User:SomeGuyWhoRandomlyEdits/Early Dynastic IIIb

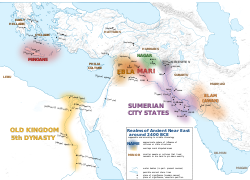

A map detailing the locations of various archaeological sites occupied by the archaeological culture of EDIIIb. | |

| Geographical range | Near East |

|---|---|

| Period | Early Dynastic |

| Dates | c. 2500/2450 – c. 2350/2334 BCE |

| Major sites | |

| Preceded by | Early Dynastic IIIa |

| Followed by | Akkadian Period |

| Defined by | Henri Frankfort |

The Early Dynastic IIIb period (abbreviated EDIIIb period or EDIIIb) is the fourth out of four sub-periods to an

EDIIIb saw an expansion in the use of writing and increasing social inequality. Larger political entities developed in Lower and Upper Mesopotamia; as well as, Southern and Western Iran. The Royal Cemetery at Ur dates back to EDIIIb. The EDIIIb is especially well-known through the Ebla tablets and Barton Cylinder.

The end of EDIIIb is not defined archaeologically but politically. The

Population

Tertius Chandler calculated a range of anywhere from 75 to 200 people inhabiting 1 hectare (110,000 square feet) for the population density of early settlements. Fekri Hassan used a population density standard of 100 inhabitants per hectare. Robert McCormick Adams Jr. estimated an average of 100, 125, or 200 inhabitants/hectare. Colin Renfrew also estimated 200 inhabitants/ha. Hans Jörg Nissen concurred with the density standard of 100—200 inhabitants/ha.

Colin McEvedy wrote that a population density of about 250 inhabitants/ha is a reasonable assumption. Yigael Yadin suggested a high estimate of nearly 600 inhabitants/ha. Paul Bairoch reports that many scholars have used population densities of up to 400 or even 700 per hectare.

Giovanni Pettinato estimated that Ebla occupied 56 hectares.

Estimated settlement sizes (in hectares)

| Settlement | Nissen | Pettinato | Mallowan | Adams | Roux |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu | 50—500 | ||||

| Bad-tibira | 25 | 50—500 | |||

| Larak | 50—500 | ||||

| Sippar | 50—500 | ||||

| Shuruppak | 100 | ||||

| Kish | 84+ | 50—500 | |||

| Uruk | 250 | 400 | 50—500 | ||

| Ur | 50 | 50—500 | |||

| Nippur | 50 | 50—500 | |||

| Girsu | 50—500 | ||||

| Lagash | 50—500 | ||||

| Umma | 400 | 50—500 | |||

| Kesh | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Adab | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Isin | 50—500 | ||||

| Larsa | 50—500 | ||||

| Zabala | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Akshak | 50—500 | ||||

Shekhna

|

100 | ||||

| Nagar | 75—100 | ||||

| Ebla | 56 | ||||

| Anshan |

Estimated settlement populations

| Settlement | Pettinato | Chandler | Whitehouse | Frankfort | McEvedy | Thompson | Modelski |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu | 10,000—20,000 | ||||||

| Bad-tibira | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Larak | 10,000—20,000 | ||||||

| Sippar | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Shuruppak | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—30,000 | 17,000 | ||||

| Kish | 10,000—20,000 | 20,000 | 25,000 | ||||

| Uruk | 50,000 | 50,000 | 30,000—40,000 | 50,000 | |||

| Ur | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 10,000 | ||||

| Adab | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | 13,000 | ||||

| Akshak | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Isin | |||||||

| Larsa | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000 | |||||

| Girsu | 40,000—80,000 | ||||||

| Lagash | 10,000—20,000 | 19,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 30,000—60,000 | 40,000 | ||

| Umma | 10,000—20,000 | 16,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 40,000 | 34,000 | ||

| Eshnunna | 9,000 | ||||||

Tutub

|

12,000 | ||||||

| Nippur | 10,000—20,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | ||||

| Kesh | 10,000 | 11,000 | |||||

| Zabala | 10,000 | ||||||

| Assur | |||||||

| Nineveh | |||||||

| Akkad | |||||||

| Mari | 40,000 | ||||||

| Ebla | ≤40,000 | 30,000 | |||||

Shekhna

|

20,000 | ||||||

| Nagar | 10,000—15,000 | 15,000 | |||||

| Tell Chuera | |||||||

| Anshan | 10,000 | ||||||

| Susa | 10,000—15,000 |

Ethnicities and languages

Ethnic groups

- Sumerian people

- Elamite people

- Semitic people

Languages

- Language isolates

- Proto-Euphratean

- Sumerian

- Emegir variety

- Emesal sociolect

- Elamite

- Semitic

Sumerian people

Most historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled c. 5500 – c. 3300 BC by a West Asian people who spoke Sumerian (a non-Semitic, non-Indo-European, agglutinative, language isolate). Sumerian civilization originated in the southeastern reaches of the Fertile Crescent—a region once widely regarded by the general consensus of mainstream historians to be the only cradle in which the first known complex, non-nomadic, agrarian civilization (that being Sumer) spread out from by influence. The history of Sumer is usually taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid, Uruk, and Jemdet Nasr periods. It appears that the archaeological culture of the Ubaidians' may have been derived from that of the Samarrans'.

