Bison hunting

Bison hunting (

Prehistoric and native hunting

Long before the arrival of humans in the Americas, bison hunting had been practiced by

Native American plains bison hunting

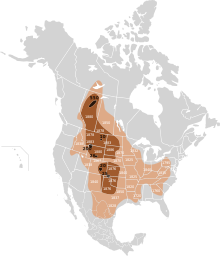

Ecology, spread, interaction with humans

The modern American bison is split into two subspecies, the

Religious rituals

Religion plays a big role in Native American bison hunting. Plains tribes generally believe that successful hunts require certain rituals. The Omaha tribe had to approach a herd in four legs. At each stop, the chiefs and the leader of the hunt would sit down and smoke and offer prayers for success.[7] The Pawnee performed the purifying Big Washing Ceremony before each tribal summer hunt to avoid scaring the bison.[8]

To Plains tribes, the buffalo is one of the most sacred animals, and they feel obligated to treat them with respect. When they are about to kill a buffalo, they will offer it a prayer. Failures in the hunt could have been attributed to poorly performed rituals.[9]

Trapping

Before the introduction of horses, bison were herded into large chutes made of rocks and willow branches (drive lines) and trapped in a corral called a buffalo pound, and then slaughtered or stampeded over cliffs, called buffalo jumps. Both pound and jump archaeological sites are found in several places in the U.S. and Canada.[citation needed]

- Buffalo jumps

In the case of a jump, large groups of people would herd the bison for several miles, forcing them into a stampede that drove the herd over a cliff.[citation needed]

The earliest evidence for buffalo jumps dates to around 1400.[citation needed]

Working on foot, a few groups of Native Americans at times used fires to channel an entire herd of buffalo over a cliff, sometimes killing far more than they could use.[citation needed]

A

- Driving herds into enclosures

In the dog days, the women of a Blackfoot camp made a curved fence of

- People surrounding herds

Henry Kelsey described a hunt on the northern plains in 1691. First, the tribe surrounded a herd. Then they would "gather themselves into a smaller Compass Keeping ye Beast still in ye middle".[14] The hunters killed as many as they could before the animals broke through the human ring.[citation needed]

- Exhausting single bison

Russel Means states that bison were killed by using a method that coyotes implemented. Coyotes will sometimes cut one bison off from the herd and chase it in a circle until the animal collapses or gives up due to exhaustion.[15]

- Driving bison on ice

During winter, Chief One Heart's camp would maneuver the game out on slick ice, where it was easier to kill with hunting weapons.[citation needed]

- Driving bison under ice

The Hidatsa near the Missouri River confined the buffalo on the weakest ice at the end of winter. When it cracked, the current swept the animals down under thicker ice. The people hauled the drowned animals ashore when they emerged downstream.[16] Although not hunted in a strict sense, the nearby Mandan secured bison, and drowned by chance, when the ice broke. A trader observed the young men "in the drift ice leap from piece to piece, often falling between, plunging under, darting up elsewhere and securing themselves upon very slippery flakes" before they brought the carcasses to land.[17]

Butchering methods and yield

The Olsen–Chubbuck archaeological site in Colorado, where buffalo herds were driven over a cliff, reveals some techniques, which may or may not have been widely used. The method involves skinning down the back to get at the tender meat just beneath the surface, the area known as the "hatched area". After the removal of the hatched area, the front legs are cut off as well as the shoulder blades. Doing so exposes the hump meat (in the Wood Bison), as well as the meat of the ribs and the Bison's inner organs. After everything was exposed, the spine was then severed and the pelvis and hind legs were removed. Finally, the neck and head were removed as one. This allowed for the tough meat to be dried and made into pemmican.[citation needed]

Castaneda saw Indigenous women butchering bison with a flint fixed on a short stick. He admired how quickly they completed the task. Blood to drink was filled in emptied guts, which were carried around the neck.[18]

Each animal produces from 200 to 400 lb (91 to 181 kg) of meat.[9]

Horse introduction and changing hunting dynamic

Horses taken from the Spanish were well-established in the nomadic hunting cultures by the early 1700s, and Indigenous groups once living east of the Great Plains moved west to hunt the larger bison population. Intertribal warfare forced the Cheyenne to give up their cornfields at Biesterfeldt village and eventually cross west of the Missouri and become the well-known horseback buffalo hunters.[19] In addition to using bison for themselves, these Indigenous groups also traded meat and robes to village-based tribes.[20]

