Lemur

| Lemurs Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A sample of lemur diversity; 8 of 15 biological genera are depicted (from top, left to right): Lemur, Propithecus, Daubentonia, †Archaeoindris, Microcebus, Lepilemur, Eulemur, Varecia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Infraorder: | Lemuriformes |

| Superfamily: | Lemuroidea Gray 1821 |

| Families | |

| |

| Diversity | |

About 100 living species

| |

| |

| Range of all lemur species[3] | |

Lemurs (

Lemurs share resemblance with other primates, but evolved independently from monkeys and apes. Due to Madagascar's highly seasonal climate, lemur evolution has produced a level of species diversity rivaling that of any other primate group.

Living lemurs range in weight from the 30-gram (1.1 oz)

Lemurs are generally the most social of the strepsirrhine primates, living in groups known as troops. They communicate more with scents and vocalizations than with visual signals. Lemurs have a relatively low

Lemur research during the 18th and 19th centuries focused on taxonomy and specimen collection. Modern studies of lemur ecology and behavior did not begin in earnest until the 1950s and 1960s. Initially hindered by political issues on Madagascar during the mid-1970s, field studies resumed in the 1980s. Lemurs are important for research because their mix of ancestral characteristics and traits shared with anthropoid primates can yield insights on primate and

Many lemur species remain endangered due to habitat loss and hunting. Although local traditions, such as fady, generally help protect lemurs and their forests, illegal logging, economic privation and political instability conspire to thwart conservation efforts. Because of these threats and their declining numbers, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) considers lemurs to be the world's most endangered mammals, noting that as of 2013[update] up to 90% of all lemur species confront the threat of extinction in the wild within the next 20 to 25 years. Ring-tailed lemurs are an iconic flagship species. Collectively, lemurs exemplify the biodiverse fauna of Madagascar and have facilitated the emergence of eco-tourism. In addition, conservation organizations increasingly seek to implement community-based approaches to save lemur species and promote sustainability.

Etymology

The name lemur is derived from the Latin term lemures,[7] which refers to specters or ghosts that were exorcised during the Lemuria festival of ancient Rome.[8][9] Linnaeus was familiar with the works of Virgil and Ovid, both of whom mentioned lemures. Seeing an analogy that fit with his naming scheme, he adapted the term "lemur" for these nocturnal primates.[10]

It was noted in 2012 that many sources had commonly and falsely assumed that Linnaeus was referring to the ghost-like appearance,

Lemures dixi hos, quod noctu imprimis obambulant, hominibus quodanmodo similes, & lento passu vagantur.

I call them lemurs, because they go around mainly by night, in a certain way similar to humans, and roam with a slow pace.

— Carl Linnaeus, Museum Adolphi Friderici Regis[13]

Evolutionary history

Lemurs are primates belonging to the suborder

Once part of the supercontinent

Distribution and diversity

Lemurs have

Lemurs lack any shared traits that make them stand out from all other primates.

Before the arrival of humans roughly 1500 to 2000 years ago, lemurs were found all across the island.

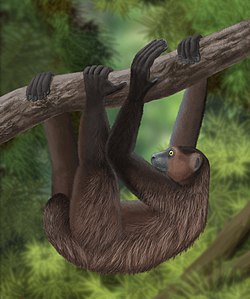

Until recently, giant lemurs existed on Madagascar. Now represented only by recent or subfossil remains, they were modern forms that were once part of the rich lemur diversity that has evolved in isolation. Some of their adaptations were unlike those seen in their living relatives.[29] All 17 extinct lemurs were larger than the extant (living) forms, some weighing as much as 200 kg (440 lb),[7] and are thought to have been active during the day.[38] Not only were they unlike the living lemurs in both size and appearance, they also filled ecological niches that either no longer exist or are now left unoccupied.[29] Large parts of Madagascar, which are now devoid of forests and lemurs, once hosted diverse primate communities that included more than 20 lemur species covering the full range of lemur sizes.[39]

Taxonomic classification and phylogeny

| Competing lemur phylogenies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There are two competing lemur phylogenies, one by Horvath et al. (top)[40] and one by Orlando et al. (bottom).[41] Note that Horvath et al. did not attempt to place the subfossil lemurs. |

From a taxonomic standpoint, the term "lemur" originally referred to the genus Lemur, which currently contains only the ring-tailed lemur. The term is now used in the colloquial sense in reference to all Malagasy primates.[42]

Lemur taxonomy is controversial, and not all experts agree, particularly with the recent increase in the number of recognized species.[33][43][44] According to Russell Mittermeier, the president of Conservation International (CI), taxonomist Colin Groves, and others, there are nearly 100 recognized species or subspecies of extant (or living) lemur, divided into five families and 15 genera.[45] Because genetic data indicates that the recently extinct subfossil lemurs were closely related to living lemurs,[46] an additional three families, eight genera, and 17 species can be included in the total.[31][36] In contrast, other experts have labeled this as taxonomic inflation,[44] instead preferring a total closer to 50 species.[33]

The classification of lemurs within the suborder Strepsirrhini is equally controversial, although most experts agree on the same phylogenetic tree. In one taxonomy, the infraorder Lemuriformes contains all living strepsirrhines in two superfamilies, Lemuroidea for all lemurs and Lorisoidea for the lorisoids (lorisids and galagos).[1][47] Alternatively, the lorisoids are sometimes placed in their own infraorder, Lorisiformes, separate from the lemurs.[48] In another taxonomy published by Colin Groves, the aye-aye was placed in its own infraorder, Chiromyiformes, while the rest of the lemurs were placed in Lemuriformes and the lorisoids in Lorisiformes.[49]

Although it is generally agreed that the aye-aye is the most basal member of the lemur clade, the relationship between the other four families is less clear since they diverged during a narrow 10 to 12 million-year window between the Late Eocene (42 mya) and into the Oligocene (30 mya).[20][26] The two main competing hypotheses are shown in the adjacent image.

| 2 infraorders[47] | 3 infraorders[48] | 4 infraorders[49] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Lemur taxonomy has changed significantly since the first taxonomic classification of lemurs by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. One of the greatest challenges has been the classification of the aye-aye, which has been a topic of debate up until very recently.[7] Until Richard Owen published a definitive anatomical study in 1866, early naturalists were uncertain whether the aye-aye (genus Daubentonia) was a primate, rodent, or marsupial.[50][51][52] However, the placement of the aye-aye within the order Primates remained problematic until very recently. Based on its anatomy, researchers have found support for classifying the genus Daubentonia as a specialized indriid, a sister group to all strepsirrhines, and as an indeterminate taxon within the order Primates.[19] Molecular tests have now shown Daubentoniidae is basal to all Lemuriformes,[19][53] and in 2008, Russell Mittermeier, Colin Groves, and others ignored addressing higher-level taxonomy by defining lemurs as monophyletic and containing five living families, including Daubentoniidae.[45]

Relationships among lemur families have also proven to be problematic and have yet to be definitively resolved.

