Kerala

This article may be readable prose size was 18,000 words. . (June 2023) |

Kerala | ||

|---|---|---|

| State of Kerala | ||

|

Formation 1 November 1956 | | |

State Legislature | Unicameral | |

| • Assembly | Kerala Legislative Assembly (140 seats) | |

| National Parliament | Parliament of India | |

| • Rajya Sabha | 9 seats | |

| • Lok Sabha | 20 seats | |

| High Court | Kerala High Court | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 38,863 km2 (15,005 sq mi) | |

| • Rank | Official script Malayalam script | |

| GDP | ||

| • Total (2022–2023) | ||

| • Rank | 11th | |

| • Per capita | ||

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) | |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL | |

| Vehicle registration | KL | |

| HDI (2019) | ||

| Literacy (2018) | ||

| Sex ratio (2011) | 1084♀/1000 ♂[11] (17th) | |

| Website | kerala | |

| Symbols of Kerala | ||

| ||

| Bird | Great hornbill[12] | |

| Butterfly | Papilio buddha[13] | |

| Fish | Green chromide | |

| Flower | Golden shower tree[12] | |

| Fruit | Jackfruit[14] | |

| Mammal | Indian elephant[12] | |

| Tree | Coconut Tree[12] | |

| State highway mark | ||

| ||

| State highway of Kerala SH KL1 – SH KL79 | ||

| List of Indian state symbols | ||

| Person | Malayāḷi, Kēraḷīyaṉ |

|---|---|

| People | Malayāḷikaḷ, Kēraḷīyaṟ |

| Language | Malayāḷam |

Kerala (English:

The

Kerala has the lowest positive population growth rate in India, 3.44%; the highest

The

Etymology

The word Kerala is first recorded as Keralaputo ('son of

One folk etymology derives Kerala from the Malayalam word kera 'coconut tree' and alam 'land'; thus, 'land of coconuts',[32] which is a nickname for the state used by locals due to the abundance of coconut trees.[33]

The earliest Sanskrit text to mention Kerala as Cherapadha is the late Vedic text

Malabar

Kerala was alternatively called

History

Traditional sources

According to the Sangam classic

Another much earlier

Ophir

- 1 Kings22:48

- ^ Book of Job 22:24; 28:16; Psalms 45:9; Isaiah 13:12

Cheraman Perumals

The legend of Cheraman Perumals is the medieval tradition associated with the Cheraman Perumals (literally the

According to the

However, S. N. Sadasivan contends in A Social History of India that Kalimanja, the king of the Maldives, was the one who converted to Islam. The story of Tajuddeen in the Cochin Gazetteer may have originated because Mali, as it was known to sailors at the time, was mistaken for Malabar (Kerala).[78]

Pre-history

A substantial portion of Kerala including the western coastal lowlands and the plains of the midland may have been under the sea in ancient times. Marine fossils have been found in an area near

Ancient period

Kerala has been a major spice exporter since 3000 BCE, according to

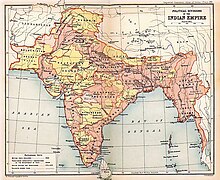

The Land of Keralaputra was one of the four independent kingdoms in southern India during Ashoka's time, the others being

According to the

Merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal posts and settlements in Kerala.

Early medieval period

A

The inhibitions, caused by a series of Chera-Chola wars in the 11th century, resulted in the decline of foreign trade in Kerala ports. In addition, Portuguese invasions in the 15th century caused two major religions,

The rise of Kozhikode

After his death, in the absence of a strong central power, the state was divided into thirty small warring principalities; the most powerful of them were the kingdom of

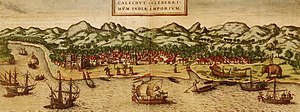

At the peak of their reign, the Zamorins of Kozhikode ruled over a region from Kollam (

Vijayanagara Conquests

The king Deva Raya II (1424–1446) of the Vijayanagara Empire conquered the entirety of present-day state of Kerala in the 15th century.[141] He defeated the Zamorin of Kozhikode, as well as the ruler of Kollam around 1443.[141] Fernão Nunes says that the Zamorin had to pay tribute to the king of Vijayanagara Empire.[141] Later Kozhikode and Venad seem to have rebelled against their Vijayanagara overlords, but Deva Raya II quelled the rebellion.[141] As the Vijayanagara power diminished over the next fifty years, the Zamorin of Kozhikode again rose to prominence in Kerala.[141] He built a fort at Ponnani in 1498.[141]

Early modern period

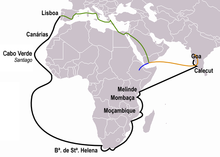

The maritime

The ruler of the

The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between the Zamorin and the King of Kochi allied with Kochi. When

In 1571, the Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the

In 1602, the Zamorin sent messages to Aceh promising the Dutch a fort at Kozhikode if they would come and trade there. Two factors, Hans de Wolff and Lafer, were sent on an Asian ship from Aceh, but the two were captured by the chief of Tanur, and handed over to the Portuguese.[163] A Dutch fleet under Admiral Steven van der Hagen arrived at Kozhikode in November 1604. It marked the beginning of the Dutch presence in Kerala and they concluded a treaty with Kozhikode on 11 November 1604, which was also the first treaty that the Dutch East India Company made with an Indian ruler.[16] By this time the kingdom and the port of Kozhikode was much reduced in importance.[163] The treaty provided for a mutual alliance between the two to expel the Portuguese from Malabar. In return the Dutch East India Company was given facilities for trade at Kozhikode and Ponnani, including spacious storehouses.[163]

The Portuguese were ousted by the

The Kingdoms of Travancore and Cochin, and British influences

The

The island of Dharmadom near Kannur, along with Thalassery, was ceded to the East India Company in 1734, which were claimed by all of the Kolattu Rajas, Kottayam Rajas, and Arakkal Bibi in the late medieval period, where the British initiated a factory and English settlement following the cession.[175][43] In 1761, the British captured Mahé, and the settlement was handed over to the ruler of Kadathanadu.[176] The British restored Mahé to the French as a part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[176] In 1779, the Anglo-French war broke out, resulting in the French loss of Mahé.[176] In 1783, the British agreed to restore to the French their settlements in India, and Mahé was handed over to the French in 1785.[176]

In 1757, to resist the invasion of the

By the end of the 18th century, the whole of Kerala fell under the control of the British, either administered directly or under

There were major revolts in Kerala during the independence movement in the 20th century; most notable among them is the 1921

As a state of the Republic of India

After India was

Geography

The state is wedged between the

Kerala's western coastal belt is relatively flat compared to the eastern region,

Climate

With around 120–140 rainy days per year,

| Climate data for Kerala | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30 (86) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 8.7 (0.34) |

14.7 (0.58) |

30.4 (1.20) |

109.5 (4.31) |

239.8 (9.44) |

649.8 (25.58) |

726.1 (28.59) |

419.5 (16.52) |

244.2 (9.61) |

292.3 (11.51) |

150.9 (5.94) |

37.5 (1.48) |

2,923.4 (115.1) |

| Source: [238][240] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Most of the

Kerala's fauna are notable for their diversity and high rates of endemism: it includes 118 species of

Divisions, districts and cities

| State administrative divisions | |

|---|---|

| Administrative structure | Numbers |

| Districts | 14 |

| Revenue Divisions | 27 |

| Taluks | 75 |

| Revenue Villages | 1453 |

| Local-Self Governments[253] | Numbers |

District Panchayats

|

14 |

| Block Panchayats | 152 |

| Grama Panchayats | 941 |

| Municipal Corporations | 6 |

| Municipalities | 87 |

The state's

In 1664, the municipality of

Government and administration

The state is governed by a parliamentary system of representative democracy. Kerala has a unicameral legislature. The Kerala Legislative Assembly also known as Niyamasabha, consists of 140 members who are elected for five-year terms.[265] The state elects 20 members to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament, and 9 members to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house.[266]

The

Each district has a district administrator appointed by government called

In Kerala, local government bodies such as Panchayats, Municipalities, and Corporations have existed since 1959. However, a significant decentralization initiative began in 1993, aligning with constitutional amendments by the central government.[274] The Kerala Panchayati Raj Act and Kerala Municipality Act were enacted in 1994, establishing a 3-tier system for local governance.[275] This system includes Gram Panchayat, Block Panchayat, and District Panchayat.[276] The Acts define clear powers for these institutions.[274] For urban areas, the Kerala Municipality Act follows a single-tier system, equivalent to Gram Panchayat.These bodies receive substantial administrative, legal, and financial powers to ensure effective decentralization.[277] Currently, the state government allocates around 40% of the state plan outlay to local governments.[278] Kerala was declared the first digital state of India in 2016 and, according to the India Corruption Survey 2019 by Transparency International, is considered the least corrupt state in India.[279][280] The Public Affairs Index-2020 designated Kerala as the best-governed state in India.[281]

Kerala hosts two major political alliances: the

Economy

After independence, the state was managed as a

The state's service sector which accounts for around 63% of its revenue is mainly based upon hospitality industry, tourism, Ayurveda and medical services, pilgrimage, information technology, transportation, financial sector, and education.[292] Major initiatives under the industrial sector include Cochin Shipyard, shipbuilding, oil refinery, software industry, coastal mineral industries,[217] food processing, marine products processing, and Rubber based products. The primary sector of the state is mainly based upon cash crops.[293] Kerala produces a significant amount of national output of the cash crops such as coconut, tea, coffee, pepper, natural rubber, cardamom, and cashew in India.[293] The cultivation of food crops began to reduce since the 1950s.[293] The migrant labourers in Kerala are a significant workforce in its industrial and agricultural sectors. Being home to only 1.18% of the total land area of India and 2.75% of its population, Kerala contributes more than 4% to the gross domestic product of India.

Kerala's economy depends significantly on emigrants working in foreign countries, mainly in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and the remittances annually contribute more than a fifth of GSDP.[294] The state witnessed significant emigration during the Gulf Boom of the 1970s and early 1980s. In 2008, the Persian Gulf countries together had a Keralite population of more than 2.5 million, who sent home annually a sum of US$6.81 billion, which is the highest among Indian states and more than 15.1% of remittances to India in 2008.[295] In 2012, Kerala still received the highest remittances of all states: US$11.3 billion, which was nearly 16% of the US$71 billion remittances to the country.[296] In 2015, NRI deposits in Kerala have soared to over ₹1 lakh crore (US$13 billion), amounting to one-sixth of all the money deposited in NRI accounts, which comes to about ₹7 lakh crore (US$88 billion).[297] Malappuram district has the highest proportion of emigrant households in state.[26] A study commissioned by the Kerala State Planning Board, suggested that the state look for other reliable sources of income, instead of relying on remittances to finance its expenditure.[298]

A decline of about 300,000 in the number of emigrants from the state was recorded during the period between 2013 and 2018.

As of March 2002, Kerala's banking sector comprised 3341 local branches: each branch served 10,000 people, lower than the national average of 16,000; the state has the third-highest bank penetration among Indian states.

The state's budget of 2020–2021 was ₹1.15 lakh crore (US$14 billion).[312] The state government's tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) amounted to ₹674 billion (US$8.4 billion) in 2020–21; up from ₹557 billion (US$7.0 billion) in 2019–20. Its non-tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) of the Government of Kerala reached ₹146 billion (US$1.8 billion) in 2020–2021.[312] However, Kerala's high ratio of taxation to GSDP has not alleviated chronic budget deficits and unsustainable levels of government debt, which have impacted social services.[313] A record total of 223 hartals were observed in 2006, resulting in a revenue loss of over ₹20 billion (US$250 million).[314] Kerala's 10% rise in GDP is 3% more than the national GDP. In 2013, capital expenditure rose 30% compared to the national average of 5%, owners of two-wheelers rose by 35% compared to the national rate of 15%, and the teacher-pupil ratio rose 50% from 2:100 to 4:100.[315]

The Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board is a government owned financial institution in the state to mobilise funds for infrastructure development from outside the state revenue, aiming at overall infrastructure development of the state.[316][317] In November 2015, the

Despite of many achievements, Kerala facing many challenges like high levels of unemployment that disproportionately impact educated women, a high degree of global exposure and a very fragile environment.[322]

Industries

Traditional industries manufacturing items;

Agriculture

The major change in agriculture in Kerala occurred in the 1970s when production of rice fell due to increased availability of rice all over India and decreased availability of labour.[328] Consequently, investment in rice production decreased and a major portion of the land shifted to the cultivation of perennial tree crops and seasonal crops.[329][330] Profitability of crops fell due to a shortage of farm labour, the high price of land, and the uneconomic size of operational holdings.[331] Only 27.3% of the families in Kerala depend upon agriculture for their livelihood, which is also the least curresponding rate in India.[332]

