Omar Khayyam

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm Nīsābūrī

As a mathematician, he is most notable for his work on the classification and solution of

There is a tradition of attributing

Life

Omar Khayyam was born in Nishapur—a metropolis in Khorasan province, of Persian stock, in 1048.[8][9][10][11][12] In medieval Persian texts he is usually simply called Omar Khayyam.[7]: 658 [c] Although open to doubt, it has often been assumed that his forebears followed the trade of tent-making, since Khayyam means 'tent-maker' in Arabic.[15]: 30 The historian Bayhaqi, who was personally acquainted with Khayyam, provides the full details of his horoscope: "he was Gemini, the sun and Mercury being in the ascendant[...]".[16]: 471 [17]: 172–175, no. 66 This was used by modern scholars to establish his date of birth as 18 May 1048.[7]: 658

Khayyam's boyhood was spent in Nishapur,

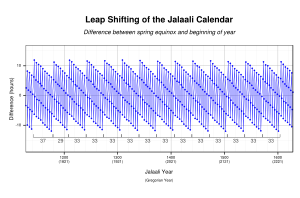

In 1073–4 peace was concluded with Sultan Malik-Shah I who had made incursions into Karakhanid dominions. Khayyam entered the service of Malik-Shah in 1074–5 when he was invited by the Grand Vizier Nizam al-Mulk to meet Malik-Shah in the city of Marv. Khayyam was subsequently commissioned to set up an observatory in Isfahan and lead a group of scientists in carrying out precise astronomical observations aimed at the revision of the Persian calendar. The undertaking began probably in 1076 and ended in 1079,[8]: 28–29 when Omar Khayyam and his colleagues concluded their measurements of the length of the year, reporting it as 365.24219858156 days.[5] Given that the length of the year is changing in the sixth decimal place over a person's lifetime, this is outstandingly accurate. For comparison the length of the year at the end of the 19th century was 365.242196 days, while today it is 365.242190 days.

After the death of Malik-Shah and his vizier (murdered, it is thought, by the

Omar Khayyam died at the age of 83 in his hometown of Nishapur on 4 December 1131, and he is buried in what is now the Mausoleum of Omar Khayyam. One of his disciples Nizami Aruzi relates the story that sometime during 1112–3 Khayyam was in Balkh in the company of Isfizari (one of the scientists who had collaborated with him on the Jalali calendar) when he made a prophecy that "my tomb shall be in a spot where the north wind may scatter roses over it".[15]: 36 [19] Four years after his death, Aruzi located his tomb in a cemetery in a then large and well-known quarter of Nishapur on the road to Marv. As it had been foreseen by Khayyam, Aruzi found the tomb situated at the foot of a garden-wall over which pear trees and peach trees had thrust their heads and dropped their flowers so that his tombstone was hidden beneath them.[15]: 37

Mathematics

Khayyam was famous during his life as a mathematician. His surviving mathematical works include (i) Commentary on the Difficulties Concerning the Postulates of Euclid's Elements (Risāla fī Sharḥ mā Ashkal min Muṣādarāt Kitāb Uqlīdis), completed in December 1077,[11]: 832a [23][24]: § 1 [25]: 324b (ii) Treatise On the Division of a Quadrant of a Circle (Risālah fī Qismah Rub‘ al-Dā’irah), undated but completed prior to the Treatise on Algebra,[11]: 831b [24]: § 2 and (iii) Treatise on Algebra (Risālah fi al-Jabr wa'l-Muqābala),[11]: 831b–832a [24]: § 3 most likely completed in 1079.[6]: 281 He furthermore wrote a treatise on the binomial theorem and extracting the nth root of natural numbers, which has been lost.[8]: 197 [11]: 832a [24]: § 4 [25]: 325b–326b

Theory of parallels

Part of Khayyam's Commentary on the Difficulties Concerning the Postulates of Euclid's Elements deals with the

