Glyphosate: Difference between revisions

WP:ENGVAR issues that snuck in since the last time this came up. |

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers 71,078 edits m del stray space |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Glyphosate''' ([[IUPAC name]]: '''''N''-(phosphonomethyl)glycine''') is a broad-spectrum [[Herbicide|systemic herbicide]] and [[Crop desiccation|crop desiccant]]. It is an [[organophosphorus compound]], specifically a [[phosphonate]], which acts by inhibiting the plant enzyme [[5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase]]. It is used to kill [[weed]]s, especially annual [[Forbs|broadleaf weeds]] and grasses that compete with [[crop]]s. It was discovered to be an |

'''Glyphosate''' ([[IUPAC name]]: '''''N''-(phosphonomethyl)glycine''') is a broad-spectrum [[Herbicide|systemic herbicide]] and [[Crop desiccation|crop desiccant]]. It is an [[organophosphorus compound]], specifically a [[phosphonate]], which acts by inhibiting the plant enzyme [[5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase]]. It is used to kill [[weed]]s, especially annual [[Forbs|broadleaf weeds]] and grasses that compete with [[crop]]s. It was discovered to be an<!-- Please do not change "an" to "a". This page uses US English. --> herbicide by [[Monsanto]] chemist [[John E. Franz]] in 1970. Monsanto brought it to market for agricultural use in 1974 under the trade name '''[[Roundup (herbicide)|Roundup]]'''. Monsanto's last commercially relevant United States [[patent]] expired in 2000. |

||

Farmers quickly adopted glyphosate for agricultural weed control, especially after Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant [[Roundup Ready crops]], enabling farmers to kill weeds without killing their crops. In 2007, glyphosate was the most used herbicide in the United States' agricultural sector and the second-most used (after [[2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid|2,4-D]]) in home and garden, government and industry, and commercial applications.<ref name="EPAusage">United States EPA 2007 Pesticide Market Estimates [http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_2.htm#3_6 Agriculture], [http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_3.htm#3_7 Home and Garden]</ref> From the late 1970s to 2016, there was a 100-fold increase in the frequency and volume of application of [[glyphosate-based herbicides]] (GBHs) worldwide, with further increases expected in the future, partly in response to the global emergence and spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds.<ref name="biomedcentral_2016" />{{rp|1}} |

Farmers quickly adopted glyphosate for agricultural weed control, especially after Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant [[Roundup Ready crops]], enabling farmers to kill weeds without killing their crops. In 2007, glyphosate was the most used herbicide in the United States' agricultural sector and the second-most used (after [[2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid|2,4-D]]) in home and garden, government and industry, and commercial applications.<ref name="EPAusage">United States EPA 2007 Pesticide Market Estimates [http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_2.htm#3_6 Agriculture], [http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_3.htm#3_7 Home and Garden]</ref> From the late 1970s to 2016, there was a 100-fold increase in the frequency and volume of application of [[glyphosate-based herbicides]] (GBHs) worldwide, with further increases expected in the future, partly in response to the global emergence and spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds.<ref name="biomedcentral_2016" />{{rp|1}} |

||

Revision as of 00:02, 20 March 2019

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine

| |

| Other names

[(phosphonomethyl)amino]acetic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.012.726 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

RTECS number

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties[1] | |

| C3H8NO5P | |

| Molar mass | 169.073 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.704 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | 184.5 °C (364.1 °F; 457.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 187 °C (369 °F; 460 K) decomposes |

| 1.01 g/100 mL (20 °C) | |

| log P | −2.8 |

| Acidity (pKa) | <2, 2.6, 5.6, 10.6 |

| Hazards[1][2] | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H318, H411 | |

| P273, P280, P305+P351+P338, P310, P501 | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | InChem MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Glyphosate (

Farmers quickly adopted glyphosate for agricultural weed control, especially after Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant

Glyphosate is absorbed through foliage, and minimally through roots, and transported to growing points. It inhibits a plant

While glyphosate and formulations such as Roundup have been approved by regulatory bodies worldwide, concerns about their effects on humans and the environment persist, and have grown as the global usage of glyphosate increases.[4][5] A number of regulatory and scholarly reviews have evaluated the relative toxicity of glyphosate as an herbicide. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment toxicology review in 2013 found that "the available data is contradictory and far from being convincing" with regard to correlations between exposure to glyphosate formulations and risk of various cancers, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).[6] A meta-analysis published in 2014 identified an increased risk of NHL in workers exposed to glyphosate formulations.[7]

In March 2015, the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as "probably carcinogenic in humans" (category 2A) based on epidemiological studies, animal studies, and in vitro studies.[5][8][9] In contrast, the European Food Safety Authority concluded in November 2015 that "the substance is unlikely to be genotoxic (i.e. damaging to DNA) or to pose a carcinogenic threat to humans", later clarifying that while carcinogenic glyphosate-containing formulations may exist, studies "that look solely at the active substance glyphosate do not show this effect."[10][11] The WHO and FAO Joint committee on pesticide residues issued a report in 2016 stating the use of glyphosate formulations does not necessarily constitute a health risk, and giving admissible daily maximum intake limits (one milligram/kg of body weight per day) for chronic toxicity.[12] The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) classified glyphosate as causing serious eye damage and toxic to aquatic life, but did not find evidence implicating it as a carcinogen, a mutagen, toxic to reproduction, nor toxic to specific organs.[13]

Discovery

Glyphosate was first synthesized in 1950 by Swiss chemist Henry Martin, who worked for the Swiss company

Somewhat later, glyphosate was independently discovered in the

Monsanto developed and patented the use of glyphosate to kill weeds in the early 1970s and first brought it to market in 1974, under the Roundup brandname.[22][23] While its initial patent[24] expired in 1991, Monsanto retained exclusive rights in the United States until its patent[25] on the isopropylamine salt expired in September 2000.[26]

In 2008, United States Department of Agriculture (

As of April 2017, the Canadian government stated that glyphosate was "the most widely used herbicide in Canada", at which date the product labels were revised to ensure a limit of 20% POEA by weight.[28]

