Villard Houses

Villard Houses | |

New York City Landmark No. 0268–0270

| |

c. 1890 | |

| |

| Location | 29+1⁄2 50th Street, 24–26 East 51st Street, and 451–457 Madison Avenue, Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′29″N 73°58′31″W / 40.75806°N 73.97528°W |

| Built | 1882–84 |

| Architect | Joseph Morrill Wells of McKim, Mead & White |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| NRHP reference No. | 75001210[1] |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.004572 |

| NYCL No. | 0268–0270 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 2, 1975 |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980[2] |

| Designated NYCL | September 30, 1968 |

The Villard Houses are a set of former residences at 451–457

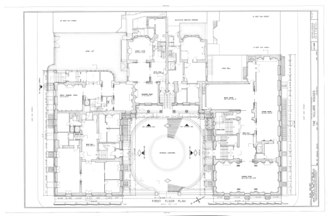

The building comprises six residences in a U-shaped plan, with wings to the north, east, and south surrounding a courtyard on Madison Avenue. The

The houses were commissioned by Henry Villard, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, shortly before he fell into bankruptcy. Ownership of the residences changed many times through the mid-20th century. By the late 1940s, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York had acquired all of the houses, except the northernmost residence at 457 Madison Avenue, which it acquired from Random House in 1971. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the complex as a city landmark in 1968, and the residences were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. As part of the New York Palace Hotel's development, completed in 1980, the north wing was turned into office space for the preservation group Municipal Art Society, which occupied the space until 2010.

Site

The Villard Houses are in the

Architecture

The Villard Houses complex was designed by Joseph M. Wells of the firm of McKim, Mead & White.[7][8] Charles Follen McKim of that firm was responsible for the overall plan, though Wells designed the individual details.[9][10] The homes are among several projects that McKim, Mead & White designed for railroad magnate Henry Villard.[11][12] The houses are designed in the Romanesque Revival style with Italian Renaissance touches;[10][13] they were the first major structures that McKim, Mead & White designed in the Italian Renaissance style.[13] At the time of the houses' construction, Wells had been encouraging the firm to use more classical architectural styles.[8]

The design was influenced by Rome's Palazzo della Cancelleria,[14][15][16][17] though some inspiration may have come from the Palazzo Farnese, also in Rome.[18][19] The two palazzos had been Wells's favorite Renaissance buildings.[10][14] The Palazzo della Farnesina has also been cited as an influence on the design of the Villard Houses.[19][8] The houses' design contained some major deviations from those of the Roman palazzos. For example, the Cancelleria's windows were decorated based on internal use, with the most elaborate windows at the piano nobile, while the Villard Houses' windows were decorated based on the floor height, with the most elaborate windows illuminating the guests' and servants' rooms on the top floors.[15] The houses were also partly influenced by the designs of German and Austrian multi-family buildings that Villard had seen in his youth.[20]

Layout and courtyard

The building was erected as six separate residences in a U-shaped plan,[21][a] with three wings surrounding a central courtyard on Madison Avenue.[23][22][24] At the time of the houses' completion, they faced a similar courtyard at the eastern end of St. Patrick's Cathedral.[24] The Lady Chapel at the cathedral had not yet been built, so St. Patrick's eastern end was a flat wall flanked by a rectory and an archbishop's house. The Villard courtyard was built to complement St. Patrick's courtyard, which was about the same size.[25]

The south wing consisted of a single residence, Henry Villard's residence at 451 Madison Avenue, also known as 291⁄2 East 50th Street.[3][25][26] The north wing consisted of three residences at 457 Madison Avenue (which occupied the western two-thirds of that wing) and 24–26 East 51st Street.[3][19] Both of these wings measure 60 feet (18 m) along Madison Avenue with a depth of 100 feet (30 m).[25][18] The eastern end of the south wing had a seven-story tower,[27] while the eastern end of the north wing had a 1+1⁄2-story entrance porch.[28][29] The center wing, on the east side of the courtyard, consisted of two residences at 453 and 455 Madison Avenue,[3] which extended 40 feet (12 m) eastward beyond the end of the north and south wings.[18]

The courtyard was designed both as a symbol of Villard's wealth and as an "urban gesture" to traffic on Madison Avenue.[16] The courtyard measures 80 feet (24 m) wide between the north and south wings and is 73 feet (22 m) deep.[18] It is flanked by two square posts with ball decorations above them. These posts are connected by a scrolled arch made of wrought iron.[28][30] A Florentine-style lamp is suspended from the wrought-iron arch.[28] Originally, the courtyard had a fountain surrounded by a circular driveway.[26] The driveway had been arranged to allow horse-drawn vehicles to enter the courtyard easily. The arrangement of residences around a courtyard was similar to the Apostolic Chancery at Vatican City.[31][32] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York used the courtyard as a parking lot during the mid-20th century. During the construction of the Palace Hotel in the 1970s, a marble and granite medallion was placed in the courtyard.[33]

Facade

The

The basement and first story of each house are rusticated.[39][40] The raised basement consists of rectangular openings, above which runs a molding with torus shapes. The first floor has arched windows, which are topped by spandrels with rosette-shaped medallions. The first floor is topped by an architrave with a plain frieze.[3] The ground story of the center wing at 453 and 455 Madison Avenue consists of five arches.[28][41][34] The center-wing arches are supported by granite columns.[18][42] There are decorative medallions above the arches.[25] Behind are the entrances to the center wing, as well as a barrel vault with rosette coffers and decorative moldings.[26][28]

The ground story of the north and south wings has doorways leading into the courtyard.