Khayyam was the first to consider the three distinct cases of acute, obtuse, and right angle for the summit angles of a Khayyam-Saccheri quadrilateral.[6]: 283 After proving a number of theorems about them, he showed that Postulate V follows from the right angle hypothesis, and refuted the obtuse and acute cases as self-contradictory.[28]: 270 [29]: 133 His elaborate attempt to prove the parallel postulate was significant for the further development of geometry, as it clearly shows the possibility of non-Euclidean geometries. The hypotheses of acute, obtuse, and right angles are now known to lead respectively to the non-Euclidean hyperbolic geometry of Gauss-Bolyai-Lobachevsky, to that of Riemannian geometry, and to Euclidean geometry.[30]

Real number concept

This treatise on Euclid contains another contribution dealing with the theory of proportions and with the compounding of ratios. Khayyam discusses the relationship between the concept of ratio and the concept of number and explicitly raises various theoretical difficulties. In particular, he contributes to the theoretical study of the concept of irrational number.[32] Displeased with Euclid's definition of equal ratios, he redefined the concept of a number by the use of a continuous fraction as the means of expressing a ratio. Youschkevitch and Rosenfeld argue that "by placing irrational quantities and numbers on the same operational scale, [Khayyam] began a true revolution in the doctrine of number."[25]: 327b Likewise, it was noted by D. J. Struik that Omar was "on the road to that extension of the number concept which leads to the notion of the real number."[6]: 284

Geometric algebra

Rashed and Vahabzadeh (2000) have argued that because of his thoroughgoing geometrical approach to algebraic equations, Khayyam can be considered the precursor of

Solution of cubic equations

Khayyam seems to have been the first to conceive a general theory of cubic equations,

Khayyam produced an exhaustive list of all possible equations involving lines, squares, and cubes.

Whoever thinks algebra is a trick in obtaining unknowns has thought it in vain. No attention should be paid to the fact that algebra and geometry are different in appearance. Algebras are geometric facts which are proved by propositions five and six of Book two of Elements.

—Omar Khayyam[40]

In effect, Khayyam's work is an effort to unify algebra and geometry.[41]: 241 This particular geometric solution of cubic equations has been further investigated by M. Hachtroudi and extended to solving fourth-degree equations.[42] Although similar methods had appeared sporadically since Menaechmus, and further developed by the 10th-century mathematician Abu al-Jud,[43]: 29 [44]: 110 Khayyam's work can be considered the first systematic study and the first exact method of solving cubic equations.[45]: 92 The mathematician Woepcke (1851) who offered translations of Khayyam's algebra into French praised him for his "power of generalization and his rigorously systematic procedure."[46]: 10

Binomial theorem and extraction of roots

From the Indians one has methods for obtaining square and cube roots, methods based on knowledge of individual cases – namely the knowledge of the squares of the nine digits 12, 22, 32 (etc.) and their respective products, i.e. 2 × 3 etc. We have written a treatise on the proof of the validity of those methods and that they satisfy the conditions. In addition we have increased their types, namely in the form of the determination of the fourth, fifth, sixth roots up to any desired degree. No one preceded us in this and those proofs are purely arithmetic, founded on the arithmetic of The Elements.

—Omar Khayyam, Treatise on Algebra[47]

In his algebraic treatise, Khayyam alludes to a book he had written on the extraction of the th root of the numbers using a law he had discovered which did not depend on geometric figures.[39] This book was most likely titled the Difficulties of Arithmetic (Mushkilāt al-Ḥisāb),[11]: 832a [24]: § 4 and is not extant.[25]: 325b Based on the context, some historians of mathematics such as D. J. Struik, believe that Omar must have known the formula for the expansion of the binomial , where n is a positive integer.[6]: 282 The case of power 2 is explicitly stated in Euclid's elements and the case of at most power 3 had been established by Indian mathematicians. Khayyam was the mathematician who noticed the importance of a general binomial theorem. The argument supporting the claim that Khayyam had a general binomial theorem is based on his ability to extract roots.[48] One of Khayyam's predecessors, al-Karaji, had already discovered the triangular arrangement of the coefficients of binomial expansions that Europeans later came to know as Pascal's triangle;[49]: 60 Khayyam popularized this triangular array in Iran, so that it is now known as Omar Khayyam's triangle.[39]

