Hudson Theatre

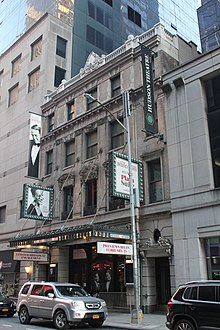

44th Street facade as seen in 2022 | |

| |

| Address | 141 West 44th Street Manhattan, New York City United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′25″N 73°59′05″W / 40.75694°N 73.98472°W |

| Owner | Millennium & Copthorne Hotels |

| Operator | Ambassador Theatre Group |

| Type | Broadway |

| Capacity | 970 |

| Production | Merrily We Roll Along |

| Construction | |

| Opened | October 19, 1903 |

| Reopened | February 8, 2017 |

| Years active | 1903–1934, 1937–1949, 1960–1968, 2017–present |

| Architect | J.B. McElfatrick & Son; Israels & Harder |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Designated | November 15, 2016[1] |

| Reference no. | 16000780 |

| Designated entity | Theater |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | November 17, 1987[2] |

| Reference no. | 1340[2] |

| Designated entity | Facade |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | November 17, 1987[3] |

| Reference no. | 1341[3] |

| Designated entity | Lobbies and auditorium interior |

The Hudson Theatre is a

The Hudson Theatre's

The Hudson was originally operated by Henry B. Harris, who died in the 1912 sinking of the Titanic. His widow, Renee Harris, continued to operate the Hudson until the Great Depression. It then served as a network radio studio for CBS from 1934 to 1937 and as an NBC television studio from 1949 to 1960. The Hudson operated intermittently as a Broadway theater until the 1960s and subsequently served as an adult film theater, a movie theater, and the Savoy nightclub. The Millennium Times Square New York hotel was built around the theater during the late 1980s, and the Hudson Theatre was converted into the hotel's event space. The Hudson Theatre reopened as a Broadway theater in 2017 and is operated by the Ambassador Theatre Group; the building is owned by Millennium & Copthorne Hotels.

Site

The Hudson Theatre is at 139–141 West 44th Street,[4][5] between Seventh Avenue and Sixth Avenue near Times Square, in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City.[6] It is between the two wings of the Millennium Times Square New York hotel,[4] of which the Hudson Theatre is technically part.[6] The primary elevation of the facade is along 44th Street; a rear elevation extends north to 45th Street.[7] The theater's land lot originally had the addresses 139 West 44th Street and 136–144 West 45th Street.[8][9] It had a frontage of 42.6 feet (13.0 m) on 44th Street and 83.4 feet (25.4 m) on 45th Street, with a depth of 200 feet (61 m) between the two streets.[10] The modern hotel's lot includes the theater. The lot covers 16,820 square feet (1,563 m2), with a frontage of 117.42 feet (35.79 m) on 44th Street and a depth of 200 feet (61 m).[6]

On the same block,

Design

The Hudson Theatre was designed in the Beaux-Arts style and constructed from 1902 to 1903.[4][12] The architectural firm J. B. McElfatrick & Son was the original architect, but the firm of Israels & Harder oversaw the completion of the design.[4][13] It is not known why the plans were changed.[13] McElfatrick was a prominent theater architect, but Charles Henry Israels and Julius F. Harder are not known to have designed any other theaters.[14] Plans indicate that McElfatrick designed the facade while Israels and Harder designed the interior.[14][15]

Facade

The Hudson Theatre's

44th Street

The first-story facade consists of rusticated blocks of limestone, with a water table made of granite.[18] The outermost bays contain wood-and-glass double doors, which are recessed deeply from the facade. Above each of the outer doorways are brackets supporting a cornice, which is topped by a bull's-eye window with cornucopias on either side.[17] The three inner bays contain the theater's main entrance, which is also recessed.[20] Within the main entrance opening are three sets of wood-and-glass double doors, above which is a wooden transom bar and glass window lights above. The central set of doors has a scroll frame, which is topped by a circular window flanked by oval window lights.[16] A marquee hangs above the inner bays and is supported by tie rods from the third story of the facade.[20] This marquee dates from 1990 but is similar in design to the original marquee.[16] A belt course with small dentils runs above the first floor.[20]

At the second and third stories, four double-height

The third-story windows all have limestone surrounds and double-hung sash windows.

