Sewall Wright

Sewall Wright | |

|---|---|

William Ernest Castle | |

| Other academic advisors | Wilhelmine Key |

Sewall Green Wright

Biography

Sewall Wright was born in

As a child, Wright helped his father and brother print and publish an early book of poems by his father's student Carl Sandburg. At the age of seven, in 1897, he wrote his first "book", entitled Wonders of Nature,[5] and he published his last paper in 1988:[9] he can be claimed, therefore, to be the scientist with the longest career of science writing. Wright's astonishing maturity at the age of seven may be judged from the following excerpt quoted in the obituary:[5]

Have you ever examined the gizzard of a fowl? The gizzard of a fowl is a deep red colar with blu at the top. First on the outside is a very thick muscle. Under this is a white and fleecy layer. Holding very tight to the other. I expect you know that chickens eat sand. The next two layers are rough and rumply. These layers hold the sand. They grind the food. One night when we had company we had chicken-pie. Our Aunt Polly cut open the gizzard, and in it we found a lot of grain, and some corn.

He was the oldest of three gifted brothers—the others being the

He died in Madison, Wisconsin, on March 3, 1988.

Family

Wright married Louise Lane Williams (1895–1975) in 1921.[19][20] They had three children: Richard, Robert, and Elizabeth.[21][22]

Sewall Wright worshipped as a Unitarian.[23][24]

Scientific achievements and credits

Population genetics

His papers on

Evolutionary theory

Wright's explanation for

Path analysis

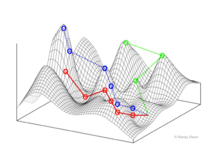

Wright's statistical method of path analysis,[4][36] which he invented in 1921 and which was one of the first methods using a graphical model, is still widely used in social science. He was a hugely influential reviewer of manuscripts,[1] as one of the most frequent reviewers for Genetics.

Plant and animal breeding

Wright strongly influenced

He did major work on the genetics of

Statistics

The creation of the statistical coefficient of determination has been attributed to Sewall Wright and was first published in 1921.[39] This metric is commonly employed to evaluate regression analyses in computational statistics and machine learning.

Wright and philosophy

Wright was one of the few geneticists of his time to venture into philosophy. He found a union of concept in Charles Hartshorne, who became a lifelong friend and philosophical collaborator. Wright endorsed a form of panpsychism. He believed that the birth of the consciousness was not due to a mysterious property of increasing complexity, but rather an inherent property, therefore implying these properties were in the most elementary particles.[40]

Legacy

Wright and Fisher, along with J.B.S. Haldane, were the key figures in the modern synthesis that brought genetics and evolution together. Their work was essential to the contributions of Dobzhansky, Mayr, Simpson, Julian Huxley, and Stebbins. The modern synthesis was the most important development in evolutionary biology after Darwin. Wright also had a major effect on the development of mammalian genetics and biochemical genetics.

Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie's The Book of Why (2018) describes the contribution of Wright's work on path analysis and delays in its acceptance by several technical disciplines (specifically statistics and formal causal analysis).[41]

Bibliography

- Wright, Sewall (1984). Evolution and the Genetics of Populations: Genetics and Biometric Foundations New Edition. University of Chicago Press.

- vol. 1, Genetic & Biometric Foundations. ISBN 0-226-91038-5

- vol. 2, Theory of Gene Frequencies. ISBN 0-226-91039-3

- vol. 3, Experimental Results and Evolutionary Deductions. ISBN 0-226-91040-7

- vol. 4, Variability within and Among Natural Populations. ISBN 0-226-91041-5

- vol. 1, Genetic & Biometric Foundations.

References

- ^ PMID 11616179.

- ^ a b Fowler, Glenn (March 4, 1988). "Sewall Wright, 98, Who Formed Mathematical Basis for Evolution". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Sewall Wright - American geneticist". britannica.com. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ PMID 2694927. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ PMID 3282168.

- PMID 3549442.

- PMID 8844140.

- ISBN 978-1-118-40857-5.. So were Darwin and his wife Emma (Wedgwood).

- ^ S2CID 85397524.

- PMID 5323812.

- PMID 15388764.

- ^ Lescouflair, Edric. "The Life of Sewall Wright". Harvard Square Library. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "Sewall Wright". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "Sewall Wright". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "American Mathematical Society". www.ams.org. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- MR 0006700.

- ^ "Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal". Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Ohio Marriages, 1800-1958," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XD4D-1CD : December 8, 2014), Sewall Wright and Louise Lane Williams, September 10, 1921; citing Licking, Ohio, reference 508B; FHL microfilm 384,312.

- ISBN 9780226684734. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

They were married in Granville on September 10, 1921... The Wrights had two boys, Richard and Robert, during the remaining four years in Washington.

- ^ "United States Census, 1930," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XSTH-NZW : accessed January 7, 2018), Sewall Wright, Chicago (Districts 0001-0250), Cook, Illinois, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 208, sheet 11A, line 50, family 226, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 423; FHL microfilm 2,340,158.

- ^ "Sewall Wright Profile".

- ISBN 9780674042995. Archived from the originalon January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

Wright worshipped as a Unitarian

- ISBN 9780226684734. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

Unitarian.

- S2CID 84048953.

- PMID 21009706.

- ^ PMID 18104586.

- .

- ^ The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (2002) by Stephen Jay Gould, Chapter 7, section "Synthesis as Hardening"

- S2CID 84667207.

- S2CID 85301374.

- S2CID 84400871.

- PMID 7297851.

- PMID 1763055.

- PMID 16577780.

- JSTOR 2527693.

- S2CID 84805740.

- PMID 13786823.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (January 1921). "Correlation and causation". Journal of Agricultural Research. 20: 557–585.

- S2CID 3255830.

- ISBN 978-0-465-09760-9.

Further reading

- Ghiselin, Michael T. (1997) Metaphysics and the Origin of Species. NY: SUNY Press.

- ISBN 978-0-226-68473-4.

- Wright, Sewall (1932). "The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution". Proc. 6th Int. Cong. Genet. 1: 356–366.

- Wright 1934, "The Method of Path Coefficients", Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 5: 161-215

- Wright, Sewall (1986). Evolution: Selected papers. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-91053-6 – via Internet Archive.

- Wright 1983, "Path Analysis in Genetic Epidemiology: A Critique"

External links

- Sewall Wright: Darwin's Successor—Evolutionary Theorist by Edric Lescouflair and James F. Crow

- Sewall Wright Papers at the American Philosophical Society

- Works by or about Sewall Wright at Internet Archive

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Sewall Wright", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews