Walter Krupinski

Walter Krupinski | |

|---|---|

JaBoG 33 | |

| Battles / wars | See battles

|

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves |

Walter Krupinski (11 November 1920 – 7 October 2000) was a German

Born in the Weimar Republic in 1920, Krupinski joined the Luftwaffe in 1939 and completed his flight training in 1940. Flying with

After the war, Krupinski joined the German Air Force of the Bundeswehr, serving until 1976 when he was forced into early retirement. Krupinski died in Neunkirchen-Seelscheid on 7 October 2000.

Childhood, education and early career

Krupinski was born on 11 November 1920, in the town of

When the naval branch of

On 1 October, Krupinski joined the military and received his basic training with Fliegerausbildungs-Regiment 10 (10th Aviators Training Regiment) based in

Following two weeks of vacation, Krupinski completed his training at Jagdfliegerschule 5 (5th fighter pilot school) in Wien-Schwechat to which he was posted on 1 July 1940. Jagdfliegerschule 5 at the time was under the command of the World War I flying ace and recipient of the Pour le Mérite Eduard Ritter von Schleich. One of his course mates was Hans-Joachim Marseille, who had been posted to the Jagdfliegerschule 5 in late 1939 but had not yet graduated out of disciplinary reasons.[9] His three-roommates at the school were Walter Nowotny, Paul Galland, the brother of Adolf Galland, and Peter Göring, a nephew of the Reichsmarschall (Empire Marshal) Hermann Göring.[10]

World War II

After completing his flight training at Jagdfliegerschule 5, Krupinski was sent to Ergänzungsjagdgruppe Merseburg, a supplementary training unit based in Merseburg, on 1 October 1940. On 15 October, he was then posted to the Ergänzungsstaffel (training squadron) of Jagdgeschwader 52 (JG 52—52nd Fighter Wing).[11] The Ergänzungsstaffel was headed by Oberleutnant Werner Lederer and based at Krefeld Airfield where the pilots received further training flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E.[12] At Merseburg, Krupinski met and befriended Gerhard Barkhorn and Willi Nemitz.[13] On 13 May 1940, for his service he was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class (Eisernes Kreuz zweiter Klasse).[14]

On 1 February 1941, Krupinski was transferred to 6. Staffel.[Note 2] 6. Staffel at the time was under the command of Staffelkapitän (squadron leader) Rudolf Resch. Resch later gave Krupinski the nickname "Graf Punski" ("Count Punski") or sometimes just "Der Graf" ("The Count"). The nickname had its origins in a late-night conversation between Krupinski and Resch. His father was a professor of Slavic studies in Dresden. When Krupinski tried to explain his East Prussian origin, Resch informed him that the ending in "-ski" or "-zky" denoted a landowner, or that it indicated a Freiherr ("free lord"), and thus the lowest level in the medieval noble hierarchy in the East. The witty banter which then followed, led at first in his squadron, then in his group and eventually in the entire German fighter force to his nickname which stuck with for the rest of his life.[15] His Staffel was subordinated to II. Gruppe of JG 52 which was headed by Hauptmann Erich Woitke.[16]

Operation Barbarossa

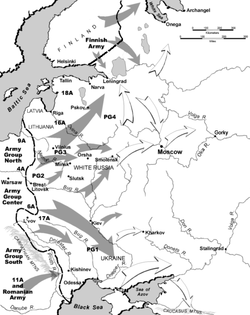

In preparation of

II. Gruppe was ordered to relocate to

On 2 October, German forces launched

Eastern Front

In late January 1942, II. Gruppe was withdrawn from the Eastern Front and sent to Jesau near Königsberg for a period of recuperation and replenishment, arriving on 24 January 1942.[30] In Jesau, the Gruppe received many factory new Bf 109 F-4 aircraft. On 14 April, II. Gruppe received orders to move to Pilsen, present-day Plzeň in the Czech Republic, for relocation to the Eastern Front.[31] The Gruppe had also received a new commander, Woitke had been transferred and was replaced by Hauptmann Johannes Steinhoff.[32] Following his home leave, Krupinski had rejoined his unit at Jesau.[33] The Gruppe then moved to Wien-Schwechat on 24 April before flying to Zürichtal, present-day Solote Pole, a village near the urban settlement Kirovske in the Crimea. There, II. Gruppe participated in Operation Trappenjagd, a German counterattack during the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, launched on 8 May.[31]