Chemistry

Glyphosate is an aminophosphonic analogue of the natural amino acid

- PCl3 + H2CO → Cl2P(=O)-CH2Cl

- Cl2P(=O)-CH2Cl + 2 H2O → (HO)2P(=O)-CH2Cl + 2 HCl

- (HO)2P(=O)-CH2Cl + H2N-CH2-COOH → (HO)2P(=O)-CH2-NH-CH2-COOH + HCl

The main deactivation path for glyphosate is hydrolysis to aminomethylphosphonic acid.[30]

Synthesis

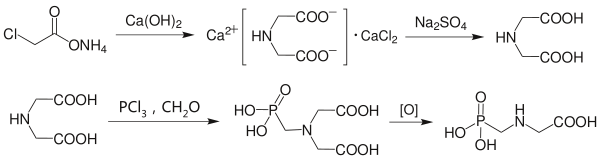

Two main approaches are used to synthesize glyphosate industrially. The first is to react

The chloroacetic acid approach is less efficient than other iminodiacetic acid approaches, owing to the production of calcium chloride waste and decreased yield. When hydrogen cyanide is readily available as a by-product (say), an alternative approach is to use iminodiacetonitrile, HN(CH2CN)2, and diethanolamine is also a suitable starting material.[14]

The second involves the use of

This synthetic approach is responsible for a substantial portion of the production of glyphosate in China, with considerable work having gone into recycling the triethylamine and methanol.[14] Progress has also been made in attempting to eliminate the need for triethylamine altogether.[31]

Impurities

Technical grade glyphosate is a white powder which, according to

Mode of action

Glyphosate interferes with the

Under normal circumstances, EPSP is

X-ray crystallographic studies of glyphosate and EPSPS show that glyphosate functions by occupying the binding site of the phosphoenolpyruvate, mimicking an intermediate state of the ternary enzyme–substrate complex.[43][44] Glyphosate inhibits the EPSPS enzymes of different species of plants and microbes at different rates.[45][46]

Uses

Glyphosate is effective in killing a wide variety of plants, including

Glyphosate and related herbicides are often used in

In many cities, glyphosate is sprayed along the sidewalks and streets, as well as crevices in between pavement where weeds often grow. However, up to 24% of glyphosate applied to hard surfaces can be run off by water.

In addition to its use as an herbicide, glyphosate is also used for crop desiccation (siccation) to increase harvest yield,[40] and as a result of desiccation, to increase sucrose concentration in sugarcane before harvest.[52] The application of glyphosate just before harvest on grains (like wheat, barley, and oats) kills the food crop so that it dries more quickly and evenly, similar to the use of desiccants.[53] This dry crop does not have to be windrowed (swathed and dried) prior to harvest, but can easily be straight-cut and harvested. This saves the farmer time and money, which is important in northern regions where the growing season is short.[54][55] Excess residue levels in beans resulting from incorrect application can render the crop unfit for sale.[56]

In 2003, Monsanto patented the use of glyphosate as an antiparasitic,[57] and in 2017 they marketed a Roundup formulation without glyphosate as a lawn herbicide.[58]

Genetically modified crops

Some micro-organisms have a version of 5-enolpyruvoyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthetase (EPSPS) resistant to glyphosate inhibition. A version of the enzyme that was both resistant to glyphosate and that was still efficient enough to drive adequate plant growth was identified by Monsanto scientists after much trial and error in an still under development.

In 2015, 89% of corn, 94% of soybeans, and 89% of cotton produced in the United States were genetically modified to be herbicide-tolerant.[62][clarification needed]

Formulations and tradenames

Glyphosate is marketed in the United States and worldwide by many

Glyphosate is an acid molecule, so it is formulated as a salt for packaging and handling. Various salt formulations include isopropylamine, diammonium, monoammonium, or potassium as the counterion. The active ingredient of the Monsanto herbicides is the isopropylamine salt of glyphosate. Another important ingredient in some formulations is the surfactant polyethoxylated tallow amine. Some brands include more than one salt. Some companies report their product as acid equivalent (ae) of glyphosate acid, or some report it as active ingredient (ai) of glyphosate plus the salt, and others report both. To compare performance of different formulations, knowledge of how the products were formulated is needed. Given that different salts have different weights, the acid equivalent is a more accurate method of expressing and comparing concentrations.

Adjuvant loading refers to the amount of adjuvant[71][72] already added to the glyphosate product. Fully loaded products contain all the necessary adjuvants, including surfactant; some contain no adjuvant system, while other products contain only a limited amount of adjuvant (minimal or partial loading) and additional surfactants must be added to the spray tank before application.[73]

Products are supplied most commonly in formulations of 120, 240, 360, 480, and 680 g/l of active ingredient. The most common formulation in agriculture is 360 g/l, either alone or with added

For 360 g/l formulations, European regulations allow applications of up to 12 l/ha for control of perennial weeds such as

Environmental fate

Glyphosate

The half-life of glyphosate in soil ranges between 2 and 197 days; a typical field half-life of 47 days has been suggested. Soil and climate conditions affect glyphosate's persistence in soil. The median half-life of glyphosate in water varies from a few to 91 days.[39] At a site in Texas, half-life was as little as three days. A site in Iowa had a half-life of 141 days.[80] The glyphosate metabolite AMPA has been found in Swedish forest soils up to two years after a glyphosate application. In this case, the persistence of AMPA was attributed to the soil being frozen for most of the year.[81] Glyphosate adsorption to soil, and later release from soil, varies depending on the kind of soil.[82][83] Glyphosate is generally less persistent in water than in soil, with 12- to 60-day persistence observed in Canadian ponds, although persistence of over a year has been recorded in the sediments of American ponds.[79] The half-life of glyphosate in water is between 12 days and 10 weeks.[84]

According to the National Pesticide Information Center fact sheet, glyphosate is not included in compounds tested for by the Food and Drug Administration's Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program, nor in the United States Department of Agriculture's Pesticide Data Program. However, a field test showed that lettuce, carrots, and barley contained glyphosate residues up to one year after the soil was treated with 3.71 lb of glyphosate per acre (4.15 kg per hectare).[39] The U.S. has determined the acceptable daily intake of glyphosate at 1.75 milligrams per kilogram of bodyweight per day (mg/kg/bw/day) while the European Union has set it at 0.5.[85][86]

Toxicity

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in herbicide formulations containing it. However, in addition to glyphosate salts, commercial formulations of glyphosate contain additives (known as adjuvants) such as surfactants, which vary in nature and concentration. Surfactants such as polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) are added to glyphosate to enable it to wet the leaves and penetrate the cuticle of the plants.