More taxonomic changes have occurred at the genus level, although these revisions have proven more conclusive, often supported by genetic and molecular analysis. The most noticeable revisions included the gradual split of a broadly defined genus Lemur into separate genera for the ring-tailed lemur, ruffed lemurs, and brown lemurs due to a host of morphological differences.[58][59]

Due to several taxonomic revisions by Russell Mittermeier, Colin Groves, and others, the number of recognized lemur species has grown from 33 species and subspecies in 1994 to approximately 100 in 2008.

Anatomy and physiology

Lemurs vary greatly in size. They include the smallest primates in the world and, until recently, also included some of the largest. They currently range in size from about 30 g (1.1 oz) for

Like all primates, lemurs have five divergent

Additional traits shared with other

Lemurs are a diverse group of primates in terms of morphology and physiology.

Lemurs are unusual since they have great variability in their social structure, yet generally lack

Dentition

The lemur

| Family | Deciduous dental formula[56][74] | Permanent dental formula[42][51][75][76] |

|---|---|---|

| Cheirogaleidae, Lemuridae | 2.1.32.1.3 × 2 = 24 | 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 × 2 = 36 |

Lepilemuridae |

2.1.32.1.3 × 2 = 24 | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 × 2 = 32 |

| † Archaeolemuridae |

2.1.32.0.3 × 2 = 22 | 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 × 2 = 34 |

| † Megaladapidae |

1.1.32.1.3 × 2 = 22 | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 × 2 = 32 |

Palaeopropithecidae |

2.1.22.1.3 × 2 = 22[a] | 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 × 2 = 30[b] |

Daubentoniidae |

1.1.21.1.2 × 2 = 16 | 1.0.1.31.0.0.3 × 2 = 18 |

There are also noticeable differences in dental morphology and tooth topography between lemurs.

Only the aye-aye, the extinct giant aye-aye, and the largest of the extinct giant sloth lemurs lack a functional strepsirrhine toothcomb.[73][76] In the case of the aye-aye, the morphology of the deciduous incisors, which are lost shortly after birth, indicates that its ancestors had a toothcomb. These milk teeth are lost shortly after birth[81] and are replaced by open-rooted, continually growing (hypselodont) incisors.[73]

The toothcomb in lemurs normally consists of six teeth (four incisors and two canines), although indriids, monkey lemurs, and some sloth lemurs only have a four-tooth toothcomb due to the loss of either a pair of canines or incisors.[18][73] Because the lower canine is either included in the toothcomb or lost, the lower dentition can be difficult to read, especially since the first premolar (P2) is often shaped like a canine (caniniform) to fill the canine's role.[56] In folivorous (leaf-eating) lemurs, except for indriids, the upper incisors are greatly reduced or absent.[56][73] Used together with the toothcomb on the mandible (lower jaw), this complex is reminiscent of an ungulate browsing pad.[73]

Lemurs are unusual among primates for their rapid dental development, particularly among the largest species. For example, indriids have relatively slow body growth but extremely fast tooth formation and

Lemurs generally have thin

Senses

The sense of smell, or

The wet nose, or rhinarium, is a trait shared with other strepsirrhines and many other mammals, but not with haplorrhine primates.[51] Although it is claimed to enhance the sense of smell,[64] it is actually a touch-based sense organ that connects with a well-developed vomeronasal organ (VNO). Since pheromones are usually large, non-volatile molecules, the rhinarium is used to touch a scent-marked object and transfer the pheromone molecules down the philtrum (the nasal mid-line cleft) to the VNO via the nasopalatine ducts that travel through the incisive foramen of the hard palate.[16]

To communicate with smell, which is useful at night, lemurs will

Lemurs (and strepsirrhines in general) are considered to be less visually oriented than the higher primates, since they rely so heavily on their sense of smell and pheromone detection. The

| Angle between eyes | Binocular field | Combined field(binocular + periphery) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lemurs | 10–15° | 114–130° | 250–280° |

| Anthropoid primates | 0° | 140–160° | 180–190° |

Although they lack a fovea, some

Since cone cells make color vision possible, the high prevalence of rod cells in lemur eyes suggest they have not evolved color vision.[16] The most studied lemur, the ring-tailed lemur, has been shown to have blue-yellow vision, but lacks the ability to distinguish red and green hues.[89] Due to polymorphism in opsin genes, which code for color receptivity, trichromatic vision may rarely occur in females of a few lemur species, such as Coquerel's sifaka (Propithecus coquereli) and the red ruffed lemur (Varecia rubra). Most lemurs, therefore, are either monochromats or dichromats.[16]

Most lemurs have retained the tapetum lucidum, a reflective layer of tissue in the eye, which is found in many vertebrates.[42] This trait is absent in haplorrhine primates, and its presence further limits the visual acuity in lemurs.[32][88] The strepsirrhine choroidal tapetum is unique among mammals because it is made up of crystalline riboflavin, and the resulting optical scattering is what limits visual acuity.[88] Although the tapetum is considered to be ubiquitous in lemurs, there appear to be exceptions among true lemurs, such as the black lemur and the common brown lemur, as well as the ruffed lemurs.[16][32][88] Since the riboflavins in the tapetum have a tendency to dissolve and vanish when processed for histological investigation, however, the exceptions are still debatable.[16]

Lemurs also have a third eyelid known as a

Metabolism

Lemurs have low basal metabolic rates (BMR), which helps them to conserve energy during the dry season, when water and food are scarce.[2][67] They can optimize their energy use by lowering their metabolic rate to 20% below the values predicted for mammals of similar body mass.[92] The red-tailed sportive lemur (Lepilemur ruficaudatus), for instance, reportedly has one of the lowest metabolic rates among mammals. Its low metabolic rate may be linked to its generally folivorous diet and relatively small body mass.[67] Lemurs exhibit behavioral adaptations to complement this trait, including sunning behaviors, hunched sitting, group huddling, and nest sharing, in order to reduce heat loss and conserve energy.[92] Dwarf lemurs and mouse lemurs exhibit seasonal cycles of dormancy to conserve energy.[92] Before dry season, they will accumulate fat in white adipose tissue located at the base of the tail and hind legs, doubling their weight.[30][93][94] At the end of the dry season, their body mass may fall to half of what it was prior to the dry season.[30] Lemurs that do not experience states of dormancy are also able to shut down aspects of their metabolism for energy conservation.[92]

Behaviour

Lemur behaviour is as variable as lemur morphology. Differences in diet, social systems, activity patterns, locomotion, communication, predator avoidance tactics, breeding systems, and intelligence levels help define lemur taxa and set individual species apart from the rest. Although trends frequently distinguish the smaller, nocturnal lemurs from the larger, diurnal lemurs, there are often exceptions that help exemplify the unique and diverse nature of these Malagasy primates.