Following a series of relocations, including a short deployment on the Crimea, the Gruppe was then ordered to the airfield named Kharkov-Waitschenko on 14 May and participated in the

On 28 June, the

In September 1942, II. Gruppe was ordered into the

Following his 50th aerial victory, Krupinski was awarded the

While Soviet forces launched

Squadron leader

On 15 March, Krupinski was transferred back to JG 52 where was made Staffelkapitän of 7. Staffel. The Staffel was subordinated to III. Gruppe under the command of Major Hubertus von Bonin.[54] At the time, III. Gruppe was based at an airfield near Kerch and was fighting over the Kuban bridgehead.[55] On 1 April, III. Gruppe moved to Taman where it was headquartered until 2 July.[56] Krupinski claimed his first aerial victory of the year and 67th in total on 2 May when he shot down a Yakovlev Yak-1 fighter southwest of Abinsk[57] Fighting over the Kuban bridgehead, Krupinski's aerial victories increased to 88 claims by the end of June.[58]

JG 52 moved north in preparation for Operation Citadel and the Battle of Kursk. III. Gruppe arrived in Ugrim, located south of Kursk, on 3 July.[59] Hauptmann Günther Rall, who had already served as acting Gruppenkommandeur (group commander) of III. Gruppe in February and March 1943, officially replaced Bonin in this position on 5 July 1943.[54] That day, Krupinski claimed two LaGG-3 fighters shot down but was also severely injured in a landing accident at Ugrim. Krupinski collided with a Bf 109 taking off, causing his Bf 109 G-6 (Werknummer 20062) to flip over, severely injuring him.[60] He had sustained injuries to the head, including lacerations, a fracture of the parietal bone and a rib. After immediate treatment, Krupinski was flown to Heiligenbein, present-day Mamonovo. He was then taken to a hospital at Braunsberg for further convalescence.[61] He returned to his unit on 6 August.[62] During his absence, Leutnant Erich Hartmann, who went on to become the highest scoring fighter pilot of the war, temporarily commanded 7.Staffel.[54]

On 18 August 1943, Krupinski was credited with his 100th aerial victory. He was the 51st Luftwaffe pilot to achieve the century mark.

Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross

Following his 174th aerial victory, Krupinski was awarded the

Both Krupinski and Hartmann were ordered to the

Defense of the Reich

On 11 April 1944, the Staffelkapitän of 2. Staffel of

After the Allied

Following his convalescence, he was appointed Gruppenkommandeur of III. Gruppe of

On 25 March 1945, III. Gruppe of JG 26 was disbanded.

Jagdverband 44

Following the dismissal of Generalleutnant Adolf Galland as General der Jagdflieger, Galland was given the opportunity by Hitler to prove his ideas about the Me 262 jet fighter. He had hoped that the Me 262 would compensate for the numerical superiority of the Allies. In consequence, Galland formed

At 3:00 pm on 24 April 1945, Krupinski was one of four pilots to take off from Munich-Riem to intercept a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) Martin B-26 Marauder aircraft formation. Günther Lützow, who failed to return from this mission, led the flight of four. Lützow's fate remains unknown to this date.[85] Later that day, Krupinski led a flight of Me 262 fighters against Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. Damaged by the defensive fire of a bomber he believed to have damaged, he then fired at an escorting Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter. The two fighters collided and the P-47 fell away. Krupinski did not claim an aerial victory.[86]