Glyphosate alone

Humans

The acute oral toxicity for mammals is low,[87] but death has been reported after deliberate overdose of concentrated formulations.[88] The surfactants in glyphosate formulations can increase the relative acute toxicity of the formulation.[89][90] In a 2017 risk assessment, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) wrote: "There is very limited information on skin irritation in humans. Where skin irritation has been reported, it is unclear whether it is related to glyphosate or co-formulants in glyphosate-containing herbicide formulations." The ECHA concluded that available human data was insufficient to support classification for skin corrosion or irritation.[91] Inhalation is a minor route of exposure, but spray mist may cause oral or nasal discomfort, an unpleasant taste in the mouth, or tingling and irritation in the throat. Eye exposure may lead to mild conjunctivitis. Superficial corneal injury is possible if irrigation is delayed or inadequate.[89]

Cancer

The

There is weak evidence human cancer risk might increase as a result of occupational exposure to large amounts of glyphosate, such as agricultural work, but no good evidence of such a risk from home use, such as in domestic gardening.[97] When weak statistical associations with cancer have been found, such observations have been attributed to bias and confounding in correlational studies due to workers often being exposed to other known carcinogens;[98] meta-analyses that show an effect between glyphosate use and non-Hodgkin lymphoma have been criticized for not assessing these factors, underlying quality of studies being reviewed, or whether the relationship is causal rather than only correlational.[98]

Other mammals

Amongst mammals, glyphosate is considered to have "low to very low toxicity". The

A review of unpublished short-term rabbit-feeding studies reported severe toxicity effects at 150 mg/kg/day and "

Glyphosate-based herbicides may cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mammals. Evidence also shows that such herbicides cause direct electrophysiological changes in the cardiovascular systems of rats and rabbits.[100]

Aquatic fauna

In many freshwater invertebrates, glyphosate has a 48-hour

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity of glyphosate has been described in the microbiology literature since its discovery in 1970 and the description of glyphosate's mechanism of action in 1972. Efficacy was described for numerous bacteria and fungi.[101] Glyphosate can control the growth of apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium falciparum (malaria), and Cryptosporidium parvum, and has been considered an antimicrobial agent in mammals.[102] Inhibition can occur with some Rhizobium species important for soybean nitrogen fixation, especially under moisture stress.[103]

Soil biota

When glyphosate comes into contact with the soil, it can be bound to soil particles, thereby slowing its degradation.[79][80] Glyphosate and its degradation product, aminomethylphosphonic acid are considered to be much more benign toxicologically and environmentally than most of the herbicides replaced by glyphosate.[105] A 2016 meta-analysis concluded that at typical application rates glyphosate had no effect on soil microbial biomass or respiration.[106] A 2016 review noted that contrasting effects of glyphosate on earthworms have been found in different experiments with some species unaffected, but others losing weight or avoiding treated soil. Further research is required to determine the impact of glyphosate on earthworms in complex ecosystems.[107]

Endocrine disruption

In 2007, the EPA selected glyphosate for further screening through its Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP). Selection for this program is based on a compound's prevalence of use and does not imply particular suspicion of

Effect on plant health

Some studies have found causal relationships between glyphosate and increased or decreased disease resistance.[111] Exposure to glyphosate has been shown to change the species composition of endophytic bacteria in plant hosts, which is highly variable.[112]

Glyphosate-based formulations

Glyphosate-based formulations may contain a number of adjuvants, the identities of which may be proprietary.[113] Surfactants are used in herbicide formulations as wetting agents, to maximize coverage and aid penetration of the herbicide(s) through plant leaves. As agricultural spray adjuvants, surfactants may be pre-mixed into commercial formulations or they may be purchased separately and mixed on-site.[114]

Polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) is a surfactant used in the original Roundup formulation and was commonly used in 2015.[115] Different versions of Roundup have included different percentages of POEA. A 1997 US government report said that Roundup is 15% POEA while Roundup Pro is 14.5%.[116] Since POEA is more toxic to fish and amphibians than glyphosate alone, POEA is not allowed in aquatic formulations.[117][116][118] A 2000 review of the ecotoxicological data on Roundup shows at least 58 studies exist on the effects of Roundup on a range of organisms.[104] This review concluded that "...for terrestrial uses of Roundup minimal acute and chronic risk was predicted for potentially exposed non-target organisms".

Human

A 2000 review concluded that "under present and expected conditions of new use, there is no potential for Roundup herbicide to pose a health risk to humans".[120] A 2002 review by the European Union reached the same conclusion.[121]

A 2012 meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (seven cohort studies and fourteen case-control studies) of exposure to glyphosate formulations found no correlation with any kind of cancer.

Aquatic fauna

Glyphosate products for aquatic use generally do not use surfactants, and aquatic formulations do not use POEA due to aquatic organism toxicity.[117][124][125] Due to the presence of POEA, such glyphosate formulations only allowed for terrestrial use are more toxic for amphibians and fish than glyphosate alone.[117][116][118] The half-life of POEA (21–42 days) is longer than that for glyphosate (7–14 days) in aquatic environments.[126] Aquatic organism exposure risk to terrestrial formulations with POEA is limited to drift or temporary water pockets where concentrations would be much lower than label rates.[117]

Some researchers have suggested the toxicity effects of pesticides on amphibians may be different from those of other aquatic fauna because of their lifestyle; amphibians may be more susceptible to the toxic effects of pesticides because they often prefer to breed in shallow,

A 2003 study of various formulations of glyphosate found, "[the] risk assessments based on estimated and measured concentrations of glyphosate that would result from its use for the control of undesirable plants in wetlands and over-water situations showed that the risk to aquatic organisms is negligible or small at application rates less than 4 kg/ha and only slightly greater at application rates of 8 kg/ha."[129]

A 2013 meta-analysis reviewed the available data related to potential impacts of glyphosate-based herbicides on amphibians. According to the authors, the use of glyphosate-based pesticides cannot be considered the major cause of amphibian decline, the bulk of which occurred prior to the widespread use of glyphosate or in pristine tropical areas with minimal glyphosate exposure. The authors recommended further study of species- and development-stage chronic toxicity, of environmental glyphosate levels, and ongoing analysis of data relevant to determining what if any role glyphosate might be playing in worldwide amphibian decline, and suggest including amphibians in standardized test batteries.[130]

Genetic damage

Several studies have not found mutagenic effects,[131] so glyphosate has not been listed in the United States Environmental Protection Agency or the International Agency for Research on Cancer databases.[132] Various other studies suggest glyphosate may be mutagenic.[132] The IARC monograph noted that glyphosate-based formulations can cause DNA strand breaks in various taxa of animals in vitro.[128]

Government and organization positions

This section needs to be updated. (January 2017) |

European Food Safety Authority

A 2013 systematic review by the

In November 2015, EFSA published its conclusion in the Renewal Assessment Report (RAR), stating it was "unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans".EFSA's decision and the BfR report were criticized in an open letter published by 96 scientists in November 2015 saying that the BfR report failed to adhere to accepted scientific principles of open and transparent procedures.[138][139] The BfR report included unpublished data, lacked authorship, omitted references, and did not disclose conflict-of-interest information.[139]

On April 4, 2016, Dr. Vytenis Andriukaitis, European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, wrote an open letter to the Chair of the Board of the Glyphosate Task at Monsanto Europe asking to publish the full studies provided to the EFSA.[140]

In September 2017, The Guardian reported that sections of the Renewal Assessment Report prepared by the BfR and used by Efsa were copy-pasted from a study done by Monsanto. Some sections of copy contained small changes such as using British spelling rather than American forms but others were copied word for word, including most of the peer-reviewed papers that were used in the report. The Guardian reported that a "Monsanto spokesperson said that Efsa allowed renewal reports to be written this way because of the large volume of toxicological studies submitted."[137]

US Environmental Protection Agency

In a 1993 review, the

International Agency for Research on Cancer

In March 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an intergovernmental agency forming part of the World Health Organization of the United Nations, published a summary of their forthcoming monograph on glyphosate, and classified glyphosate as "probably carcinogenic in humans" (category 2A) based on epidemiological studies, animal studies, and in vitro studies. It noted that there was "limited evidence" of carcinogenicity in humans for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[5][8][9][142][143] The IARC classifies substances for their carcinogenic potential, and "a few positive findings can be enough to declare a hazard, even if there are negative studies, as well." Unlike the BfR, it does not conduct a risk assessment, weighing benefits against risk.[144]

The BfR responded that IARC reviewed only a selection of what they had reviewed earlier, and argued that other studies, including a cohort study called Agricultural Health Study, do not support the classification.[145] The IARC report did not include unpublished industry-funded studies, including one completed by the IARC panel leader, Aaron Blair, who stated that agency policy required that he not consider this study.[146] The agency's international protocol dictates that only published studies be used in classifications of carcinogenicity,[147] since national regulatory agencies including the EPA have allowed agrochemical corporations to conduct their own unpublished research, which may be biased in support of their profit motives.[148] Monsanto called the IARC report biased and said it wanted it to be retracted.[149]

A 2017 review done by personnel from EFSA and BfR argued that the differences between the IARC's and EFSA's conclusions regarding glyphosate and cancer were due to differences in their evaluation of the available evidence. The review concluded that "Two complementary exposure assessments ... suggests that actual exposure levels are below" the reference values identified by the EFSA "and do not represent a public concern."[150] In contrast, a 2016 analysis concluded that in the EFSA's Renewal Assessment Report, "almost no weight is given to studies from the published literature and there is an over-reliance on non-publicly available industry-provided studies using a limited set of assays that define the minimum data necessary for the marketing of a pesticide", arguing that the IARC's evaluation of probably carcinogenic to humans "accurately reflects the results of published scientific literature on glyphosate".[151]

In 2017, internal documents from Monsanto were made public by lawyers pursuing litigation against the company.

In October 2017, an article in The Times revealed that Christopher Portier, a scientist advising the IARC in the assessment of glyphosate and strong advocate for its classification as possibly carcinogenic, had received consulting contracts with two law firm associations representing alleged glyphosate cancer victims that included a payment of US$160,000 to Portier.

California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

After the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced, in March 2015, plans to have glyphosate listed as a known carcinogen based on the IARC assessment, Monsanto started a case against OEHHA and its acting director, Lauren Zeise, in 2016,[158] but lost the suit in March 2017.[159]

Glyphosate was listed as "known to the State of California to cause cancer" in 2017.[160] As part of an ongoing case, an injunction was issued prohibiting California from enforcing carcinogenicity labeling requirements for glyphosate stating that arguments by California "[do] not change the fact that the overwhelming majority of agencies that that have examined glyphosate have determined it is not a cancer risk."[161]

European Chemicals Agency

On March 15, 2017 the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) announced recommendations proceeding from a risk assessment of glyphosate performed by ECHA's Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC). Their recommendations maintained the current classification of glyphosate as a substance causing serious eye damage and as a substance toxic to aquatic life. However, the RAC did not find evidence implicating glyphosate to be a carcinogen, a mutagen, as toxic to reproduction, nor as toxic to specific organs.[162]

Effects of use

Emergence of resistant weeds

In the 1990s, when the first genetically modified crops, such as glyphosate-resistant corn, canola, soybean and cotton, were introduced,[163][164] no glyphosate-resistant weeds were known to exist.[165] By 2014, glyphosate-resistant weeds dominated herbicide-resistance research. At that time, 23 glyphosate-resistant species were found in 18 countries.[166] "Resistance evolves after a weed population has been subjected to intense selection pressure in the form of repeated use of a single herbicide."[165][167]

According to Ian Heap, a weed specialist, who completed his PhD on resistance to multiple herbicides in annual ryegrass (

In response to resistant weeds, farmers are hand-weeding, using tractors to turn over soil between crops, and using other herbicides in addition to glyphosate.

Monsanto scientists have found that some resistant weeds have as many as 160 extra copies of a gene called EPSPS, the enzyme glyphosate disrupts.[178]

Palmer amaranth

In 2004, a glyphosate-resistant variation of

Conyza species

Ryegrass

Glyphosate-resistant

Johnson grass

Glyphosate-resistant Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense) is found in glyphosate-resistant soybean cultivation in northern Argentina.[189]

Monarch butterfly

Use of 2-4 D and other herbicides like glyphosate to clear

Legal status

Glyphosate was first approved for use in the 1970s, and as of 2010 was labelled for use in 130 countries.[14]: 2

European Union

In April 2014, the legislature of the Netherlands passed legislation prohibiting sale of glyphosate to individuals for use at home; commercial sales were not affected.[195]

In June 2015, the

A vote on the relicencing of glyphosate in the EU stalled in March 2016. Member states France, Sweden, and the Netherlands objected to the renewal.[198] A vote to reauthorize on a temporary basis failed in June 2016[199] but at the last-minute the license was extended for 18 months until the end of 2017.[200]

On 27 November 2017, a majority of eighteen EU member states voted in favor of permitting the use of herbicide glyphosate for five more years. A qualified majority of sixteen states representing 65% of EU citizens was required.

In December 2018, attempts were made reopen the decision to license the weed-killer. These were condemned by Conservative MEPs, who said the proposal was politically motivated and flew in the face of scientific evidence.[203]

In March of 2019, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ordered the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to release all carcinogenicity and toxicity pesticide industry studies on glyphosate to the general public.[204]

Other countries

In September 2013, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador approved legislation to ban 53 agrochemicals, including glyphosate; the ban on glyphosate was set to begin in 2015.[205][206][207]

In May 2015, the President of Sri Lanka banned the use and import of glyphosate, effective immediately.[208][209] However, in May 2018 the Sri Lankan government decided to re-authorize its use in the plantation sector.[210]

In May 2015, Bermuda blocked importation on all new orders of glyphosate-based herbicides for a temporary suspension awaiting outcomes of research.[211]

In May 2015, Colombia announced that it would stop using glyphosate by October 2015 in the destruction of illegal plantations of coca, the raw ingredient for cocaine. Farmers have complained that the aerial fumigation has destroyed entire fields of coffee and other legal produce.[212]

Legal cases

Lawsuits claiming links to cancer

In June 2018, Dewayne Johnson, a 46-year-old former California school

Advertising controversy

The New York Times reported that in 1996, "Dennis C. Vacco, the Attorney General of New York, ordered the company Monsanto to pull ads that said Roundup was "safer than table salt" and "practically nontoxic" to mammals, birds and fish. The company withdrew the spots, but also said that the phrase in question was permissible under E.P.A. guidelines."[218]

In 2001, French environmental and consumer rights campaigners brought a case against Monsanto for misleading the public about the environmental impact of its herbicide Roundup, on the basis that glyphosate, Roundup's main component, is classed as "dangerous for the environment" and "toxic for aquatic organisms" by the European Union. Monsanto's advertising for Roundup had presented it as biodegradable and as leaving the soil clean after use. In 2007, Monsanto was convicted of false advertising and was fined 15,000 euros. Monsanto's French distributor Scotts France was also fined 15,000 euros. Both defendants were ordered to pay damages of 5,000 euros to the Brittany Water and Rivers Association and 3,000 euros to the Consommation Logement Cadre de vie, one of the two main general consumer associations in France.[219] Monsanto appealed and the court upheld the verdict; Monsanto appealed again to the French Supreme Court, and in 2009 it also upheld the verdict.[220]

In 2016, a lawsuit was filed against

Trade dumping allegations

United States companies have cited trade issues with glyphosate being dumped into the western world market areas by Chinese companies and a formal dispute was filed in 2010.[223][224]

See also

- Monsanto legal cases

- 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- Ammonium sulfamate

- Atrazine

- Environmental impact of pesticides

- Health effects of pesticides

- Integrated pest management

- Regulation of pesticides in the European Union

- Pesticide regulation in the United States

- Séralini affair

References

- ^ ISBN 92-4-157159-4

- ^ Index no. 607-315-00-8 of Annex VI, Part 3, to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. Official Journal of the European Union L353, 31 December 2008, pp. 1–1355 at pp 570, 1100..

- ^ a b United States EPA 2007 Pesticide Market Estimates Agriculture, Home and Garden

- ^ PMID 26823080.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17181.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ a b c d Renewal Assessment Report: Glyphosate. Volume 1. Report and Proposed Decision. December 18, 2013. German Institute for Risk Assessment, page 65. Downloaded from http://dar.efsa.europa.eu/dar-web/provision (registration required)

- ^ PMID 24762670.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ PMID 25801782.

- ^ a b "Press release: IARC Monographs Volume 112: evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. March 20, 2015.

- ^ "European Food Safety Authority - Glyphosate report" (PDF). EFSA. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Glyphosate: EFSA updates toxicological profile | European Food Safety Authority". www.efsa.europa.eu. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Report of the Joint Committee on Pesticide Residues, WHO/FAO, Geneva, 16-May, 2016" (PDF).

- ^ "Glyphosate not classified as a carcinogen by ECHA". ECHA.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-41031-8.)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ "Patent Images". 1.usa.gov.

- PMID 11248008.

- .

- ^ "Glyphosate fact sheet". Pesticides News (33). Pesticide Action Network UK: 28–29. September 1996. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The National Medal of Technology and Innovation Recipients - 1987". The United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ Stong C (May 1990). "People: Monsanto Scientist John E. Franz Wins 1990 Perkin Medal For Applied Chemistry". The Scientist. 4 (10): 28.

