentioning Francisco António de Almeida, author of Italian operas: La pazienzia di Socrate (1733) and La Spinalba, ovvero Il vecchio matto (1739).[172]

Galant music and gluckian reform

In the second third of the 18th century some voices began to emerge critical of opera seria, which was considered stultified and too much geared to vocal flourishes. The first criticisms came from some writings such as Il teatro alla moda by

The main center of galant music was the Germanic area (Germany and Austria), where it is known as Empfindsamer Stil ("sentimental style"). In Germany, it had an early precedent in the late work of Telemann and Mattheson. Its main representative was

In Austria,

In the Germanic sphere was the golden age of

In France, the galant style was already denoted in the work of Rameau and, more fully, in Joseph Bodin de Boismortier (Les Voyages de l'Amour, 1736; Daphnis et Chloé, 1747) and Jean-Joseph de Mondonville (Daphnis et Alcimadure, 1754).[191]

In Italy, gallant music had less incidence, given the presence of the Venetian and Neapolitan schools. Even so, it is denoted in the work of Niccolò Piccinni, Domenico Scarlatti and Baldassare Galuppi, as well as in

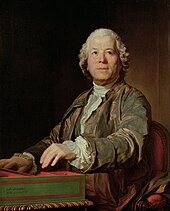

During this period a reform in opera was introduced that pointed to a change of style that would culminate in classicism. Its architect was the German Christoph Willibald Gluck. He studied in Milan, where he premiered in 1741 Artaserse, with a libretto by Metastasio. In 1745 he moved to London, where he unsuccessfully sought Händel's support; he therefore settled in Vienna the following year, until 1770, when he settled in Paris.[194] Among the reforms introduced by Gluck were: preeminence of the plot over vocal improvisations, with more truthful characters; austere music, without ornamentation; limitation of recitatives, all with orchestral accompaniment; overture, choir and ballet are integrated into the action of the opera; abolition of the da capo in the arias; music at the service of the text, harmonizing both elements.[195] On the other hand, as opposed to the concept of closed numbers of Italian opera, Gluck introduced the tableau ("tableau"), a scenic concept that turned each act into a dramatic-musical unit encompassing soloists, choir, ensembles and ballets, which formed an organic ensemble scene. This concept was especially developed in 19th-century French opera.[196]

Among his works are: Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), Alceste (1767) and Paride ed Elena (1770), premiered in Vienna; and Iphigénie en Aulide (1774), Armide (1777), Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) and Écho et Narcisse (1779), premiered in Paris. His regular librettist was Raniero di Calzabigi.[197] During his stay in France, the so-called quarrel of Gluckists and Piccinnists (1775–1779) arose between supporters of Gluck's reform and supporters of Italian opera.[198] Gluck did not limit himself to his Reform-Opern (renewed opera), but made some comic works in the Italian style, such as L'ivrogne corrigé (The Corrected Beodle, 1760) and La rencontre imprévue (The Unforeseen Encounter, 1764).[186]

Classicism

The classical music—not to be confused with the general concept of "classical music" understood as the vocal and instrumental music of cultured tradition produced from the Middle Ages to the present day—[note 5] it meant between the last third of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century the culmination of instrumental forms, consolidated with the definitive structuring of the modern orchestra.[199] Classicism was manifested in the balance and serenity of composition, the search for formal beauty, for perfection, in harmonious and inspiring forms of high values. It sought the creation of a universal musical language, a harmonization between form and musical content. The taste of the public began to be valued, which gave rise to a new way of producing musical works, as well as new forms of patronage.[200]

Opera continued to enjoy great popularity, although it underwent a gradual evolution in accordance with the novelties introduced by classicism. Along with solo voices there were duos, trios, quartets and other ensembles —even a sextet in Le Nozze di Figaro by Mozart-, as well as choirs, although not as grandiose as the baroque ones. The orchestra was enlarged and instrumental music became increasingly prominent in relation to the vocal line.[201] In 1778 the La Scala Theater of Milan was inaugurated, one of the most famous in the world, with an auditorium of 2800 spectators.[202] Similarly, in 1792 the La Fenice Theater in Venice opened, which has also enjoyed great prestige.[203]

The main composers of classicism were

The main exponent of classicism was the Austrian Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. He was a child prodigy, who toured Europe with his father between the ages of six and fourteen, becoming acquainted with the main musical currents of the time: Italian and French opera, Gallant music, Mannheim school.

After the success of Idomeneo he settled in Vienna, where he was commissioned by Emperor Joseph II to write an opera in German, given the pan-Germanist policy of the monarch. In 1782 he premiered at the Burgtheater Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), set in a Turkish harem. This work broke completely with the baroque style, especially by breaking with the succession of arias and the inclusion of real characters, who express their feelings. Depending on the plot he introduced various musical styles, such as folk music to accompany the maid, or passages with Turkish music, characterized by its strident percussion.[212] He employed a denser orchestra, with more wind instruments. He also introduced an aria in two parts, one slower and one faster (cabaletta). At the end he introduced a vaudeville, a scene that brings together all the characters on stage, whose text makes a synthesis of what happened in the play.[213][note 6]

After two unfinished buffa operas in 1783 (

Another outstanding composer of classicism was Ludwig van Beethoven, halfway to Romanticism. In 1803 he attempted an opera, Vestas Feuer, with a libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder, but the project remained unfinished. Two years later he made what would be his only opera, Fidelio (1805), a singspiel of political-moral character, a drama of romantic style, based on Léonore, ou l'amour conjugale by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly. In this work he denoted the influence of Mozart, especially Così fan tutte and Die Zauberflöte.[219] Due to the little experience he had in the field of opera, the music of this work was symphonic, with an instrumentation so dense that it demanded great efforts from the singers.[220] He later made other attempts to compose operas, such as a Macbeth (1808–1811) or a fairy tale entitled Melusine (1823–1824), which he left incomplete.[221]

In the Germanic sphere mention should likewise be made of:

In Italy, the work of

Antonio Salieri was a pupil of Florian Gassmann, who took him to Vienna in 1766, when he was sixteen. At the age of twenty he composed Le donne letterate (1770), which was a great success, so that in 1774 he was appointed court composer to Emperor Joseph II. In 1784 he was appointed director of the Paris Opera, where he succeeded Gluck. Here he composed several operas in the Gluckian style: Les Danaïdes (1784) and Tarare (1787). In 1788 he was appointed chapel master of the Viennese court, in charge of Italian opera. He composed about thirty operas, both serious and buffas, among which stand out: La fiera di Venezia (1772) and Falstaff ossia Le tre burle (1799). He enjoyed great success during his lifetime, but after his death his popularity declined.[224]