Diet

Lemur diets are highly variable and demonstrate a high degree of plasticity,[95] although general trends suggest that the smallest species primarily consume fruit and insects (omnivory), while the larger species are more herbivorous, consuming mostly plant material.[38] As with all primates, hungry lemurs might eat anything that is edible, whether or not the item is one of their preferred foods.[16] For instance, the ring-tailed lemur eats insects and small vertebrates when necessary[38][58] and as a result it is commonly viewed as an opportunistic omnivore.[73] Coquerel's giant mouse lemur (Mirza coquereli) is mostly frugivorous, but will consume insect secretions during the dry season.[38]

A common assumption in mammalogy is that small mammals cannot subsist entirely on plant material and must have a high-calorie diet in order to survive. As a result, it was thought that the diet of tiny primates must be high in protein-containing insects (insectivory). Research has shown, however, that mouse lemurs, the smallest living primates, consume more fruit than insects, contradicting the popular hypothesis.[16][38]

Plant material makes up the majority of most lemur diets. Members of at least 109 of all known plant families in Madagascar (55%) are exploited by lemurs. Since lemurs are primarily arboreal, most of these exploited species are woody plants, including trees, shrubs, or lianas. Only the ring-tailed lemur, the bamboo lemurs (genus Hapalemur), and the black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata) are known to consume herbs. While Madagascar is rich in fern diversity, these plants are rarely eaten by lemurs. One possible reason for this is that ferns lack flowers, fruits, and seeds—common food items in lemur diets. They also occur close to the ground, while lemurs spend most of their time in the trees. Lastly, ferns have an unpleasant taste due to the high content of tannins in their fronds. Likewise, mangroves appear to be rarely exploited by lemurs due to their high tannin content.[95] Some lemurs appear to have evolved responses against common plant defenses, however, such as tannins and alkaloids.[78] The golden bamboo lemur (Hapalemur aureus), for instance, eats giant bamboo (Cathariostachys madagascariensis), which contains high levels of cyanide. This lemur can consume twelve times the typically lethal dose for most mammals on a daily basis; the physiological mechanisms that protect it from cyanide poisoning are unknown.[2] At the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) in the United States, lemurs that roam the outdoor enclosures have been observed eating poison ivy (Taxicodendron radicans), yet have shown no ill effects.[63]

Many of the larger lemur species consume leaves (folivory),[95] particularly the indriids.[65] However, some smaller lemurs such as sportive lemurs (genus Lepilemur) and woolly lemurs (genus Avahi) also primarily eat leaves, making them the smallest primates that do so.[67] The smallest of the lemurs generally do not eat much leaf matter.[95] Collectively, lemurs have been documented consuming leaves from at least 82 native plant families and 15 alien plant families. Lemurs tend to be selective in their consumption of the part of the leaf or shoot as well as its age. Often, young leaves are preferred over mature leaves.[95]

Many lemurs that eat leaves tend to do so during times of fruit scarcity, sometimes suffering weight loss as a result.[96] Most lemur species, including most of the smallest lemurs and excluding some of the indriids, predominantly eat fruit (frugivory) when available. Collectively, lemurs have been documented consuming fruit from at least 86 native plant families and 15 alien plant families. As with most tropical fruit eaters, the lemur diet is dominated by fruit from Ficus (fig) species.[95] In many anthropoid primates, fruit is a primary source of vitamin C, but unlike anthropoid primates, lemurs (and all strepsirrhines) can synthesize their own vitamin C.[97] Historically, captive lemur diets high in vitamin C-rich fruits have been thought to cause hemosiderosis, a type of iron overload disorder, since vitamin C increases iron absorption. Although lemurs in captivity have been shown to be prone to hemosiderosis, the frequency of the disease varies across institutions and may depend on the diet, husbandry protocols, and genetic stock. Assumptions about the problem need to be tested separately for each species.[98] The ring-tailed lemur, for instance, seems to be less prone to the disorder than other lemur species.[99]

Only eight species of lemur are known to be seed predators (granivores), but this may be under-reported since most observations only report fruit consumption and do not investigate whether the seeds are consumed as well. These lemurs include some indriids, such as the diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), the golden-crowned sifaka (Propithecus tattersalli), the indri,[2][69] and the aye-aye. The aye-aye, which specializes in structurally defended resources, can chew through Canarium seeds, which are harder than the seeds that New World monkeys are known to break open.[50] At least 36 genera from 23 families of plants are targeted by lemur seed predators.[95]

Inflorescences (clusters of flowers) of at least 60 plant families are eaten by lemurs ranging in size from the tiny mouse lemurs to the relatively large ruffed lemurs. If the flowers are not exploited, sometimes the nectar is consumed (nectarivory) along with the pollen (palynivory). At least 24 native species from 17 plant families are targeted for nectar or pollen consumption.[95]

Bark and plant exudates such as

Soil consumption (

Social systems

Lemurs are social and live in groups that usually include fewer than 15 individuals.

Some lemurs exhibit female

The presence of female

There have been many hypotheses that have attempted to explain why lemurs exhibit female social dominance while other primates with similar social structures do not,[2][102] but no consensus has been reached after decades of research. The dominant view in the literature states that female dominance is an advantageous trait given the high costs of reproduction and the scarcity of resources available.[102] Indeed, female dominance has been shown to be linked to increased maternal investment.[103] However, when reproductive costs and extreme seasonality of resources were compared across primates, other primates demonstrated male dominance under conditions that were similar to or more challenging than those faced by lemurs. In 2008, a new hypothesis revised this model using simple game theory. It was argued that when two individuals were equally matched in fighting capacity, the one with the most need would win the conflict since it would have the most to lose. Consequently, the female, with higher resource needs for pregnancy, lactation, and maternal care, was more likely to win in resource conflicts with equally sized males. This, however, assumed monomorphism between sexes.[102] The following year, a new hypothesis was proposed to explain monomorphism, stating that because most female lemurs are only sexually receptive for a day or two each year, males can utilize a more passive form of mate guarding: copulatory plugs, which block the female reproductive tract, preventing other males from successfully mating with her, and thus reducing the need for aggression and the evolutionary drive for sexual dimorphism.[34]

In general, levels of agonism (or aggression) tend to correlate with relative canine height. The ring-tailed lemur has long, sharp upper canine teeth in both sexes, and it also exhibits high levels of agonism. The Indri, on the other hand, has smaller canines and exhibits lower levels of aggression.[32] When neighboring groups of the same species defend their territories, the conflict can take the form of ritualized defense. In sifakas, these ritualized combats involve staring, growling, scent-marking, and leaping to occupy certain sections of the tree. The indri defends its home range with ritualized "singing" battles.[2]

Like other primates, lemurs groom socially (allogroom) to ease tensions and solidify relationships. They groom in greeting, when waking up, when settling in for sleep, between mother and infant, in juvenile relations, and for sexual advances.[106] Unlike anthropoid primates, who part the fur with the hands and pick out particles with the fingers or mouth, lemurs groom with their tongue and scraping with their toothcomb.[2][106] Despite the differences in technique, lemurs groom with the same frequency and for the same reasons as anthropoids.[106]

Activity patterns

The

In order to conserve energy and water in their highly seasonal environment,[92][109] mouse lemurs and dwarf lemurs exhibit seasonal behavioral cycles of dormancy where the metabolic rate and body temperature are lowered. They are the only primates known to do so.[92] They accumulate fat reserves in their hind legs and the base of their tail before the dry winter season, when food and water are scarce,[30][93] and can exhibit daily and prolonged torpor during the dry season. Daily torpor constitutes less than 24 hours of dormancy, whereas prolonged torpor averages two weeks in duration and signals hibernation.[92] Mouse lemurs have been observed experiencing torpor that lasts for several consecutive days, but dwarf lemurs are known to hibernate for six to eight months every year,[29][30][94] particularly on the west coast of Madagascar.[109]

Dwarf lemurs are the only primates known to hibernate for extended periods.