Kerala produces 97% of the national output of black pepper[333] and accounts for 85% of the natural rubber in the country.[334][335] Coconut, tea, coffee, cashew, and spices—including cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg are the main agricultural products.[88]: 74 [336][337][338][339][340] Around 80% of India's export quality cashew kernels are prepared in Kollam.[341] The key cash crop is Coconut and Kerala ranks first in the area of coconut cultivation in India.[342] In 1960–61, about 70% of the Coconuts produced in India were from Kerala, which have reduced to 42% in 2011–12.[342] Around 90% of the total Cardamom produced in India is from Kerala.[26] India is the second-largest producer of Cardamom in world.[26] About 20% of the total Coffee produced in India are from Kerala.[293] The key agricultural staple is rice, with varieties grown in extensive paddy fields.[343] Home gardens made up a significant portion of the agricultural sector.[344] Related animal husbandry is touted by proponents as a means of alleviating rural poverty and unemployment among women, the marginalised, and the landless.[345][346] The state government promotes these activities via educational campaigns and the development of new cattle breeds such as the Sunandini.[347][348] Though the contribution of the agricultural sector to the state economy was on the decline in 2012–13, through the strength of the allied livestock sector, it has picked up from 7.0% (2011–12) to 7.2%. In the 2013–14 fiscal period, the contribution has been estimated at a high of 7.8%. The total growth of the farm sector has recorded a 4.4% increase in 2012–13, over a 1.3% growth in the previous fiscal year. The agricultural sector has a share of 9.3% in the sectoral distribution of Gross State Domestic Product at Constant Price, while the secondary and tertiary sectors have contributed 23.9% and 66.7%, respectively.[349]

There is a preference for organic products and home farming compared to

Fisheries

With 590 kilometres (370 miles) of coastal belt,[353] 400,000 hectares of inland water resources[354] and approximately 220,000 active fishermen,[355] Kerala is one of the leading producers of fish in India.[356] According to 2003–04 reports, about 11 lakh(1.1 million) people earn their livelihood from fishing and allied activities such as drying, processing, packaging, exporting and transporting fisheries. The annual yield of the sector was estimated as 6,08,000 tons in 2003–04.[357] This contributes to about 3% of the total economy of the state. In 2006, around 22% of the total Indian marine fishery yield was from Kerala.[358] During the southwest monsoon, a suspended mud bank develops along the shore, which in turn leads to calm ocean water, peaking the output of the fishing industry. This phenomenon is locally called chakara.[359][360] The waters provide a large variety of fish: pelagic species; 59%, demersal species; 23%, crustaceans, molluscs and others for 18%.[358] Around 1050,000(1.050 million) fishermen haul an annual catch of 668,000 tonnes as of a 1999–2000 estimate; 222 fishing villages are strung along the 590-kilometre (370-mile) coast. Another 113 fishing villages dot the hinterland.

Transportation

Roads

Kerala has 331,904 kilometres (206,236 mi) of roads, which accounts for 5.6% of India's total.

The

Kerala State Road Transport Corporation

Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) is a state-owned road transport corporation. It is one of the country's oldest state-run public bus transport services. Its origins can be traced back to Travancore State Road Transport Department, when the Travancore government headed by Sri. Chithra Thirunnal decided to set up a public road transportation system in 1937.

The corporation is divided into three zones (North, Central and South), with the headquarters in Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala's capital city). Daily scheduled service has increased from 1,200,000 kilometres (750,000 mi) to 1,422,546 kilometres (883,929 mi),[375] using 6,241 buses on 6,389 routes. At present the corporation has 5373 buses running on 4795 schedules.[376][377]

The Kerala Urban Road Transport Corporation (KURTC) was formed under KSRTC in 2015 to manage affairs related to urban transportation.[363] It was inaugurated on 12 April 2015 at Thevara.[378]

Railways

- Thiruvananthapuram Central(TVC)

- Ernakulam Junction (South) (ERS)

- Kozhikode (CLT)

- Kollam Junction (QLN)

- Thrissur (TCR)

- Palakkad Junction(PGT)

- Kannur (CAN)

- Shoranur Junction(SRR)

- Ernakulam Town(North) (ERN)

- Kottayam (KTYM)

- Chengannur (CNGR)

- Alappuzha (ALLP)

- Kochuveli(KCVL)

- Kayamkulam Junction (KYJ)

- Tirur (TIR)

- Kasaragod (KGQ)

- Aluva (AWY)

- Thalassery (TLY)

The first railway line in the state was laid from

Kochi Metro

Airports

Kerala has four international airports:

- Thiruvananthapuram International Airport

- Cochin International Airport

- Calicut International Airport

- Kannur International Airport

Water transport

Kerala has

The 616 kilometres (383 mi) long West-Coast Canal is the longest waterway in state connecting

Kochi water metro

Kochi Water Metro (KWM) is an integrated ferry transport system serving the Greater Kochi region in Kerala, India. It is the first water metro system in India and the first integrated water transport system of this size in Asia, which connects Kochi's 10 island communities with the mainland through a fleet of 78 battery-operated electric hybrid boats plying along 38 terminals and 16 routes spanning 76 kilometres.[402] It is integrated with the Kochi Metro and serves as a feeder service to the suburbs along the rivers where transport accessibility is limited.[403]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 6,396,262 | — |

| 1911 | 7,147,673 | +11.7% |

| 1921 | 7,802,127 | +9.2% |

| 1931 | 9,507,050 | +21.9% |

| 1941 | 11,031,541 | +16.0% |

| 1951 | 13,549,118 | +22.8% |

| 1961 | 16,903,715 | +24.8% |

| 1971 | 21,347,375 | +26.3% |

| 1981 | 25,453,680 | +19.2% |

| 1991 | 29,098,518 | +14.3% |

| 2001 | 31,841,374 | +9.4% |

| 2011 | 33,406,061 | +4.9% |

| Source: Census of India[404] | ||

Kerala is home to 2.8% of India's population; with a density of 859 persons per km2, its land is nearly three times as densely settled as the national average of 370 persons per km2.