Astronomy

In 1074–5, Omar Khayyam was commissioned by Sultan Malik-Shah to build an

The Jalālī calendar was a true

One of his pupils

Other works

He has a short treatise devoted to Archimedes' principle (in full title, On the Deception of Knowing the Two Quantities of Gold and Silver in a Compound Made of the Two). For a compound of gold adulterated with silver, he describes a method to measure more exactly the weight per capacity of each element. It involves weighing the compound both in air and in water, since weights are easier to measure exactly than volumes. By repeating the same with both gold and silver one finds exactly how much heavier than water gold, silver and the compound were. This treatise was extensively examined by Eilhard Wiedemann who believed that Khayyam's solution was more accurate and sophisticated than that of Khazini and Al-Nayrizi who also dealt with the subject elsewhere.[8]: 198

Another short treatise is concerned with

Poetry

The earliest allusion to Omar Khayyam's poetry is from the historian

There are occasional quotes of verses attributed to Khayyam in texts attributed to authors of the 13th and 14th centuries, but these are of doubtful authenticity, so that skeptical scholars point out that the entire tradition may be

Five of the quatrains later attributed to Omar Khayyam are found as early as 30 years after his death, quoted in

In addition to the Persian quatrains, there are twenty-five Arabic poems attributed to Khayyam which are attested by historians such as al-Isfahani, Shahrazuri (Nuzhat al-Arwah, c. 1201–1211), Qifti (Tārikh al-hukamā, 1255), and Hamdallah Mustawfi (Tarikh-i guzida, 1339).[8]: 39

The poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam has contributed greatly to his popular fame in the modern period as a direct result of the extreme popularity of the translation of such verses into English by Edward FitzGerald (1859). FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam contains loose translations of quatrains from the Bodleian manuscript. It enjoyed such success in the fin de siècle period that a bibliography compiled in 1929 listed more than 300 separate editions,[58] and many more have been published since.[57]:312

Philosophy

Khayyam considered himself intellectually to be a student of Avicenna.[2]: 474 According to Al-Bayhaqi, he was reading the metaphysics in Avicenna's the Book of Healing before he died.[7]: 661 There are six philosophical papers believed to have been written by Khayyam. One of them, On existence (Fi’l-wujūd), was written originally in Persian and deals with the subject of existence and its relationship to universals. Another paper, titled The necessity of contradiction in the world, determinism and subsistence (Darurat al-tadād fi’l-‘ālam wa’l-jabr wa’l-baqā’), is written in Arabic and deals with free will and determinism.[2]: 475 The titles of his other works are On being and necessity (Risālah fī’l-kawn wa’l-taklīf), The Treatise on Transcendence in Existence (al-Risālah al-ulā fi’l-wujūd), On the knowledge of the universal principles of existence (Risālah dar ‘ilm kulliyāt-i wujūd), and Abridgement concerning natural phenomena (Mukhtasar fi’l-Tabi‘iyyāt).

Khayyam himself once said:[59]: 431

We are the victims of an age when men of science are discredited, and only a few remain who are capable of engaging in scientific research. Our philosophers spend all their time in mixing true with false and are interested in nothing but outward show; such little learning as they have they extend on material ends. When they see a man sincere and unremitting in his search for the truth, one who will have nothing to do with falsehood and pretence, they mock and despise him.