The fourth-story windows are sash windows, similar to those on the third story, except that the three middle windows are flanked by

45th Street

The north elevation is plain in design and is made of tan brick in Flemish bond. The stage house, comprising most of the 45th Street elevation, is flanked by one-bay-wide, five-story-tall galleries. The base of the stage house contains three blind arches, with recessed openings in the two outer arches.[19] The western opening has a stage door. The imposts below the tops of the arches are connected to each other, creating a belt course above the second story.[23] The upper stories of the stage house are also divided into three bays by single and double pilasters. The capitals of these pilasters are topped by Corinthian capitals with mask decorations.[19] Recessed brick panels flank the outer bays.[23] Above the stage house is a metal cornice with a reeded frieze, modillions, and medallions.[19]

On either side of the stage house are the galleries. At the first story, there are metal emergency exit doors.[23] The upper stories have double-hung windows with cast stone lintels.[19] A wrought-iron fire escape runs in front of both galleries. The fifth-story windows contain cast-stone lintels, above which are arches and limestone cornices.[23]

Interior

The Hudson Theatre has multiple interior levels.[25] On 44th Street, the first story contains an entrance, ticket lobby, and main lobby. The second story (once the Dress Circle) was partitioned into offices after the original Broadway theater closed, while the third and fourth stories were divided into apartments. On 45th Street is the stage house, comprising the three-level auditorium, the stage, and backstage facilities. The lobbies and auditorium are ornately decorated in the Beaux-Arts Classical style, while the backstage facilities in the basement, rear, and sides of the theater are simply decorated.[25] The three lobby spaces collectively measure 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and 100 feet (30 m) long, wider than any other lobby in New York City when the theater opened in 1903.[26][27][28] The lobbies and auditorium contained several hundred concealed lamps, which could be dimmed and which comprised a diffused lighting system.[29]

Lobbies

Entrance vestibule

The rectangular entrance vestibule from 44th Street measures 36 feet (11 m) wide by 16 feet (4.9 m) deep.

Ticket lobby

The ticket lobby has a coved plaster ceiling with 264 coffers.[27][28][31] The coffers are separated by bands and originally contained mounts for incandescent light bulbs.[34][32] The light bulbs were removed and replaced with chandeliers at some point after the theater opened.[31][32] A 1903 news article compared the ticket lobby's ceiling and plaster decorations to the Roman Baths of Titus.[27][35]

Inner lobby

Four pairs of bronze-and-glass doors lead from the ticket lobby northward to the inner lobby,

The north wall has a red curtain separating the foyer from the auditorium.[31] Originally, this curtain was green and covered with gold trimming.[27] Wide, ornamented plaster bands divide the ceiling into three sections, each of which has a Tiffany stained-glass dome.[41] The domes contain gold, green, pink, and turquoise glass pieces, which date from their original installation.[32] The center dome has a chandelier, and ten shallow crystal lamps surround the domes. The ceiling's edges have coffers with three-part stained-glass panels.[40]

Auditorium

The auditorium has an orchestra level, boxes, two balconies, promenades on the three seating levels, and a large stage behind the proscenium arch. The auditorium's width is slightly greater than its depth, and the auditorium is designed with plaster decorations in high relief.[41] The balcony levels are connected by stairs on either side and by fire stairs outside the auditorium.[42] The auditorium was equipped with 28 emergency exits at its opening, more than in most contemporary venues at the time of its opening.[27][28][36] The floor had "mushrooms" for air intake and outflow.[28][29] Ventilation and heating could both be adjusted to accommodate outside conditions, and a sprinkler system was included in the original design.[29][36] While these mechanical features have since become standard building-design elements, they were not common at the time of the Hudson Theatre's construction.[29] There were originally 12 restroom stalls in the theater, which were expanded to 27 when the theater reopened in 2017.[43]

Seating areas

The Hudson Theatre was built with a capacity of 1,076 seats.[44] The modern auditorium has 970 seats.[45] Each seat is 23 inches (580 mm) wide, larger than typical Broadway seats, which typically measure only 17 inches (430 mm) wide.[32] The seats contain gold-colored cushions with wooden backs and were manufactured by Kirwin & Simpson.[15][32][46]

The foyer leads directly to a promenade that curves along the rear of the orchestra. The promenade's rear wall is paneled, while its ceiling contains bands and moldings that divide it into multiple sections.[47] Three tall columns separate the promenade from the orchestra seating.[42] The promenade formerly linked to a women's lounge, with large mirrors, east of the foyer. A marble-and-bronze staircase leads up from the west end of the orchestra promenade to the balconies.[28][40] A men's lounge existed under the western staircase;[28] it was subsequently converted into restrooms.[43] Similar promenades exist on either balcony level, separated from the seats in front by half-height partitions.[48] An elevator leads to the Dress Circle level, with steps down to the first balcony, but there is no elevator access to the second balcony.[49]

The balcony levels have paneled pilasters on their walls, ornamental moldings on their fronts, and foliate bands on their undersides.[50] In front of the balconies are yellow and gold moldings with Tiffany mosaic tiles.[42] Unlike other Broadway theaters of the 1900s, the balconies are largely cantilevered rather than being supported on columns.[28][51] According to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), the use of cantilevered balconies strongly suggested that Israels & Harder was responsible for the interior design,[51] since McElfatrick & Son used support columns even after cantilevered balconies were the norm.[14][52] At the rear of the first balcony, columns with Corinthian capitals support the second balcony.[50]

The orchestra has yellow side-walls with paneled pilasters.