Largest cities or towns in Kerala

2011 Census of India[406] As per the population within their respective Municipal Corporation/Municipality limits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rank

|

District

|

Pop.

|

|||||||

Thiruvananthapuram  Kozhikode |

1 | Thiruvananthapuram | Thiruvananthapuram district | 968,990 |  Kochi  Kollam | ||||

| 2 | Kozhikode | Kozhikode district | 609,224 | ||||||

| 3 | Kochi | Ernakulam district | 602,046 | ||||||

| 4 | Kollam | Kollam district | 388,288 | ||||||

| 5 | Thrissur | Thrissur district | 315,957 | ||||||

| 6 | Kannur | Kannur district | 232,486 | ||||||

| 7 | Alappuzha | Alappuzha district | 180,856 | ||||||

| 8 | Kottayam | Kottayam district | 138,283 | ||||||

| 9 | Palakkad | Palakkad district | 131,019 | ||||||

| 10 | Manjeri | Malappuram district | 97,102 | ||||||

Gender

There is a tradition of matrilineal inheritance in Kerala, where the mother is the head of the household.[409] As a result, women in Kerala have had a much higher standing and influence in the society. This was common among certain influential castes and is a factor in the value placed on daughters. Christian missionaries also influenced Malayali women in that they started schools for girls from poor families.[410] Opportunities for women such as education and gainful employment often translate into a lower birth rate,[411] which in turn, make education and employment more likely to be accessible and more beneficial for women. This creates an upward spiral for both the women and children of the community that is passed on to future generations. According to the Human Development Report of 1996, Kerala's Gender Development Index was 597; higher than any other state of India. Factors, such as high rates of female literacy, education, work participation and life expectancy, along with favourable sex ratio, contributed to it.[412]

Kerala's sex ratio of 1.084 (females to males) is higher than that of the rest of India; it is the only state where women outnumber men.[291]: 2 While having the opportunities that education affords them, such as political participation, keeping up to date with current events, reading religious texts etc., these tools have still not translated into full, equal rights for the women of Kerala. There is a general attitude that women must be restricted for their own benefit. In the state, despite the social progress, gender still influences social mobility.[413][414][415]

LGBT rights

Kerala has been at the forefront of LGBT issues in

In June 2019, the Kerala government passed a new order that members of the transgender community should not be referred to as the "third gender" or "other gender" in government communications. Instead, the term "transgender" should be used. Previously, the gender preferences provided in government forms and documents included male, female, and other/third gender.[422][423]

In the 2021 Mathrubhumi Youth Manifesto Survey conducted on people aged between 15 and 35, majority (74.3%) of the respondents supported legislation for same-sex marriage while 25.7% opposed it.[424]

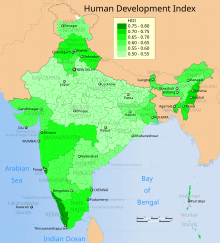

Human Development Index

Under a democratic communist local government, Kerala has achieved a record of social development much more advanced than the Indian average.

According to the 2011 census, Kerala has the highest

Kerala has undergone a "

In 2004, the birthrate was low at 18 per 1,000.

In 2015, Kerala had the highest conviction rate of any state, over 77%.

Healthcare

Kerala is a pioneer in implementing the

The

In 2014, Kerala became the first state in India to offer free cancer treatment to the poor, via a program called Sukrutham.[470] People in Kerala experience elevated incidence of cancers, liver and kidney diseases.[471] In April 2016, the Economic Times reported that 250,000 residents undergo treatment for cancer. It also reported that approximately 150 to 200 liver transplants are conducted in the region's hospitals annually. Approximately 42,000 cancer cases are reported in the region annually. This is believed to be an underestimate as private hospitals may not be reporting their figures. Long waiting lists for kidney donations has stimulated illegal trade in human kidneys, and prompted the establishment of the Kidney Federation of India which aims to support financially disadvantaged patients.[472] As of 2017–18, there are 6,691 modern medicine institutions under the department of health services, of which the total bed strength is 37,843; 15,780 in rural areas and 22,063 in urban.[473]

Language

Malayalam is the official language of Kerala,[475] and one of the six Classical languages of India.[476] There is a significant Tamil population throughout Kerala mainly in Idukki district and Palakkad district which accounts for 17.48% and 4.8% of its total population.[477] Tulu and Kannada are spoken mainly in the northern parts of Kasaragod district, each of which account for 8.77% and 4.23% of total population in the district, respectively.[477][478]

Religion

Religion in Kerala (2011)[479]

Kerala is very religiously diverse with

The mythological legends regarding the origin of Kerala are Hindu in nature. Kerala produced several saints and movements.

Islam arrived in Kerala, a part of the larger

According to some scholars, the Mappilas are the oldest settled Muslim community in South Asia.

Ancient Christian tradition says that Christianity reached the shores of Kerala in 52 CE with the arrival of

Buddhism was popular in the time of Ashoka

Education

The

According to the first economic census, conducted in 1977, 99.7% of the villages in Kerala had a primary school within 2 kilometres (1.2 mi), 98.6% had a middle school within 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) and 96.7% had a high school or higher secondary school within 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).[88]: 62 In 1991, Kerala became the first state in India to be recognised as completely literate, although the effective literacy rate at that time was only 90%.[544] In 2006–2007, the state topped the Education Development Index (EDI) of the 21 major states in India.[545] As of 2007[update], enrolment in elementary education was almost 100%; and, unlike other states in India, educational opportunity was almost equally distributed among sexes, social groups, and regions.[546] According to the 2011 census, Kerala has a 93.9% literacy, compared to the national literacy rate of 74.0%.[434] In January 2016, Kerala became the first Indian state to achieve 100% primary education through its Athulyam literacy programme.[547]

The educational system prevailing in the state's schools specifies an initial 10-year course of study, which is divided into three stages: lower primary, upper primary, and secondary school—known as 4+3+3, which signifies the number of years for each stage.

The

The

Culture

The culture of Kerala is composite and cosmopolitan in nature and it is an integral part of

Festivals

Many of the temples in Kerala hold festivals on specific days of the year.

Music and dance

Kerala is home to a number of

Cinema

Literature

The

Cuisine

Kerala cuisine includes a wide variety of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes prepared using fish, poultry, and meat. Culinary spices have been cultivated in Kerala for millennia and they are characteristic of its cuisine.