Other exponents were Gaetano Andreozzi (Giulio Cesare, 1789; La principessa filosofa, 1794),

At this time emerged in Italy the genre of the farsa, a variant of the opera buffa of smaller format and generally fanciful plot, unrealistic. Cimarosa composed some farces, such as I matrimoni in ballo (1776) and L'impresario in angustie (1786). Some of its main exponents were:

France experienced a period of transition, as the atmosphere generated by the

In Spain, the figure of

In Portugal, he stood out at this time Marcos António de Fonseca Portugal. He began with short operas in Portuguese, such as A castanheira (1787). In 1792 he settled in Naples, where he performed serious and buffa operas: Cinna (1793), La confusione nata della somiglianza (1793), La vedova raggiratrice (1794), Lo spazzacamino principe (1794), Le donne cambiate (1797), Fernando nel Messico (1797).[239]

In Russia, a taste for opera began at this time at the court of the tsars, thanks especially to the support of Empress

In

In Sweden, Queen Louise Ulrica encouraged the construction of the Drottningholm Theater, inaugurated in 1766, and invited composers such as

In Hungary, incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, opera enjoyed little protection, apart from that exercised by the Esterházy, Haydn's protectors. József Chudy was the author of the first opera in Hungarian, the singspiel Pikkó Herceg (Duke Pikkó, 1793, now lost).[248]

In these years opera was being introduced in North America: in United States, the first performances were given at the John Street Theater in New York, opened in 1767. Among the opera's pioneers were Benjamin Carr (The Archers, or the Mountaineers of Switzerland [The Archers, or the Mountaineers of Switzerland], 1796) and John Bray (The Indian Princess, 1808).[249] In Canada, the French Joseph Quesnel was the first author of operas in that country: Colas et Colinette (1805), Lucas et Cécile (1809).[250]

Among the singers, at this time it is worth remembering: Austrian soprano Caterina Cavalieri, Salieri's pupil and lover, for whom Mozart wrote the role of Konstanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail and that of Elvira in Don Giovanni; English soprano Nancy Storace, sister of composer Stephen Storace, for whom Mozart wrote the role of Susanna in Le Nozze di Figaro; Joseph Legros, tenor and composer, who performed roles by Lully, Rameau, Grétry and Gluck; and German tenor Anton Raaff, for whom Mozart wrote his Idomeneo.[251]

19th century

Between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, the foundations of the contemporary society were laid, marked in the political field by the end of absolutism and the establishment of democratic governments. -an impulse initiated with the

In music, the most outstanding aspect was the progressive independence of composers and performers from the patronage of the aristocracy and the Church. The new addressee was the public, preferably the bourgeoisie, but also the common people, in theaters and concert halls. The new situation gave the musician greater creative freedom, but also deprived him of the previous security provided by his patrons, as he was subject to the ups and downs of success or failure.[254]

Opera developed in this century in an increasingly grandiloquent manner, on large stages and with large scenographic stagings, with larger and larger orchestras performing more powerful and sonorous music. This forced vocal performers to increase their singing power, to fill the entire theater and to be heard above the instruments. To this end, new techniques of voice enhancement appeared and new registers emerged, such as the "robust tenor", the "tenore di forza" and the "dramatic soprano".[255]

In the second half of this century, the operetta was established as a minor genre of opera, based on a theatrical piece with dances and songs alternating with dialogues, with light music of popular taste. It became established in France as a derivation of opéra-comique, in small theaters such as the Bouffes-Parisiens sponsored by the composer Jacques Offenbach. It was also well established in Vienna, where it was nourished by the traditional German singspiel.[57] This type of work gave rise to the current musical.[256]

During this century numerous innovations and advances were introduced in the scenographic field, especially in lighting: in 1822 the

Romanticism

Romantic music survived for almost the entire century, until the appearance of the musical avant-garde of the 20th century.

This period saw a remarkable development of opera, especially in Italy, where it was the golden age of

In this period the librettos varied in themes and plots, but had few structural transformations, so that conventional language and the simplification of dialogues and situations predominated as in previous eras.

France

The germ of romantic opera arose in France, where opera seria and opera buffa tended to converge, at the same time that the Gluckian reform was coming to fruition. The recitatives with harpsichord were discarded and became orchestral. The plots based on the Greco-Latin classics were abandoned to set the new romantic dramas to music, with a preference for medieval settings (bards, troubadours) or popular legends. At this time the so-called

The beginnings of French romantic opera are situated in the post-revolutionary environment. The change of regime entailed the replacement of classical mythological themes, linked to the aristocracy, by new themes and characters based on popular heroism, with a series of works that were called "salvation opera", including Les rigueurs du cloître (1790) by

Paradoxically, among the first exponents of French romantic opera were two Italian composers established in France:

Cherubini had several pupils, among whom

Among the earliest exponents of French romanticism was also François-Adrien Boieldieu. He composed his first opera, La fille coupable (1793), at the age of eighteen. Established in Paris, he triumphed with his comic operas, but he also tried other genres, as in Le Calife of Baghdad (1800), of exotic and oriental taste. After a stay in Russia, on his return he renewed his success with Jean de Paris (1812). His greatest success was La dame blanche (1825).[276]

The greatest champion for the beginning of the grand-opéra was the German Giacomo Meyerbeer. He settled in Paris in 1831, when he had his first success with Robert le diable, set in medieval Sicily. His masterpiece was Les Huguenots (1836), about the persecution of French Protestants (Huguenots) in the 16th century, which was notable for its lavish staging. His third major success was Le Prophète (The Prophet, 1849).[277] Robert le diable included a ballet – the Ballet of the Nuns — in which the dancers, in the role of spirits rising from the tombs, were dressed in white tulle, which became the classic ballet costume (the tutu); this work is considered the first modern ballet in history.[278]

In a second generation —sometimes referred to as late Romanticism—

Charles Gounod began in church music, until he turned to opera, with a total of twelve works in his career. His first works were of the grand-opéra genre (Sapho, 1851; La nonne sanglante, 1854), but were not very successful, so he switched to opéra-comique. He chose a play by Molière, Le médecin malgré lui, which he premiered in 1858. It was followed by Faust (1859), his masterpiece. His later works include Mireille (1864) and Roméo et Juliette (1867).[283]

Ambroise Thomas was a classicist, a fervent detractor of Wagner and "modern" music. He composed nine operas, strictly based on the French tradition. His first success was La double échelle (The Double Staircase, 1837). He treated the comic genre with Le songe d'une nuit d'été (The ground of a summer night, 1850), not based on Shakespeare despite the title. He was influenced by Gounod, as seen in Mignon (1866) and Hamlet (1868).[284]

Another German,

Léo Delibes excelled especially in operetta and ballet. His first success, Deux vieilles gardes (1856), already denoted his facility for composing melodies. His masterpiece was Lakmé (1883), set in colonial India, which was notable for its exoticism.[289]

Emmanuel Chabrier studied law, but eventually turned to his greatest hobby, music. A great admirer of Wagner, in 1886 he premiered Gwendoline, where he used the Wagnerian leitmotif.[291] He later turned, however, toward light music of comic tone, with which he achieved his greatest success, Le roi malgré lui (The King in spite of himself, 1887).[292]

Other composers of French Romanticism were:

Italy

In Italy, Romanticism had a markedly populist and nationalist component, in which opera was a means of political vindication for the unification of the peninsula, which would take place in 1870.[301] It was the era of the bel canto, of the showcasing of voices, especially soprano voices. Composers such as Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti were staunch defenders of bel canto, at a time in Europe in general when the orchestra was becoming more and more prominent.[302] However, classical bel canto came to a virtual end with Rossini, while Bellini and Donizetti introduced some innovations, such as the substitution of the canto fiorito for the canto declamato, and the reservation of bel canto passages for moments of intensity, as in the cabaletta or the so-called madness arias, in any case with less vocal ornamentation.[303]

The first great name of the period was

In 1816 he premiered at the

The next figures of Romanticism were

Donizetti achieved his first success with his eighth opera,

At the beginning of Romanticism,

The brothers Luigi and Federico Ricci composed several works both together and separately, and are remembered as the authors of the last traditional opera buffa: Crispino e la comare (1850).[333]

Late Romanticism was dominated in Italy by the figure of

After a first opera that was never performed (Rocester, 1836), with

Next came his three masterpieces:

His next work was

After Verdi, the work of two composers who already foreshadowed a certain change of style that would materialize at the end of the century with verismo was outstanding: Arrigo Boito and Amilcare Ponchielli. Boito was a composer and librettist, author of the librettos of Verdi's last operas. His first opera was Mefistofele (1868), based on Goethe's Faust, which failed, so he temporarily abandoned composition and devoted himself to writing. However, after some revisions and thanks to Verdi's support, in 1875 he revived it, and this time it was a success. Two years later he began Nerone, on which he worked for forty years until his death. Completed by Vincezo Tommasini and Arturo Toscanini, it was premiered in 1924.[352] Ponchielli composed nine operas, although he succeeded with only one, La Gioconda (1876), based on a play by Victor Hugo adapted for libretto by Arrigo Boito. His first work, I promessi sposi (1856), had little success. I Lituani (1874) was well received, but did not remain in the operatic repertoire. He tried orientalism with Il figliuol prodigo (1880) and the comic genre with Marion Delorme (1885).[353]

Other Italian composers of the period were: Luigi Arditi (I briganti, 1840; Gulnara, 1848; La spia, 1856),[354] Giovanni Bottesini (Cristoforo Colombo, 1848; Marion Delorme, 1864),[355] Antonio Cagnoni (Don Bucefalo, 1847; Papà Martin, 1871),[349] Michele Carafa (Jeanne d'Arc, 1821; Le nozze di Lammermoor, 1829),[356] Carlo Coccia (Maria Stuarda, 1833; Caterina di Guisa, 1833),[357] Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869),[358] Francesco Morlacchi (Il barbiere di Siviglia, 1816; Tebaldo ed Isolina, 1820; La gioventù di Enrico V, 1823),[359] Carlo Pedrotti (Fiorina, 1851; Tutti in maschera, 1869),[360] Errico Petrella (Mario Visconti, 1854; Jone, 1858),[361] Lauro Rossi (I falsi monetari, 1846; Il dominò nero, 1849; La sirena, 1855; Lo zingaro rivale, 1867)[362] and Nicola Vaccai (Giulietta e Romeo, 1825).[363]

Germanic countries

In Germany, musical activity was distributed among the various states into which the nation was divided, until the unification of the country in 1871, which brought greater cultural patronage from the reigning house, the

Carl Maria von Weber is considered the creator of German national opera.[365] He was director of the Dresden Opera House,[366] from where he promoted several reforms in opera, such as the arrangement of the orchestra and choir, and a rehearsal schedule that encouraged performers to study the drama rather than the music.[367] He wrote his first opera at the age of twelve, Der Macht der Liebe und des Weins (The Power of Love and Wine, 1798), which was followed by Das Waldmädchen (The Woodland Girl, 1800, which he later remodeled and retitled Silvana, 1810), Peter Schmoll und seine Nachbarn (Peter Schmoll and His Neighbors, 1803) and Abu Hassan (1811).[367] His main opera is Der Freischütz (The Poacher, 1821), a theme based on folk legends: the whole action takes place in a forest, with elements alluding to nature, mystery, magic and populism, all the necessary ingredients for a romantic opera. With this opera, Weber created the German national opera and, at the same time, the first fully Romantic opera.[366] His next opera, Euryanthe (1823), was not so successful. His last opera, Oberon (1826), commissioned in English by the Royal Opera in London, is based on Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Except in Germany, his operas are not widely performed today, but his overtures still enjoy fair fame as symphonic pieces.[368]

Notable in early German Romanticism were the works of

The Austrian

Other famous Romantic composers, such as

The following figures of the period were

In a second generation, the figure of

After a first attempt at an unfinished opera (

His next project was the tetralogy

He combined this project with

Notable among the latter figures was

It is also worth naming among the composers of romantic opera from the Germanic sphere:

In the second half of the century, especially in Austria, there was a revival of operetta, which enjoyed great popularity in Viennese society. Its most prominent representative was

Other countries

In Spain, opera was directly influenced by Italy, to the point that the production of local authors was in Italian. The work of

The English John Fane, founder of the Royal Academy of Music in London, left works in Italian: Fedra (1824), Il torneo (1829), L'assedio di Belgrado (1830).[406]

In Russia, where during the reign of Catherine II the taste for Italian opera had predominated, with Alexander I it was French opera that was in vogue. Even so, the Italian Catterino Cavos, installed in the country, was appointed director of the Imperial Theater of St. Petersburg and premiered several operas, such as Ilya Bogatyr (1807) and Ivan Susanin (1815). Russian composers include: Stepan Davydov (Lesta, 1803), Alekséi Titov (Yam, ili Pochtovaja stancija [Yam, or the Post Office Station], 1805) and Alekséi Verstovski (Askol'dova mogila [Askold's Tomb], 1835).[407]

In Poland,

The Czech

Romantic Singers

Among the lyrical interpreters of Romanticism it is worth remembering:[411][412]

- Isabella Colbran, Spanish mezzo-soprano, Rossini's wife, in many of whose operas she performed, considered one of the first "divas"

- Giovanni Davide, Italian tenor, for whom Rossini wrote some roles

- Gilbert Duprez, French tenor, first figure of the Paris Opera for twelve years

- Cornélie Falcon, French mezzo-soprano of short but brilliant career

- Manuel del Pópulo Vicente García, Spanish tenor and composer, interpreter of Rossini's works, father of María Malibrán, mezzo-soprano

- Julián Gayarre, Spanish tenor with a wide international career

- Giulia Grisi, Italian soprano of international success

- Jenny Lind, Swedish soprano and prima donna, one of the most famous of the century

- Jean-Blaise Martin, French baritone who for his register of one octave more in falsetto gave name to the so-called baritone Martin

- Giuditta Pasta, Italian soprano considered one of the best exponents of bel canto

- Adelina Patti, Italian soprano and diva, considered the best of the last quarter of the 19th century

- Fanny Persiani, Italian soprano ideal in heroine roles

- Jean de Reszke, Polish tenor of attractive physique perfectly suited to romantic roles

- Giovanni Battista Rubini, Italian tenor of sweet, but powerful voice

- Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld, German tenor, the first heldentenor Wagnerian

- Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, German soprano who was noted for her sentimentality

- Henriette Sontag, German soprano of whom Rossini said she had the purest voice[citation needed]

- Teresa Stolz, Czech soprano who excelled especially in Verdi roles

- Francesco Tamagno, Italian tenor famous for his C de pecho

- Enrico Tamberlick, Italian tenor with a powerful voice and vibrant tone

- Giovanni Battista Velluti, the last castrato of renown

Nationalism

In the second half of the 19th century—especially since the liberal revolutions of 1848—numerous nations that had not previously excelled in music experienced a musical renaissance, enhanced by the nationalist sentiments associated with Romanticism and political liberalism. In general, most of these compositions were linked to musical Romanticism, though often with a national component based on the folk and popular tradition of each of these countries.[413] Most plots were historical and national—Rimsky-Korsakov devoted thirteen of his fifteen operas to Russian themes—and vernacular languages were introduced into the operatic texts. Several of these nations did not enjoy political autonomy at the time, so that opera —and culture in general— were identity factors of national vindication. These movements lasted in many cases until the beginning of the 20th century.[414]

Russia

The

The seat of the Imperial Opera was at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in

Aleksandr Dargomizhski, a friend of Glinka's, was similarly committed to creating a national opera grounded in Russian folklore. His first opera, Esmeralda (1840), was based on

The next impulse came from a group of composers known as

Another outstanding exponent was

Other exponents were: Aleksandr Aliabiev (Burya, 1835; Rusalka, 1843),[174] Anton Arensky (Son na Volge, 1891; Raphael, 1894),[433] Mikhail Ippolytov-Ivanov (Ruth, 1887),[434] Anton Rubinstein (The Demon, 1875)[435] and Aleksandr Serov (Judith, 1863; Rogneda, 1865).[436]

In Ukraine, belonging to Russia until 1991, Mykola Lysenko was the leading Ukrainian-language composer: Natalka Poltavka (1889), Taras Bulba (1890). His work was admired by Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, but was not widely disseminated because he refused to have it translated into Russian.[437]

Czechoslovakia

In the 19th century, Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic) and Slovakia were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The liberal revolutions of this period – especially that of 1848 – awakened the yearning for independence in these regions, which was stifled. It was not until the end of World War I that the state of Czechoslovakia, now divided between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, was formed.[438] Czech opera started from the German singspiel, with a popular and folkloric component.[439] Its first exponent was František Škroup, author of the first opera in Czech: Dráteník (The Boilermaker, 1829).[440]

The father of Czech nationalism was

Antonín Dvořák was an outstanding symphonist, author of ten operas that continued the path begun by Smetana. He began with comic works, such as Šelma sedlák (The Sly Peasant, 1877). His masterpiece was Rusalka (1901), with libretto by fellow composer Jaroslav Kvapil, a lyrical love story far removed from the explosive realist dramas that triumphed at the time.[289]

Zdeněk Fibich combined traditional Czech music with the influence of Wagner, Weber and Schumann. He set to music works by Schiller, Byron and Shakespeare, as well as from Greek (Hippodamia, 1889) and Czech mythology (Šárka, 1897).[442]

Other composers were: Karel Bendl (Černohorci [The Montenegrins], 1881; Karel Škréta, 1883),[444] Eduard Nápravník (Nizhegorodski, 1868; Harold, 1886; Dubrovski, 1895; Francesca da Rimini, 1902),[445] Vítězslav Novák (Karlstejn, 1916; Lucerne [The Lantern], 1923)[446] and Otakar Ostrčil (Vlasty Skon [The Death of Vlasta], 1904; Honzovo království [The Kingdom of Johnny], 1934).[447]

Hungary

Wagnerism influenced the work of Ödön Mihalovich, founder of the Budapest Wagner Society and author of Toldi szereime (Toldi's Love, 1893), clearly reminiscent of Wagner.[449]

Later, Béla Bartók combined his own style with traditional Hungarian folk melodies, to which he adapted the asymmetrical patterns of his country's language. He composed a single opera, A kékszakállú herceg vara (The Castle of Barbazul, 1918), based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck, one-act with prologue.[450]