Other lemurs that do not exhibit dormancy conserve energy by selecting thermoregulated microhabitats (such as tree holes), sharing nests, and reducing exposed body surfaces, such as by hunched sitting and group huddling. Also, the ring-tailed lemur, ruffed lemurs, and sifakas are commonly seen sunning, thus using solar radiation to warm their bodies instead of metabolic heat.[92]

Locomotion

The jumping prowess of the indriids has been well documented and is popular among

Communication

Lemur communication can be transmitted through sound, sight, and smell (

Olfaction is particularly important to lemurs,

Compared to other mammals, primates in general are very vocal, and lemurs are no exception.[16] Some lemur species have extensive vocal repertoires, including the ring-tailed lemur and ruffed lemurs.[89][117] Some of the most common calls among lemurs are predator alarm calls. Lemurs not only respond to alarm calls of their own species, but also alarm calls of other species and those of non-predatory birds. The ring-tailed lemur and a few other species have different calls and reactions to specific types of predators.[38] With mating calls, it has been shown that mouse lemurs that cannot be discerned visually respond more strongly to the calls of their own species, particularly when exposed to the calls of other mouse lemurs that they would encounter normally within their home range.[72] Lemur calls can also be very loud and carry long distances. Ruffed lemurs use several loud calls that can be heard up to 1 km (0.62 mi) away on a clear, calm day.[117] The loudest lemur is the indri, whose calls can be heard up to 2 km (1.2 mi) or more[51][62] and thus communicate more effectively the territorial boundaries over its 34 to 40 hectares (0.13 to 0.15 sq mi) home range.[78] Both ruffed lemurs and the indri exhibit contagious calling, where one individual or group starts a loud call and others within the area join in.[62][117] The song of the indri can last 45 seconds to more than 3 minutes and tends to coordinate to form a stable duet comparable to that of gibbons.[62][67]

Tactile communication (touch) is mostly used by lemurs in the form of grooming, although the ring-tailed lemur also clumps together to sleep (in an order determined by rank), reaches out and touches adjacent members, and cuffs other members. Reaching out and touching another individual in this species has been shown to be a submissive behavior, done by younger or submissive animals towards older and more dominant members of the troop. Allogrooming, however, appears to occur more frequently between higher ranking individuals, a shared trait with other primate species.[118] Unlike anthropoid primates, lemur grooming seems to be more intimate and mutual, often directly reciprocated. Anthropoids, on the other hand, use allogrooming to manage agonistic interactions.[119] The ring-tailed lemur is known to be very tactile, spending between 5 and 11% of its time grooming.[118]

Predator avoidance

All lemurs experience some predation pressure.

Diurnal lemurs are visible during the day, so many live in groups, where the increased number of eyes and ears helps aid in predator detection. Diurnal lemurs use and respond to alarm calls, even those of other lemur species and non-predatory birds. The ring-tailed lemur has different calls and reactions to different classes of predators, such as predatory birds, mammals, or snakes.[38] Some lemurs, such as the indri, use crypsis to camouflage themselves. They are often heard but difficult to see in the trees due to the dappled light, earning them the reputation of being "ghosts of the forest".[78]

Reproduction

Except for the aye-aye and the Lac Alaotra gentle lemur, lemurs are seasonal breeders

Lemurs time their mating and birth seasons so that all weaning periods are synchronized to match the time of highest food availability.[85][96] Weaning occurs either before or shortly after the eruption of the first permanent molars in lemurs.[32] Mouse lemurs are able to fit their entire breeding cycle into the wet season, whereas larger lemurs, such as sifakas, must lactate for two months during the dry season.[96] Infant survival in some species, such as Milne-Edwards' sifaka, has been shown to be directly impacted by both environmental conditions and the rank, age, and health of the mother. The breeding season is also affected by geographical location. For example, mouse lemurs give birth between September and October in their native habitat in the Southern Hemisphere, but from May through June in the captive settings in the Northern Hemisphere.[85]

The

After the offspring are born, lemurs either carry them around or stash them while foraging. When transported, the infants either cling to the mother's fur or are carried in the mouth by the scruff. In some species, such as bamboo lemurs, infants are carried by mouth until they are able to cling to their mother's fur.

Yet another trait that sets most lemurs apart from anthropoid primates is their long lifespan together with their high infant mortality.[96] Many lemurs, including the ring-tailed lemur, have adapted to a highly seasonal environment, which has affected their birthrate, maturation, and twinning rate (r-selection). This helps them to recover rapidly from a population crash.[89] In captivity, lemurs can live twice as long as they do in the wild, benefiting from consistent nutrition that meets their dietary requirements, medical advancements, and improved understanding of their housing requirements. In 1960, it was thought that lemurs could live between 23 and 25 years. It is now known that the larger species can live for more than 30 years without showing signs of aging (senescence) and still be capable of reproduction.[85]

Cognitive abilities and tool use

Lemurs have traditionally been regarded as being less intelligent than anthropoid primates,

A few lemurs have been noted to have relatively large brains. The extinct Hadropithecus was as large as a large male baboon and had a comparably sized brain, giving it the largest brain size relative to body size among all prosimians.[131] The aye-aye also has a large brain-to-body ratio, which may indicate a higher level of intelligence.[42] However, despite having a built-in tool in the form of its thin, elongated middle finger, which it uses to fish for insect grubs, the aye-aye has tested poorly in the use of extraneous tools.[16]

Ecology

- See above: Diet, Metabolism, Activity patterns, and Locomotion

Madagascar not only contains two radically different climatic zones, the rainforests of the east and the dry regions of the west,[2] but also swings from extended drought to cyclone-generated floods.[132] These climatic and geographical challenges, along with poor soils, low plant productivity, wide ranges of ecosystem complexity, and a lack of regularly fruiting trees (such as fig trees) have driven the evolution of lemurs' immense morphological and behavioral diversity.[15][2][32][96] Their survival has required the ability to endure the persistent extremes, not yearly averages.[132]

Lemurs have either presently or formerly filled the

Dietary regimes of lemurs include folivory, frugivory, and omnivory, with some being highly adaptable while others specialize on foods such as plant exudates (tree gum) and bamboo.[133] In some cases, lemur feeding patterns directly benefit the native plant life. When lemurs exploit nectar, they may act as pollinators as long as the functional parts of the flower are not damaged.[95] In fact, several unrelated Malagasy flowering plants demonstrate lemur-specific pollination traits, and studies indicate that some diurnal species, such as the red-bellied lemur and the ruffed lemurs, act as major pollinators.[2] Two examples of plant species that rely on lemurs for pollination include traveller's palm (Ravenala madagascariensis)[59] and a species of legume-like liana, Strongylodon cravieniae.[2] Seed dispersal is another service lemurs provide. After passing through the lemur gut, tree and vine seeds exhibit lower mortality and germinate faster.[96] Latrine behavior exhibited by some lemurs may help improve soil quality and facilitate seed dispersal.[16] Because of their importance in maintaining a healthy forest, frugivorous lemurs may qualify as keystone mutualists.[96]

All lemurs, particularly the smaller species, are affected by predation

Research

Similarities that lemurs share with anthropoid primates, such as diet and social organization, along with their own unique traits, have made lemurs the most heavily studied of all mammal groups on Madagascar.[2][61] Research often focuses on the link between ecology and social organization, but also on their behavior and morphophysiology (the study of anatomy in relation to function).[2] Studies of their life-history traits, behavior and ecology help understanding of primate evolution, since they are thought to share similarities with ancestral primates.