The upper stories are clad with plain stone ashlar.

Interior

McKim, Mead & White was involved in the original decoration of all the interiors,[14][45] and the firm's principals hired several friends to assist.[46] These included artistic-glass manufacturer John La Farge, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, painter Francis Lathrop, and mosaic artist David Maitland Armstrong.[45][47][48] Leon Marcotte, Sypher and Company, and A. H. Davenport and Company provided some of the furniture. Candace Wheeler may have designed some of the embroidered fabrics, and Ellin & Kitson performed much of the stone carving. Joseph Cabus designed a large portion of the houses' paneling, as suggested by his invoice for the building's woodwork, which was almost $100,000 (equivalent to $3,391,111 in 2023).[47]

All six residences' interiors were decorated with the highest-quality materials of the time.[15][45] As constructed, the residences had ornate furniture; for example, Villard's ground-story drawing room was upholstered with a reddish-brown color that harmonized with the color of the room.[18] The residences were built with 13 bathrooms, each of which contained terrazzo floors and tile and marble walls.[49] Each bedroom was fitted with its own bathroom.[18][26][50] The attic story of all of the residences was devoted to servants' rooms, storerooms, and other service facilities.[40] A portion of the mansion is available as an event rental within the New York Palace Hotel.[51]

Main residence

The most ornate detail was used in Villard's residence in the south wing.[48][52] His residence had four floors with several dozen rooms, whose designs were inspired by those of grand European houses.[53] Villard's ground story was the most elaborate, while the upper stories were less so.[18] Villard's residence had a billiard room, kitchen, servants' dining room, laundry, and wine room in the basement.[14][25][53]

Ground story

The ground, or first, story was designed in a similar style to a standard row house's parlor floor.[54] At ground level, there was a reception vestibule; a drawing-room suite divided into three sections; a music room with a balcony; and a dining room with a pantry.[18][25] These rooms were arranged enfilade, or on the same axis.[45]

Entering the south wing from the courtyard, visitors reached the Villard residence's reception vestibule. This vestibule had a set of marble steps and a wall with a tile mosaic band.

At the western end of the south wing's hallway was a drawing-room suite measuring 14 by 28 feet (4.3 by 8.5 m), flanked on either side by drawing rooms 19 by 28 feet (5.8 by 8.5 m).[18] Joseph Cabus designed wooden cabinetry for the space.[61] The drawing rooms had mahogany and white wood finishes, placed upon a light reddish-brown and yellow color scheme.[18][50] The family of Whitelaw Reid used these drawing rooms as a ballroom during the early 20th century,[62][63] with green marble columns and a gilded ceiling.[63] The drawing rooms also had ornate marquetry, which Reid subsequently reinstalled in his Purchase, New York, estate.[61] The Women's Military Services Club used the drawing rooms as a lounge in the 1940s.[64] After the opening of the New York Palace Hotel in 1980, it was turned into a cocktail room.[65][66][67]

The eastern end of the south wing's hallway contained a music room measuring 48 by 24 feet (14.6 by 7.3 m), with an elliptical vaulted ceiling 32 feet (9.8 m) high. A carved-pine wainscoting ran around the music room's wall at a height of 8 feet (2.4 m).[18] The music room was also known as the Gold Room because the decorations were colored gold.[28][68] A musicians' balcony was suspended on the north wall.[18][26][68] Musicians were able to enter the balcony via a staircase hidden behind the wall.[57][68][69] Saint-Gaudens installed five plaster casts on each of the north and south walls, which were copies of "singing angels" that Luca della Robbia designed for the Florence Cathedral.[61][70] John La Farge designed two lunettes called "Art" and "Music";[68][69] these were installed only after Reid moved into the house.[63] La Farge is also credited with designing leaded glass windows on the east wall, above the wainscot.[68][69] The decoration of the music room was finished only when Reid moved in.[59][63] It was turned into a cocktail lounge in 1980 but retained its original name.[66][67] Since 2019, the Gold Room has been a restaurant for the Lotte New York Palace Hotel.[69]