Poland

Poland belonged at this time to Russia. The pioneer of modern Polish opera was Stanisław Moniuszko. He composed several operettas until he moved to the big genre with Halka (1847), his greatest success. In this, as in almost all his works, he showed the relations between the Polish nobility and the townspeople as victims of their cruelty. In his works he introduced Polish folk dances, such as the mazurka or the polonaise.[454] After him, for a time the Wagnerian influence was felt, as in the work of Władysław Żeleński (Konrad Wallenrod, 1885) and Ludomir Różycki (Meduza, 1912).[455]

After Poland's independence, which occurred after World War I, Karol Szymanowski was the main architect of a Polish national music. He lived in Zakopane, in the Tatra Mountains, where he studied the syncopated rhythms played there. His first work was Hagith (1913), which denoted German, French and Russian influences. His masterpiece was Król Roger (King Roger, 1924), an evocative, richly nuanced and colorfully orchestrated work, somewhat influenced by Maurice Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé.[456] Other composers were: Ignacy Jan Paderewski (Manru, 1901),[332] Henryk Opieński (Maria, 1905) and Witold Maliszewski (Syrena, 1927).[455]

In

In Sweden, after the presence of German composers in the beginnings of Swedish opera in the late 18th century, the 19th century saw the emergence of the first national authors, such as

Norway belonged to Denmark until 1814, and to Sweden until 1905. The first Norwegian opera was Fjeldeventyret (An Adventure of the Countryside, 1824), by Waldemar Thrane. For his part, Martin Andreas Udbye was the author of the opera Fredkulla (1858) and some operettas. Other exponents were: Ole Olsen (Stig Hvide, 1876; Lajla, 1893; Stallo, 1902), Catharinus Elling (Kosakkerne [The Cossacks], 1897), Johannes Haarklou (Marisagnet [The Legend of Mary], 1910) and Christian Sinding (Der heilige Berg [The Holy Mountain], 1914).[460]

Belgium and the Netherlands

The Netherlands came into contact with opera thanks to French or Italian traveling companies. The first Dutch opera author was Johannes Bernardus van Bree, author of Sapho (1834) and Le Bandit (1840). In general, opera has been of little interest to Dutch composers. Of note is the opera Halewijn by Willem Pijper (1933).[462]

English-speaking countries

In United Kingdom we cannot speak of an opera of nationalist vindication in the political sense that it had in other countries, but there were attempts to create an English opera alien to Italian, French or German influences. In the field of serious opera this initiative did not take off, despite attempts by authors such as

Two other Irish composers developed their work in London, like Balfe: William Vincent Wallace and Charles Villiers Stanford. The former traveled in several countries until he settled in London, where he achieved an early success with the Italianate opera Maritana (1845). After several works of lesser acclaim he produced The Amber Witch (1861), Love's Triumph (1862) and The Desert Flower (1864).[467] Stanford studied in London and Germany. He was the author of several operas in English: Shamus O'Brien (1896), Much Ado About Nothing (1908), The Traveling Companion (1925).[468] Also worth mentioning among British composers are: Granville Bantock (Caedmar, 1893; The Seal Woman, 1924),[469] John Barnett (The Mountain Sylph, 1834; Fair Rosamond, 1837),[470] Julius Benedict (The Lily of Killarney, 1862),[444] Isidore de Lara (Messaline, 1899; Naïl, 1912)[471] and Ethel Smyth (The Boatswain's Mate, 1916).[472]

In the field of comedic opera, however, there was more fortune, in keeping with the long-standing success of ballad opera, which was renewed by a new type of operetta produced by the tandem Arthur Sullivan (composer)—W. S. Gilbert (playwright), which inaugurated a genre called Savoy opera — after the theater where they were performed.[256] Their collaboration began with Thespis (1871) and they had a first success with Trial by Jury (1875). Their best works were The Mikado (1885) and The Gondoliers (1889), which already reflected their disagreements, until soon after they parted ways. Sullivan tried his hand at serious opera with Ivanhoe (1891), on Walter Scott's play.[473]

In Ireland, during the 19th century, mostly Italian opera triumphed, as well as some in English. Composers such as Michael Balfe, Vincent Wallace and Charles Stanford settled in London and wrote in English. It was not until the 20th century that operas were composed in Irish, the first of which was by Robert O'Dwyer (Eithne, 1910). Later of note was Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer (Sruth na Maoile [Moyle's Sea], 1923).[474]

In the United States the fondness for European opera grew throughout the 19th century. In 1883 the Metropolitan Opera House opened in New York City, the most prestigious theater in the country, which in 1966 moved to a new building at

George Gershwin combined classical music with elements of American popular music, especially jazz and blues. In 1922 he premiered the jazz-opera Blue Monday, which was not very successful. His next project was Porgy and Bess (1935), a folk-opera incorporating jazz and blues rhythms, with a libretto by his brother, Ira Gershwin, and DuBose Heyward. It was not very well received initially, although over time it grew in prestige until it was considered one of the best American operas.[482]

Baltic countries

The current

Latvia was in the Germanic cultural sphere, so this influence predominated in the origin of its operatic tradition. In 1919 the Latvian National Opera (Latvijas Nacionālā Opera) opened in Riga, where the Latvian opera Banjuta by Alfrēds Kalniņš premiered in 1920. His son Jānis Kalniņš was the author of Hamlet (1936). Other exponents of Latvian opera were the brothers Jānis Mediņš (Uguns un nakts [Fire and Night], 1921) and Jāzeps Mediņš (Vaidelote [The Vestal], 1927).[484]

Lithuania, closer to Poland, received like Poland the initial influence of Italian opera. In 1922 the Lithuanian National Theater (Lietuvos Tautas Teatras) was founded in Vilnius. The first Lithuanian opera was Birutė (1906) by Mikas Petrauskas. Subsequent highlights included Antanas Račiūnas' (Trys talismanai [Three Talismans], 1936) and Jurgis Karnavičius (Gražina, 1932).[485]

Balkan countries

Romania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, after which it joined European cultural life. The closeness of Romanian – a language of Latin origin – to Italian favored the spread of Italian opera.[487] Among the pioneers was Ciprian Porumbescu, author of the operetta Crai nou (New Moon, 1880). Later Nicolae Bretan (Luceafărul, 1921) and, mainly, George Enescu, trained in France, where he was a pupil of Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. In 1917 he composed his opera Œdipe (Oedipus), whose manuscript he lost during a trip, so he had to rewrite it and finally premiered it at the Paris Opera in 1936. It was a grandiloquent work, requiring three groups of timpani and machinery to simulate wind.[488]

In Serbia, under Ottoman rule, opera was not introduced until the last quarter of the 19th century. It became independent in 1882, to become part after World War I of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later Yugoslavia. In 1894 the National Theater (Pozorište Narodno) of Belgrade was founded. The pioneer of Serbian opera was Petar Konjović (Koštana, 1931).[497]

Greece became independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1830. Soon several Italian companies were established and a taste for opera began. In 1888 the Greek Opera was founded in Athens, since 1939 Royal Opera and, nowadays, National Opera. An early pioneer in the genre was Spyridon Xyndas, who composed some operas in Italian and one in Greek (O ypopfisios vouleftis [The Parliamentary Candidate], 1867). Subsequent highlights included Manolis Kalomiris (O Protomastoras [The Master Builder], 1916), Dionysios Lavrangas (Ta dyo adelfia, [The Two Brothers], 1900; Dido, 1909) and Theophrastos Sakellaridis (O Vaftistikos [The Godson], 1918).[498]

Turkey and Caucasus countries

In the

In Armenia, whose territory was divided between Turkey and Russia, opera enjoyed great popularity. The first Armenian opera was due to Tigran Chukhachean (Arshak Erkrod, 1868). Subsequently, Armen Tigranian (Anusha, 1912) and Alexander Spendiaryan (Almast, 1928) stood out.[500]

In Georgia, Italian opera was introduced in the mid-19th century. The first Georgian composer of some renown was

In

Portugal

In Portugal, Italian opera predominated during the 19th century, with few local productions. In 1793, the Teatro São Carlos in Lisbon was inaugurated. The first prominent composer was José Augusto Ferreira Veiga (L'elisir di giovinezza, 1876; Dina la derelitta, 1885).[239] In a tardo romanticismo he emphasized Alfredo Keil (Dona Branca, 1883; Irene, 1893; Serrana, 1899).[503]

Spain

In Spain it is not possible to speak of nationalism as such: a Spanish nationality was not claimed against a foreign dominator, no patriotic identities or lost cultural essences were asserted, no formulas from the past were sought, neither popular legends nor traditional folklore were resorted to. On the other hand, the different regional modalities of popular music were used (

The pioneer of opera in Spain was

Other pioneers were Ruperto Chapí and Tomás Bretón. Chapí studied in Paris thanks to a scholarship obtained after composing the short opera Las naves de Cortés (1874). In 1876 he premiered La hija de Jefté at the Teatro Real. From then on he devoted himself mainly to zarzuela, but still composed several operas, such as Roger de Flor (1878), Circe (1902) and Margarita la tornera (1909).[506] Bretón studied in Italy and Vienna. He began with the short opera Guzmán el Bueno (1878), which was followed by Los amantes de Teruel (1889), Garín (1892), La Dolores (1895) and Raquel (1900).[507] In some of his works he introduced Spanish folk music, such as a sardana in Garín and a jota in La Dolores.[508]

Among the great composers of the period are

Other exponents were:

Also worth mentioning are:

In this century the

Towards the end of the century the "género chico" was more fashionable, one-act plays, with more recitative, with a certain influence of Viennese operetta.

After the Spanish Civil War, zarzuela was in decline, until its virtual disappearance in the 1960s. Today, the classics of the genre are still performed, but there is no new production.[525]

Latin America

Latin American opera underwent a gradual evolution over time: during the colonial period, Italian or Spanish operas were performed; after the independence of the colonies, native works began to be produced, but which followed the rules of Italian opera; over time, local elements were added, generally with a folkloric or popular air; finally, works of a universal character began to be produced.[13]

In

In Brazil, when the Portuguese court moved to the new continent in 1808, due to the Napoleonic invasion, it brought with it a taste for Italian opera. Gradually, local composers emerged, among them Carlos Gomes, the first Latin American composer to triumph in Europe (Joana de Flandres, 1863;

In Colombia, the first production was Ester (1874), by José María Ponce de León. In Chile, Telésfora (1841), by Aquinas Ried.[542]

Cuba began in the operatic tradition while a Spanish colony. Throughout the 19th century, Italian opera triumphed above all. In 1875, Laureano Fuentes Matons composed the first Cuban opera, La hija de Jefté. Later, Ignacio Cervantes (Los Saltimbanquis, 1899) and Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes (El náufrago, 1901). There were also composers of zarzuelas, such as Ernesto Lecuona (María la O, 1930; El cafetal, 1930) and Eliseo Grenet (Niña Rita, 1927; La virgen morena, 1928).[543]

In Guatemala, Italian opera was introduced in the early 19th century. In 1859 the Teatro Carrera, later called Nacional and, since 1886, Colón, was inaugurated. The first local opera was La mora generosa (1850), by José Escolástico Andrino. Already in the 20th century, Jesús Castillo (Quiché Vinak, 1924) stood out.[544]

Mexico had an operatic tradition from its colonial past: a Mexican opera, La Parténope (1711), by

In Nicaragua, Luis Abraham Delgadillo was outstanding: Final de Norma (1930), Mabaltayán (1942).[542]

In Peru, European cultural life was closely followed in the 19th century. The first opera in the country was Atahualpa (1875), by the Italian Carlo Enrico Pasta. Subsequently, José María Valle Riestra (Ollanta, 1900) and Ernesto López Mindreau (Nueva Castilla, 1926) stood out.[547]

In

In Venezuela, it is worth mentioning: José Ángel Montero (Virginia, 1873) and Reynaldo Hahn (Le Marchand de Venise, 1935).[542]

Verismo

Italian

The beginning of the success of verismo was with two operas: Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni and Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo. Mascagni worked as a conductor with various companies throughout Italy until 1888, when he entered a musical competition organized by the publisher Edoardo Sanzogno with the one-act opera Cavalleria rusticana (premiered in 1890), with which he won the competition and reaped an enormous success. Based on a play by Giovanni Verga, it was notable for its ordinary characters driven by violent passions. He did not repeat such success with his following plays: L'amico Fritz (1891), I Rantzau (1893) and Guglielmo Ratcliff (1895).[552] Leoncavallo composed his first opera at the age of nineteen (Chatterton, 1876). Following a commission from the publisher Giulio Ricordi, he undertook a trilogy in the Wagnerian style, which he never completed. After a time in which he devoted himself mainly to writing, the success of Cavalleria rusticana encouraged him again and he composed his greatest success, Pagliacci (1892), a tragic story about four itinerant actors, with libretto written by himself. His next works were not so successful: I Medici (1893), La bohème (1897) and Zazà (1900).[553]