Other design features

Next to the boxes is the proscenium arch, which consists of a wide, paneled band with a

The orchestra boxes' columns support a sounding board, which curves onto the ceiling above the proscenium arch. Foliate bands and moldings surround the sounding board, form a cove. The sounding board is divided into hexagonal panels with light sockets, though few light bulbs remain.[50] Behind the sounding board, the walls of the second balcony level curve to form the ceiling. There are wide plaster bands, containing moldings and octagonal panels; the moldings divide the ceiling into groined panels with neoclassical foliate decoration.[50] The rear of the ceiling contains plasterwork with light sockets, as well as glazed light bulbs.[42] According to one restoration architect, the pattern of the ceiling inspired a hexagonal motif for the restoration of the theater.[15]

Other facilities

The basement lies under the entire site and protrudes below 45th Street. Five staircases and one elevator connect the basement to the ground story, while two doors lead to the Millennium Times Square hotel's wings.

The second story on the 44th Street wing was once the Hudson Theatre Dress Circle. It was partitioned into offices after the theater originally closed. It is connected to the rest of the theater only by a single staircase from the first floor. The second story has offices for the hotel, which are furnished with gypsum board walls, dropped ceilings, and carpeted floors. The east wall has a stair to the hotel.[55] When the Hudson Theatre reopened in 2017, a VIP lounge was installed on the second story, connecting to the rear of the story.[54][56] Part of the dress circle was demolished to make way for restroom stalls.[43]

The third and fourth stories on 44th Street were refitted with two residential apartments, one on each story, after the theater had closed in the late 20th century. These apartments fell into disrepair but retained many original decorative elements as of 2016[update].[55]

History

Original Broadway run

Times Square became the epicenter for large-scale theater productions between 1900 and

Development and opening

In January 1902, Harris formed the Henry B. Harris Company to lease the site from Heye.[11] That March, Heye filed plans with the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) to develop a theater and six-story office structure on the site.[9][64][65] J. B. McElfatrick was listed as the architect of record,[9][66] though the permit only concerned structural elements and fire escapes.[66] Work on the theater began on April 2, 1902,[67][26] with the Ranald H. MacDonald Construction Company as general contractor.[26][68] The Pennsylvania Electric Equipment Company was hired to construct a power plant for the theater.[69] That August, Charles Frohman was hired to select productions for the theatre during the following five years.[70][71] The original plans had called for a ten-story office building to accompany the theater, but it was never built.[26] By January 1903, Israels & Harder had submitted revised plans for the theater. Architectural and theatrical publications continued to refer to McElfatrick as the architect until early 1904.[66]

Actors Robert Edeson and Alice Fischer formally christened the theater as the Hudson Theatre[72][73] at a ceremony on March 30, 1903.[74] The Hudson opened on October 19, 1903, with Ethel Barrymore starring in Cousin Kate.[75][76][77] Generally, the theater was positively reviewed by both architectural and theatrical critics.[35] At the opening, the Times wrote: "No richer and more tasteful theater is to be found short of the splendid Hofburg Theater in Vienna".[29][75] Theatre magazine described the Hudson as being "more than modest externally, yet boasts an auditorium which for beauty of proportions chasteness of coloring, and good taste of equipment, is unsurpassed by any theatre in America".[78] Architectural Record wrote that the decorative scheme "errs on the side of understatement", given the grandeur of the interior.[79]

From its inception, the Hudson Theatre was intended as a venue for "drawing-room comedies".[80] Such comedies included The Marriage of Kitty, which in November 1903 became the second production to be hosted at the Hudson.[81] The following year, the Hudson hosted Sunday,[80][82] where Barrymore reportedly first said "That's all there is, there isn't any more", later a popular quip.[80] Man and Superman opened at the Hudson in 1905.[77][83][84] This was the first time that its playwright, George Bernard Shaw, allowed one of his plays to be shown in a different manner than what he originally intended.[85] Barrymore returned in 1908 for the production of Lady Frederick.[86][87] The same year, Henry Harris bought the Hudson Theatre from Heye for $700,000.[10][88][89]

Renee Harris operation

Henry Harris died on the RMS Titanic when it sank in 1912.[90][91][92] All of his theaters were closed for one night in his memory,[93] and his memorial service was hosted at the Hudson.[94] Harris's wife Renee survived the Titanic with minor injuries[93][95] and took over the Hudson's operation, in doing so becoming one of the first women to be a Broadway producer.[32] Early on, Renee Harris was named as the "estate of Henry B. Harris" in production credits, as with Lady Windermere's Fan,[88] which premiered in 1914.[96][97]

Some of Renee Harris's productions had at least 300 performances, including Friendly Enemies (1918),[88][98] Clarence (1919),[99][100] and So This Is London (1922).[88][101][a] George M. Cohan presented several productions at the Hudson,[103] including Song and Dance Man (1924),[104][105] American Born (1925),[106][107] and Whispering Friends (1928).[108][109] Howard Schnebbe leased the Hudson Theatre in May 1928 after Renee Harris announced her intention to take a break from theatrical management.[110][111] Later that year, a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article said eight of the theater's original employees were still on the payroll, including Schnebbe and his brother Alan.[88][112] The Hudson's performances during the late 1920s also included Black musicals such as Hot Chocolates (1929)[113][114] and Messin' Around (1929).[103][115]

During the late 1920s (possibly in 1929

Post-Harris era

1930s and 1940s

CBS announced in January 1934 that it had leased the Hudson Theatre and would use the stage as a studio for radio broadcasts.[129][130][131] The move followed an unsuccessful attempt to take over the unused rooftop theater at the New Amsterdam Theatre.[131] The studio was dedicated on February 3, 1934, with free admission to the broadcasts.[132][133] As part of the renovation, a commercial booth and an announcer's booth replaced the box seating on the first floor.[99] The Hudson was known as CBS Radio Playhouse Number 1 during this time.[134] The CBS studio was relatively short-lived, only operating until 1937.[118][135]

In January 1937,

1950s and 1960s

NBC purchased the Hudson Theatre in June 1950[154][155] for $595,000,[156] and the theater became a television studio for NBC.[135][157][158] Detective Story, which then was being produced at the Hudson, had to be moved to the Broadhurst because NBC wanted to move into the Hudson immediately.[155] At that time, several Broadway theaters had been converted to TV studios due to a lack of studio space in New York City.[159] The shows at the studio included Broadway Open House and The Tonight Show.[134] Steve Allen and Jack Paar, the first and second hosts of The Tonight Show, both hosted at the Hudson.[158][160] Allen conducted his "Man on the Street" interviews outside the theater's stage entrances on 45th Street.[160] In November 1958, NBC offered the Hudson for sale at $855,000,[156] in part because many of the network's productions had since moved to Hollywood.[161] After unsuccessfully trying to find a buyer for several months,[161] NBC decided to renovate the theater back into a Broadway venue on its own.[161][162]

The production Toys in the Attic was announced for the Hudson Theatre in late 1959.[163][164] Toys in the Attic opened the following year,[157][165] becoming one of the few successful Broadway productions during the theater's third run.[134] NBC agreed in September 1961 to sell the theater for $1.1 million to Samuel Lehrer,[166] who wished to replace it with a parking garage.[167] NBC said it could not find any theatrical company interested in the site.[166][168] Theatrical groups heavily opposed the plans,[169] and Robert Breen, a producer who had lived in the 44th Street wing since 1942, refused to move out.[170] The theater's uncertain status meant that productions could run only a few weeks at a time, so the theater stood empty for long periods.[171] In May 1962, NBC agreed to sell the theater for $1.25 million to Sommer Brothers Construction, which planned an office and garage building on the site.[172][173] After Strange Interlude played the theater in 1963,[174][175] the theater was vacant for two years.[160]

The Sommer Brothers never redeveloped the Hudson Theatre's site because they could not acquire enough land on 45th Street for their office development. As a result, in 1965, they placed the theater for sale.

Post-Broadway

Adult films and cinema

The United States Steel Corporation and Carnegie Pension Fund had acquired the site in 1968 and leased it to Durst.[186] The theater was renamed the Avon-Hudson in 1968, becoming a pornographic theater.[134] It was the flagship venue of the Avon porn-theater chain.[187] In December 1972, the theater's license was temporarily suspended due to "disorderly conduct" and "conspiracy to show obscene films",[188] but the theater continued to operate anyway.[187] By 1975, U.S. Steel was attempting to remove pornographic shows from the theater.[158][186] Avon was forced to shut down its pornographic productions at the Hudson that April, relocating them to the nearby Henry Miller Theatre.[189] Avon unsuccessfully sued U.S. Steel over the eviction and then allegedly ripped out seats before leaving.[190] The theater was part of the "Bond site", owned by William J. Dwyer & Company,[191] which itself represented U.S. Steel.[190]

In late 1975, Dwyer reopened the Hudson Theatre as a cinema following a renovation.[190][192] The theater screened The Hiding Place for several weeks and was then empty again, but Dwyer wished specifically to avoid showing porn features, choosing instead to air budget productions.[193] After failing to attract enough visitors with a $1 ticket price, the Hudson shifted to airing Spanish-language films,[194] then to running features such as Jaws.[195] Irwin Meyer and Stephen R. Friedman then considered converting the Hudson back into a Broadway venue.[196] In April 1981, following a $1.5 million renovation by Ron Delsener,[197][198] the Hudson Theatre reopened as the Savoy dinner club.[199][200] The club hosted performances by such personalities as Peter Allen, Miles Davis, and James Taylor.[201][18] After hosting rock and similar genres, the Savoy closed for several months, reopening in July 1982.[200]

Conversion to hotel conference center

The theater was closed by 1983, and Harry Macklowe acquired the Hudson Theatre the next May.[202] He acquired several other properties on the block in the mid-1980s.[203] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated both the facade and the interior as landmarks on November 17, 1987.[204] This was part of the LPC's wide-ranging effort in 1987 to grant landmark status to Broadway theaters.[205] The New York City Board of Estimate ratified the designations in March 1988.[206]

Macklowe developed the surrounding lots into the Hotel Macklowe (later the Millennium Times Square New York) in 1988.[207] The Hudson was incorporated into the hotel as a conference center and auditorium space.[208] The modifications included preserving the landmarked decorations, including the Tiffany glass, marble stairs, and woodwork, as well as refurbishing the seating. A new deck, dressing rooms, and stage rigging were added, and a projectionists' booth and a Dolby sound system were installed.[201] During the hotel's construction, models of guestrooms and conference rooms were built on the Hudson's stage.[209]

The Hudson underwent a $7 million renovation to convert it into a conference center for corporate meetings, fashion shows, and product launches.[201] Among the events in the conference center was the World Chess Championship 1990, when Soviet grandmasters Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov competed in New York City's first World Chess Championship since 1907.[210] The championship took place while the renovation was still ongoing. The Hotel Macklowe's general manager said he was planning to show six to twelve theatrical productions each year in the theater.[201] The hotel's management wished to attract fashion shows to the conference center as well, despite the relatively small size of the Hudson's stage.[211] In addition to independent corporate events,[212] weddings could be hosted in the theater.[213] Starting in November 2004, Jablonski Berkowitz Conservation restored the theater;[214] the $1.2 million project lasted a year, with work occurring between events and seminars.[215] The project included restoring the theater's Tiffany glass decorations.[214][216]

Broadway revival

During March 2015, the media reported that Howard Panter of the British company Ambassador Theatre Group (ATG) might convert the Hudson back into a Broadway theater.[217] That December, an ATG subsidiary signed a lease with M&C Hotels with the intention of converting the Hudson back to a Broadway venue.[218][217][219] The renovation included technical upgrades as well as expansions to the backstage and front of house areas.[218] The Tony Awards Administration Committee ruled in October 2016 that the Hudson Theatre was a Tony-eligible theater, with "970 seats without the use of the orchestra pit and 948 seats when the orchestra pit is utilized by a production".[220] The New York state government also nominated the Hudson Theatre for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[221][222] The theater was added to the NRHP on November 15, 2016.[1]

The Hudson reopened with a revival of the Stephen Sondheim musical Sunday in the Park with George.[223] Stars Jake Gyllenhaal and Annaleigh Ashford participated in a ribbon-cutting ceremony on February 8, 2017.[224][225] The Hudson became the 41st Broadway theater and was both the newest and oldest Broadway theater in operation.[32][217] The reopened Hudson hosted productions such as 1984 (2017),[226] The Parisian Woman (2017),[227] Head over Heels (2018),[228] Burn This (2019),[229] and American Utopia (2019).[230]

The theater closed on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[231] Another engagement of American Utopia, planned for the Hudson before the pandemic,[232][233] moved to the St. James Theatre.[234] The Hudson reopened on February 22, 2022, with previews of Plaza Suite,[235] which officially ran from March to July 2022.[236][237] This was followed in October 2022 by a limited revival of Death of a Salesman,[238][239] which ran for three months.[240] A revival of A Doll's House opened at the Hudson in March 2023, running for three months.[241][242] ATG and Jujamcyn Theaters also agreed to merge in early 2023; the combined company operated seven Broadway theaters, including the Hudson.[243][244] Comedian Alex Edelman's one-man show Just for Us opened at the Hudson in June 2023 and ran for eight weeks,[245][246] and a revival of Merrily We Roll Along opened in October 2023 and is scheduled to run at the theater until July 2024.[247]

Notable productions

Hudson Theatre

Productions are listed by the year of their first performance. This list only includes Broadway shows; it does not include other live shows or films presented at the theater. Live shows that were presented when the theater operated as the Savoy nightclub are listed under § The Savoy.[248][249]

- 1903: The Marriage of Kitty[82][84]

- 1905: Man and Superman[77][84]

- 1907: Brewster's Millions[250][251]

- 1908: Lady Frederick[86][87]

- 1909: Arsène Lupin[252][253]

- 1912: Frou-Frou[252][254]

- 1913: General John Regan[96][255]

- 1914: Lady Windermere's Fan[96][97]

- 1915: Alice in Wonderland[96][256]

- 1917: Our Betters[257][258]

- 1918: Friendly Enemies[257][98]

- 1922: The Voice From the Minaret[259][260]

- 1922:

- 1922: So This Is London[101][259]

- 1924: The Fake[262][263]

- 1926: The Noose[262][264]

- 1927: The Plough and the Stars[265][266]

- 1929: Hot Chocolates[114][265]

- 1930: The Inspector General[125][267]

- 1932: The Show-off[125][126]

- 1937: An Enemy of the People[139][140]

- 1937: The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse[141][144]

- 1938: Good Hunting[144][268]

- 1939:

- 1940: Love for Love[269][270]

- 1941: All Men Are Alike[269][271]

- 1943: Run, Little Chillun[269][272]

- 1943: Arsenic and Old Lace[147][269]

- 1945: State of the Union[151][152]

- 1949: Detective Story[151][153]

- 1960: Toys in the Attic[273][165]

- 1962: Ross[184][274]

- 1963: Strange Interlude[184][174]

- 1967: How to Be a Jewish Mother[184][185]

- 2017: Sunday in the Park with George[275]

- 2017: 1984[226]

- 2017: The Parisian Woman[227]

- 2018: Head over Heels[228]

- 2019: Burn This[229]

- 2019: American Utopia[230]

- 2022: Plaza Suite[236][237]

- 2022: Death of a Salesman[238][239]

- 2023: A Doll's House[241][242]

- 2023: Just for Us[245][246]

- 2023: Merrily We Roll Along[247]

The Savoy

- 1981: Genesis[276]

- 1983: King Sunny Adé and his African Beats[277]

Box office record

Plaza Suite previously set the Hudson Theatre's box-office record with a gross of US$1,708,387 over one week in June 2022.[278] The record as of 2023[update] is held by Merrily We Roll Along, which grossed US$1,471,644 over one week in November 2023.[279]

See also

- List of Broadway theaters

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places 2016 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2016. p. 187. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 1.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 1; National Park Service 2016, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d "153 West 44 Street, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2016, p. 4.

- ^ "The New Lyceum Theatre". New-York Tribune. February 6, 1902. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Projected Buildings". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 69, no. 1776. March 29, 1902. p. 577. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Hudson Theatre Sold". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 81, no. 2089. March 28, 1908. p. 560. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 6; National Park Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 10; National Park Service 2016, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 10; National Park Service 2016, p. 24.

- ^ ProQuest 2544916916.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15; National Park Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16; National Park Service 2016, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 15–16; National Park Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16; National Park Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16; National Park Service 2016, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Park Service 2016, p. 6.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2016, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2016, p. 26.

- ^ ProQuest 571479599.

- ^ from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2016, p. 27.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2016, p. 8.

- ^ from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 17; National Park Service 2016, p. 8.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, pp. 17–18; National Park Service 2016, p. 8.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 14.

- ^ a b c "The Hudson Theatre". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 36, no. 5. February 1904. p. 200. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 18; National Park Service 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 18.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2016, p. 9.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 18; National Park Service 2016, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Park Service 2016, p. 10.

- ^ from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 123.

- ^ "Hudson Theatre Seating Chart & Map". SeatGeek. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "New York's abandoned Hudson Theatre revived by ATG". The Stage. February 13, 2017. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 19; National Park Service 2016, p. 9.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 20; National Park Service 2016, p. 10.

- ^ "Ticket Insurance & Accessibility". The Hudson Theatre Broadway. October 30, 2021. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 19; National Park Service 2016, p. 10.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 11.

- ISBN 978-0-02-925000-6. Archivedfrom the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 19.

- ^ a b "Hudson Theatre". Martinez + Johnson Architecture. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2016, p. 11.

- ^ "Hudson Theatre • OTJ Architects". OTJ Architects. July 31, 2018. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Swift, Christopher (2018). "The City Performs: An Architectural History of NYC Theater". New York City College of Technology, City University of New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Theater District". New York Preservation Archive Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 2; National Park Service 2016, p. 15.

- ISBN 978-0-393-28545-1. Archivedfrom the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 4; National Park Service 2016, p. 16.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 7; National Park Service 2016, pp. 19–20.

- ^ National Park Service 2016, p. 20.

- ProQuest 571165939.

- ^ "Plans for H. B. Harris's Hudson Theatre". The Sun. March 27, 1902. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 12; National Park Service 2016, p. 22.

- ^ "Work Begun on a New Theatre". New-York Tribune. April 3, 1902. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Estimates Receivable". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 69, no. 1777. April 5, 1902. p. 600. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Latest News in Real Estate". The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 25, 1902. p. 14. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Notes of the Stage". New-York Tribune. August 2, 1902. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The New Hudson Theater". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 12, 1903. p. 16. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gossip of the Stage". Times Union. April 11, 1903. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "New Hudson Theatre Opened". The Sun. October 20, 1903. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2013, p. 123; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "New York's Splendid New Theatres" (PDF). Theatre. Vol. 3. 1903. p. 296. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ David, A.C. (January 1901). "The New Theaters of New York" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 16. p. 54. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, p. 27.

- ProQuest 571417989.

- ^ ProQuest 571516125.

- ProQuest 571701977.