The southernmost portion of the ground story had a main breakfast room and a dining room that could be combined into a space measuring 20 by 60 feet (6.1 by 18.3 m).[18][59] The room had a wall with English oak and white mahogany, a ceiling with English oak beams, and carved friezes with floral designs. Two allegorical fireplace mantels, one at either end of the room, were made of red Verona marble and were carved by Saint-Gaudens.[50][56][71] One of the mantels was relocated several times before being installed in the Palace Hotel lobby in 1980.[33][71] The wall was divided into three sections by red-mahogany pilasters; the upper part of the wall had Villard monograms. An oak partition could be moved to divide the room into three segments.[26] The ceiling had paintings of mythological figures, which were designed by Francis Lathrop.[26][59][71] The dining room's cornice has inscriptions in Latin.[26][71][72] After Reid moved out, the dining room became a meeting room for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York.[72] In 1980, it became a bar within the hotel.[66][67]

Upper stories

The upper stories of number 451 had a floor layout similar to the ground story and also contained fireplaces.[26][50] The second-story hallway had a gilded ceiling, embossed-leather walls, and a large mantelpiece.[26] Adjoining the private music room was a private library fitted in mahogany with carved medallions on the bookcases. The coffered ceiling contained medallions of publishers and three murals.[50][73] The second-floor guest bedroom had gold and crimson decorations on the walls[26][50] and a ceiling with wooden cross beams.[50][74] A stairway with a wainscoted wall and a decorated balustrade led between the second and third stories of the south wing. The bedrooms on the third floor had chintz wall hangings and colorful decorations.[26] The Reid family largely retained these design details,[62] as did the Women's Military Services Club.[64]

Other residences

457 Madison Avenue, the Fahnestock residence in the north wing, had a reception hall and a ballroom, the latter of which was subdivided by

457 Madison Avenue had a gold-leaf ceiling and a circular stairway, designed by

History

Development

Planning

The houses were commissioned by Henry Villard, then the president of the Northern Pacific Railway.[11][12][80] Villard wanted a building that resembled palaces in his native Bavaria.[81] In April 1881,[44][82] he bought a plot on the east side of Madison Avenue between 50th and 51st streets from the trustees of St. Patrick's Cathedral.[17][83] The site was 200 feet (61 m) wide[82][17] and either 151 feet (46 m)[82] or 175 feet (53 m) deep.[17] At the time, what is now the Park Avenue railroad line ran in a trench directly behind the site, and Park Avenue itself was still known as Fourth Avenue.[19]

Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead & White was hired to design a group of houses for Villard,[80][83] arranged around a courtyard with a fountain and garden.[84] Villard had previously hired the firm to design other buildings;[53] in addition, McKim was one of Villard's family friends, and Villard's brother-in-law was married to McKim's sister.[17][44] The Real Estate Record and Guide speculated that the mansions were arranged to "secure privacy and get rid of tramps, and to live in a quiet and secluded way", similar to dwellings arranged around courtyards in the suburbs of London and Paris.[23][85] Villard planned to move into one of the houses and rent the remaining residences to his friends. The writer Elizabeth Hawes wrote that, by doing so, Villard wanted to create "a pleasant neighborhood unit" that positively impacted future urban developments.[21] A later New York Times article said that Villard had planned the entire complex as his own residence, but he was obligated to split it into multiple smaller units when his wealth declined.[62]

Details of the design were revised through October 1881, when McKim temporarily left New York City to work on a railroad terminal for Villard in Portland, Oregon.[83] Villard required that the houses be arranged around a courtyard to ensure residents' privacy, and he wanted to use brownstone rather than limestone or another material.[35] The job was reassigned to Stanford White, who, after a short time, left the city to visit his brother in New Mexico.[60][83] White then reassigned his projects to various junior architects in his office. Joseph M. Wells agreed to take over the design of the Villard Houses if the firm's remaining partner, William Rutherford Mead, allowed him to completely redesign the exterior. According to Leland Roth, one account had it that McKim and White had "immediately [became] advocates of Renaissance classicism" upon returning and seeing the updated plans.[83] Roth wrote that McKim and White were probably responsible for the general style of the facade,[83] although Wells was definitely responsible for the architectural details.[9][10][83] White's original architectural drawings for the project no longer exist.[60]

Early construction

By November 1881, excavation of existing buildings was underway at the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and 50th Street.

Villard obtained a mortgage loan for the property from the Manhattan Savings Institution in late 1882.[89][90] One of the three wings, likely Villard's own residence in the south wing, had been built by mid-1883.[91] McKim, Mead & White designed the interiors of all of the residences as well.[14][45] At the time, most residences were laid out by interior designers and decorators rather than architecture firms.[14] The interiors of each residence were designed to fit the tastes of the respective tenants.[14][92] Villard's residence itself cost $1 million without furnishing (equivalent to about $28.57 million in 2023), and the decoration cost another $250,000 (about $7.14 million in 2023).[18] Stanford White was proud of the project, recalling in 1896 that it was "the beginning of any good work that we may have done".[93] The residences were New York City's first houses designed in the Roman High Renaissance style and, at the time, differed significantly from the more ostentatious houses on Fifth Avenue nearby.[45]