The most outstanding composer of this trend was Giacomo Puccini. A pupil of Ponchielli, he had a great instinct for suggestive melodies and passionate plots, as well as for combining music and drama in perfect harmony, always with the voice as the central axis of his composition. An admirer of Wagner, he used the leitmotiv in several of his works.[554] He had a first success with Le Villi (The Willis, 1884), but for various reasons his next operatic work, Edgar (1889), which was not well received, was delayed. He did achieve great success with Manon Lescaut (1893), which brought him fame and fortune. In collaboration with librettists Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica he created his three most relevant operas: La Bohème (1896), Tosca (1900) and Madama Butterfly (1904). The former, about Parisian bohemian life, blended tragedy, passion and humor, along with seductive music that greatly pleased audiences. Tosca presented an equally tragic plot enhanced by musical dissonances and twisted harmonies, with one of the most complex female roles ever sketched. Her aria E lucevan le stelle is one of the opera's most famous, also known as the Farewell to Life. Madama Butterfly is set in Japan, in keeping with the exotic taste of the time. Although it was not well received at its premiere, over time its tonal coloring and harmonic language have been appreciated. It includes the famous aria Un bel dì, vedremo.[555]

In 1910 he premiered in New York

Other prominent composers of verismo were Umberto Giordano, Alfredo Catalani and Francesco Cilea. Giordano began in Sanzogno's competition with the one-act opera Marina (1889). It was followed by Mala vita (1892) and Regina Diaz (1894). He achieved his greatest success with Andrea Chénier (1896), with libretto by Luigi Illica. He repeated success with Fedora (1898), which was followed by a series of failures, until he renewed fame with La cena delle beffe (The Supper of Mockery, 1924).[442] Catalani evolved from an early Wagnerian influence towards verismo. His first opera, La falce (1875), was to a libretto by Arrigo Boito. It was followed by Elda (1880), transformed ten years later into Loreley. His greatest success was La Wally (1892), in a Germanizing style, with libretto by Luigi Illica.[557] Cilea abandoned law for music. He achieved an early success with Gina (1889), which was followed by La tilda (1892), L'arlesiana (1897) and his masterpiece, Adriana Lecouvreur (1902), a mixture of tragedy and comedy,[558] in which he combined verismo with a certain bel canto.[559]

Otros exponentes fueron: Franco Alfano (Resurrection, 1904),[560] Alberto Franchetti (Christopher Columbus, 1892; Germany, 1902),[561] Franco Leoni (The Oracle, 1905; Francesca da Rimini, 1914),[562] Giacomo Orefice (Chopin, 1901; The Moses, 1905)[563] and Antonio Smareglia (Istrian Wedding, 1895; The Moth, 1897).[564]

Close to verismo, but with a more personal style is

In the 1910s this style evolved towards a so-called post-Verismo, characterized by the strong influence of the writer

Outside Italy, the veristic influence is denoted in the work of the French Gustave Charpentier. He was a pupil of Massenet and, in 1887, won the Rome prize. It was in that city that he was infected by the verist atmosphere and composed his most famous opera, Louise (1900), the love story of two young people from Montmartre, with libretto by Saint-Pol-Roux.[570] Also in France, Alfred Bruneau set to music several texts by Émile Zola, such as Le rêve (1891), L'Attaque du moulin (1893), Messidor (1897), L'Ouragan (1901) and L'Enfant roi (1905).[571] Henry Février was the author of Monna Vanna (1909), on a text by Maurice Maeterlinck, a semi-Viverist work of symbolist inspiration.[572]

In Germany,

The Czech Josef Bohuslav Foerster started in a veristic style with his first two operas Debora (1893) and Eva (1899). Later he was the author of Jessika (1905), based on Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, as well as Nepřemožení (The Invincibles, 1919), Srdce (The Heart, 1923) and Bloud (The Klutz, 1936).[574]

The Greek Spyridon Samaras was the author of operas in Italian in the veristic style: La martire (1894), La furia domata (1895), Rhea (1908).[575]

Post-romanticism

Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there was the post-Romanticism, which as its name suggests was an evolution of Romanticism based on more modern premises, but maintaining the same spirit that characterized that movement. The main influence of this style was Wagner, so it is sometimes also called post-Wagnerism.

Its main representative was

Other exponents were

The Austrian Erich Wolfgang Korngold was considered a child prodigy, and aroused the admiration of Mahler, Puccini and Strauss. His first operas were Der Ring des Polykrates (The Ring of Polycrates, 1916), Violanta (1916) and Die Tote Stadt (The Dead City, 1920), of late romanticism. Das Wunder der Heliane (The Miracle of Heliane, 1927) was a work of a certain eroticism with a score conceived on an epic scale that creates great difficulty for the performers. With the establishment of the Anschluss in 1938, he emigrated to the United States, where he composed film scores and won two Oscars.[580]

In the Germanic field it is also worth mentioning: Wilhelm Kienzl (Der Evangelimann [The Evangelist], 1895),[581] Max von Schillings (Moloch, 1900; Mona Lisa, 1915),[582] Siegfried Wagner —son of Richard Wagner— (Der Bärenhäuter [The Bearskin], 1899; Der Kobold [The Goblin], 1904; Der Schmied von Marienburg [The Blacksmith of Marienburg], 1923)[583] and Hugo Wolf (Der Corregidor, 1895).[584]

The British Rutland Boughton attempted to establish an "English-style Wagnerism", with operas such as The Immortal Hour (1922), Alkestis (1922), The Queen of Cornwall (1924) and The Lily Maid (1934).[355] Similarly, Joseph Holbrooke sought to transfer to Celtic mythology the Wagnerian universe, through the trilogy The Cauldron of Annwyn (1912–1929), consisting of The Children of Don (1912), Dylan, Son of the Wave (1914) and Bronwen (1929).[585]