Religious views

A literal reading of Khayyam's quatrains leads to the interpretation of his philosophic attitude toward life as a combination of

Al-Qifti (c. 1172–1248) appears to confirm this view of Khayyam's philosophy.[7]: 663 In his work The History of Learned Men he reports that Khayyam's poems were only outwardly in the Sufi style, but were written with an anti-religious agenda.[61]: 365 He also mentions that he was at one point indicted for impiety, but went on a pilgrimage to prove he was pious.[8]: 29 The report has it that upon returning to his native city he concealed his deepest convictions and practised a strictly religious life, going morning and evening to the place of worship.[61]: 355 Khayyam on the Koran (quote 84):[70]

The Koran! well, come put me to the test, Lovely old book in hideous error drest, Believe me, I can quote the Koran too, The unbeliever knows his Koran best. And do you think that unto such as you, A maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crew, God gave the Secret, and denied it me? Well, well, what matters it! believe that too.

Look not above, there is no answer there; Pray not, for no one listens to your prayer; Near is as near to God as any Far, And Here is just the same deceit as There.[70]

Men talk of heaven,—there is no heaven but here; Men talk of hell,—there is no hell but here; Men of hereafters talk, and future lives, O love, there is no other life—but here.[70]

An account of him, written in the thirteenth century, shows him as "versed in all the wisdom of the Greeks," and as wont to insist on the necessity of studying science on Greek lines. Of his prose works, two, which were stand authority, dealt respectively with precious stones and climatology. Beyond question the poet-astronomer was undevout; and his astronomy doubtless helped to make him so. One contemporary writes: "I did not observe that he had any great belief in astrological predictions; nor have I seen or heard of any of the great (scientists) who had such belief. He gave his adherence to no religious sect. Agnosticism, not faith, is the keynote of his works. Among the sects he saw everywhere strife and hatred in which he could have no part...."[71]: 263, vol. 1

Persian novelist Sadegh Hedayat says Khayyám from "his youth to his death remained a materialist, pessimist, agnostic. Khayyam looked at all religions questions with a skeptical eye", continues Hedayat, "and hated the fanaticism, narrow-mindedness, and the spirit of vengeance of the mullas, the so-called religious scholars."[72]: 13

In the context of a piece entitled On the Knowledge of the Principles of Existence, Khayyam endorses the Sufi path.[8]: 8 Csillik suggests the possibility that Omar Khayyam could see in Sufism an ally against orthodox religiosity.[73]: 75 Other commentators do not accept that Khayyam's poetry has an anti-religious agenda and interpret his references to wine and drunkenness in the conventional metaphorical sense common in Sufism. The French translator J. B. Nicolas held that Khayyam's constant exhortations to drink wine should not be taken literally, but should be regarded rather in the light of Sufi thought where rapturous intoxication by "wine" is to be understood as a metaphor for the enlightened state or divine rapture of baqaa.[74] The view of Omar Khayyam as a Sufi was defended by Bjerregaard,[75]: 3 Idries Shah,[76]: 165–166 and Dougan who attributes the reputation of hedonism to the failings of FitzGerald's translation, arguing that Khayyam's poetry is to be understood as "deeply esoteric".[77] On the other hand, Iranian experts such as Mohammad Ali Foroughi and Mojtaba Minovi rejected the hypothesis that Omar Khayyam was a Sufi.[63]: 72 Foroughi stated that Khayyam's ideas may have been consistent with that of Sufis at times but there is no evidence that he was formally a Sufi. Aminrazavi states that "Sufi interpretation of Khayyam is possible only by reading into his Rubāʿīyyāt extensively and by stretching the content to fit the classical Sufi doctrine.".[8]: 128 Furthermore, Boyle emphasizes that Khayyam was intensely disliked by a number of celebrated Sufi mystics who belonged to the same century. This includes Shams Tabrizi (spiritual guide of Rumi),[8]: 58 Najm al-Din Daya who described Omar Khayyam as "an unhappy philosopher, atheist, and materialist",[63]: 71 and Attar who regarded him not as a fellow-mystic but a free-thinking scientist who awaited punishments hereafter.[7]: 663–664

On the basis of all the existing textual and biographical evidence, the question remains somewhat open,[8]: 11 and as a result Khayyam has received sharply conflicting appreciations and criticisms.[61]: 350

Reception

The various biographical extracts referring to Omar Khayyam describe him as unequalled in scientific knowledge and achievement during his time.

FitzGerald's translation was a factor in rekindling interest in Khayyam as a poet even in his native Iran.

FitzGerald rendered Khayyam's name as "Tentmaker", and the anglicized name of "Omar the Tentmaker" resonated in English-speaking popular culture for a while. Thus, Nathan Haskell Dole published a novel called Omar, the Tentmaker: A Romance of Old Persia in 1898. Omar the Tentmaker of Naishapur is a historical novel by John Smith Clarke, published in 1910. "Omar the Tentmaker" is also the title of a 1914 play by Richard Walton Tully in an oriental setting, adapted as a silent film in 1922. US General Omar Bradley was given the nickname "Omar the Tent-Maker" in World War II.[86]: 13

The Moving Finger quatrain

The quatrain by Omar Khayyam known as "The Moving Finger", in the form of its translation by the English poet Edward Fitzgerald is one of the most popular quatrains in the Anglosphere.[87] It reads:

The Moving Finger writes; and having writ,

Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

The title of the novel "The Moving Finger" written by Agatha Christie and published in 1942 was inspired by this quatrain of the translation of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by Edward Fitzgerald.[87] Martin Luther King also cites this quatrain of Omar Khayyam in one of his speeches, "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence":[87][89]

“We may cry out desperately for time to pause in her passage, but time is adamant to every plea and rushes on. Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words, ‘Too late.’ There is an invisible book of life that faithfully records our vigilance or our neglect. Omar Khayyam is right: ‘The moving finger writes, and having writ moves on.’”

In one of his apologetic speeches about the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal, Bill Clinton, the 42nd president of the US, also cites this quatrain.[87][90]

Other popular culture references

In 1934 Harold Lamb published a historical novel Omar Khayyam. The French-Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf based the first half of his historical fiction novel Samarkand on Khayyam's life and the creation of his Rubaiyat. The sculptor Eduardo Chillida produced four massive iron pieces titled Mesa de Omar Khayyam (Omar Khayyam's Table) in the 1980s.[91][92]

The

Google has released two Google Doodles commemorating him. The first was on his 964th birthday on 18 May 2012. The second was on his 971st birthday on 18 May 2019.[94]

Gallery

-

"A Ruby kindles in the vine", illustration for FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by Adelaide Hanscom Leeson (c. 1905).

-

"At the Tomb of Omar Khayyam" by Jay Hambidge (1911).

-

The statue of Khayyam inPersian Scholars Pavilion donated by Iran.

-

Statue of Omar Khayyam in Bucharest

-

Monument to Omar Khayyam in Ciudad Universitaria of Madrid

See also

Notable films

Noted Khayyamologists

Notes

- ^ [oˈmæɾ xæjˈjɒːm]; /kaɪˈjɑːm, kaɪˈjæm/

- ^ With an error of one day accumulating over 5,000 years, it was more precise than the Gregorian calendar of 1582, which has an error of one day every 3,330 years.[8]: 200

- : 435

- ^ In e.g., al-Qifti,[8]: 55 or Bayhaqi.[16]: 463 [17]: 172–175, no. 66

- ^ Katz (1998), p. 270. Excerpt: In some sense, his treatment was better than Ibn al-Haytham's because he explicitly formulated a new postulate to replace Euclid's rather than have the latter hidden in a new definition.

- ^ O'Connor & Robertson (July 1999): However, Khayyam himself seems to have been the first to conceive a general theory of cubic equations.

- al-Isfahani.[8]: 49

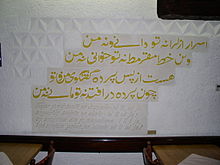

- ^ بر لوح نشان بودنیها بودهست — پیوسته قلم ز نیک و بد فرسودهست — در روز ازل هر آنچه بایست بداد — غم خوردن و کوشیدن ما بیهودهست

References

- ^ a b c d Tikkanen, Amy (28 February 2023). "Omar Khayyam: Persian poet and astronomer". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84511-541-8.