Villard bankruptcy and completion

Villard fell into bankruptcy just before the houses were completed.[94][95] He moved into his mansion in December 1883, on the same day that he resigned from the Oregon and Transcontinental Company.[96] In late December 1883, Villard transferred two of the other lots next to his residence to his legal advisers, Edward D. Adams and Artemas H. Holmes.[89][15] According to Horace White, the transfers were made on the condition that Holmes and Adams construct residences similar in style to his own residence.[95] Adams lived at 455 Madison Avenue, while Holmes lived at 453 Madison Avenue.[23][76] The same month, Villard's own mansion was transferred to trustees William Crowninshield Endicott and Horace White to pay off a $300,000 debt.[97][98] The trustees oversaw the completion of the remaining houses around the courtyard.[14]

With the bankruptcy proceedings taking place, a crowd protested in the courtyard in early 1884, in the belief that all the houses around the yard belonged to Villard.[14][94][99] The Villard family moved out of the residence that May,[9] traveling to Dobbs Ferry, New York, after having lived on Madison Avenue for only a few weeks.[94] Work on the houses continued until 1885,[19] and Villard's finances had recovered by January 1886. William Endicott and Horace White were listed as having substantially completed the Villard Houses, which were transferred for a nominal sum to his wife, Fannie Garrison Villard.[100] The residence at 457 Madison Avenue was then sold to Harris C. Fahnestock,[89][15][101] who, along with Adams, was a banker with the firm Winslow, Lanier & Co.[100][102] Fahnestock had waited several months to obtain number 457, but the trustees refused to sell the property until all the other houses, besides Villard's residence, had been rented.[102] The rear residences on 24 and 26 East 51st Street were sold to other members of the Fahnestock family.[15]

The Villard residence itself was purchased in 1886 by Elisabeth Mills Reid, wife of New-York Tribune editor Whitelaw Reid.[22] The Reid family paid $400,000, half of what Villard had paid to build that house.[74][103] Stanford White redesigned the public rooms with decorations such as glass-and-onyx panels.[58] The residence at 24 East 51st Street was purchased by Scribner's Monthly publisher Roswell Smith in the late 1880s,[76] and Babb, Cook & Willard designed an expansion at number 24 in 1886.[29][76] The expansion, which was finished by 1892,[66] consisted of an L-shaped stairway leading to a double-arched entrance porch.[29]

Residential use

Roswell Smith died at 24 East 51st Street in 1892,[104] and his estate sold 24 and 26 East 51st Street two years later to Catherine L. and Charles W. Wells[105] for about $80,000.[106] Businessman E. H. Harriman was living in the north wing by 1899, when The New York Times reported on his involvement in the Harriman Alaska expedition.[107] In the first decades of the 20th century, many of the Villard Houses' residents remained in place, even when residential neighborhoods further uptown became more fashionable.[23] The Wells family continued to retain ownership of 24 East 51st Street until 1909, when the house was given to B. Crystal & Son as a partial payment for an apartment building in Washington Heights, Manhattan. At the time, the Reid, Holmes, Adams, and Fahnestock families still lived in the other residences.[108] Harris Fahnestock bought number 24 from B. Crystal & Son in 1910.[109] In that year's United States census, Fahnestock was recorded as living at number 457 with his grandson Snowden.[23]

Next door, the Reid family erected a seven- or eight-story addition east of number 451 in 1909.[41][76] The next year, McKim, Mead & White designed alterations to number 451, including new elevators.[110][111] By 1916, number 453 was leased to William Sloane.[112] At that point, the residences were known as Cathedral Court because they faced St. Patrick's Cathedral.[92][112] The following year, number 453 was in the process of being sold.[113][114] Elisabeth Reid acquired the house, loaning it during World War I to the American Red Cross.[115] Reid hired Raymond Hood in 1920 to make alterations to number 453.[116] The 1920 United States census recorded Reid as living at number 451 with seventeen servants.[23]

In March 1922, the estate of Mrs. Edward D. Adams sold the house at number 455. At this point, the southern half of the Villard Houses was owned by Reid and the north wing by Harris Fahnestock's children, William Fahnestock and Helen Campbell.[92] At that time, Charles Platt combined two of the units in the northern wing.[22][66] The Fahnestocks continued to live at number 457 until 1929.[31][32] Helen Campbell, who married John Hubbard in 1929,[117] intended to continue living at 24 East 51st Street for the rest of her life.[31][32] Helen's daughter, also named Helen, lived at number 455 with her husband Clarence Gaylor Michalis and their children.[118] In 1932, William Fahnestock financed his portion of the property with a $130,000 mortgage from the First National Bank.[119] The next year, John Hubbard died at number 24.[120][121] Meanwhile, following Reid's 1931 death,[122] the furnishings in number 451 were sold during a several-day-long auction in May 1934. The auction drew thousands of people to the Reid residence.[123][124]