Lemurs have been the focus of

Lemurs are mentioned in sailors' voyage logs as far back as 1608 and in 1658 that at least seven lemur species were described in detail by the French merchant,

During the 19th century, there was an explosion of new lemur descriptions and names, which later took decades to sort out. During this time, professional collectors gathered specimens for museums, menageries, and cabinets. Some of the major collectors were Johann Maria Hildebrandt and Charles Immanuel Forsyth Major. From these collections, as well as increasing observations of lemurs in their natural habitats, museum systematists including Albert Günther and John Edward Gray continued to contribute new names for new lemur species. However, the most notable contributions from this century includes the work of Alfred Grandidier, a naturalist and explorer who devoted himself to the study of Madagascar's natural history and local people. With the help of Alphonse Milne-Edwards, most of the diurnal lemurs were illustrated at this time. However, lemur taxonomic nomenclature took its modern form in the 1920s and 1930s, being standardized by Ernst Schwarz in 1931.[132][134]

Although lemur taxonomy had developed, it was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the in-situ (or on-site) study of lemur behavior and ecology began to blossom.

Ex situ research (or off-site research) is also popular among researchers looking to answer questions that are difficult to test in the field. For example, efforts to

Conservation

Lemurs are threatened by a host of environmental problems, including

Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world,[150][151] with a high population growth rate of 2.5% per year and nearly 70% of the population living in poverty.[38][150] The country is also burdened with high levels of debt and limited resources.[151] These socioeconomic issues have complicated conservation efforts, even though the island of Madagascar has been recognized by IUCN/SSC as a critical primate region for over 20 years.[144] Due to its relatively small land area—587,045 km2 (226,659 sq mi)—compared to other high-priority biodiversity regions and its high levels of endemism, the country is considered one of the world's most important biodiversity hotspots, with lemur conservation being a high priority.[135][144] Despite the added emphasis for conservation, there is no indication that the extinctions that began with the arrival of humans have come to an end.[37]

Threats in the wild

The greatest concern facing lemur populations is habitat destruction and degradation.

Some species may be in risk of extinction even without complete deforestation, such as ruffed lemurs, which are very sensitive to habitat disturbance.[61] If large fruit trees are removed, the forest may sustain fewer individuals of a species and their reproductive success may be affected for years.[96] Small populations may be able to persist in isolated forest fragments for 20 to 40 years due to long generation times, but in the long term, such populations may not be viable.[152] Small, isolated populations also risk extirpation by natural disasters and disease outbreaks (epizootics). Two diseases that are lethal to lemurs and could severely impact isolated lemur populations are toxoplasmosis, which is spread by feral cats, and the herpes simplex virus carried by humans.[153]

Lemurs are hunted for food by the local Malagasy, either for local subsistence[7][142] or to supply a luxury meat market in the larger cities.[155] Most rural Malagasy do not understand what "endangered" means, nor do they know that hunting lemurs is illegal or that lemurs are found only in Madagascar.[156] Many Malagasy have taboo, or fady, about hunting and eating lemurs, but this does not prevent hunting in many regions.[2] Even though hunting has been a threat to lemur populations in the past, it has recently become a more serious threat as socioeconomic conditions deteriorate.[142] Economic hardships have caused people to move around the country in search of employment, leading local traditions to break down.[61][143][156] Drought and famine can also relax the fady that protect lemurs.[61] Larger species, such as sifakas and ruffed lemurs, are common targets, but smaller species are also hunted or accidentally caught in snares intended for larger prey.[7][143] Experienced, organized hunting parties using firearms, slings and blowguns can kill as many as eight to twenty lemurs in one trip. Organized hunting parties and lemur traps can be found in both non-protected areas and remote corners of protected areas.[61] National parks and other protected areas are not adequately protected by law enforcement agencies.[156] Often, there are too few park rangers to cover a large area, and sometimes terrain within the park is too rugged to check regularly.[157]

Although not as significant as deforestation and hunting, some lemurs, such as crowned lemurs and other species that have successfully been kept in captivity, are occasionally kept as exotic pets by Malagasy people.[51][135] Bamboo lemurs are also kept as pets,[135] although they only survive for up to two months.[158] Live capture for the exotic pet trade in wealthier countries is not normally considered a threat due to strict regulations controlling their export.[135][143]

Conservation efforts

Lemurs have drawn much attention to Madagascar and its endangered species. In this capacity, they act as flagship species,[61][135] the most notable of which is the ring-tailed lemur, which is considered an icon of the country.[59] The presence of lemurs in national parks helps drive ecotourism,[135] which especially helps local communities living in the vicinity of the national parks, since it offers employment opportunities and the community receives half of the park entrance fees. In the case of Ranomafana National Park, job opportunities and other revenue from long-term research can rival that of ecotourism.[159]

Starting in 1927, the

Conservation is also facilitated by the

Debt relief may help Madagascar protect its biodiversity.[151] With the political crisis in 2009, illegal logging has proliferated and now threatens rainforests in the northeast, including its lemur inhabitants and the ecotourism that the local communities rely upon.[needs update]

Captive lemur populations are maintained locally and outside of Madagascar in varied zoological conservatories and research centers, although the diversity of species is limited. Sikafas, for instance, do not survive well in captivity, so few facilities have them.