Elephants

Elephants have been an integral part of the culture of the state. Almost all of the local festivals in Kerala include at least one richly caparisoned elephant. Kerala is home to the largest domesticated population of elephants in India—about 700

Media

The media, telecommunications, broadcasting and cable services are regulated by the

Sports

By the 21st century, almost all of the native sports and games from Kerala have either disappeared or become just an art form performed during local festivals; including

Among the prominent athletes hailing from the state are

For the 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup in India, the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium (Kochi), was chosen as one of the six venues where the game would be hosted in India.[684] Greenfield International Stadium at located at Kariavattom in Thiruvananthapuram city, is India's first DBOT (design, build, operate and transfer) model outdoor stadium and it has hosted international cricket matches and international football matches including 2015 SAFF Championship.[685]

Tourism

Kerala's culture and traditions, coupled with its varied

Kerala's beaches, backwaters, lakes, mountain ranges, waterfalls, ancient ports, palaces, religious institutions[693] and wildlife sanctuaries are major attractions for both domestic and international tourists.[694] The city of Kochi ranks first in the total number of international and domestic tourists in Kerala.[695][696] Until the early 1980s, Kerala was a relatively unknown destination compared to other states in the country.[697] In 1986 the government of Kerala declared tourism an important industry and it was the first state in India to do so.[698] Marketing campaigns launched by the Kerala Tourism Development Corporation, the government agency that oversees the tourism prospects of the state, resulted in the growth of the tourism industry.[699] Many advertisements branded Kerala with the tagline Kerala, God's Own Country.[699] Kerala tourism is a global brand and regarded as one of the destinations with highest recall.[699] In 2006, Kerala attracted 8.5 million tourists, an increase of 23.7% over the previous year, making the state one of the fastest-growing popular destinations in the world.[700] In 2011, tourist inflow to Kerala crossed the 10-million mark.[701]

Ayurvedic tourism has become very popular since the 1990s, and private agencies have played a notable role in tandem with the initiatives of the Tourism Department.[697] Kerala is known for its ecotourism initiatives which include mountaineering, trekking and bird-watching programmes in the Western Ghats as the major activities.[702] The state's tourism industry is a major contributor to the state's economy, growing at the rate of 13.3%.[703] The revenue from tourism increased five-fold between 2001 and 2011 and crossed the ₹ 190 billion mark in 2011. According to the Economic Times[704] Kerala netted a record revenue of INR 365280.1 million from the tourism sector in 2018, clocking an increase of Rs 28743.3 million from the previous year. Over 16.7 million tourists visited Kerala in 2018 as against 15.76 million the previous year, recording an increase of 5.9%. The industry provides employment to approximately 1.2 million people.[701]

The state's only drive-in beach,

See also

- Outline of Kerala

- South India

- Dravidian people

References

Citations

- ^ "Kerala Physiography | Geographical location | Kerala | Kerala". Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Anamudi – Peakbagger.com". www.peakbagger.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Kuttanadan.com : Explore the Rice Bowl of Kerala". Kuttanadan Website. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2018 (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala. 2020. p. 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "52nd report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2014 to June 2015)" (PDF). Ministry of Minority Affairs (Government of India). 29 March 2016. p. 132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017.

- from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ ":: FINANCE DEPARTMENT :: GOVERNMENT OF KERALA". finance.kerala.gov.in. Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Sub-national HDI – Area Database". Global Data Lab. Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Literacy Survey, India (2017–18)". Firstpost. 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "State Symbols of India". ENVIS Centre on Wildlife & Protected Areas. 1 December 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Jacob, Aneesh. "'Budha Mayoori' to be named Kerala's state butterfly". Mathrubhumi. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Jackfruit to be Kerala's state fruit; declaration on March 21". The Indian Express. PTI. 17 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126415885. Archivedfrom the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956" (PDF). legislative.gov.in. Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Kerala – Principal Language". Government of India. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Subramanian, Archana (December 2016). "Route it through the seas". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ SDG India Index 2021–22 (3 June 2022). "SDGs India Index". Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy. Table 154 : Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line. (2011-12)". Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Level of Urbanisation in Indian States". mohua.gov.in. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India.

- ^ Gireesh Chandra Prasad (30 December 2019). "Kerala tops sustainable development goals index". Livemint. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "MOSPI State Domestic Product, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India". 15 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Government of Kerala (2021). Economic Review 2020 – Volume I (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala State Planning Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Kerala: A vacation in paradise". The Times of India. 7 February 2014. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ P. C. Alexander. Buddhism in Kerala. p. 23.

- ^ Nicasio Silverio Sainz (1972). Cuba y la Casa de Austria. Ediciones Universal. p. 120. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ John R. Marr (1985). The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literature. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 263.

- ISBN 978-1-4438-6190-8.

- ISBN 978-8176481700.

- ISBN 978-0-12-375689-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126419036. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-3447025225.

- ^ Who's Who in Madras 1934

- ISBN 978-8120601178. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ J. Sturrock (1894). "Madras District Manuals – South Canara (Volume-I)". Madras Government Press.

- ^ V. Nagam Aiya (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press.

- ^ C. A. Innes and F. B. Evans, Malabar and Anjengo, volume 1, Madras District Gazetteers (Madras: Government Press, 1915), p. 2.

- ^ M. T. Narayanan, Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar (New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 2003), xvi–xvii.

- ^ Mohammad, K.M. "Arab relations with Malabar Coast from 9th to 16th centuries" Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. 60 (1999), pp. 226–34.

- ^ ISBN 978-8120604476.

- ISBN 978-81-206-0446-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126421992.

- ^ Ancient Indian History By Madhavan Arjunan Pillai, p. 204 [ISBN missing]

- ^ S.C. Bhatt, Gopal K. Bhargava (2006) "Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: Volume 14.", p. 18

- ^ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–12. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ISBN 978-8120601451.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5325-4. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991255-1. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4179-4463-7. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ "Ophir" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Schroff, Wifred H. (1912), The Periplus of the Erythræan Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean, New York: Longmans, Green, and Company, p. 41

- ^ Smith, William, A dictionary of the Bible, Hurd and Houghton, 1863 (1870), p. 1441

- ^ "Peacock – Easton's Bible Dictionary Online". biblestudytools.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Ramaswami, Sastri, The Tamils and their culture, Annamalai University, 1967, p. 16

- ^ Gregory, James, Tamil lexicography, M. Niemeyer, 1991, p. 10

- ^ Fernandes, Edna, The last Jews of Kerala, Portobello, 2008, p. 98

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition, Volume I Almug Tree Almunecar→ALMUG or ALGUM TREE. The Hebrew words Almuggim or Algummim have translated Almug or Algum trees in our version of the Bible (see 1 Kings x. 11, 12; 2 Chron. ii. 8, and ix. 10, 11). The wood of the tree was very precious, and was brought from Ophir (probably some part of India), along with gold and precious stones, by Hiram, and was used in the formation of pillars for the temple at Jerusalem, and for the king's house; also for the inlaying of stairs, as well as for harps and psalteries. It is probably the red sandal-wood of India (Pterocarpus santalinus). This tree belongs to the natural order Leguminosæ, sub-order Papilionaceæ. The wood is hard, heavy, close-grained, and of fine red colour. It is different from the white fragrant sandal-wood, which is the produce of Santalum album, a tree belonging to a distinct natural order. Also, see notes by George Menachery in the St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, Vol. 2 (1973)

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967), A Survey of Kerala History, Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society [Sales Department]; National Book Stall, p. 58, archived from the original on 25 November 2023, retrieved 31 January 2021

- ISBN 978-8120618503

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 31–32.