- ^ Dehkhoda, A.A. "Khayyam". Lūght-nāmah (in Persian). Tehran.

- ISBN 978-0-203-83301-8.

- ^ a b c O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (July 1999), "Omar Khayyam", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ JSTOR 27955652.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85168-355-0.

- ISBN 978-0-415-42600-8.

Omar composed his shafts of wit and shapes of beauty in his native Persian, which by the tenth century had recovered from the stunning blow dealt it by Arabic.

- ISBN 978-0-14-196501-7.in the tenth/eleventh century took it further by considering cubic and quartic equations, followed by the Persian mathematician and poet Omar Khayyam in the eleventh century.

Later, al-Karkhi (correct: al-Karaji), Ibn Tahir and the great Ibn al-Haytham

- ^ ISBN 90-04-07026-5.

- ^ Peter Avery and John Heath-Stubbs, The Ruba'iyat of Omar Khayyam, (Penguin Group, 1981), 14; "These dates, 1048–1031, tell us that Khayyam lived when the Seljuq Turkish Sultans were extending and consolidating their power over Persia and when the effects of this power were particularly felt in Nishapur, Khayyam's birthplace."

- S2CID 163490581.

- S2CID 246638673.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 177947195.

- ^ JSTOR 301524.

- ^ S2CID 143678233.

- ^ a b Edward FitzGerald, Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Ed. Christopher Decker, (University of Virginia Press, 1997), xv; "The Seljuq Turks had invaded the province of Khorasan in the 1030s, and the city of Nishapur surrendered to them voluntarily in 1038. Thus Omar Khayyam grew to maturity during the first of the several alien dynasties that would rule Iran until the twentieth century".

- ISBN 978-94-007-7747-7.

- S2CID 162241136.

- ^ ISBN 983-52-0157-9.

- ^ Lamb, Evelyn (28 October 2014). "In Which Omar Khayyam Is Grumpy with Euclid". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vahabzadeh, Bijan (7 May 2014). Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). "Khayyam, Omar xv. As Mathematician". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ ISBN 0-684-16962-2.

- hdl:10355/74778.

- ISSN 0172-570X.

- ^ ISBN 0-321-01618-1.

- ISBN 0-415-02063-8.

- JSTOR 27958258.

- OCLC 14156259.

- ^ Vahabzadeh, Bijan (2005). Jafar Aghayani-Chawoshi (ed.). "Omar Khayyam and the Concept of Irrational Numbers". Farhang: Quarterly Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies. Issue Topic: Commemoration of Khayyam (3). XVIII (53–54): 125–134.

- ^ JSTOR 3217882.

- JSTOR 27955653.

- S2CID 125245433

- S2CID 121468528.

- ^ Oaks, Jeffrey A. (2011). "Khayyām's Scientific Revision of Algebra" (PDF). Suhayl: International Journal for the History of the Exact and Natural Sciences in Islamic Civilisation. X: 47–75.

- ^ S2CID 124153443.

- ^ JSTOR 27957296.

- ^ Amir-Moez, A.R. (1963). "A Paper of Omar Khayyam". Scripta Mathematica. XXVI: 323–337.

- JSTOR 27951448.

- JSTOR 2688197.of Khayyam's method to degree four equations.

This paper contains an extension by Mohsen Hashtroodi

- ISBN 978-3-642-51599-6.

- ISBN 978-3-642-36736-6.

- ISBN 978-0-387-33060-0.

- ^ a b c Whinfield, E.H. (2000). The Quatrains of Omar Khayyam: The Persian Text with an English Verse Translation. New York: Psychology Press Ltd.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, E.F. (2006). "Muslim Extraction of Roots". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- JSTOR 2305028.