In Malagasy culture

In Malagasy culture, lemurs, and animals in general, have souls (ambiroa) which can get revenge if mocked while alive or if killed in a cruel fashion. Because of this, lemurs, like many other elements of daily life, have been a source of taboos, known locally as fady, which can be based around stories with four basic principles. A village or region may believe that a certain type of lemur may be the ancestor of the clan. They may also believe that a lemur's spirit may get revenge. Alternatively, the animal may appear as a benefactor. Lemurs are also thought to impart their qualities, good or bad, onto human babies.[164] In general, fady extend beyond a sense of the forbidden, but can include events that bring bad luck.[81]

One example of lemur fady told around 1970 comes from Ambatofinandrahana in the Fianarantsoa Province. According to the account, a man brought a lemur home in a trap, but alive. His children wanted to keep the lemur as a pet, but when the father told them it was not a domestic animal, the children asked to kill it. After the children tortured the lemur, it eventually died and was eaten. A short time later, all the children died of illness. As a result, the father declared that anyone who tortures lemurs for fun shall "be destroyed and have no descendants."[164]

Fady can not only help protect lemurs and their forests under stable

The aye-aye is almost universally viewed unfavorably across Madagascar,[81] though the tales vary from village to village and region to region. If people see an aye-aye, they may kill it and hang the corpse on a pole near a road outside of town (so others can carry the bad fortunes away) or burn their village and move.[52][70] The superstitions behind aye-aye fady include beliefs that they kill and eat chickens or people, that they kill people in their sleep by cutting their aortic vein,[61] that they embody ancestral spirits,[70] or that they warn of illness, death, or bad luck in the family.[51][52] As of 1970, the people of the Marolambo District in the Toamasina Province feared the aye-aye because they believed it had supernatural powers. Because of this, no one was allowed to mock, kill, or eat one.[164]

There are also widespread fady about indri and sifakas. They are often protected from hunting and consumption because of their resemblance to humans and their ancestors, mostly due to their large size and upright or orthograde posture. The resemblance is even stronger for indri, which lack the long tail of most living lemurs.[62][82] Known locally as babakoto ("Ancestor of Man"), the indri is sometimes seen as the progenitor of the family or clan. There are also stories of an indri that helped a human down from a tree, so they are seen as benefactors.[164] Other lemur fady include the belief that a wife will have ugly children if her husband kills a woolly lemur, or that if a pregnant woman eats a dwarf lemur, her baby will get its beautiful, round eyes.[164]

In popular culture

Lemurs have also become popular in

Notes

- ^ No infant Mesopropithecus, Babakotia, or Archaeoindris remains have been found, and little is known about the deciduous dentition of Palaeopropithecus. Developmental patterns are inferred from the developmental patterns of their closest relatives, the indriids.[77]

- ^ In indriids, either a pair of deciduous lower incisors or lower canines are not replaced in permanent dentition. Differing interpretations of this yield different dental formulae. Therefore an alternative dental formula for this family is 2.1.2.31.1.2.3 × 2 = 30.[56]

References

Citations

- ^ S2CID 24163044.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Sussman 2003, pp. 149–229.

- ^ "IUCN 2014". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2012. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ^ Linnaeus 1758, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Tattersall 1982, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Garbutt 2007, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Lux, J. (2008). "What are lemures?" (PDF). Humanitas. 32 (1): 7–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2010.

- ^ Ley, Willy (August 1966). "Scherazade's Island". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 45–55.

- ^ Blunt & Stearn 2002, p. 252.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ Nield 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Linnaeus 1754, p. 4.

- ^ S2CID 220087294.

- ^ a b c Gould & Sauther 2006, pp. vii–xiii.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 392–514.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Preston-Mafham 1991, pp. 141–188.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tattersall 2006, pp. 3–18.

- ^ a b c d e f Yoder 2003, pp. 1242–1247.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ^ Flynn & Wyss 2003, pp. 34–40.

- ^ a b c d Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 23–26.

- from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ Garbutt 2007, pp. 14–15.

- doi:10.1038/news.2010.23. Archived from the originalon 16 March 2011.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2013-08-24. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ^ Krause 2003, pp. 40–47.

- ^ S2CID 4333977.

- "Animals populated Madagascar by rafting there". ScienceDaily (Press release). 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sussman 2003, pp. 107–148.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 89–182.

- ^ a b c d Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 37–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Godfrey, Jungers & Schwartz 2006, pp. 41–64.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ^ S2CID 13617914.

- "New Theory On Why Male, Female Lemurs Same Size: 'Passive' Mate Guarding Influenced Evolution Of Lemur Size". ScienceDaily (Press release). 1 August 2009. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Preston-Mafham 1991, pp. 10–21.

- ^ .

- "New Extinct Lemur Species Discovered In Madagascar". ScienceDaily (Press release). 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Burney 2003, pp. 47–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Sussman 2003, pp. 257–269.

- ^ a b Godfrey & Jungers 2003, pp. 1247–1252.

- ^ Horvath et al. 2008, fig. 1.

- ^ Orlando et al. 2008, fig. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rowe 1996, p. 27.

- PMID 19193227.

- ^ S2CID 54727842.

- ^ S2CID 17614597. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-08-27. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- (PDF) from the original on 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ^ a b Cartmill 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b Hartwig 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Groves 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Sterling & McCreless 2006, pp. 159–184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 48–161.

- ^ a b c Garbutt 2007, pp. 205–207.

- ^ PMID 8952078.

- S2CID 10585152.

- ^ PMID 18442367.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 224–283.

- ^ a b Garbutt 2007, pp. 115–136.

- ^ a b c Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 209–323.

- ^ a b c Garbutt 2007, pp. 137–175.

- ^ a b Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 85–88.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Goodman, Ganzhorn & Rakotondravony 2003, pp. 1159–1186.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thalmann & Powzyk 2003, pp. 1342–1345.

- ^ a b c d e f Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 284–391.

- ^ a b c d Rowe 1996, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Garbutt 2007, pp. 176–204.

- ^ a b Thalmann 2003, pp. 1340–1342.

- ^ a b c d e Thalmann & Ganzhorn 2003, pp. 1336–1340.

- ^ a b c Nowak 1999, pp. 84–89.

- ^ a b c Richard 2003, pp. 1345–1348.

- ^ a b c d e Sterling 2003, pp. 1348–1351.

- ^ a b c d e Overdorff & Johnson 2003, pp. 1320–1324.

- ^ PMID 18462484.

- "It Started With A Squeak: Moonlight Serenade Helps Lemurs Pick Mates Of The Right Species". ScienceDaily (Press release). 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cuozzo & Yamashita 2006, pp. 67–96.

- ^ a b Lamberton, C. (1938). "Dentition de lait de quelques lémuriens subfossiles malgaches". Mammalia. 2: 57–80.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 1994, pp. 33–48.

- ^ a b Godfrey & Jungers 2002, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Godfrey, Petto & Sutherland 2001, pp. 113–157.

- ^ a b c d e f Powzyk & Mowry 2006, pp. 353–368.

- ^ Osman Hill 1953, p. 73.

- ^ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 421–423.

- ^ ISSN 0343-3528. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b Irwin 2006, pp. 305–326.

- ^ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 206–223.

- ^ a b Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 162–205.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 521–532.

- ^ a b Ross & Kay 2004, pp. 3–41.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d Kirk & Kay 2004, pp. 539–602.

- ^ a b c d e f Jolly 2003, pp. 1329–1331.

- ^ Osman Hill 1953, p. 13.

- ^ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 470–471.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schmid & Stephenson 2003, pp. 1198–1203.

- ^ a b Nowak 1999, pp. 65–71.

- ^ a b c Fietz 2003, pp. 1307–1309.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Birkinshaw & Colquhoun 2003, pp. 1207–1220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wright 2006, pp. 385–402.

- S2CID 24628550.

- S2CID 11802617.

- S2CID 32652173.

- ^ a b Sussman 2003, pp. 3–37.

- S2CID 46767773.

- ^ S2CID 13602663.

- ^ S2CID 85004340.