- ^ Kesavan Veluthat, 'The Keralolpathi as History', in The Early Medieval in South India, New Delhi, 2009, pp. 129–46.

- ^ a b Noburu Karashima (ed.), A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014. 146–47.

- ^ a b c Frenz, Margret. 2003. 'Virtual Relations, Little Kings in Malabar', in Sharing Sovereignty. The Little Kingdom in South Asia, eds Georg Berkemer and Margret Frenz, pp. 81–91. Berlin: Zentrum Moderner Orient.

- ^ a b c Logan, William. Malabar. Madras: Government Press, Madras, 1951 (reprint). 223–40.

- ISBN 978-1-136-70491-8. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-9385505638. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-8190250511. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-136-70491-8. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ISBN 817648170-X, archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023, retrieved 31 January 2021

- ^ a b Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. p. 98. [ISBN missing]

- ^ History of Travancore by Shangunny Menon, page 63

- ^ Nainar, S. Muhammad Hussain (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ISBN 817648170X, archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023, retrieved 31 January 2021

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Unlocking the secrets of history". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 December 2004. Archived from the original on 26 January 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8177552577. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Wayanad". kerala.gov.in. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Pradeep Kumar, Kaavya (28 January 2014). "Of Kerala, Egypt, and the Spice link". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-8180692949. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-60520-492-5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 193. GGKEY:2W0QHXZ7K40. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8172110598. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120601505. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ a b Subramanian, T. S (28 January 2007). "Roman connection in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131716779. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-9380607344.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 385.

- ISBN 978-0-8196-0143-8. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India, Yogesh Sharma, Primus Books 2010

- ISBN 978-8170418597. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8172110529. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334–350.

- ^ "Ancient History Sourcebook: Pliny: Natural History 6.96-111. (On India)". 6 November 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013.

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Archived 27 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- ^ Joseph Minattur. "Malaya: What's in the name" (PDF). siamese-heritage.org. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-8170990260. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120601451. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-8120601451. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ ISBN 978-9652781796.

- ^ David D'Beth Hillel (1832). The Travels of Rabbi David D'Beth Hillel: From Jerusalem, Through Arabia, Koordistan, Part of Persia, and Indudasam (India) to Madras. author. p. 135.

- ISBN 978-0-8371-2615-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0802824172.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ *Bindu Malieckal (2005) Muslims, Matriliny, and A Midsummer Night's Dream: European Encounters with the Mappilas of Malabar, India; The Muslim World Volume 95 Issue 2

- ISBN 978-0-521-21258-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-89103-5. Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7656-0104-9. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-520-21323-4. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-8120811584. Archivedfrom the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ M. T. Narayanan (2003). Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar. Northern Book Centre.

- ^ a b K. Balachandran Nayar (1974). In quest of Kerala. Accent Publications. p. 86. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-136-10084-0.

- ^ "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218, archived from the original on 24 August 2023, retrieved 9 June 2021

- ^ R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ISBN 9788126419395.

- ^ Razak, Abdul (2013). Colonialism and community formation in Malabar: a study of Muslims of Malabar.

- ^ ISBN 978-9004079298. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171545797. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "The Buddhist History of Kerala". Kerala.cc. Archived from the original on 21 March 2001. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800. Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew (2001). Edited by: Pius Malekandathil and T. Jamal Mohammed. Fundacoa Oriente. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR (Kerala)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- ^ a b c d Varier, M. R. Raghava. "Documents of Investiture Ceremonies" in K. K. N. Kurup, Edit., "India's Naval Traditions". Northern Book Centre, New Delhi, 1997

- ^ Ibn Battuta, H. A. R. Gibb (1994). The Travels of Ibn Battuta A.D 1325–1354. Vol. IV. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 9748496783

- ^ Varthema, Ludovico di, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, A.D.1503–08, translated from the original 1510 Italian ed. by John Winter Jones, Hakluyt Society, London

- ^ Gangadharan. M., The Land of Malabar: The Book of Barbosa (2000), Vol II, M.G University, Kottayam.

- ISBN 978-1-56836-249-6.

- ISBN 978-9057024535. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-521-26931-5.

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- ^ Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Reprint. Asian Educational Services. pp. 19–47.

- ^ "Kollam – Kerala Tourism". Kerala Tourism. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Kollam Mayor inspects Tangasseri Fort". The Hindu. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Singh, Arun Kumar (11 February 2017). "Give Indian Navy its due". The Asian Age. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ a b A. Sreedhara Menon. Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books (2011)

- ^ A G Noorani. Islam in Kerala. Books [1] Archived 19 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Roland E. Miller. Mappila Muslim Culture SUNY Press, 2015

- ISBN 978-8172110833. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120615243. Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "A Portion of Kasaragod's Bekal Forts Observation Post Caves in". The Hindu. 12 August 2019. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Sanjay Subrahmanyam. "The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500–1650". Cambridge University Press, 2002

- ISBN 978-1-85743-318-0. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "How the Portuguese used Hindu-Muslim wars – and Christianity – for the bloody conquest of Goa". Dailyo.in. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ a b M K Sunil Kumar (26 September 2017). "50 years on, Kochi still has a long way to go". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-8172110529. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-9004168169. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8185381428. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-9073782921. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8126421565. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "The Territories and States of India" (PDF). Europa. 2002. pp. 144–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press. p. 451.

- ^ a b c d "History of Mahé". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ISBN 978-8187139690. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-2424-7. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131758304. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ The Edinburgh Gazetteer. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1827. pp. 63–. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Dharma Kumar (1965). Land and Caste in South India: Agricultural Labor in the Madras Presidency During the Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. pp. 87–. GGKEY:T72DPF9AZDK. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8170170341. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Superintendent of Government Printing (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India (Provincial Series): Madras. Calcutta: Government of India. p. 22. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- International Labour Office. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Chronological List of Central Acts (Updated up to 17-10-2014)". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ a b Lewis McIver, G. Stokes (1883). Imperial Census of 1881 Operations and Results in the Presidency of Madras ((Vol II) ed.). Madras: E.Keys at the Government Press. p. 444. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b Presidency, Madras (India (1915). Madras District Gazetteers, Statistical Appendix For Malabar District (Vol.2 ed.). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press. p. 20. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b Henry Frowde, M.A., Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908–1909). Imperial Gazetteer of India (New ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ KP Saikiran (10 October 2020). "Beating the retreat: The Malabar Special Police is no longer the trigger-happy unit". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ISBN 978-9004113718. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Tottenham GRF (ed), The Mappila Rebellion 1921–22, Govt Press Madras 1922 P 71