- ^ "SCI Perkin Medal". Science History Institute. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ )

- ^ "History of Monsanto's Glyphosate Herbicides" (PDF). Monsanto. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ US application 3799758, John E. Franz, "N-phosphonomethyl-glycine phytotoxicant compositions", published March 26, 1974, assigned to Monsanto Company

- ^ US application 4405531, John E. Franz, "Salts of N-phosphonomethylglycine", published September 20, 1983, assigned to Monsanto Company

- ^ Fernandez, Ivan (May 15, 2002). "The Glyphosate Market: A 'Roundup'". Frost & Sullivan. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- PMID 20080659.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions on the Re-evaluation of Glyphosate". Pest Management Regulatory Agency of Canada. April 28, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ISBN 9781461506034.

- ^ Schuette J. "Environmental Fate of Glyphosate" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation, State of California.

- PMID 22676441.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2006). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 88: Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-tert-Butoxypropan-2-ol. Lyon: IARC/WHO.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (June 2011). Report on Carcinogens (Twelfth ed.). Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Toxicology Program.

- ^ a b FAO (2014). FAO specifications and evaluations for agricultural pesticides: glyphosate (PDF). . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. p. 5.

- .

- PMID 16916934.

- PMID 22554242.

The AAA pathways consist of the shikimate pathway (the prechorismate pathway) and individual postchorismate pathways leading to Trp, Phe, and Tyr.... These pathways are found in bacteria, fungi, plants, and some protists, but are absent in animals. Therefore, AAAs and some of their derivatives (vitamins) are essential nutrients in the human diet, although in animals Tyr can be synthesized from Phe by Phe hydroxylase....The absence of the AAA pathways in animals also makes these pathways attractive targets for antimicrobial agents and herbicides.

- PMID 7396959.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Glyphosate technical fact sheet (revised June 2015)". National Pesticide Information Center. 2010. Archived from the original on 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ a b c "The agronomic benefits of glyphosate in Europe" (PDF). Monsanto Europe SA. February 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-203-02388-4.)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ Purdue University, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Metabolic Plant Physiology Lecture notes, Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, The shikimate pathway – synthesis of chorismate.

- PMID 11171958.

- ^ Glyphosate bound to proteins in the Protein Data Bank

- doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1985.tb00809.x.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ PMID 21668647.

- ^ Knezevic, Stevan Z. (February 2010). "Use of Herbicide-Tolerant Crops as Part of an Integrated Weed Management Program". University of Nebraska Extension Integrated Weed Management Specialist. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - doi:10.1614/IPSM-D-09-00048.1.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ Luijendijk CD, Beltman WH, Smidt RA, van der Pas LJ, Kempenaar C (May 2005). "Measures to reduce glyphosate runoff from hard surfaces" (PDF). Plant Research International B.V. Wageningen.

- PMID 19482331.

- ^ BBC. May 10, 2015. Colombia to ban coca spraying herbicide glyphosate

- ^ "Sugarcane Ripener Recommendations - Glyphosate". Louisiana State University Agricultural Extension Office. September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ MacLean, Amy-Jean. "Desiccant vs. Glyphosate: know your goals - PortageOnline.com". PortageOnline.com. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pre-harvest management options for wheat : Harvest : Small Grains Production : University of Minnesota Extension". www.extension.umn.edu. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ "Harvesting, Grain Drying and Storage - University of Saskatchewan". www.usask.ca. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ Sprague, Christy. "Preharvest herbicide applications are an important part of direct-harvest dry bean production". Michigan State University. Michigan State University Extension, Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Glyphosate formulations and their use for the inhibition of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase".

- ^ "Roundup® for Lawns 4 - Grass Friendly Weed Killer Refill". www.roundup.com.

- PMID 20586458.

- ISBN 978-93-80026-16-9.

- ^ "Company History". Web Site. Monsanto Company.

- ^ "Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crops in the U.S." Economic Research Service. USDA. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ Farm Chemicals International Glyphosate entry in Crop Protection Database

- ^ a b Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development. April 26, 2006. Quick Guide to Glyphosate Products - Frequently Asked Questions

- ^ Hartzler, Bob. "Glyphosate: a Review". ISU Weed Science Online. Iowa State University Extension.

- ^ Tu M, Hurd C, Robison R, Randall JM (November 1, 2001). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ National Pesticide Information Center. Last updated September 2010 Glyphosate General Fact Sheet

- ^ a b c d "Press Release: Research and Markets: Global Glyphosate Market for Genetically Modified and Conventional Crops 2013 - 2019". Reuter. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ monsanto.ca: "VISION SILVICULTURE HERBICIDE", 03-FEB-2011

- ^ China Research & Intelligence, June 5, 2013. Research Report on Global and China Glyphosate Industry, 2013-2017

- ^ Tu M, Randall JM (June 1, 2003). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ Curran WS, McGlamery MD, Liebl RA, Lingenfelter DD (1999). "Adjuvants for Enhancing Herbicide Performance". Penn State Extension.

- ^ VanGessel M. "Glyphosate Formulations". Control Methods Handbook, Chapter 8, Adjuvants: Weekly Crop Update. University of Delaware Cooperative Extension.

- ^ "e-phy". e-phy.agriculture.gouv.fr.

- ^ PMID 18161065.

- PMID 19482331.

- PMID 27035384.

- PMID 25602328.

- ^ a b c d e "Registration Decision Fact Sheet for Glyphosate (EPA-738-F-93-011)" (PDF). R.E.D. FACTS. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 1993.

- ^ .

- PMID 2806176.

- PMID 19447533.

- ^ Ole K, Borggaard OK (2011). "Does phosphate affect soil sorption and degradation of glyphosate? - A review". Trends in Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2 (1): 17–27.

- doi:10.1897/05-152.1.

- ^ Gillam, Carey (November 2016). "Alarming Levels of Glyphosate Found in Popular American Foods". EcoWatch.com. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ European Commission (2017). "EU Pesticides database: Glyphosate". Retrieved August 29, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - PMID 29117584.

- ^ PMID 22835958.

- ^ PMID 15862083.

- ^ Glyphosate: Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment (PDF), Syracuse Environmental Research Associates, Inc.(SERA), retrieved August 20, 2018

- ^ "Committee of Risk Assessment Opinion proposing harmonised classification and labelling at EU level of glyphosate (ISO); N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine".

- ^ .

- PMID 28374158.

- ^ "The BfR has finalised its draft report for the re-evaluation of glyphosate - BfR". Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-6987-1.)

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link - ^ US EPA, OCSPP (December 18, 2017). "EPA Releases Draft Risk Assessments for Glyphosate" (Announcements and Schedules). US EPA. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ^ "Food Controversies—Pesticides and organic foods". Cancer Research UK. 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ PMID 27015139.

- PMID 23286529.

- PMID 25245870.

- ^ Abraham William Wildwood. Glyphosate formulations and their use for inhibition of 5-enolpyrovylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, US Patent 7, 771, 736 B2; 2010

- PMID 11865437.

- PMID 15224916.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-95102-7.

- PMID 21912208.

- ISSN 0038-0717.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ISBN 9780128046814.)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (June 18, 2007). "Draft List of Initial Pesticide Active Ingredients and Pesticide Inerts to be Considered for Screening under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act" (PDF). Federal Register. 72 (116): 33486–503.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (June 29, 2015). "Memorandum: EDSP Weight of Evidence Conclusions on the Tier 1 Screening Assays for the List 1 Chemicals" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2016.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-4020-5797-7.)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - PMID 16903349.

- ^ "Pesticide Registration Manual | Pesticide Registration | US EPA".

- ^ "Adjuvants for Enhancing Herbicide Performance". extension.psu.edu. Penn State Extension. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ "Measuring POEA, a Surfactant Mixture in Herbicide Formulations". U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ a b c Gary L. Diamond and Patrick R. Durkin February 6, 1997, under contract from the United States Department of Agriculture. Effects of Surfactants on the Toxicity of Glyphosate, with Specific Reference to RODEO

- ^ a b c d "SS-AGR-104 Safe Use of Glyphosate-Containing Products in Aquatic and Upland Natural Areas" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ PMID 19500891.

- PMID 1673618.

- PMID 10854122.

- ^ "Review report for the active substance glyphosate" (PDF). Commission working document. European Commission, Health and Protection Directorate-General: Directorate E – Food Safety: plant health, animal health and welfare, international questions: E1 - Plant Health. January 21, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2016.

- PMID 22683395.

- PMID 27267204.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ "Response to "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities"" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company. April 1, 2005.

- ^ "Aquatic Use of Glyphosate Herbicides in Australia" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company. May 1, 2003.

- PMID 26282372.

- )

- ^ a b "IARC monograph on glyphosate" (PDF). IARC. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- PMID 12746143.

- PMID 23637092.

- ^ ToxNet. Glyposate. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ ISBN 978-953-307-803-8, Published: January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Glyphosate: no more poisonous than previously assumed, although a critical view should be taken of certain co-formulants - BfR". www.bfr.bund.de.

- ^ "Glyphosate RAR 01 Volume 1 2013-12-18 San". Renewal Assessment Report. Hungry4Pesticides. December 18, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions on the health assessment of glyphosate" (PDF). Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung. January 15, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - .

- ^ a b Nelson, Arthur. "EU report on weedkiller safety copied text from Monsanto study". The Guardian. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ "Independent scientists warn over Monsanto herbicide". DW. December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Portier, C. J.; et al. (November 27, 2015). "Open letter: Review of the Carcinogenicity of Glyphosate by EFSA and BfR" (PDF). Retrieved December 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Open letter. Subject: Plant protection products - transparency in the context of the decision-making process on glyphosate" (PDF). European Commission. April 4, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Charles, Dan (September 17, 2016). "EPA Weighs In On Glyphosate, Says It Doesn't Cause Cancer". NPR. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2017). IARC Monographs, Volume 112. Glyphosate, in: Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides (PDF). Lyon: IARC/WHO. pp. 321–412.

- ^ Specter, Michael (April 10, 2015). "Roundup and Risk Assessment". New Yorker.

'Probable' means that there was enough evidence to say it is more than possible, but not enough evidence to say it is a carcinogen," Aaron Blair, a lead researcher on the IARC's study, said. Blair, a scientist emeritus at the National Cancer Institute, has studied the effects of pesticides for years. "It means you ought to be a little concerned about" glyphosate, he said.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - )

- ^ "Löst Glyphosat Krebs aus? (announcement 007/2015)" (PDF) (in German). German Institute for Risk Assessment. March 23, 2015.

- ^ Butler, Kiera (June 15, 2017). "A scientist didn't disclose important data—and let everyone believe a popular weedkiller causes cancer". Mother Jones. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Preamble to the IARC Monographs". International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2006.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (November 3, 2015). "EPA used Monsanto's Research to Give Roundup A Pass". The Intercept.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Gillam, Carey (March 24, 2015). "Monsanto seeks retraction for report linking herbicide to cancer". Reuters.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - PMID 28374158.

- PMID 26941213.

- ^ "Glyphosate: IARC (Monsanto shared document)" (PDF). Baum Hedlund Law. February 23, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ^ Hakim, Danny (August 1, 2017). "Monsanto Emails Raise Issue of Influencing Research on Roundup Weed Killer". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- )

- ^ a b c Kabat, Geoffrey. "IARC's Glyphosate-gate Scandal". Forbes. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Kelland, Kate. "Glyphosate: WHO cancer agency edited out". Reuters. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- )

- ^ "Monsanto loses cancer label lawsuit, accused of ghostwriting study". St. Louis Business Journal. March 14, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ "Glyphosate Listed Effective July 7, 2017, as Known to the State of California to Cause Cancer". oehha.ca.gov. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ "Federal judge rules against California's attorney general over..." LA Times. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Glyphosate not classified as a carcinogen by ECHA - All news - ECHA". echa.europa.eu.

- ^ James, Clive (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Roundup Ready System". Monsanto. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Resisting Roundup". The New York Times. May 16, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-94-007-7795-8.

- ^ a b Lori (May 7, 2009). "U of G Researchers Find Suspected Glyphosate-Resistant Weed". Uoguelph.ca. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Heap, Ian Michael (1988). Resistance to herbicides in annual ryegrass (Lolium Rigidum). Adelaide: Department of Agronomy, University of Adelaide.

- ^ King, Carolyn (June 2015). "History of herbicide resistance Herbicide resistance: Then, now, and the years to come". Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Hartzler, Bob (January 29, 2003), "Are Roundup Ready Weeds in Your Future II", Iowa State University (ISU), Weed Science Online, retrieved March 24, 2016

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - JSTOR 4045968.

- ISBN 9781118043547

- ^ "Glyphosate resistance is a reality that should scare some cotton growers into changing the way they do business". Southeastfarmpress.com. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "Weeds Resistant to EPSP synthase inhibitors (G/9) - by species and country". The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017. from link, select Glyphosate from dropdown

- ^ Neuman W, Pollack A (May 4, 2010). "U.S. Farmers Cope With Roundup-Resistant Weeds". New York Times. New York. pp. B1. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- doi:10.1186/2190-4715-24-24.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ Heap I. "Resistance by Active Ingredient (select "glyphosate" from the pulldown menu)". The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ "With BioDirect, Monsanto Hopes RNA Sprays Can Someday Deliver Drought Tolerance and Other Traits to Plants on Demand". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- JSTOR 4539441.

- ^ a b Hampton N. "Cotton versus the monster weed". Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Smith JT (March 2009). "Resistance a growing problem" (PDF). The Farmer Stockman. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- ^ Taylor O (July 16, 2009). "Peanuts: variable insects, variable weather, Roundup resistant Palmer in new state". PeanutFax. AgFax Media. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- .

- JSTOR 4047050.

- PMID 20063320.

- PMID 18161884.

- ^ Jhala, Amit (June 4, 2015). "Post-Emergence Herbicide Options for Glyphosate-Resistant Marestail in Corn and Soybean". CropWatch. Nebraska Extension. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - .

- JSTOR 4539618.

- ^ Kniss, Andrew (February 10, 2014). "Are herbicides responsible for the decline in Monarch butterflies?". Control Freaks. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

The evidence seems clear that the number of milkweed plants through this region has indeed declined. The cause for the milkweed decline, though, is a little less certain.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Plumer, Brad (January 29, 2014). "Monarch butterflies keep disappearing. Here's why". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - doi:10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00196.x.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - doi:10.1016/s0261-2194(00)00024-7.)

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help - ^ "NRDC Sues EPA Over Demise of Monarch Butterfly Population". NBC. 2015.

- ^ Staff, Sustainable Pulse. Apr 4 2014 Dutch Parliament Bans Glyphosate Herbicides for Non-Commercial Use

- ^ "UPDATE 2-French minister asks shops to stop selling Monsanto Roundup weedkiller". Reuters.

- ^ French parliament does not vote for a date to terminate glyphosate: Rejet à l’Assemblée de l’inscription dans la loi de la date de sortie du glyphosate

- ^ Arthur Nelson (March 8, 2016). "Vote on controversial weedkiller's European licence postponed". The Guardian.

- ^ "Recall of Monsanto's Roundup likely as EU refuses limited use of glyphosate". Reuters. June 6, 2016.

- ^ Arthur Nelson (June 29, 2016). "Controversial chemical in Roundup weedkiller escapes immediate ban". The Guardian.

- ^

'EU votes for five more years usage of herbicide glyphosate'. NRC Handelsblad Template:Nl, 28 November 2017.

- NRC Handelsblad, 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Move to re-open Glyphosate case attacked by Conservative MEPs". Conservative Europe. December 6, 2018.

- ^ ‘European Court of Justice orders public release of industry glyphosate studies’ , 7 March 2019.

- ^ Staff, Centralamericadata.com. September 6, 2013 El Salvador: Use of 53 Chemicals Banned

- ^ Staff, Centralamericadata.com. November 27, 2013 El Salvador: Confirmation to Be Given on Ban of Agrochemicals

- ^ Legislative Assembly of El Salvador. November 26, 2013 Analizan observaciones del Ejecutivo al decreto que contiene la prohibición de 53 agroquímicos que dañan la salud English translation by Google

- ^ Staff, Colombo Page. May 22, 2015 Sri Lankan President orders to ban import of glyphosate with immediate effect

- ^ Sarina Locke for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Updated May 27, 2015 Toxicologist critical of 'dodgy science' in glyphosate bans

- ^ "Glyphosate ban lifted for tea, rubber industries: Navin". Daily Mirror. May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Health Minister: importation of roundup weed spray suspended". Bermuda Today. May 11, 2015. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Colombia to ban coca spraying herbicide glyphosate". BBC News. May 10, 2015.

- ^ Sam Levin (July 24, 2018). "Monsanto's 'cancer-causing' weedkiller destroyed my life, dying man tells court". The Guardian.

- ^ Tessa Stuart (August 14, 2018). "Monsanto's EPA-Manipulating Tactics Revealed in $289 Million Case". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Carey Gillam (August 11, 2018). "One man's suffering has exposed Monsanto's secrets to the world". The Guardian. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "Weedkiller glyphosate 'doesn't cause cancer' - Bayer". BBC News. August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ Levin, Sam. "Monsanto ordered to pay $289m as jury rules weedkiller caused man's cancer". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Charry T (May 29, 1997). "Monsanto recruits the horticulturist of the San Diego Zoo to pitch its popular herbicide". Business Day. New York Times.

- ^ "Monsanto fined in France for 'false' herbicide ads". Terradaily.com (January 26, 2007).

- ^ Europe | Monsanto guilty in 'false ad' row. BBC News (October 15, 2009).

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "General Mills drops '100% Natural' on Nature Valley granola bars after lawsuit". USA TODAY. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Hoskins T (April 15, 2010). "Glyphosate maker complains of Chinese dumping". Missouri Farmer Today.

- ^ "In the Matter of: GLYPHOSATE FROM CHINA" (PDF). United States International Trade Commission. April 22, 2010.

External links

- Glyphosate in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- Glyphosate trimesium in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- Glyphosate, isopropylamine salt in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- Glyphosate, potassium salt in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)