Ever since the decipherment of the Sumerian cuneiform script; it has been the subject of much effort to relate it to a wide variety of languages. Proposals for linguistic affinity sometimes have a nationalistic background because it has a peculiar prestige as one of the most ancient written languages. Such proposals enjoy virtually no support among linguists because of their unverifiability. Some

Proto-Euphratean is considered by some to have been the

Other scholars think that the Sumerian language may have originally been that of the hunting and fishing peoples who lived in the

A genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with the inhabitants of the

Elamite people

Semitic people

A Bayesian analysis suggested an origin for all known Semitic languages with a population of ancient Semitic-speaking peoples migrating from the Levant c. 3750 BCE; furthermore, spreading into Mesopotamia and possibly contributing to the collapse of the Uruk period c. 3100 BCE. Kish has been identified as the center of the earliest known East Semitic culture (the Kish civilization). This early East Semitic culture is characterized by linguistic, literary, and orthographic similarities extending across settlements such as Mari, Nagar, Abu Salabikh, and Ebla.

The similarities include the use of a

Throughout the

Languages

Language isolates

Sumerian language

Emegir variety

Emesal sociolect

Proto-Euphratean language

Elamite language

Semitic languages

East Semitic languages

Kishite language

Eblaite language

Mariote dialect

Akkadian language

West Semitic languages

Amorite language

Mathematics, measurement, writing, and timekeeping systems

Mathematics

Cuneiform

Sumerian cuneiform

Akkadian cuneiform

Elamite cuneiform

Literature and other texts

| Publication date(s) | Language(s) | Text(s) | Genre(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian |

|

Creation myth |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian | Kesh temple hymn | Hymn |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Akkadian | Legend of Etana

|

Legend |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian and Eblaite |

Ebla tablets | Gazetteers

|

| c. 2400 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian | Code of Urukagina

|

Legal code

|

Elamite writing systems and scripts

Proto-Elamite script

Linear Elamite

Calendar

Religion

Gods

King of the gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

Primordial gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abzu 𒍪𒀊 abzu |

— | Cosmic ocean | c. 5500 – c. 30 BCE |

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth | Earth

|

c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nammu 𒀭𒇉 dnammu |

— | Motherhood | c. 2500 – c. 1300 BCE |

Divine triad

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

— | Weather | c. 3400 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Water

Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

Seven gods who decree

Four primary gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

— | Weather | c. 3400 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Water

Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ |

— | Fertility | c. 3000 – c. 500 BCE |

Three sky gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

Venus | Love Beauty Justice War |

c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

Moon | Moon | c. 2600 BCE – c. 300 CE |

| Sun | Sun | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

Celestial bodies and gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Sun | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE | |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Water

Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

Venus | Love Beauty Justice War |

c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth | Earth

|

c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

Moon | Moon | c. 2600 BCE – c. 300 CE |

| Nergal 𒀭𒆧𒀕𒀕 dnergalₓ(kiš.abg) |

Mars | Death | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| Marduk 𒀭𒀫𒌓 damar.ud |

Jupiter | Vegetation | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

Other major gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ereshkigal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲 dereš.ki.gal |

— | Chthonic | c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ninurta 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁 dnin.urta |

— | Hunting | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

Minor gods

| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meslamta-ea 𒀭𒈩𒇴𒋫𒌓𒁺 dmes.lam.ta.e₃ |

— | Divine twins | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Pabilsaĝ 𒀭𒉺𒄑𒉋𒊕 dpa.bil₃.saŋ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Bau 𒀭𒁀𒌑 dba.u₂ |

— | Health | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ninegal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒂍𒃲 dnin.e₂.gal |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| Lugal-Urub 𒀭𒈗𒌾 dlugal.urub |

— | — | c. 2500 – c. 1900 BCE |

| Nin-gublaga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒂯 dnin.gublaga |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ištaran 𒀭𒅗𒁲 dištaran |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nintinugga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒁷?𒂵 dnin.tin.ugₓ(ezenₓḫal).ga |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Shara 𒀭𒇋 dšara₂ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 700 BCE |

| Ninlil 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆤 dnin.lil₂ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ninazu 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀀𒍫 dnin.a.zu₅ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Lisin 𒀭𒉈𒋜 dli₉.si₄ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

Posthumously deified rulers of Sumer

| Deity | Dates of worship |

|---|---|

| Lugalbanda 𒀭𒈗𒌉𒁕 dlugal.banda₃da |

c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| c. 2600 – c. 1300 BCE | |

| Gilgamesh 𒀭𒄑𒉋𒂵𒈩 dgilgameš₄ |

c. 2600 – c. 1900 BCE |

Cosmology

Metaphysical realms

| Realm | Placement | Inhabitants | Ruler | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totality 𒆠𒊹 ki.šar₂ |

An 𒀭 an |

Gods 𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾 da.nun.na |

Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki | |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth 𒈠 ma |

Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ | ||

| Ereshkigal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲 dereš.ki.gal | ||||

| Abzu 𒍪𒀊 abzu |

Primeval sea 𒇉 engur |

— | Nammu 𒀭𒇉 dnammu | |

Physical realms

Central realms (Sumer and Akkad)

| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Akkadian + Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | ||

| Kish 𒆧𒆠 kiški + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

|

||

| Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

|

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Mountain of Eanna 𒆳 𒂍𒀭𒈾 kur e₂.an.na.bi + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

|

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Gu-Edin 𒄘𒂔𒈾 gu₂.edin.na + Kalam 𒌦 kalam + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

|

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi |

Northern realms

| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Sea 𒅆𒉏𒈠𒊺 𒀀𒀊𒁀 igi.nim.ma.šea.ab.ba |

|

— | — |

| Shubur 𒋚 šubur |

|

Eastern realms

| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | ||

| Elam 𒉏𒆠 elamki |

|

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Awan 𒀀𒉿𒀭𒆠 a.wa.anki |

|

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Anshan 𒀭𒁺𒀭𒆠 an.ša₄.anki |

|

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Hamazi 𒄩𒈠𒍣𒆠 ḫa.ma.ziki |

|

— | — |

|

Gutian 𒅴𒄖𒋾𒌝 eme gu.ti.um | ||

| Aratta 𒇶𒆠 arattaki |

|

— | — |

|

— | — | |

| Marhasi 𒈥𒄩𒅆𒆠 mar.ḫa.šiki |

|

— | — |

| Meluhha 𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠 me.luḫ.ḫaki |

|

Harappan civilization

|

Harappan script

|

Southern realms

| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

|

— | — | |

| Dilmun 𒉌𒌇 dilmunki |

|

— | — |

| Magan 𒈣𒃶𒆠 ma₂.ganki |

|

— | — |

Western realms

| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martu 𒈥𒌅 mar.tu |

|

Amorites 𒈥𒌅 mar.tu |

Amorite |

| Sutium 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

|

Suteans 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

Sutean 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

Government and administration

Titles

| Sumerian title | Literal translation | European equivalent | Examples | Dates in use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lord of Sumer and king of all the land | King-Emperor | |||

| King of the land | Emperor | |||

| Lugal Kiski 𒈗𒆧𒆠 lugal |

Great king | |||

| Lugal 𒈗 lugal |

Big man | King | ||

| Nin 𒊩𒌆 ereš |

Queen | |||

| Nun 𒉣 nun |

Prince | |||

| Ensi 𒉺𒋼𒋛 ensi₂ |

Lord of the plowland | Governor | ||

| En 𒂗 en |

Lord | Lord | ||

| Lú 𒇽 lu₂ |

Man | |||

| Slave |

Law and order

Anthropological evidence suggests that most societies before Sumer, along with most contemporary civilizations, were relatively

Sumerian myths suggested a prohibition against premarital sex. Marriages were often arranged by the parents of the bride and groom; engagements were usually completed through the approval of contracts recorded on clay tablets. These marriages became legal as soon as the groom delivered a bridal gift to his bride's father. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that premarital sex was a common, but surreptitious, occurrence. Prostitution existed but it is not clear if sacred prostitution did.

Code of Urukagina

Despite these apparent attempts to curb the excesses of the elite class, it seems elite or royal women enjoyed even greater influence and prestige in Urukagina's reign than previously. Urukagina greatly expanded the royal "Household of Women" from about 50 persons to about 1,500 persons, then renamed it to "Household of Goddess Bau", gave it ownership of vast amounts of land confiscated from the former priesthood, and placed it under the supervision of Urukagina's wife (Shasha, or Shagshag). During the second year of Urukagina's reign, his wife presided over the lavish funeral of his predecessor's queen (Baranamtarra, who had been an important personage in her own right).

In addition to such changes, two of Urukagina's other surviving decrees have attracted controversy in recent decades:

- Urukagina seems to have abolished the former custom of polyandry in his country, on pain of the woman taking multiple husbands being stoned with rocks upon which her crime was written.

- In a statute where it was written: "If a woman says [text illegible...] to a man, her mouth is crushed with burnt bricks."

No comparable

Reform Document

The following extracts are taken from the Reform Document:

- "From the border territory of Ningirsu to the sea, no person shall serve as officers."

- "For a corpse being brought to the grave, his beer shall be 3 jugs and his bread 80 loaves. 1 bed and 1 lead goat shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the person(s) take away."

- "When to the reeds of Enki a person has been brought, his beer will be 4 jugs, and his bread 420 loaves. 1 barig of barley shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the persons of... take away. 1 woman’s headband, and 1 sila of princely fragrance shall the eresh-dingir priestess take away. 420 loaves of bread that have sat are the bread duty, 40 loaves of hot bread are for eating, and 10 loaves of hot bread are the bread of the table. 5 loaves of bread are for the persons of the levy, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Girsu. 490 loaves of bread, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Lagash. 406 of bread, 2 mud vessels, and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the other lamentation singers. 250 loaves of bread and 1 mud vessel of beer are for the old wailing women. 180 loaves of bread and one mud vessel of beer are for the men of Nigin."

- "The blind one who stands in..., his bread for eating is 1 loaf, 5 loaves of bread are his at midnight, 1 loaf is his bread at midday, and 6 loaves are his bread in the evening."

- "60 loaves of bread, 1 mud vessel of beer, and 3 ban of barley are for the person who is to perform as the sagbur priest."

Economy, commerce, and trade

The Sumerian people used

Trade and commerce

Imports

Imports to Ur reflected the cultural and trade connections of the Sumerian city. During the EDIII, Ur was importing elite goods from geographically distant places. These objects included:

The combination of these means of transportation allowed access to a vast trading network connecting distant places. Most of the gold known from archaeological contexts during the EDIII is concentrated at the royal cemetery of Ur. Textual evidence indicates that gold was reserved for prestige and religious functions. It was gathered in royal treasuries and temples, and used for the adornment of the elites as well as for the elites' funerary offerings (such as at the graves of the Royal Cemetery of Ur). Gold was used for personal ornaments, weapons, tools, sheet-metal

Silver was mainly used for uncoined currency; but, it was also used for objects (which is the state in which silver is found at the royal cemetery of Ur). Silver was used for objects including: belts, vessels, hair ornaments, pins, weapons, cockle shells, and sculptures. There are very few literary references to sources for silver. It is also difficult to identify the actual origin of the silver and the mines from those areas in which the majority of trade occurred. Because silver was used as currency it is even more difficult to pinpoint an area of origination due to its vast circulation.

Lapis lazuli is the best-known and well-documented gemstone at Ur (and Mesopotamia in general). In the royal cemetery of Ur, lapis lazuli was discovered to have been used for: jewelry, plaques, gaming boards, lyres, ostrich-egg vessels, and also used for parts of a larger sculptural group referred to as the Ram in a Thicket. Some of the larger objects included a spouted cup, dagger-hilt, and whetstone. Because of its prestige and value, lapiz lazuli played a special role in cult practices and the term lapis-like is a commonly-occurring metaphor for unusual wealth and as an attribute used to described both deities and heroes. It has been commonly found associated alongside gold.

During the EDIII, chlorite stone artifacts were very popular (and thus traded very widely). Chlorite stone artifacts included disc beads, ornaments, and stone vases. These carved dark stone vessels have been found in ancient

-

A bowl made out of gold (dated to c. 2600 – c. 2300 BCE)

-

A pouring vessel made out of a shell imported from the Gulf of Oman (dated to c. 2700 – c. 2500 BCE)

Exports

Natural resources

Culture

Daily life

Arts and crafts

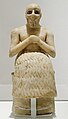

Sculpting

Metalworking and goldsmithing

Cylinder seals

Inlays

Fashion

Jewelry

-

Gold and lapis lazuli choker

-

Gold necklace

-

Gold pendant

-

Gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian garter

-

Goldfinger rings

-

Lapis lazuli fish amulet

-

Lapis lazuli and carnelian cuff

Games

Music

Architecture

Dwellings

Mudbrick houses

Mesopotamian

The larger, more complex houses had square centre rooms or long-roofed central hallways with other, smaller rooms attached to the central ones; but, a great variation in the size and materials used to build the houses suggest they were built by the inhabitants themselves. These houses could be tripartite, round, or rectangular. Such houses had

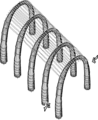

Reed huts

The smaller, simpler houses may not have coincided with the poorest people; in fact, it could be that the poorest people built houses out of perishable materials such as from reeds on the outskirts of settlements; however, there is very little direct evidence for this. Mudhifs (or reed huts) could be constructed out of bundles of reeds which would be tied to form parabolic arches (which make up the buildings' spines). These arches were strengthened by the pre-stressing of the columns, as they were initially inserted into the soil at opposing angles. Long cross beams of smaller, bundled reeds were laid across the arches and tied. The front and back walls were attached to two large vertical bundled reed columns and also made from woven mats.

Public buildings

Temples and ziggurats

The precursors of

The urban nucleus of Eridu was the Eabzu ziggurat temple surrounded by the Mesopotamian Marshes near the ancient Persian gulf coastline. Four separate excavations at the site have demonstrated the existence of a shrine dated to the Ubaid period. The temple was expanded 18 times from c. 5300 – c. 300 BCE. On this basis it has been hypothesized that the tutelary deity of the temple was originally Abzu (later re-dedicated to Enki). Four separate excavations at the site of Eridu have demonstrated the existence of a shrine (with a surface area of 0.9 m2 (9.7 sq ft) c. 5300 BCE) located at the edge of a swamp that was expanded up to a surface area of 286 m2 (3,080 sq ft) by c. 3800 BCE.