- ^ Nichols, Susan (2017). Al-Karaji: Tenth-Century Mathematician and Engineer. New York: Rosen Publishing.

- arXiv:1111.4926v2 [physics.hist-ph].

- Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- .

- arXiv:astro-ph/0409620v2.

- JSTOR 4311451.

- ^ a b c Ali Dashti (translated by L. P. Elwell-Sutton), In Search of Omar Khayyam, Routledge Library Editions: Iran (2012)

- ^ S2CID 246638673.

- ^ ISBN 9780947593476.

- ^ Ambrose George Potter, A Bibliography of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1929).

- ISBN 9780787637316.

- JSTOR 24881234.

- ^ S2CID 162611227.

- ^ Aminrazavi, M.; Van Brummelen, G. (Spring 2017). "Umar Khayyam". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ JSTOR 4300485.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ FitzGerald, E. (2010). Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (p. 12). Champaign, Ill.: Project Gutenberg

- ^ Schenker, D. (1981). "Fugitive Articulation: An Introduction to The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam". Victorian Poetry. XIX (1): 49–64.

- ^ Hedayat's "Blind Owl" as a Western Novel. Princeton Legacy Library: Michael Beard

- ^ Katouzian, H. (1991). Sadeq Hedayat: The life and literature of an Iranian writer. London: I.B. Tauris

- ^ Hitchens, C. (2007). The portable atheist: Essential readings for the nonbeliever. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo.

- ^ ISBN 9781773132372.

- ^ Robertson, J.M. (2016). A Short History of Freethough: Ancient and Modern.

- ISBN 9782714304896.

- JSTOR 23682646.

- S2CID 170388817.

- ^ Bjerregaard, C.H.A. (1915). Omar Khayyam, FitzGerald, Edward, 1809-1883, Sufism. London: Sufi Publishing Society.

- ^ Idries Shah, The Sufis, Octagon Press (1999)

- ISBN 0-473-01064-X

- ISBN 0-7914-6799-6.

- JSTOR 25210170.

- ^ J. D. Yohannan, Persian Poetry in England and America, 1977.

- ISBN 978-94-0060-079-9.

- ^ Simidchieva, M. (2011). FitzGerald's Rubáiyát and Agnosticism. In A. Poole, C. Van Ruymbeke, & W. Martin (Eds.), FitzGerald's Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Popularity and Neglect. Anthem Press.

- ^ UNIS. "Monument to Be Inaugurated at the Vienna International Centre, 'Scholars Pavilion' donated to International Organizations in Vienna by Iran".

- ^ "Khayyam statue finally set up at University of Oklahoma". Tehran Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Martin, William H.; Mason, Sandra (15 July 2009). Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). "Khayyam, Omar xiii. Musical Works Based On The Rubaiyat". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ Jeffrey D. Lavoie, The Private Life of General Omar N. Bradley (2015)

- ^ a b c d Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. (13 April 2018). "The Moving Finger: Glimpses into the Life of a Persian Quatrain". Leiden Medievalists Blog. Universiteit Leiden. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ FitzGerald, Stanza LXXI, 4th ed.

- ^ "17. MLK Beyond Vietnam.pdf (hawaii.edu)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Quatrain 36". exploring khayyaam -US. 21 December 2006. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Omar Khayyam's Table II Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Omar Khayyam's Table III Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. 1979. p. 255. Retrieved 8 September 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ "How Omar Khayyam changed the way people measure time". The Independent. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

Further reading

- Biegstraaten, Jos (2008). "Omar Khayyam (Impact On Literature And Society In The West)". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 15. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation.

- ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- ISBN 978-94-010-3481-4.

- Turner, Howard R. (1997). Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-78149-0.

External links

- Works by or about Omar Khayyam at Internet Archive

- Works by Omar Khayyam at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hashemipour, Behnaz (2007). "Khayyām: Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm al-Khayyāmī al-Nīshāpūrī". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 627–8. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version.)

- Umar Khayyam, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The illustrated Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám at the Internet Archive