- ^ a b c "The Marriage of Kitty Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. December 18, 1914. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 30, 1903). "The Marriage of Kitty – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15; National Park Service 2016, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15; National Park Service 2016, p. 28.

- ^ a b "Lady Frederick Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 1, 1909. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 9, 1908). "Lady Frederick – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2016, p. 28.

- from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 123; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 8; National Park Service 2016, p. 21.

- ^ "Henry B. Harris". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 16, 1912. p. 5. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 8; National Park Service 2016, p. 21.

- ProQuest 574900045.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 25.

- ^ a b "Lady Windermere's Fan Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 26, 1932. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 30, 1914). "Lady Windermere's Fan – Broadway Play – 1914 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b "Friendly Enemies Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. August 1, 1919. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (July 22, 1918). "Friendly Enemies – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, p. 28.

- ^ "Clarence Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. June 1, 1920. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (September 20, 1919). "Clarence – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b "So This Is London Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. June 1, 1923. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (August 30, 1922). "So This Is London – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 26–27; National Park Service 2016, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14.

- ^ "The Song and Dance Man Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. June 16, 1930. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "American Born Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. December 1, 1925. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 31, 1923). "The Song and Dance Man – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "Whispering Friends Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. May 26, 1928. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (February 20, 1928). "Whispering Friends – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hudson Theater is Now Aged Twenty-six". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 9, 1928. p. 66. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Bloom 2013, pp. 124–125; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14.

- ^ a b "Hot Chocolates Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. June 4, 1929. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (June 20, 1929). "Hot Chocolates – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1114847605.

- ^ from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, p. 28.

- ProQuest 1114234754.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1114160021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 99691945.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 30.

- ^ a b "The Show Off Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 5, 1924. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 12, 1932). "The Show Off – Broadway Play – 1932 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "Hudson Theater is a Beehive Again". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 29, 1933. p. 30. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 150508003.

- ^ ProQuest 1505555855.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1114785013.

- ^ a b c d Bloom 2013, p. 124.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-486-40244-4.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1222211110.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 31.

- ^ a b "An Enemy of the People Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 15, 1924. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (February 15, 1937). "An Enemy of the People – Broadway Play – 1937 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b "The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. May 8, 1937. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 2, 1937). "The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Lew Leslie's Blackbirds of 1939 Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 18, 1939. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (February 11, 1939). "Lew Leslie's Blackbirds of 1939 – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 31.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1627591719.

- ^ a b c "Arsenic and Old Lace Broadway @ Fulton Theatre". Playbill. September 25, 1943. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (January 10, 1941). "Arsenic and Old Lace – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ National Park Service 2016, pp. 28–29.

- ProQuest 1325067594.

- ProQuest 1653910508.

- ^ a b c d Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 33.

- ^ a b "State of the Union Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 28, 1946. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 14, 1945). "State of the Union – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b "Detective Story Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. July 3, 1950. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 23, 1949). "Detective Story – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1285970805.

- ^ ProQuest 962768513.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, p. 29.

- ^ ProQuest 1285992414.

- ProQuest 1285972745.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14; National Park Service 2016, p. 29.

- ^ ProQuest 1017038110.

- ProQuest 1327419926.

- ProQuest 1017060881.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Toys in the Attic Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. March 1, 1960. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (February 25, 1960). "Toys in the Attic – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ ProQuest 1327032619.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1326107157.

- from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1032416883.

- ^ a b "Strange Interlude Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. May 27, 1963. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 11, 1963). "Strange Interlude – Broadway Play – 1963 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on April 25, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1017115088.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ProQuest 133058401.

- from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ProQuest 1017154398.

- ProQuest 963102912.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 34.

- ^ a b "How to Be a Jewish Mother Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 13, 1968. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 28, 1967). "How to Be a Jewish Mother – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1032458603.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1286009108.

- ^ ProQuest 1401274097.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ProQuest 1401278694.

- ProQuest 1286036213.

- ProQuest 1286050921.

- ProQuest 1401320664.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15.

- ^ from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 962916908.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 648–649.

- from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- OL 22741487M.

- from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ProQuest 1862428180.

- from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Millennium Hotel Broadway". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 362308455.