Religious precincts

Two such religious precincts (or districts) were named after two gods of Sumerian religion: Anu (the Anu or Kullaba district) and Inanna (the Eanna district). The two districts merged to form a city known to the Sumerians as Uruk c. 5000 – c. 4000 BCE. It was at Uruk that the Sumerians began construction of the Anu ziggurat c. 4000 – c. 3500 BCE. The ziggurat reached to be 13 metres (43 feet) high c. 4000 – c. 3500 BCE and remained the world's tallest freestanding structure for over a thousand years until surpassed by the pyramid of Djoser. The design of Egyptian pyramids (especially the stepped designs of the oldest pyramids) may have been an evolution from the ziggurats built in Mesopotamia.

Tells

In order to harden mudbricks; they were baked out in the Sun to dry. These types of bricks are much less durable than oven-baked ones; so, buildings eventually deteriorated. They were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This planned structural life cycle gradually raised the level of cities, so that they came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resulting mounds are known as tells, and are found throughout the Near East.

Sites

List

| Ancient name | Modern name | Temple | Tutelary deity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu 𒉣𒆠 eridugki |

Tell Abu Shahrain | Eabzu 𒂍𒍪𒀊 e₂.abzu |

Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

| Tell al-Lahm | Nergal 𒀭𒆧𒀕𒀕 dnergalₓ(kiš.abg) | ||

| Ur | Tell al-Muqayyar | 𒂍𒆧𒉡𒅅 e₂.kiš.nu.ŋal₂ |

Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

| Kesh 𒋙𒀭𒄲𒆠 keš₃ki |

Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ | ||

| Larsa 𒌓𒀕𒆠 larsamki |

Tell as-Senkereh | Ebabbar 𒂍𒌓𒌓 e₂.babbar₂ |

|

| Uruk | Tell al-Warka | Eanna 𒂍𒀭𒈾 e₂.an.na |

|

| Bad-tibira 𒂦𒁾𒉄𒆠 bad₃.tibiraki |

Emush 𒂍𒈹 e₂.muš₃ |

Ama-ušumgal-ana 𒀭𒂼𒃲𒁔 dama.ušumgal | |

| Lagash 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 lagaški |

Tell al-Hiba | ||

| Girsu 𒄈𒋢𒆠 ŋir₂.suki |

Tell Telloh | ||

| Umma | Tell Jokha | Emah 𒂍𒈤 e₂.maḫ |

Shara |

| Zabala | Tell Ibzeikh | Ezi-kalam-ma | |

| Nippur | Tell Nuffar | Ekur 𒂍𒆳 e₂.kur |

Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

| Shuruppak | Tell Fara | E-dimgalanna | Sud |

| Marad 𒀫𒁕𒆠 marad.daki |

Tell Wannat es-Sadum | ||

| Adab 𒌓𒉣𒆠 adabki |

Tell Bismaya | Eshar 𒂍𒊬 e₂.šar |

Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

| Isin 𒅔𒆠 isin₂ki |

Ishan al-Bahriyat | E-ni-dub-bi | Nintinugga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒁷?𒂵 dnin.tin.ugₓ(ezenₓḫal).ga |

| Kisurra 𒆠𒋩𒊏 kisur.ra |

Tell Abu Hatab | ||

| Eresh 𒉀𒆠 ereš₂ki |

Tell Abu Salabikh | Baal | |

| Dilbat 𒌓𒉣𒆠 dil.batki |

Tell ed-Duleim | E-ibe-anu | Urash

|

| Larak 𒆷𒊏𒀝𒆠 la.ra.agki |

Pabilsaĝ | ||

| Kish 𒆧𒆠 kiški |

Tell Uheimir | E-dub | Zababa |

| Kutha | Tell Ibrahim | E-meslam | |

| Urum | E-ab-lu-a | Suen | |

| Sippar | Tell Abu Habbah | E-babbar | Utu

|

| Sippar-Amnanum | Tell ed-Der | ||

| Der 𒂦𒆠 durumki |

al-Badra | E-dim-gal-kalama | Ištaran |

| Akshak 𒌔𒆠 akšakki |

|||

| Akkad 𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠 a.ga.de₃ki |

E-an-da-di-a | ||

Tutub |

Tell Khafajah | Temple of Nintu | Nintu |

| Eshnunna 𒀊𒉣𒈾𒆠 eš₃.nun.naki |

Tell Asmar | Esikil 𒂍𒂖 e₂.sikil |

Tishpak and Ninazu |

Map

Technology

Examples of Sumerian technology include: the wheel, cuneiform script,

- clinker-built sailboats stitched together with hair, featuring bitumen waterproofing

- skin boats constructed from animal skins and reeds

- wooden-oared ships, sometimes pulled upstream by people and animals walking along the nearby banks

Agriculture, domestication, and hunting

Agriculture

Mesopotamian houses had enclosed gardens with trees and other plants;

Animal husbandry

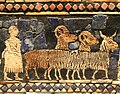

The

-

A photographic image detailing the "peace" panels on the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a man leading a ram on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a man and three goats on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of two men leading a bovid on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of two men leading an equid on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of men carrying offerings on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a feast on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

Tools and utensils

Knives, drills, wedges and an instrument that looks like a saw were all known.

-

Two adzeheads made out of a copper alloy discovered in the Royal Cemetery at Ur.