Commercial conversion and preservation

1940s to 1960s

The Reid family lent number 451 to the Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies in March 1942.[125] The following May, the Women's Military Services Club opened its clubhouse in the interior of number 451,[126] and the French Relief Societies moved across the courtyard to number 457.[127][128] At the opening of the Military Services Club, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia declared, "You won't see any more private mansions like this. You'll see more wholesome houses for more people."[129][130] Robert J. Marony acquired number 457 for around $200,000 in June 1944.[31] The government of the United States had to approve the sale because three Fahnestock heirs were overseas in internment camps during World War II.[31][32] The title to number 457 was transferred to Joseph P. Kennedy, former U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, in April 1945. The transaction also showed that Kennedy obtained a 9⁄24 interest at 453–455 Madison Avenue.[131] Kennedy ended up never living there,[132] and it continued to be occupied by the French Relief Societies.[66] There was also an unsuccessful plan to place the temporary headquarters of the United Nations in the Villard Houses.[133]

The Women's Military Services Club closed in January 1946 after the end of World War II, having served 200,000 people.[134] Number 457, as well as a one-third interest in the courtyard, was acquired the same year by the publishing company Random House, which renovated the residence into its own offices.[135][136] Random House's publisher, Bennett Cerf, bought the house for $450,000, believing that to be the price Kennedy had paid.[75] The Archdiocese of New York purchased the houses at 451 and 453 Madison Avenue and 29 East 50th Street in October 1948 for an unknown amount in cash. The residences, which had been vacant for three years, had an assessed value of $825,000. The archdiocese needed space for its various agencies near St. Patrick's Cathedral, and the agencies' old headquarters had been sold to make way for the office structure at 488 Madison Avenue.[137][138] The archdiocese also purchased 455 Madison Avenue and 24 and 30 East 51st Street, as well as the vacant lot at 26–28 East 51st Street, in January 1949; these properties were valued at $600,000.[139][140] Francis Cardinal Spellman dedicated the archdiocese's offices at 451 and 453 Madison Avenue that May.[141][142]

The archdiocese hired

By the late 1960s, Random House owned number 457, and the Archdiocese of New York owned all of the other houses.[146] Random House initially intended to keep its space at 457 Madison Avenue, but ultimately leased space at an under-construction skyscraper at 825 Third Avenue in 1967.[147] At the time, Cerf called the residence "too valuable to keep".[75][133] By then, there were rumors that developers wanted to raze the houses and replace them with a skyscraper. The late Cardinal Spellman's successor, Terence Cardinal Cooke, had not made a public statement about the houses,[148] but Monsignor James Rigney said: "At some point we would have to wonder whether we are justified in keeping property as valuable as this."[75][149] On September 30, 1968,[150] the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the complex as official landmarks, preventing them from being modified without the LPC's permission.[146][151]

1970s

In 1970, Richard Ottinger leased the old Random House mansion for his U.S. Senate campaign's offices.[152] Architectural writer Ada Louise Huxtable said the entire complex was in danger of being redeveloped if the archdiocese were to gain control of the Random House residence and thus full control of the land.[153] After the archdiocese received $2.25 million from Gillette CEO Henry Jacques Gaisman, it purchased number 457 in early 1971.[132][154] According to the archdiocese's real estate adviser, John J. Reynolds, the archdiocese wanted to preserve the houses so there would be open space in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral.[132] Later in 1971, the archdiocese announced it would move to 1011 First Avenue by the following year and would lease out the Villard Houses.[155][156] When the new archdiocesan headquarters opened in November 1973, the archdiocese said it hoped to find a lessee for the Villard Houses rather than sell them.[157]

In early 1974, the archdiocese was negotiating with developer Harry Helmsley to sell him the air rights above the Villard Houses.[129][158] Helmsley planned to build a 50-story hotel tower next to or above the houses.[66][129] By late 1974, the archdiocese had leased the Villard Houses to Helmsley for 99 years at around $1 million per year.[159] An early plan for the hotel called for demolishing the rear of the houses and gutting much of the interior,[52][160] including the Gold Room.[52][161] Following objections, Helmsley presented a modified plan in June 1975, which still called for demolishing part of the rear and interior.[162][163] The houses were placed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 2, 1975,[1] which prevented federal funds from being used to demolish any part of the houses unless the federal government approved it.[164] The same month, Helmsley presented a modified proposal that preserved the Gold Room.[33][52][164]

The archdiocese hired William Shopsin in January 1976 to conduct a historical survey of the Villard Houses.

A groundbreaking ceremony for the hotel occurred on January 25, 1978.[170][171] The decorative interiors of the Villard Houses were placed into temporary storage,[168][172][173] and the hotel's developer took precautions to avoid damaging the houses.[165][174] Interior designer Sarah Lee was largely responsible for the redesign of the interior spaces.[33][67] The Gold Room was renovated and turned into a cocktail lounge, while the old library was refurbished with 4,000 false books.[72] The old drawing room of the south wing was redesigned as a cocktail lounge as well, while the old dining room became the hotel's Hunt Bar.[67] The facade and courtyard were also restored,[175] though the easternmost section of the complex, including much of the central wing and the additions on 50th and 51st streets, was demolished.[33][52] The project even involved replacing some city streetlights outside the Villard Houses.[52] One of the houses' roofs was damaged in October 1979 when a heavy object fell through it.[176]

Later use

Helmsley leased 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) in the Villard House's north wing to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in June 1979.[177] The space was to contain the Urban Center, the headquarters of four civic organizations: the American Institute of Architects, the Architectural League of New York, the Municipal Art Society (MAS), and the Parks Council of New York.[178] Two months later, Capital Cities Communications leased space in the hotel tower.[179]

1980s and 1990s

James Stewart Polshek and Associates renovated the north wing of the Urban Center.[78][180] The carved cornice and parquet floors of the north wing were restored, but the reception rooms were repainted and lighted for the new tenants. The Urban Center's space opened in August 1980.[181] The hotel opened the next month.[182] An architecture bookstore run by MAS opened in the north wing in October 1980; the store's first exhibition was about the Villard Houses themselves.[183][184] The second floor was used for exhibitions, the third and fifth floors were used for organizations, and the first and fourth floors were rented as commercial space. The Urban Center's offices were rearranged from 1981 to 1982 because the original layout was inefficient.[78] The ground story of the south wing had a cocktail lounge in the former drawing room, a bar in the former dining room, and the Gold Room in the same place as before.[66] Fashion boutique Celine of Paris leased a 5,500-square-foot (510 m2) space in the north wing in 1981.[185] During the 1980s and 1990s, the fraudulent debt-collection agency Towers Financial Corporation had offices at the Villard Houses.[186][187]

In late 1993, the houses and the New York Palace Hotel were sold to the

2000s to present

The owners of the Palace Hotel renovated the brownstone facade for $300,000 in late 2003. At the time, James W. Rhodes estimated that 99 percent of the facade's original brownstone remained; some of the pieces for the restoration had come from the demolished rear portions of the houses.[23] The MAS held a discounted lease for the space in the north wing until 2006; when the discount expired, the organization had the option to pay market rates for another 24 years.[196] MAS paid $175,000 in rent annually at the time,[196][197] but it was already considering relocating.[196] The organization moved out of the Villard Houses in 2010.[198] The building stood vacant afterward, and the Palace Hotel's owners wanted to incorporate the Villard Houses into a portion of the hotel.[197]

In 2011, the hotel was sold to Northwood Investors, which extensively renovated the hotel and the Villard Houses.

Reception

At the time of the houses' completion, wealthy New Yorkers found the buildings' design to be restrained compared with other mansions.[45] The trade magazine Real Estate Record initially said there was "nothing indeed to indicate architecture except the delicacy of some of the detail".[91] By contrast, the British magazine The Architect said the Villard residence "will be the most magnificent residence building in the [United] States, far surpassing the Vanderbilt houses" along Fifth Avenue.[18] After the houses were complete, a critic for the Real Estate Record characterized the Villard Houses as "a mild success" and said that despite their large size and plain facade, the houses were "in no way offensive and can never come to look trivial or vulgar".[42] Another article for the same publication described the Villard residence in particular as "the only example of consistent adherence to one style" in New York City.[55] The New York Evening Post said the residences were unique among New York City residences and were a departure from the château-style residences elsewhere in the city.[23] The main residence was the subject of an 1897 handbook published by Edith Wharton.[94]

The Christian Science Monitor wrote in 1934 that the buildings retained "the same dignity that accompanied them in 1883" and that their construction had spurred the start of interior decoration.[9] Ada Louise Huxtable described the buildings in 1968 as "one of the best buildings New York could and can claim, then or now".[148] The New York Times reported in 1971, "The complex has long been regarded as one of New York City's architectural treasures."[132] Even so, the houses remained relatively nondescript through the late 20th century.[208] Harmon Goldstone and Martha Dalrymple wrote in a 1974 book: "It is a minor miracle that this magnificent architectural island still survives in the center of midtown Manhattan."[43] Architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern described the Villard Houses as McKim, Mead & White's "first scholarly essay in the Classical architecture of the Italian Renaissance".[209] Architectural historian Leland M. Roth described Villard's residence in particular as "a standard of restrained elegance in interior decoration".[94] Elizabeth Hawes said the houses helped to popularize the use of classical architectural styles in the city's residences.[210]

During the 1970s, when the Palace Hotel was being developed, preservationists fought strongly to keep the houses.[66] Huxtable had called Helmsley's 1974 proposal for the Palace hotel "a death-dealing rather than a life-giving 'solution'".[150][211] She had similarly criticized the June 1975 plan, saying: "By any measure except computerized investment design, the results are a wretched failure."[52][212] By contrast, when the September 1975 proposal called for saving the Gold Room, Huxtable stated: "There is now the promise of a solution that all can abide by."[213] Many preservationists were not completely content with the Palace Hotel's location, but Helmsley was nevertheless credited with saving the houses.[52] In 1981, the AIA Journal described the project as "a product of admirable human energy and down-to-earth compromise and [...] a much happier event than the architectural funeral most observers would have bet on six years ago".[214]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b "Federal Register: 44 Fed. Reg. 7107 (Feb. 6, 1979)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 6, 1979. p. 7538 (PDF p. 338). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Park Service 1975, p. 2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ "457 Madison Avenue, 10022". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "455 Madison Avenue, 10022". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, pp. 601–602.

- ^ a b c Hawes 1993, p. 86.

- ^ ProQuest 513594238.

- ^ a b c d Craven 2009, p. 243.

- ^ a b Roth 1983, p. 85.

- ^ a b Wilson 1983, p. 95.

- ^ a b Wilson 1983, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 602.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roth 1983, p. 88.

- ^ a b Wilson 1983, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Reynolds 1994, p. 235.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "A New York Palace". The Architect. Vol. 31. London. January 12, 1884. p. 34. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e AIA Journal 1981, p. 69.

- ^ Hawes 1993, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Hawes 1993, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 1975, p. 5.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1994, pp. 235–236.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reynolds 1994, p. 236.

- ^ ProQuest 357226446.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1968a; National Park Service 1975, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Park Service 1975, p. 3.

- ^ a b c "Henry Villard Houses (in part), 24–26 East 51st Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 30, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Henry Villard Houses (in part), 457 Madison Avenue" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 30, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1313612846.

- ^ from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h AIA Journal 1981, p. 71.

- ^ a b Craven 2009, p. 246.

- ^ a b Hawes 1993, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Hawes 1993, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Roth 1983, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Hawes 1993, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c The Architect 1884; National Park Service 1975, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Craven 2009, p. 245.

- ^ a b c d "Henry Villard Houses (in part), 451–455 Madison Avenue and 29 1/2 East 50th Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 30, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Some Up-Town Buildings". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 33, no. 825. January 5, 1884. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c White & White 2008, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hawes 1993, p. 90.

- ^ Wilson 1983, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Craven 2009, p. 247.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1994, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Waring, George E. Jr. (August 16, 1884). "The Drainage of the Villard House in New York". American Architect and Building News. Vol. 16. pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Real Estate Record 1885, p. 1248.

- ^ New York Palace. Archivedfrom the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1129.

- ^ a b c Hawes 1993, p. 88.

- ^ Hawes 1993, pp. 88–90.

- ^ a b c Real Estate Record 1885, p. 1247.

- ^ a b Wilson 1983, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Reynolds 1994, p. 237.

- ^ a b White & White 2008, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Craven 2009, p. 248.

- ^ a b c White & White 2008, p. 93.

- ^ a b c White & White 2008, p. 98.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d White & White 2008, p. 102.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i AIA Journal 1981, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e Architectural Record 1981, p. 68 (PDF p. 24).

- ^ a b c d e f Nonko, Emily (April 27, 2016). "Exclusive Photos: Tour the Lavish South Wing of the Gilded Age Villard Houses". 6sqft. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Tan, Michael (June 11, 2019). "Lotte New York Palace opens The Gold Room restaurant". Hotel Management. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Reynolds 1994, pp. 237–238.

- ^ a b c d Reynolds 1994, p. 238.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 1975, p. 4.

- ^ ProQuest 578805390.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1975, p. 7.

- from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c Wasserman, Joseph (August 1981). "The Program" (PDF). Oculus. Vol. 43. pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ AIA Journal 1981, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 28, no. 714. November 19, 1881. p. 1075. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Reynolds 1994, p. 234.

- ^ ProQuest 93903225.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roth 1983, p. 86.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 28, no. 717. December 10, 1881. p. 1145. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "The New York House of the Future". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 28, no. 720. December 31, 1881. p. 1208. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Plans Filed". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 29, no. 738. May 6, 1882. p. 470. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 87.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ProQuest 937975691.

- ^ a b "Millionaires' Houses". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 32, no. 801. July 21, 1883. p. 522. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 607.

- ^ a b c d e Roth 1983, p. 90.

- ^ ProQuest 494942002.

- ProQuest 940671015.

- (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ "The Northern Pacific: Resignation of President Villard". New-York Tribune. January 5, 1884. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Conveyances". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 33, no. 830. February 9, 1884. p. 139. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ ProQuest 573235338.

- ^ "Villard's Mansion Sold to Whitelaw Reid". Democrat and Chronicle. October 16, 1886. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ "Roswell Smith at Rest". The Evening World. April 21, 1892. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Sales of the Week". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 54, no. 1373. July 7, 1894. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Washington Heights Corner Exchanged". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 84, no. 2178. December 11, 1909. p. 1956. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Sale of One of the Villard Houses". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 85, no. 2196. April 16, 1910. pp. 826–827. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Manhattan Alterations". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 85, no. 2189. February 26, 1910. p. 436. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Manhattan". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 97, no. 2496. January 15, 1916. p. 107. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "North of 59th Street". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 99, no. 2553. February 17, 1917. p. 225. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ProQuest 98146106.