Prisoner of war

On 4 May, JV 44 surrendered to U.S. forces at

In June, Krupinski was taken to Southampton and then with a ship to Cherbourg where he arrived on 6 June. Upon arrival, he was beaten by a French soldier and butted over the head resulting in a fractured skull. The injury was so severe that he was taken to the Luftwaffe hospital at München-Oberföhring and to the US Army Hospital 1022 B at Wasserburg am Inn on 24 July. He was discharged as a prisoner of war on 28 September.[89]

Later life and service

Krupinski was picked up at Wasserburg by his friend Barkhorn who took him home to his family at Tegernsee. There, Krupinski learned that his wife and daughter had found refuge with her oldest sister in Bad Salzschlirf. Since Krupinski was still suffering from his head injury, the family lived off his wife’s income who was working as a waitress for the US garrison at Bad Salzschlirf.[90]

Gehlen Organization

The former General

With the German Air Force

Krupinski entered the Amt Blank (Blank Agency), named after

Given the rank of major in 1957, Krupinski went to lead

Summary of career

Aerial victory claims

According to US historian David T. Zabecki, Krupinski was credited with 197 aerial victories.[101] Spick also list Krupinski with 197 aerial victories, claimed in approximately 1,100 combat missions. This figure includes 177 aerial victories claimed over the Eastern Front and 20 in the western theatre of operations and includes one heavy bomber.[102] Mathews and Foreman, authors of Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims, researched the German Federal Archives and found records for 197 aerial victory claims, plus five further unconfirmed claims. This figure of confirmed claims includes 178 aerial victories on the Eastern Front and 19 on the Western Front, including one four-engined bomber and two victories with the Me 262 jet fighter.[103]

Awards

- Wound Badge in Gold (January 1945)[68]

- German Cross in Gold on 27 August 1942 as Leutnant in the 6./Jagdgeschwader 52[106]

- Iron Cross (1939)

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

- Knight's Cross on 29 October 1942 as Leutnant and pilot in the 6./Jagdgeschwader 52[108][109]

- 415th Oak Leaves on 2 March 1944 as Oberleutnant and Staffelkapitän of the 7./Jagdgeschwader 52[108][110]

Notes

- ^ Flight training in the Luftwaffe progressed through the levels A1, A2 and B1, B2, referred to as A/B flight training. A training included theoretical and practical training in aerobatics, navigation, long-distance flights and dead-stick landings. The B courses included high-altitude flights, instrument flights, night landings and training to handle the aircraft in difficult situations.[7]

- ^ For an explanation of Luftwaffe unit designations see Organization of the Luftwaffe during World War II.

- ^ According to Obermaier in May 1942.[105]

References

Citations

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 152.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 22, 314.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Bergström, Antipov & Sundin 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 30, 314.

- ^ Prien et al. 2002, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Dixon 2023, p. 279.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Prien et al. 2002, p. 151.

- ^ Prien et al. 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Prien et al. 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b Barbas 2005, p. 329.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Prien et al. 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Prien et al. 2003, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Barbas 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Prien et al. 2003, p. 33.

- ^ a b Prien et al. 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 330.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 59.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, p. 446.

- ^ a b Prien et al. 2006, p. 447.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Barbas 2005, pp. 101–103.

- ^ a b Barbas 2005, p. 103.

- ^ a b Barbas 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 331.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, pp. 482–483.

- ^ Weal 2004, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Bergström & Pegg 2003, p. 364.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, p. 503.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, p. 475.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, p. 504.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Stockert 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 309.

- ^ Barbas 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Weal 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b c Prien et al. 2012, p. 474.

- ^ Barbas 2010, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Barbas 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Prien et al. 2012, p. 480.

- ^ Barbas 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Barbas 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Prien et al. 2012, pp. 482, 497.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 97.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Obermaier 1989, p. 243.

- ^ Barbas 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 100.

- ^ Prien et al. 2006, p. 474.

- ^ Prien et al. 2012, p. 491.

- ^ a b c d Stockert 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Mombeek 2010, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Prien & Rodeike 1996b, p. 1616.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 17, 143, 149.

- ^ Prien & Rodeike 1996a, pp. 1121, 1196.

- ^ Prien et al. 2019, p. 86.

- ^ Caldwell 1998, p. 358.

- ^ Caldwell 1998, p. 485.

- ^ Caldwell 1998, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Caldwell 1998, p. 389.

- ^ Caldwell 1998, p. 449.

- ^ Forsyth 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Braatz 2005, p. 365.

- ^ Heaton & Lewis 2012, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Forsyth 2008, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 170, 175.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 177–181.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 193.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 189.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 194.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 195.

- ^ Barbas 2014, p. 196.

- ^ Barbas 2014, p. 197.

- ^ Braatz 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Braatz 2010, pp. 304–305, 315.

- ^ Zabecki 2019, p. 329.

- ^ Spick 1996, p. 228.

- ^ Mathews & Foreman 2015, pp. 696–700.

- ^ Patzwall 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Obermaier 1989, p. 61.

- ^ Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 258.

- ^ a b Thomas 1997, p. 418.

- ^ a b Scherzer 2007, p. 479.

- ^ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 276.

- ^ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 79.

Bibliography

- Barbas, Bernd (2005). Die Geschichte der II. Gruppe des Jagdgeschwaders 52 [The History of 2nd Group of Fighter Wing 52] (in German). Selbstverl. ISBN 978-3-923457-71-7.

- Barbas, Bernd (2010). Die Geschichte der III. Gruppe des Jagdgeschwaders 52 [The History of 3rd Group of Fighter Wing 52] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-94-6.

- Barbas, Bernd (2014). Das vergessene As — Der Jagdflieger Gerhard Barkhorn [The Forgotten Ace — The Fighter Pilot Gerhard Barkhorn] (in German and English). Bad Zwischenahn, Germany: Luftfahrtverlag-Start. ISBN 978-3-941437-22-7.

- ISBN 978-3-9807935-6-8.

- ISBN 978-3-9811615-5-7.

- ISBN 978-0-9721060-4-7.

- ISBN 978-1-903223-23-9.

- Caldwell, Donald L. (1998). The JG 26 War Diary Volume Two 1943–1945. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-898697-86-2.

- Dixon, Jeremy (2023). Day Fighter Aces of the Luftwaffe: Knight's Cross Holders 1939–1942. ISBN 978-1-52677-864-2.

- ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Forsyth, Robert (2008). Jagdverband 44 Squadron of Experten. Aviation Elite Units. Vol. 27. Oxford, UK: ISBN 978-1-84603-294-3.

- Heaton, Colin; Lewis, Anne-Marie (2012). The Me 262 Stormbird: From the Pilots Who Flew, Fought, and Survived It. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-0-76034-263-3.

- Mathews, Andrew Johannes; Foreman, John (2015). Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims — Volume 2 G–L. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-1-906592-19-6.

- Mombeek, Eric (2010). Eismeerjäger—Zur Geschichte des Jagdgeschwaders 5—Band 3 [Fighters in the Arctic Sea—The History of the 5th Fighter Wing—Volume 3]. Linkebeek, Belgium: ASBL, La Porte d'Hoves. ISBN 978-2-930546-02-5.

- Obermaier, Ernst (1989). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Luftwaffe Jagdflieger 1939 – 1945 [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Luftwaffe Fighter Force 1939 – 1945] (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 978-3-87341-065-7.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Patzwall, Klaus D. (2008). Der Ehrenpokal für besondere Leistung im Luftkrieg [The Honor Goblet for Outstanding Achievement in the Air War] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-08-3.

- Prien, Jochen; Rodeike, Peter (1996a). Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11—Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945: Teil 2—1944 [Jagdgeschwader 1 and 11—Operations in the Defense of the Reich from 1939 to 1945: Volume 2—1944] (in German). Vol. II 1944. Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-24-3.

- Prien, Jochen; Rodeike, Peter (1996b). Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11—Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945: Teil 3, 1944–1945 [Jagdgeschwader 1 and 11—Operations in the Defense of the Reich from 1939 to 1945: Volume 3—1944–1945] (in German). Vol. III 1944–1945. Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-25-0.

- Prien, Jochen; Stemmer, Gerhard; Rodeike, Peter; Bock, Winfried (2002). Die Jagdfliegerverbände der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945—Teil 4/II—Einsatz am Kanal und über England—26.6.1940 bis 21.6.1941 [The Fighter Units of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945—Part 4/II—Action at the Channel and over England—26 June 1940 to 21 June 1941] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-64-9.

- Prien, Jochen; Stemmer, Gerhard; Rodeike, Peter; Bock, Winfried (2003). Die Jagdfliegerverbände der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945—Teil 6/II—Unternehmen "BARBAROSSA"—Einsatz im Osten—22.6. bis 5.12.1941 [The Fighter Units of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945—Part 6/II—Operation "BARBAROSSA"—Action in the East—22 June to 5 December 1941] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-70-0.

- Prien, Jochen; Stemmer, Gerhard; Rodeike, Peter; Bock, Winfried (2006). Die Jagdfliegerverbände der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945—Teil 9/II—Vom Sommerfeldzug 1942 bis zur Niederlage von Stalingrad—1.5.1942 bis 3.2.1943 [The Fighter Units of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945—Part 9/II—From the 1942 Summer Campaign to the Defeat at Stalingrad—1 May 1942 to 3 February 1943] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-923457-77-9.

- Prien, Jochen; Stemmer, Gerhard; Rodeike, Peter; Bock, Winfried (2012). Die Jagdfliegerverbände der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945—Teil 12/II—Einsatz im Osten—4.2. bis 31.12.1943 [The Fighter Units of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945—Part 12/II—Action in the East—4 February to 31 December 1943] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Buchverlag Rogge. ISBN 978-3-942943-05-5.

- Prien, Jochen; Balke, Ulf; Stemmer, Gerhard; Bock, Winfried (2019). Die Jagdfliegerverbände der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945—Teil 13/V—Einsatz im Reichsverteidigung und im Westen—1.1. bis 31.12.1944 [The Fighter Units of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945—Part 13/V—Action in the Defense of the Reich and in the West—1 January to 31 December 1944] (in German). Eutin, Germany: Struve-Druck. ISBN 978-3-942943-21-5.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Spick, Mike (1996). Luftwaffe Fighter Aces. New York: ISBN 978-0-8041-1696-1.

- Stockert, Peter (2007). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 5 [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 5] (in German). Bad Friedrichshall, Germany: Friedrichshaller Rundblick. OCLC 76072662.

- Thomas, Franz (1997). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 1: A–K [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 1: A–K] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2299-6.

- Weal, John (2001). Bf 109 Aces of the Russian Front. Aircraft of the Aces. Vol. 37. Oxford, UK: ISBN 978-1-84176-084-1.

- Weal, John (2004). Jagdgeschwader 52: The Experten. Aviation Elite Units. Vol. 15. Oxford, UK: ISBN 978-1-84176-786-4.

- ISBN 978-1-44-086918-1.

External links

- Walter Krupinski in the German National Library catalogue

- Colin D. Heaton. "World War II: Interview with Luftwaffe Ace Walter Krupinski". Historynet.com. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Walter Krupinski". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 29. 1962. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Datum: 29. August 1966 Betr: Einwände". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 36. 1966. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Walter Krupinski". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 37. 1966. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Bei uns ist alles in die Brüche gegangen Spiegel-Gespräch mit Brigadegeneral Walter Krupinski". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 37. 1966. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Datum: 15. November 1976 Betr.: Krupinski". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 47. 1976. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Liv Ullmann, Walter Krupinski, Walter F. Mondale, Eleanor Jane, William Hall, Günter Guillaume, Charles M. Schulz". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 52. 1976. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Me 262 Ace Walter "Graf" Krupinski Interview on YouTube

- Germans Train With R.A.F. Aka German Pilots Train With The R.A.F. (1956) on YouTube

- RAF Wings For Germany (1956) on YouTube

- Imperial War Museum Interview