-

Goldchisels

-

Gold tweezers

-

Gold cup and bowl

-

Gold shell-shaped cosmetic container

-

goblet

-

Gold hairpin

-

Gold chain

War and peace

Military systems

Weapons and armor

-

Copper alloy axe

-

Copper alloy crescent-shaped axehead

-

Gold spearhead and copper alloy bow ends

-

Copper alloy dagger and silver spearhead

-

Copper alloy lanceheads

-

Copper alloy harpoons

-

Gold spearhead

Military history of Mesopotamia

Warfare in Lower Mesopotamia

Lagash-Umma border conflict

The first war in Sumerian

The armies of the city-states could each have up to 3,600—5,400 soldiers. The organization of their armies was based on multiples of 6 (60, 120, 600, etc.) These large armies would consist of many

To support the main army there would be four-wheeled

The

-

Stele of Vultures

-

Stele of Vultures

-

Stele of Vultures

-

Stele of Vultures

-

Stele of Vultures

Warfare in Upper Mesopotamia

Mari-Ebla war

History of Mesopotamia (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BCE)

Sumerian civilization (c. 5500 – c. 1792 BCE)

| c. 5500 BCE–c. 1792 BCE | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Civilization | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | No single/fixed capital

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era |

| ||||||||||||||||||

• Developed | c. 5500 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||

• Transitioned | c. 1792 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Ur (c. 3800 – c. 500 BCE)

Ur I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2400 BCE)

The

Ur-Pabilsag is the earliest known ruler of Ur said to have held the Sumerian title for king. He was preceded by his father A-Imdugud (who ruled over Ur with the Sumerian title for governor) and succeeded by his son Meskalamdug (who r. c. 2600 – c. 2550 BCE as a king). Mesannepada (r. c. 2500 BCE) is the first king of Ur listed on the SKL. Two other rulers earlier than Mesannepada are known from other sources, namely Puabi (probably r. c. 2550 BCE with the Sumerian title for queen) and Akalamdug (r. c. 2600 – c. 2550, c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE as king). It would seem that both Akalamdug and Mesannepada may have been sons of Meskalamdug, according to an inscription found on a bead in Mari and Meskalamdug may have been the true founder of the first dynasty.

Mesilim (r. c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE) may have enjoyed suzerainty over both Ur and Adab. He is also mentioned in some of the earliest monuments as arbitrating a border dispute between Lagash and Umma. Mesilim's placement before, during, or after the reign of Mesannepada in Ur is uncertain, owing to the lack of other synchronous names in the inscriptions, and his absence from the SKL. Some have suggested that Mesilim and Mesannepada were in fact one and the same; however, others have disputed this theory. Both Mesilim and Mesannepada also seem to have subjected Kish, thereafter assuming the title king of Kish for themselves. The title king of Kish would be used by many kings of the preeminent dynasties for some time afterward.

Mesannepada (r. c. 2500 BCE) is the first king of Ur listed on the SKL. Mesannepada may have been a son of king Meskalamdug, according to an inscription found on a bead in Mari, and Meskalamdug may have been the true founder of the first dynasty. Some have suggested that Mesilim and Mesannepada were in fact one and the same; however, others have disputed this theory. Both Mesilim and Mesannepada also seem to have subjected Kish, thereafter assuming the title king of Kish for themselves. The title king of Kish would be used by many kings of the preeminent dynasties for some time afterward.

The

The Ur I dynasty had enormous wealth as shown by the lavishness of its tombs. This was probably due to the fact that Ur acted as the main harbour for trade with India, which put her in a strategic position to import and trade vast quantities of gold, carnelian or lapis lazuli. In comparison, the burials of the kings of Kish were much less lavish. High-prowed Summerian ships may have traveled as far as Meluhha, thought to be the Indus region, for trade.

Ur II dynasty (c. 2400 – c. 2340 BCE)

The rulers from the second dynasty of Ur may have r. c. 2400 – c. 2340 BCE. It was preceded by the second dynasty of Uruk on the SKL. Only two, three, or four rulers are mentioned: Nanni, Meskiagnun (son of Nanni), and two unnamed rulers with unknown fathers. Likewise on the SKL: the second dynasty of Ur was succeeded by a dynasty from Adab. Little more is otherwise known about this dynasty; in fact, the once supposed second dynasty of Ur may have never existed.

Uruk (c. 5000 BCE – c. 700 CE)

Uruk II dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2355 BCE)

Lugalkinishedudu may have retained some of the power inherited by his predecessors—which included rule over Uruk, Ur, and assumed the title king of Kish. The oldest known written mention of a peace treaty between two kings is on a clay nail found in Girsu, commemorating the alliance between Lugalkinishedudu and Entemena of Lagash.

Uruk III dynasty (c. 2355 – c. 2330 BCE)

Urukagina was overthrown and his city Lagash captured by

Lagash (c. 2600 – c. 2030 BCE)

Lagash I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2342 BCE)

The rulers of this dynasty are believed to have r. c. 2570 – c. 2350, c. 2494 – c. 2342 BCE. Although the first dynasty of Lagash has become well-attested through several important monuments, many archaeological finds, and well-known based off of mentions on inscriptions contemporaneous with other dynasties from the EDIII period; it was not inscribed onto the SKL. One fragmentary supplement names the rulers of Lagash. The first dynasty of Lagash preceded the dynasty of Akkad in a time in which Lagash exercised considerable influence in the region.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of

Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, Enannatum I (r. c. 2424 – c. 2421, c. 2425 – c. 2405 BCE). During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Illi, who also attacked Lagash.