- ProQuest 576322159.

- ^ "Contemplated Construction". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 105, no. 23. June 12, 1920. p. 788. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ProQuest 1337004322.

- ProQuest 1222039256.

- ProQuest 1222120543.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ProQuest 1125472940.

- ProQuest 1267949104.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ProQuest 1268023939.

- ^ a b c Burke, Mack; Coen, Andrew (January 13, 2014). "From the Vault: New York Palace Hotel, 455 Madison Avenue". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1127.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ProQuest 1322158646.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ProQuest 1327438572.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ProQuest 1327119419.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ProQuest 1326840176.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1127–1128.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1128.

- ^ "Try to Save Villard Houses". New York Daily News. October 3, 1968. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "Church Buys A Landmark". New York Daily News. March 12, 1971. p. 30. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "Villard Houses To Be Leased". New York Daily News. August 12, 1971. p. 82. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Reel, William (November 9, 1973). "20 Stories & a New Chapter". New York Daily News. p. 30. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Dragadze, Peter (1980). "The House that Henry Built and Harry Topped". Town & Country. pp. 142, 144.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Swertlow, Eleanor (May 28, 1975). "Music Room Headed for Dirge?". New York Daily News. p. 112. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ AIA Journal 1981, pp. 70–71.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c Architectural Record 1981, p. 67 (PDF p. 23).

- ^ Mason, Bryant (October 22, 1976). "Estimate Board Approves New Hotel". New York Daily News. p. 107. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Architectural Record 1981, p. 65 (PDF p. 21).

- ProQuest 146895488.

- ^ "Into Glitter of Hotel Biz, Enter, The Palace". New York Daily News. January 26, 1978. p. 305. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ProQuest 134276172.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Yielding to Progress". New York Daily News. March 15, 1978. p. 327. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ProQuest 512130103.

- ^ "Outstanding architecture". The Journal News. November 11, 1979. p. 79. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "House-razing". New York Daily News. October 26, 1979. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Jackie's artsy gesture". New York Daily News. June 22, 1979. p. 266. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ AIA Journal 1981, p. 72.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Cherubin, Jan (October 4, 1980). "Sites of the city". New York Daily News. p. 269. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Ward, Vicky (June 27, 2011). "The Talented Mr. Epstein". Vanity Fair. New York City: Condé Nast. Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ProQuest 398466633.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- OL 22741487M.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Sulzberger, A. G. (January 14, 2010). "Urban Center Draws Its Curtains Closed". City Room. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Brandt, Nadja (May 18, 2011). "New York Palace Hotel to Be Sold to Kukral's Northwood". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ProQuest 1710724379. Archived(PDF) from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Classic Villard mansion clicks with new e-tailer". Real Estate Weekly. October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Lotte New York Palace Opens Restaurant in The Villard Mansion". Luxury Travel Magazine. August 31, 2016. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Fractenberg, Ben (March 1, 2017). "$100M Loan to Archdiocese May Not Cover All Abuse Victim Claims: Lawyer". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 601.

- ^ Hawes 1993, p. 91.

- ProQuest 120575764.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ AIA Journal 1981, p. 73.

Sources

- Craven, Wayne (2009). Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06754-5.

- Hawes, Elizabeth (1993). New York, New York: How the Apartment House Transformed the Life of the City (1869-1930). A Borzoi book. A.A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-55641-3.

- "Interior of the Villard House". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 36, no. 922. November 14, 1885. pp. 1247–1248 – via columbia.edu.

- Kathrens, Michael C. (2005). Great Houses of New York, 1880–1930. Acanthus Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-926494-34-3.

- "The Latest Life of the Villard Houses" (PDF). AIA Journal. Vol. 70, no. 2. February 1981. p. 271. ISSN 0001-1479.

- Reynolds, Donald (1994). The Architecture of New York City: Histories and Views of Important Structures, Sites, and Symbols. J. Wiley. OCLC 45730295.

- Roth, Leland (1983). McKim, Mead & White, Architects. Harper & Row. OCLC 9325269.

- Shopsin, William (1980). The Villard Houses: Life Story of a Landmark. New York: Viking Press. OCLC 6486604.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. OL 1130718M.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. Monacelli Press. OCLC 40698653.

- "The Villard Houses" (PDF). Architectural Record: Record Interiors. February 1981. pp. 65–68.

- "Villard Houses" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 2, 1975.

- White, Samuel G.; White, Elizabeth (2008). Stanford White, Architect. Rizzoli. OCLC 192080799.

- Wilson, Richard Guy (1983). McKim, Mead & White, architects. Rizzoli. OCLC 9413129.