Hermann Staudinger

Hermann Staudinger | |

|---|---|

ETH Zürich University of Freiburg | |

| Thesis | Anlagerung des Malonesters an ungesättigte Verbindungen (1903) |

| Doctoral advisor | Daniel Vorländer |

| Doctoral students | Werner Kern Tadeusz Reichstein Leopold Ružička Rudolf Signer |

Hermann Staudinger (German pronunciation:

He is also known for his discovery of

Early work

Staudinger was born in 1881 in

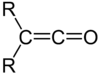

It was here that he discovered the ketenes, a family of molecules characterized by the general form depicted in Figure 1.[3] Ketenes would prove a synthetically important intermediate for the production of yet-to-be-discovered antibiotics such as penicillin and amoxicillin.[4]

In 1907, Staudinger began an assistant professorship at the

The Staudinger reaction

In 1912, Staudinger took on a new position at the

World War I

While in autumn 1914 German professors joined the widespread public support of the war, Staudinger refused to sign Manifesto of the Ninety-Three and joined the few exceptions like Max Born, Otto Buek and Albert Einstein in condemning it. In 1917 he authored an essay predicting the defeat of Germany due to industrial superiority of the Entente and called for a peaceful settlement as soon as possible, and after the entrance of the US he repeated the call in a long letter to the German military leadership.[9] Fritz Haber attacked him for his essay, accusing him of harming Germany, and Staudinger in turn criticized Haber for his role in the German chemical weapons program.

Polymer chemistry

While at Karlsruhe and later, Zurich, Staudinger began research in the chemistry of

At the time, leading organic chemists such as

In 1926, he was appointed lecturer of chemistry at the

Private life

He married in 1906 to Dora Förster and they remained together until their divorce in 1926. They had four children including Eva Lezzi (1907-1993) and Klar (Klara) Kaufmann who were active in resisting the rise of fascism. Dora married again and became a leading peace activist.[2]

In 1927, he married the Latvian botanist, Magda Voita (also shown as; German: Magda Woit), who was a collaborator with him until his death and whose contributions he acknowledged in his Nobel Prize acceptance.[13]

In 1935 Staudinger became a Patron Member of the SS.[14][15][16]

Legacy

Staudinger's groundbreaking elucidation of the nature of the high-molecular weight compounds he termed Makromoleküle paved the way for the birth of the field of polymer chemistry.

See also

- Beta-lactam

- Carbene

- Hypervalent molecule

- Polyoxymethylene

- Pyrethrin

- Triphenylphosphine phenylimide

- Heidegger and Nazism: denounced or demoted non-Nazis

Notes

- ^ "Hermann Staudinger - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. 1953. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Staudinger, Dora". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in German). Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-319-55621-5.

- ^ PMID 14983438.

- .

- .

- PMID 15199557.

- ^ "Life and work of Hermann Staudinger".

- .

- S2CID 46017893.

- ^ Biography on Nobel prize website

- ^ Ogilvie & Harvey 2000, p. 1223.

- ^ Bernd Martin: Die Entlassung der jüdischen Lehrkräfte an der Freiburger Universität und die Bemühungen um ihre Wiedereingliederung nach 1945. In: Freiburger Universitätsblätter. H. 129, September 1995, pp. 7–46.

- ^ Guido Deußing, Markus Weber, Das Leben des Hermann Staudinger, k-online, 2012, Teil 3.

- ^ Uta Deichmann, Flüchten, Mitmachen, Vergessen. Chemiker und Biochemiker in der NS-Zeit. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH 2001.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1953 (accessed Mar 2006).

- ^ "Hermann Staudinger and the Foundation of Polymer Science". International Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

References

- PMID 14983439.

- Heinrich Hopff (1969). "Hermann Staudinger 1881–1965". .

- ISBN 978-0-415-92040-7.

External links

- Works by or about Hermann Staudinger at Internet Archive

- Hermann Staudinger on Nobelprize.org

- Staudinger's Nobel Lecture Macromolecular Chemistry