His son and successor Entemena (r. c. 2420 – c. 2393, c. 2405 – c. 2375 BCE) restored the prestige of Lagash. Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre. A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the eagle crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained. A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur. After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt rulers is attested for Lagash: Enannatum II, Enentarzi, Enlitarzi, and Lugalanda who altogether r. c. 2392 – c. 2361, c. 2375 – c. 2352 BCE. The last of these, Urukagina (r. c. 2361 – c. 2350, c. 2352 – c. 2342 BCE), was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms (as part of the Code of Urukagina), and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

Later,

Umma (c. 2600 – c. 2022 BCE)

Umma I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2355 BCE)

Umma was an ancient city in Sumer best known for its century-long border war against Lagash over the Gu-Edin plain between Umma's earliest known ruler Pabilgagaltuku (r. c. 2600 – c. 2520, c. 2535 – c. 2455 BCE) and Lagash's Ur-Nanshe. Pabilgagaltuku was subsequently defeated, seized, vanquished by Ur-Nanshe and succeeded by a governor Ush (r. c. 2520 – c. 2441, c. 2455 – c. 2445 BC). Ush is mentioned on the Cone of Entemana as having violated the frontier with Lagash—a frontier which had been solemly established by king Mesilim of Kish. It is thought that Ush was severely defeated by Eannatum. The Stele of the Vultures suggests that Ush was killed in a rebellion in his capital city of Umma after the loss of 3,600 soldiers on the field.

Adab (c. 2600 – c. 1760 BCE)

Adab dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 1760 BCE)

Elamite civilization (c. 3200 BCE – c. 224 CE)

Awan (c. 2600 – c. 2100 BCE)

Awan dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2100 BCE)

According to the SKL: a

The dynasty of Awan was the first from Elam of which anything is known today. The dynasty corresponds to the Old Elamite period (c. 2700 – c. 1600 BCE).

As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain. Little more of these rulers' reigns is known, but the Elamites were likely major rivals of neighboring Sumer from remotest antiquity; they were said to have been defeated by Enmebaragesi, who is the earliest archaeologically attested Sumerian king, as well as by a later monarch, Enannatum I. It is also known that the Elamites carried out incursions into Mesopotamia, where they ran up against the most powerful city-states of this period, Kish and Lagash. One such incident is recorded in a tablet addressed to Enetarzi, a minor ruler or governor of Lagash, testifying that a party of 600 Elamites had been intercepted and defeated while attempting to abscond from the port with plunder.

Luh-ishan (r. c. 2350 – c. 2331, c. 2350 – c. 2320 BCE) is the eighth ruler on the Susanian dynastic list, while his father's name "Hishiprashini" is a variant of that of the ninth listed ruler, Hishepratep—indicating either a different individual or (if the same)—that the order of rulers on the Susanian dynastic list has been jumbled. Events become a little clearer at the time of the

After the death of Emahsini, Elam became a vassal state ruled by several Akkadian governors. Among these governors were: Eshpum, Epirmupi, and Ili-ishmani. The last two ruled with both the Sumerian title for governor and the Akkadian title for military governor. They r. c. 2300 – c. 2153, c. 2270 – c. 2154 BCE.

Hamazi (c. 2600 – c. 2010 BCE)

Hamazi dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2010 BCE)

A copy of a diplomatic message sent from Irkab-Damu (r. c. 2340 BCE as the malikum of Ebla) to Zizi (r. c. 2450 BCE as a ruler of Hamazi) was found among the Ebla tablets. According to the SKL, king Hadanish of Hamazi (r. c. 2450 – c. 2430 BCE) held the hegemony over Sumer after defeating Kish; however, he was in turn defeated by Enshakushanna of Uruk.

Hamazi was one of the provinces under the reign of

Kish civilization (c. 3100 – c. 2350 BCE)

Kish (c. 3750 BCE – c. 1200 CE)

Kish II dynasty (c. 2585 – c. 2430 BCE)

Two rulers (neither appear on the SKL) are known to have ruled from Kish in between the first and second dynasties: Uhub (r. c. 2570 – c. 2550 BCE) and Mesilim (r. c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE). The SKL names another eight kings for this dynasty: Susuda, Dadasig, Mamagal, Kalbum, Tuge, Mennuna, Enbi-Ishtar, and Lugalngu. Next to nothing is known about the aforementioned eight.