- ISBN 978-9004045101. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-14-310274-8. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-520-04667-2. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-74179-155-6. Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ K.G. Kumar (12 April 2007). "50 years of development". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-203-96774-4. Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-8170248361. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 8 June 2008

- ^ "Physical and Anatomical Characteristic of Wood of Some Less-Known Tree Species of Kerala" (PDF). Kerala Forest Research Institute. Government of Kerala. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Marine Fisheries". fisheries.kerala.gov.in. Department of Fisheries, Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8185880501. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Geological Survey Water-supply Paper. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1961. p. 4. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-8183563260. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-74196-438-7. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8170999133. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Pratiyogita Darpan (September 2006). Pratiyogita Darpan. Pratiyogita Darpan. p. 72. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8174781642. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Chandran Nair, Dr.S.Sathis. "India – Silent Valley Rainforest Under Threat Once More". rainforestinfo.org.au. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8183241298. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-07-066772-3. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Hunter, William Wilson; James Sutherland Cotton; Richard Burn; William Stevenson Meyer; Great Britain India Office (1909). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. 11. Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b "UN designates Western Ghats as world heritage site". The Times of India. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ a b "The Times of India: Latest News India, World & Business News, Cricket & Sports, Bollywood". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ William Logan (1887). Malabar Manual (Volume-II). Madras Government Press.

- ^ "Mineral Resources". Department of Mining and Geology – Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b Chandran 2018, p. 343.

- PMID 19066487.

- ISBN 978-0-415-77336-2. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131767344. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Press Trust of India (1 June 2020). "Kerala Boat Ferries Lone Passenger To Help Her Take Exam". NDTV. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Suchitra, M (13 August 2003). "Thirst below sea level". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-07-070288-2. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI—Ministry of Shipping) (2005). "Introduction to Inland Water Transport". IWAI (Ministry of Shipping). Archived from the original on 4 February 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2006.

- ISBN 978-8171885947.

- from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ISBN 978-9048124978. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Baynes, Chris (15 August 2018). "Worst floods in nearly a century kill 44 in India's Kerala state amid torrential monsoon rains". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-8183320818. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8181373991. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131758304. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120914667. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-74179-155-6. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ S.V. Jeevananda Reddy. Climate Change: Myths and Realities. Jeevananda Reddy. p. 71. GGKEY:WDFHBL1XHK3. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120333383. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Hydromet Division Updated/Real Time Maps". India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Brenkert, A.; Malone, E. (2003). "Vulnerability and resilience of India and Indian states to climate change: a first-order approximation". Joint Global Change Research Institute.

- ^ a b Sudha, T. M. "Opportunities in participatory planning to Evolve a Landuse Policy for Western Ghats Region in Kerala" (PDF). Department of Town and Country Planning, Kerala. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ "History". Kerala forests and wildlife department. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Sreedharan TP (2004). "Biological Diversity of Kerala: A survey of Kalliasseri panchayat, Kannur district" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ Chandran 2018, p. 342.

- ^ Chandran 2018, p. 347.

- ^ Jayarajan M (2004). "Sacred Groves of North Malabar" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-470-75683-6. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8180697746. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-9004168190. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "World's oldest teak trees dying in Kerala". DNA India. 13 May 2009. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "View of A checklist of the vertebrates of Kerala State, India | Journal of Threatened Taxa". threatenedtaxa.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016.

- ISBN 978-8185041544. Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Local Self Government Institutions | Deparyment of Panchayats". dop.lsgkerala.gov.in. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ "Revenue Guide 2018" (PDF). Government of Kerala. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Revenue department, government of Kerala". Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Local Self Governance in Kerala". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ISBN 978-3-642-27618-7. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8177648713. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Thiruvananthapuram". 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2022. Year of becoming a corporation

- ^ Kozhikode Lok Sabha constituency redrawn Delimitation impact, The Hindu 5 February 2008

- ^ "Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project". Local Self Government Department. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "City Information". Cochin International Airport. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Cities best to earn a living are not the best to live: Survey". The Times of India. 26 November 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "History of Kerala Legislature". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Our Parliament". Parliamentofindia.nic.in. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Responsibilities". Kerala Rajbhavan. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8180696220. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "History of Judiciary". All-India Judges Association. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-16-086824-5. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "High Court of Kerala Profile". High Court of Kerala. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8177648720. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120332461. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b Mariamma Sanu George. "An Introduction to local self governments in Kerala" (PDF). SDC CAPDECK. pp. 17–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ S M Vijayanand (April 2009). "Kerala – A Case Study of Classical Democratic Decentralisation" (PDF). Kerala Institute of Local Administration. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7619-3467-7. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ S M Vijayanand (April 2009). "Kerala – A Case Study of Classical Democratic Decentralisation" (PDF). Kerala Institute of Local Administration. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-1607-6.

- ^ India Corruption Survey 2019 – Report (PDF). Transparency International India. 2019. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Special currespondent (28 February 2016). "Kerala the first digital State". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ PTI (30 October 2020). "Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Goa best governed States: report". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Kerala Government – Legislature". Government of kerala. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "National and State Income". Kerala State Planning Board. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "Top 5 districts of Kerala on the basis of GDP at current price from 2004–05 to 2012–13". Government of India. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Heller, Patrick (18 April 2020). "A virus, social democracy, and dividends for Kerala". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Gross State Domestic Product of Kerala". Department of Economics and Statistics, Govt. of Kerala. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b Mohindra KS (2003). "A report on women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in Kerala state, India: a public health perspective". Université de Montréal Department de Medicine Social et Prévention.

- ^ "Economy – Kerala – States and Union Territories – Know India: National Portal of India". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Provisional results of economic census 2005" (PDF). Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Varma MS (4 April 2005). "Nap on HDI scores may land Kerala in an equilibrium trap". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d Tharamangalam J (2005). "The Perils of Social Development without Economic Growth: The Development Debacle of Kerala, India" (PDF). Political Economy for Environmental Planners. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "Economy of Kerala – 2016". slbckerala.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d Chandran 2018, p. 409.

- ^ K.P. Kannan; K.S. Hari (2002). Kerala's Gulf connection: Emigration, remittances and their macroeconomic impact, 1972–2000. Research Papers in Economics (Report). Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Govind, Biju. "GCC residency cap may force lakhs to return". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Remittances: Kerala drives dollar flows to India". Yahoo! Finance. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "NRI deposits in Kerala banks cross Rs 1 lakh crore". The Times of India. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8171885947.