- from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Viagas, Robert (December 16, 2015). "Hudson Theatre Will Be Reopened as Broadway House". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Gerard, Jeremy (December 16, 2015). "Ambassador Theatre Group Acquires New York's Hudson Theatre For Broadway Shows". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (October 14, 2016). "Tony Administration Committee Rules on Cats and Paramour". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Sugar, Rachel (September 29, 2016). "Revamped Broadway theater may gain national historic recognition". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (September 30, 2016). "Broadway's Hudson Theatre Being Considered for National Register of Historic Places". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (February 8, 2017). "Broadway's Newest—and Oldest—Theatre Relights With the Help of Two Stars". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "Jake Gyllenhaal and Annaleigh Ashford Help Open Broadway's New Hudson Theatre". TheaterMania. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "1984 Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. May 18, 2017. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League. "1984 – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ a b "The Parisian Woman Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League. "The Parisian Woman – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ a b "Head Over Heels Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 6, 2019. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League. "Head Over Heels – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ a b "Burn This Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. March 15, 2019. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League. "Burn This – Broadway Play – 2019 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ a b "David Byrne's American Utopia Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 16, 2020. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Greg (October 14, 2020). "'David Byrne's American Utopia' Announces Broadway Return, Premiere Date". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (October 14, 2020). "David Byrne's American Utopia Sets 2021 Date for Broadway Return". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Greg (June 17, 2021). "'David Byrne's American Utopia' Finds Home On Broadway For September Return". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ ""Plaza Suite," starring Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick, starts previews on Broadway". CBS News. February 26, 2022. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "Plaza Suite (Broadway, Hudson Theatre, 2022)". Playbill. September 10, 2019. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

The Broadway League. "Plaza Suite – Broadway Play – 2022 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Death of a Salesman (Broadway, Hudson Theatre, 2022)". Playbill. June 1, 2022. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

The Broadway League. "Death of a Salesman – Broadway Play – 2022 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022. - ^ from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "Catch 'Em Before They Close: Here's Everything Leaving Broadway This Month". NBC New York. January 8, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b The Broadway League. "A Doll's House – Broadway Play – 2023 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

"A Doll's House (Broadway, Hudson Theatre, 2023)". Playbill. November 29, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2023. - ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ Culwell-Block, Logan (February 14, 2023). "Broadway Theatre Owners Jujamcyn and Ambassador Theatre Group Joining Forces". Playbill. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ a b The Broadway League. "Just For Us – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

"Just For Us (Broadway, Hudson Theatre, 2023)". Playbill. April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023. - ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ a b The Broadway League. "Merrily We Roll Along – Broadway Musical – 2023 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

"Merrily We Roll Along (Broadway, 2023)". Playbill. December 16, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2023. - ^ The Broadway League (October 9, 2022). "Hudson Theatre – New York, NY". IBDB. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Hudson Theatre (1903) New York, NY". Playbill. July 22, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 23.

- ^ "Brewster's Millions Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. December 31, 1906. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 31, 1906). "Brewster's Millions – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 7, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 24.

- ^ "Arsene Lupin Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. August 26, 1909. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (August 26, 1909). "Arsene Lupin – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Frou-frou Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. June 5, 1902. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 18, 1912). "Frou-Frou – Broadway Play – 1912 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "General John Regan Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. January 29, 1930. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 23, 1915). "Alice in Wonderland – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Alice in Wonderland Broadway @ Booth Theatre". Playbill. April 1, 1915. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 10, 1913). "General John Regan – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 26.

- ^ "Our Betters Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 20, 1928. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (March 12, 1917). "Our Betters – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 27.

- ^ "The Voice from the Minaret Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 1, 1922. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (January 30, 1922). "The Voice From the Minaret – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Fedora Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. May 22, 1905. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (February 10, 1922). "Fedora – Broadway Play – 1922 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 28.

- ^ "The Fake Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. December 1, 1924. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (October 6, 1924). "The Fake – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "The Noose Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. April 1, 1927. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (October 20, 1926). "The Noose – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 123; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 29.

- ^ "The Plough and the Stars Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. November 12, 1934. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 28, 1927). "The Plough and the Stars – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "The Inspector General Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. April 30, 1923. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 23, 1930). "The Inspector General – Broadway Play – 1930 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Good Hunting Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. November 30, 1938. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (November 21, 1938). "Good Hunting – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on February 27, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 32.

- ^ "Love for Love Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. March 31, 1925. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (June 3, 1940). "Love for Love – Broadway Play – 1940 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "All Men Are Alike Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. October 13, 1941. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (October 6, 1941). "All Men Are Alike – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Run, Little Chillun Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. March 1, 1933. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (August 11, 1943). "Run, Little Chillun – Broadway Play – 1943 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ Bloom 2013, p. 124; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 34

- ^ "Ross Broadway @ Eugene O'Neill Theatre". Playbill. April 3, 1962. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League (December 26, 1961). "Ross – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022. - ^ "Sunday in the Park with George Broadway @ Hudson Theatre". Playbill. February 11, 2017. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

The Broadway League. "Sunday in the Park with George – Broadway Musical – 2017 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "Broadway's 'Plaza Suite' sets new box office record". UPI. June 15, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ Evans, Greg (October 3, 2023). "'Merrily We Roll Along' Breaks Another House Record With $1.5M Gross – Broadway Box Office". Deadline. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

Sources

- Bloom, Ken (2013). Routledge Guide to Broadway. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-87117-8.

- Hudson Theatre (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 25, 2016.

- Hudson Theater (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 17, 1987.

- Hudson Theater Interior (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 17, 1987.

External links

- Official website

- Hudson Theatre at the Internet Broadway Database

- Hudson Theatre (New York, N. Y.), Museum of the City of New York website