Kish III dynasty (c. 2430 – c. 2360 BCE)

The third dynasty of Kish is unique in that it is represented by a woman named Kubaba (r. c. 2450 – c. 2365, c. 2430 – c. 2350 BCE). The SKL adds that she had been a tavern-keeper before overthrowing the hegemony of Mari and becoming monarch. According to the Weidner Chronicle: the god Marduk handed over the kingship to Kubaba of Kish during the reign of Puzur-Nirah of Akshak; although, according to the SKL: the Akshak dynasty succeeded the third of Kish. Although its military and economic power was diminished, Kish retained a strong political and symbolic significance. Just as with Nippur to the south, control of Kish was a prime element in legitimizing dominance over the north of Mesopotamia (Assyria and/or Subartu).

Kubaba's dynasty is sometimes said to include her son

Kish IV dynasty (c. 2360 – c. 2254 BCE)

The kings of the fourth dynasty of Kish are believed to have r. c. 2360 – c. 2254, c. 2340 – c. 2254 BCE. Some versions of the SKL lists 6, 7, or 8 kings (including the son and grandson of Kubaba from the third dynasty). Beside the aforementioned two related to the third dynasty, there is: Zimudar, Usiwater, Eshtar-muti, Ishme-Shamash, Shu-ilishu, Nanniya. Zimudar and his successors seem to have been vassals for Sargon of Akkad, and there is no evidence that they ever exercised hegemony in Sumer.

Mari (c. 2900 – c. 300 BCE)

Mari I dynasty (c. 2900 – c. 2550 BCE)

Mari did not start off as a small settlement that later grew; but, more of a

Mari II dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2330 BCE)

The names of the kings from the first Mariote kingdom were damaged on earlier copies of the SKL, and those kings were correlated with historical kings that belonged to the second kingdom. However, an undamaged copy of the SKL that dates to the old Babylonian period was discovered in Shubat-Enlil, and the names bear no resemblance to any of the historically-attested rulers of the second Mariote kingdom, indicating that the compilers of the SKL had an older (and probably legendary) dynasty in mind that predates the second kingdom

The rulers of the second Mariote kingdom held the Sumerian title for king, and many are attested in the city, the most important source being a letter written by king Enna-Dagan c. 2350 BCE to Irkab-Damu of Ebla. The chronological order of the kings from the second kingdom era is highly uncertain; nevertheless, it is assumed that the letter of Enna-Dagan lists them in a chronological order. Many of the kings were attested through their own votive objects discovered in the city, and the dates are highly speculative. The kings of the second Mariote kingdom may have r. c. 2550 – c. 2290, c. 2450 – c. 2260 BCE.

The earliest attested king in the letter of Enna-Dagan is Ansud, who is mentioned as attacking Ebla, the traditional rival of Mari with whom it had a century-long war, and conquering many of Ebla's cities, including the land of Belan. The next king mentioned in the letter is Saʿumu (r. c. 2416 – c. 2400 BCE), who conquered the lands of Ra'ak and Nirum. King Kun-Damu (r. c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Ebla defeated Mari in the middle of the 25th century BCE. The war continued with Ishtup-Ishar (r. c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Mari's conquest of Emar at a time of Eblaite weakness in the mid-24th century BCE. King Igrish-Halam (r. c. 2360 – c. 2340 BCE) of Ebla had to pay tribute to Iblul-Il (r. c. 2425 – c. 2400, c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Mari, who is mentioned in the letter, conquering many of Ebla's cities and campaigning in the Burman region.

Enna-Dagan also received tribute; his reign fell entirely within the reign of Irkab-Damu of Ebla, who managed to defeat Mari and end the tribute. Mari defeated Ebla's ally Nagar in year seven of the Eblaite vizier Ibrium's term, causing the blockage of trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia. The war reached a climax when the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish made an alliance with Nagar and Kish to defeat Mari in a battle near Terqa. Ebla itself suffered its first destruction a few years after Terqa c. 2300 BCE, during the reign of the Mariote king Hidar. According to Alfonso Archi, Hidar was succeeded by Ishqi-Mari whose royal seal was discovered. It depicts battle scenes, causing Archi to suggest that he was responsible for the destruction of Ebla while still a general.

Akshak (c. 2600 – c. 2330 BCE)

Akshak dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2330 BCE)

Akshak achieved independence with a line of five or six kings extending from Unzi, Undalulu, Urur to Puzur-Nirah, Ishu-Il, and Shu-Suen (son of Ishu-Il). These kings of Akshak r. c. 2459 – c. 2360 BCE before being defeated by the kings in the fourth dynasty of Kish. One ruler preceding Unzi by the name of Zuzu (r. c. 2470 BCE) may have been smited by Eannatum of Lagash.

Ebla (c. 3500 BCE – c. 600 CE)

Ebla I dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2290 BCE)

Assur (c. 2600 BCE – c. 1400 CE)

Assur I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2025 BCE)

Timeline

Legend:

- Red denotes rulers of Ur

- Orange denotes rulers of Awan

- Gold denotes rulers of Kish

- Yellow denotes rulers of Hamazi

- Lime denotes rulers of Uruk

- Fern denotes rulers of Lagash

- Green denotes rulers of Umma

- Teal denotes rulers of Adab

- Blue denotes rulers of Mari

- Purple denotes rulers of Akshak

- Silver denotes rulers of Ebla

- Gray denotes rulers of Nagar

- Black denotes rulers of Assur