- ^ Tan 2006, pp. 369–382.

- S2CID 19508316.

- ^ S2CID 29181662.

- ^ a b Curtis 2006, pp. 133–158.

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 187–210.

- ^ a b c d Fietz & Dausmann 2006, pp. 97–110.

- ^ Garbutt 2007, pp. 86–114.

- (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ^ Nowak 1999, pp. 71–81.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 324–403.

- S2CID 9175659.

- ^ Jolly 1966, p. 135.

- S2CID 21408447.

- ^ a b c Vasey 2003, pp. 1332–1336.

- ^ S2CID 33268904.

- S2CID 43896118.

- ^ a b c d e f Goodman 2003, pp. 1221–1228.

- S2CID 464977. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Crompton & Sellers 2007, pp. 127–145.

- PMID 18489230.

- ^ a b Kappeler & Rasoloarison 2003, pp. 1310–1315.

- ^ a b Mutschler & Tan 2003, pp. 1324–1329.

- ^ ISSN 1608-1439.

- S2CID 19790101.

- S2CID 10063588.

- .

- ^ Fichtel & Kappeler 2010, p. 413.

- ^ Penn State (29 July 2008). "Piecing together an extinct lemur, large as a big baboon". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Jolly & Sussman 2006, pp. 19–40.

- ISSN 1662-2510.

- ^ a b c Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 27–36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 52–84.

- PMID 7959437.

- S2CID 86156628.

- .

- PMID 19649139. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2010-06-20.

- PMID 18085919. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2010-04-20.

- (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b c d e Harcourt 1990, pp. 7–13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mittermeier, Konstant & Rylands 2003, pp. 1538–1543.

- ISBN 978-1-934151-34-1. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-12-31.

- ^ Black, R. (13 July 2012). "Lemurs sliding towards extinction". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Lemurs named world's most endangered mammals". LiveScience. 13 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Samuel, H. (19 August 2013). "Furry lemurs 'could be wiped out within 20 years'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Mintz, Z. (21 August 2013). "Lemurs face extinction in 20 years, risk of losing species for 'first time in two centuries'". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Country brief: Madagascar" (PDF). eStandardsForum. 1 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ a b c World Wildlife Fund (14 June 2008). "Monumental debt-for-nature swap provides $20 million to protect biodiversity in Madagascar". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ Ganzhorn, Goodman & Dehgan 2003, pp. 1228–1234.

- ^ Junge & Sauther 2006, pp. 423–440.

- ^ Ratsimbazafy 2006, pp. 403–422.

- ^ Butler, Rhett (4 January 2010). "Madagascar's political chaos threatens conservation gains". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Simons 1997, pp. 142–166.

- ^ Schuurman, Derek (June 2009). "Illegal logging in Madagascar" (PDF). Traffic Bulletin. 22 (2): 49. Archived from the original on 2019-04-17. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ^ Rowe 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Wright & Andriamihaja 2003, pp. 1485–1488.

- ^ a b Sargent & Anderson 2003, pp. 1543–1545.

- ^ Britt et al. 2003, pp. 1545–1551.

- ^ "Myakka City Lemur Reserve". Lemur Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 671–672.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ruud 1970, pp. 97–101.

- ^ Barnes, D. (October 21, 2001). "Fun in the sun with lemurs". The Washington Times.

- ^ Jacobson, Louis (March 30, 2004). "Looking for lemurs". USA Today. Archived from the original on 16 August 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ Huff, R. (February 8, 2008). "Tonight". New York Daily News. p. 122.

- ^ "Highlights". The Washington Post. February 8, 2008. p. C04.

- Africa News. December 28, 2007.

- ^ Walmark, H. (February 8, 2008). "Critic's choice: Lemur Street". The Globe and Mail. p. R37.

Books cited

- Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-372576-9.

- Blunt, W.; Stearn, W.T. (2002). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09636-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- Campbell, C. J.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K. C.; Bearder, S. K.; Stumpf, R. M, eds. (2011). Primates in Perspective (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539043-8.

- Hartwig, W. (2011). "Chapter 3: Primate evolution". Primates in Perspective. pp. 19–31.

- Crompton, Robin Huw; Sellers, William Irvin (2007). "A consideration of leaping locomotion as a means of predator avoidance in prosimian primates" (PDF). In Gursky, K.A.I.; Nekaris, S.L. (eds.). Primate Anti-Predator Strategies. Springer. pp. 127–145. S2CID 81109633. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-09-04. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- Fichtel, C.; Kappeler, P. M. (2010). "Chapter 19: Human universals and primate symplesiomorphies: Establishing the lemur baseline". In Kappeler, P. M.; Silk, J. B. (eds.). Mind the Gap: Tracing the Origins of Human Universals. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-02724-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- Garbutt, N. (2007). Mammals of Madagascar, A Complete Guide. A&C Black Publishers. ISBN 978-0-300-12550-4.

- Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P., eds. (2003). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2.

- Flynn, J.J.; Wyss, A.R. (2003). Mesozoic Terrestrial Vertebrate Faunas: The Early History of Madagascar's Vertebrate Diversity. pp. 34–40.

- Krause, D.W. (2003). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates of Madagascar: A Window into Gondwanan Biogeography at the End of the Age of Dinosaurs. pp. 40–47.

- Burney, D.A. (2003). Madagascar's Prehistoric Ecosystems. pp. 47–51.

- Goodman, S.M.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Rakotondravony, D. (2003). Introduction to the Mammals. pp. 1159–1186.

- Schmid, J.; Stephenson, P.J. (2003). Physiological Adaptations of Malagasy Mammals: Lemurs and Tenrecs Compared. pp. 1198–1203.

- Birkinshaw, C.R.; Colquhoun, I.C. (2003). Lemur Food Plants. pp. 1207–1220.

- Goodman, S.M. (2003). Predation on Lemurs. pp. 1221–1228.

- Ganzhorn, J. U.; Goodman, S. M.; Dehgan, A. (2003). Effects of Forest Fragmentation on Small Mammals and Lemurs. pp. 1228–1234.

- Yoder, A.D. (2003). Phylogeny of the Lemurs. pp. 1242–1247.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2003). Subfossil Lemurs. pp. 1247–1252.

- Fietz, J. (2003). Primates: Cheirogaleus, Dwarf Lemurs or Fat-tailed Lemurs. pp. 1307–1309.

- Kappeler, P.M.; Rasoloarison, R.M. (2003). Microcebus, Mouse Lemurs, Tsidy. pp. 1310–1315.

- Overdorff, D.J.; Johnson, S. (2003). Eulemur, True Lemurs. pp. 1320–1324.

- Mutschler, T.; Tan, C.L. (2003). Hapalemur, Bamboo or Gentle Lemur. pp. 1324–1329.

- Jolly, A. (2003). Lemur catta, Ring-tailed Lemur. pp. 1329–1331.

- Vasey, N. (2003). Varecia, Ruffed Lemurs. pp. 1332–1336.

- Thalmann, U.; Ganzhorn, J.U. (2003). Lepilemur, Sportive Lemur. pp. 1336–1340.