In France, Gabriel Fauré showed a clear Wagnerian influence in his opera Pénélope (1913).[586] Jean Nouguès was the author of Quo Vadis? (1909), on Henryk Sienkiewicz's novel, a work of an ambitious staging that included circus animals.[587]

In Italy, Luigi Mancinelli showed a clearly Wagnerian style, although with a more cosmopolitan component, not as Germanized as that of other followers of the German composer. His two best works were Ero e Leandro (1897) and Paolo e Francesca (1907).[588]

Impressionism

Like his

Claude Debussy began several operatic projects that he left unfinished-a couple on stories by

In France, Maurice Ravel and Paul Dukas also stood out. Ravel was a convinced anti-Wagnerian, who eagerly searched for his own style. He was very meticulous and nonconformist in his work, so he continually revised his works, which explains his scarce production. With a Basque mother, he felt great attraction for Spanish culture, which is evident in his first opera, L'heure espagnole (La hora española, 1911), a one-act comic work, with sound effects of machines and clocks. His next opera was L'enfant et les sortilèges (1925), with a libretto by Colette.[593] Dukas initially accused Wagnerian influence, as denoted in Horn et Riemenhild (1892) and L'arbre de science (1899), which he left unfinished. He completed only one opera, Ariane et Barbe-bleu (1907), based on the text by Maurice Maeterlinck, where he mixed Wagnerian chromaticism with the pentatonic scale used by Debussy.[488]

The Italian Ottorino Respighi attempted to combine impressionism with traditional music, especially Baroque.[594] His first two operas were of comic genre: Re Enzo (1905) and Semirâma (1910). He subsequently produced Belfagor (1923), La campana sommersa (1927), La Fiamma (1934) and Lucrezia (1937).[595]

British Frederick Delius approached impressionism departing from Wagnerian influence. He only turned to opera early in his career: Koanga (1904), A Village Romeo and Juliet (1907), Fennimore and Gerda (1919).[596]

The Swiss Ernest Bloch brought together the influence of Debussy with that of Richard Strauss. He produced a single opera, Macbeth (1910). In 1916 he emigrated to the United States, where he began an opera that he left unfinished, Jezebel[464]

Singers of the end of the century

At the turn of the century they stood out vocally:

20th century

The 20th century saw a great revolution in music, motivated by the profound political and social changes that took place during the century. The transforming, experimental and renovating interest of the artistic avant-gardes was translated into a new musical language, at the same time that a technical renovation took place, motivated by the appearance of new technologies, such as electronic music. All this resulted in new compositional methods and new sound ranges, which were adapted to the new musical movements that were happening in the course of the century.[598] The new music composed in this century broke radically with the past and sought a new language, breaking the scheme of traditional musical discourse: if necessary, harmony, melody and tonality were broken. Many of these innovations caused bewilderment, especially atonality, in a public accustomed to a hierarchy of notes where a fundamental note dominated; in atonality, each note has equal relevance to the others. For this reason, contemporary music has not enjoyed great public success and has often been confined to a closed circle of intellectuals.[599]

Opera in the twentieth century maintained the previous repertoire, which continued to be successfully performed in the best theaters and auditoriums of the world, while, at the production level, although there was a copious and excellent production, the innovations produced in this field did not enjoy great success among the majority public. The composers' eagerness to experiment provoked harsh criticism and controversy, if not even censorship or political persecution: in the

This century saw numerous novelties in the field of scenography: from verismo emerged a more sober and realistic trend in stage representation, whose pioneers were

At the beginning of this century emerged the

Another phenomenon of relevance in this century was the proliferation of opera festivals, which counted on the example of the

In an article published by Opera Holland Park, the opera director Ella Marchment explained that for every hour of a performance, an opera director will complete 150 hours of preparation and rehearsals; or 2.5 hours of work for every minute of onstage time.[611]

Expressionism

The expressionism emerged at the beginning of the century as a style fundamentally concerned with the inner expressiveness of the individual, in its psychological deepening, as opposed to the dominant naturalism at the turn of the century, which in opera gave the verismo. In this current, interpersonal relationships, emotionality and the psychic states of the characters were especially valued. On a literary level, its referents were Franz Kafka, James Joyce and the German playwrights Ernst Toller, Frank Wedekind and Georg Kaiser. For expressionist authors, art was a form of expression, not entertainment, so they were more concerned with the message they wanted to convey than with style or musical or plot device.[606]

In France, this style was practiced by some composers who formed a group called

In Germany, Franz Schreker began in post-romanticism, but later opted for a style close to expressionism. His first opera was Der ferne Klang (The Far Sound, 1910), with which he achieved great success. It was followed by Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones, 1918), an opera of great complexity that required an orchestra of 120 musicians, with a somber and tortured theme, fully immersed in the depressing spirit of the postwar period. In Der Schatzgräber (The Treasure Hunter, 1920) he also showed a theme centered on loneliness, despair and sexual desire. His last works, Christophorus (1931) and Der Schmied von Gent (The Blacksmith of Ghent, 1932), were sabotaged by the Nazis, who considered him a degenerate musician, with the accentuated motif of being Jewish.[618]

Paul Hindemith started in expressionism with three one-act operas (Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen [Murder, Hope of Women], 1919; Das Nusch-Nuschi, 1920; Sancta Sussana, 1921), but later evolved into a neo-baroque style with use of polyphony. In that sense, Cardillac (1926) was a transitional work, while in Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter, 1928) he combined medieval influences with German folklore and counterpoint techniques. After being considered a degenerate musician by the Nazis, he went into exile in Switzerland and the United States. Die Harmonie der Welt (The Harmony of the World, 1957) was the culmination of his neo-baroque style.[601]

Dodecaphony

The spirit of renewal at the turn of the century, which led all the arts to a break with the past and to seek a new creative impulse, led the Austrian composer

In 1927,

Another field of experimentation was microtonalism, in which

Neoclassicism

The neoclassicism was a return to the musical models of eighteenth-century classicism, characterized by restraint, balance and formal clarity. It developed especially in the interwar period (1920s and 1930s). Its models were basically the classicists, but also recovered baroque forms, as well as various expressive options such as dissonance.[631] In general, more objective and defined musical forms were sought, with a more contrasted and diaphanous timbre, repetitive rhythms – with frequent use of ostinato — and a more diatonic harmony, far from Wagnerian chromaticism.[632]

One of the countries where this style was most prevalent was the