- ^ a b "New Evidences from the Kerala Migration Survey, 2018". Economic and Political Weekly. 55 (4): 7–8. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Migrant worker population in Kerala touches 2.5 m". Business Line. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Economic Survey 2011–12 Union Budget" (PDF). Government of India. 10 March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b Balachandran PG (2004). "Constraints on Diffusion and Adoption of Agro-mechanical Technology in Rice Cultivation in Kerala" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ a b Government of Kerala (2005). "Kerala at a Glance". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 22 January 2006.

- ^ a b Joy CV (2004). "Small Coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "State/Union Territory-Wise Number of Branches of Scheduled Commercial Banks and Average Population Per Bank Branch" (PDF). Reserve Bank of India. March 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "Now, you can bank on every village in Kerala". The Times of India. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ Kumar KG (8 October 2007). "Jobless no more?". Business Line. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

A study by K.C. Zacharia and S. Irudaya Rajan, two economists at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), unemployment in Kerala has dropped from 19.1[%] in 2003 to 9.4[%] in 2007.

- ISBN 978-8187621751. Archived(PDF) from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ Mary, John (12 May 2008). "Men (Not) At Work". Outlook. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "On May Day, Kerala becomes Nokkukooli-free". The Hindu. 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b Deaton, Angus (22 August 2003). Regional poverty estimates for India, 1999–2000 (PDF) (Report). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Budget In Brief" (PDF). finance.kerala.gov.in. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Memoranda from States: Kerala" (PDF). fincomindia.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Kerala: Hartals Own Country? Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 6 July 2008

- ^ "India Today On Cm". Keralacm.gov.in. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Big push for infrastructure in Budget". The Hindu. 3 March 2017 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ "Kerala Budget: Infrastructure projects get a major fillip". The New Indian Express. 4 March 2017.

- ^ "Modi to address heads of civic bodies on urban revamp". The Hindu. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ R. Ramabhadran, Pillai. "AMRUT to roll out on a smaller scale". The Hindu. No. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Shopping festival begins". The Hindu. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "LuLu Group: Going places". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Heller, Patrick; Törnquist, Olle (13 December 2021). "Making sense of Kerala". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

Kerala has specific challenges: persistently high levels of unemployment that disproportionately impact educated women, a high degree of global exposure and a very fragile environment. More broadly, as the 21st century unfolds, it becomes increasingly clearer that the role of the State in supporting development must fundamentally change. First, in highly educated societies like Kerala, industrialisation is no longer the path to economic prosperity.

- ISBN 978-8177081435.

- ^ "Indian Coir Industry". Indian Mirror. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ SIDBI Report on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Sector, 2010. Small Industries Development Bank of India. 2010.

- ^ N. Rajeevan (March 2012). "A Study on the Position of Small and Medium Enterprises in Kerala vis a vis the National Scenario". International Journal of Research in Commerce, Economics and Management. 2 (3).

- ^ "Functions, KSIDC, Thiruvananthapuram". Kerala State Industrial Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ISBN 978-8176254106. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8180696602. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Chandran 2018, p. 406.

- ^ Limca Book of Records. Bisleri Beverages Limited. 2001. p. 97. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-318-0. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Economic Affairs. H. Roy. 1998. p. 47. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4761-2308-0. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8189422486. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-07-015256-4. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8189422493. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7453-1693-2. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Cashew sector in a tailspin". The Hindu. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ a b Chandran 2018, p. 407.

- ISBN 978-9061935568. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-905226-85-6. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8170998761. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8179680568. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171641253. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product of Kerala and India From 2004–05 to 2012–13" (PDF). ecostat.kerala.gov.in. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ K. A. Martin (19 October 2014). "State to switch fully to organic farming by 2016: Mohanan". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "CM: Will Get Total Organic Farming State Tag by 2016". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-60358-050-2.

- ^ "Kerala: Natural Resources". Government of India. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Kerala: April 2012" (PDF). Indian Brand Equity Fund. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ India. Planning Commission (1961). Third five year plan. Manager of Publications. p. 359. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171885947. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-537028-7.

- ISBN 978-9221036265. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Journal of Kerala Studies. University of Kerala. 1987. p. 201. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b Ministry Annual Report (2019–20) (PDF). New Delhi: Ministry of Road Transport & Highways Transport Research Wing, Government of India. 2020.

- ^ Basic Road Statistics of India (2016–17) (PDF). New Delhi: Ministry of Road Transport & Highways Transport Research Wing, Government of India. 2019. pp. 7–18.

- ^ a b Chandran 2018, p. 422.

- ^ a b "National Highways in Kerala". Kerala Public Works Department. Government of Kerala. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Coastal, Hill Highways to become a reality". The Hindu. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "District of Palakkad – the granary of Kerala, Silent Valley National Park, Nelliyampathy". keralatourism.org. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "About us". Kerala Public Works Department. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Kumar VS (20 January 2006). "Kerala State transport project second phase to be launched next month". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Kumar VS (2003). "Institutional Strengthening Action Plan (ISAP)". Kerala Public Works Department. Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Kumar KG (22 September 2003). "Accidentally notorious". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ "Kerala parties finally toe NHAI line of 45-m wide highways". Indian Express. 18 August 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Check out India's 13 super expressways". Rediff.com. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Special Correspondent (28 March 2013). "Kerala against development of five NHs". The Hindu. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Staff Reporter (30 June 2013). "State's troubled highways a shocking revelation for Centre". The Hindu. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "All about KSRTC". Keralartc.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "KeralaRTC Official Website". www.keralartc.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ISBN 978-8170995562.

- ^ a b Chandran 2018, p. 423.

- ^ "Introduction" (PDF). Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "The Zonal Dream Of Railway Kerala". yentha.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S. Anil (29 December 2012). "'Lifeline' of Malabar turns 125". The Hindu. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "ആ ചൂളംവിളി പിന്നെയും പിന്നെയും..." Mathrubhumi. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "RailKerala". Trainweb. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b "The Nilambur news". Kerala Tourism. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Metro rail: DMRC demands prompt handing over of land, funds". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ "DMRC sets early deadline for Kochi Metro rail project". The Times of India. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "Alstom's new Metropolis train set for Kochi Metro". The Economic Times. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Alstom's Metropolis for Kochi – design unveiled for the first time". www.alstom.com. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Metro train to ply every 5 minutes, carry 1,000 persons". The Hindu. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Paul, John L. (20 February 2017). "India's first CBTC metro system to be ready in March". The Hindu. Kochi. Retrieved 20 January 2018.