- Thalmann, U. (2003). Avahi, Woolly Lemurs. pp. 1340–1342.

- Thalmann, U.; Powzyk, J. (2003). Indri indri, Indri. pp. 1342–1345.

- Richard, A. (2003). Propithecus, Sifakas. pp. 1345–1348.

- Sterling, E. (2003). Daubentonia madagascariensis, Aye-aye. pp. 1348–1351.

- Wright, P.C.; Andriamihaja, B. (2003). The conservation value of long-term research: a case study from the Parc National de Ranomafana. pp. 1485–1488.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Konstant, W.R.; Rylands, A.B. (2003). Lemur Conservation. pp. 1538–1543.

- Sargent, E.L.; Anderson, D. (2003). The Madagascar Fauna Group. pp. 1543–1545.

- Britt, A.; Iambana, B.R.; Welch, C.R.; Katz, A.S. (2003). Restocking of Varecia variegata variegata in the Réserve Naturelle Intégrale de Betampona. pp. 1545–1551.

- Goodman, S.M.; Patterson, B.D., eds. (1997). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

- Simons, E.L. (1997). "Chapter 6: Lemurs: Old and New". Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. pp. 142–166.

- Gould, L.; Sauther, M.L., eds. (2006). Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-34585-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- Gould, L.; Sauther, M.L. (2006). "Preface". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. vii–xiii.

- Tattersall, I. (2006). "Chapter 1: Origin of the Malagasy Strepsirhine Primates". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 3–18.

- Jolly, A.; Sussman, R.W. (2006). "Chapter 2: Notes on the History of Ecological Studies of Malagasy Lemurs". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 19–40.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Schwartz, G.T. (2006). "Chapter 3: Ecology and Extinction of Madagascar's Subfossil Lemurs". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 41–64.

- Cuozzo, F.P.; Yamashita, N. (2006). "Chapter 4: Impact of Ecology on the Teeth of Extant Lemurs: A Review of Dental Adaptations, Function, and Life History". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 67–96.

- Fietz, J.; Dausmann, K.H. (2006). "Chapter 5: Big Is Beautiful: Fat Storage and Hibernation as a Strategy to Cope with Marked Seasonality in the Fat-Tailed Dwarf Lemur (Cheirogaleus medius)". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 97–110.

- Curtis, D.J. (2006). "Chapter 7: Cathemerality in Lemurs". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 133–158.

- Sterling, E.J.; McCreless, E.E. (2006). "Chapter 8: Adaptations in the Aye-aye: A Review". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 159–184.

- Johnson, S.E. (2006). "Chapter 9: Evolutionary Divergence in the Brown Lemur Species Complex". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 187–210.

- Irwin, M.T. (2006). "Chapter 14: Ecologically Enigmatic Lemurs: The Sifakas of the Eastern Forests (Propithecus candidus, P. diadema, P. edwardsi, P. perrieri, and P. tattersalli)". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 305–326.

- Powzyk, J.A.; Mowry, C.B. (2006). "Chapter 16: The Feeding Ecology and Related Adaptations of Indri indri". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 353–368.

- Tan, C.L. (2006). "Chapter 17: Behavior and Ecology of Gentle Lemurs (Genus Hapalemur)". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 369–382.

- Wright, P.C. (2006). "Chapter 18: Considering Climate Change Effects in Lemur Ecology". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 385–402.

- Ratsimbazafy, J. (2006). "Chapter 19: Diet Composition, Foraging, and Feeding Behavior in Relation to Habitat Disturbance: Implications for the Adaptability of Ruffed Lemurs (Varecia variegata editorium) in Manombo Forest, Madagascar". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 403–422.

- Junge, R.E.; Sauther, M. (2006). "Chapter 20: Overview on the Health and Disease Ecology of Wild Lemurs: Conservation Implications". Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. pp. 423–440.

- OCLC 62265494.

- Harcourt, C. (1990). Thornback, J (ed.). Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros: The IUCN Red Data Book – Introduction (PDF). World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-2-88032-957-0.

- Hartwig, W.C., ed. (2002). The primate fossil record. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66315-1.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2002). "Chapter 7: Quaternary fossil lemurs". The primate fossil record. pp. 97–121. Bibcode:2002prfr.book.....H.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2002). "Chapter 7: Quaternary fossil lemurs". The primate fossil record. pp. 97–121.

- ISBN 978-0-226-40552-0.

- Linnaeus, C. (1754). Museum Adolphi Friderici Regis. Stockholm: Typographia Regia. Archived from the original on 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae (in Latin). Vol. 1. Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- OCLC 32480729.

- OCLC 883321520.

- OCLC 670545286.

- Nield, T. (2007). Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02659-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Osman Hill, W.C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy I—Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science & Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 500576914.

- Platt, M.; Ghazanfar, A., eds. (2010). Primate Neuroethology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532659-8.

- Cartmill, M. (2010). Primate neuroethology - Chapter 2: Primate Classification and Diversity. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–30. ISBN 9780199716845. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- Cartmill, M. (2010). Primate neuroethology - Chapter 2: Primate Classification and Diversity. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–30.

- Plavcan, J.M.; Kay, R.; Jungers, W.L.; van Schaik, C., eds. (2001). Reconstructing behavior in the primate fossil record. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46604-5.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Petto, A.J.; Sutherland, M.R. (2001). "Chapter 4: Dental ontogeny and life history strategies: The case of the giant extinct indroids of Madagascar". Reconstructing behavior in the primate fossil record. pp. 113–157.

- Preston-Mafham, K. (1991). Madagascar: A Natural History. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-2403-2.

- Ross, C.F.; Kay, R.F., eds. (2004). Anthropoid Origins: New Visions (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-48120-8.

- Ross, C.F.; Kay, R.F. (2004). "Chapter 1: Evolving Perspectives on Anthropoidea". Anthropoid Origins: New Visions. pp. 3–41.

- Kirk, C.E.; Kay, R.F. (2004). "Chapter 22: The Evolution of High Visual Acuity in the Anthropoidea". Anthropoid Origins: New Visions. pp. 539–602.

- Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. Pogonias Press. ISBN 978-0-9648825-1-5.

- Ruud, J. (1970). Taboo: A Study of Malagasy Customs and Beliefs (2nd ed.). Oslo University Press. ASIN B0006FE92Y.

- Sussman, R.W. (2003). Primate Ecology and Social Structure. Pearson Custom Publishing. ISBN 978-0-536-74363-3.

- Szalay, F.S.; Delson, E. (1980). Evolutionary History of the Primates. from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- Tattersall, I. (1982). "Chapter: The Living Species of Malagasy Primates". The Primates of Madagascar. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04704-3.

External links

- Duke Lemur Center A research, conservation, and education facility

- Lemur Conservation Foundation A research, conservation, and education facility

- Lemurs of Madagascar Info about lemurs and the national parks they can be found in

- Bronx Zoo Presents Lemur Life A site created by the Wildlife Conservation Society that provides lemur videos, photos and educational tools for teachers and parents

- BBC Nature Lemurs: from the planet's smallest primate, the mouse lemur, to ring-tailed lemurs and indris. News, sounds and video.