A good horseman could easily lance or shoot enough bison to keep his tribe and family fed, as long as a herd was nearby. The bison provided meat, leather, and sinew for bows.[citation needed]

A fast-hunting horse would usually be spared and first mounted near the bison. The hunter rode on a pack horse until then.[22] Hunters with few horses ran beside the mount to the hunting grounds.[23] Accidents, sometimes fatal, happened from time to time to both rider and horse.[24][7][25]

To avoid disputes, each hunter used arrows marked in a personal way.[26][27][28] Lakota hunter Bear Face recognized his arrows by one of three "arrow wings" made of a pelican feather.[29] Castaneda wrote how it was possible to shoot an arrow right through a buffalo.[30] The Pawnees had contests as to how many bison it was possible to kill with just one bowshot. The best result was three.[31] An arrow stuck in the animal was preferred as the most lethal. It would inflict more damage with each jump and move.[32] A non-indigenous traveler credited the hunters with cutting up a bison and packing the meat on a horse in less than 15 minutes.[33]

When the bison stayed away and made hunting impossible, famine became a reality. The hard experience of starvation found its way into stories and myths. A folk tale of the Kiowa begins "Famine once struck the Kiowa People ..."[34] "The people were without food and no game could be found ..." makes an Omaha myth certain.[35] A fur trader noted how some Sioux were in want of meat at one time in 1804.[36] Starving Yanktonais passed by Fort Clark in 1836.[37]

Diminishing herds and the effects on tribes

Already Castaneda noted the typical relations of two different plains people relying heavily on the same food source: "They ... are enemies of each other."[38] The bison hunting resulted in the loss of land for many tribal nations. Indirectly, it often disturbed the rhythm of tribal life, caused economic losses and hardship, and damaged tribal autonomy. As long as bison hunting went on, intertribal warfare was omnipresent.[39][40]

Loss of land and disputes over the hunting grounds

Tribes forced away from the game-rich areas had to try their luck on the edges of the best buffalo habitats. Small tribes found it hard to do even that. Due to attacks in the 1850s and 1860s, the villages of Upper Missouri "hardly dared go into the plains to hunt buffalo".[41] The Sioux would stay near Arikara villages "and keep the bison away, so they could sell meat and hides to the Arikaras".[42]

The Kiowas have an early history in parts of present-day Montana and South Dakota. Here they fought the Cheyenne, "who challenged their right to hunt buffalo".

In 1866, the Pend d'Oreilles crossed the Rocky Mountains from the west, just to be attacked by tribes as they entered the plains. They lost 21 people. The beaten hunting party returned in a "horrible condition" and "all nearly famished".[48] Often, the attackers tried to capture dried meat, equipment, and horses during a fight.[49][50] The lack of horses owing to raids reduced the chances of securing an ample amount of meat on the hunts. In 1860, the Ponca lost 100 horses,[51] while the Mandan and Hidatsa saw the enemy disappear with 175 horses in a single raid in 1861.[52]

Conflicts between the bison-hunting tribes ranged from raids to massacres.[53][54] Camps were left without leaders. In the course of a battle, tipis and hides could be cut to pieces and tipi poles broken.[55][53] Organized bison hunts and camp moves were stopped by the enemy,[56] and villages had to flee their homes.

The Sioux burned a village of Nuptadi Mandans in the last quarter of the 18th century.[59] Other villages of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara destroyed either completely or partially in attacks are two Hidatsa villages in 1834,[60] Mitutanka on January 9, 1839[61] and Like-a-Fishhook Village in 1862.[62] The three tribes would routinely ask the U.S. army for assistance against stronger powers until the end of intertribal warfare in the area.[63]

Eighteen out of 30 prominent Poncas were killed in a surprise attack in 1824, "including the famous Smoke-maker".[64] At a stroke, the small tribe stood without any experienced leaders. In 1859, the Poncas lost two chiefs when a combined group of enemies charged a hunting camp.[65] Half a Pawnee village was set ablaze during a large-scale attack in 1843, and the Pawnee never rebuilt it. More than 60 inhabitants lost their lives, including Chief Blue Coat.[66] The otherwise numerous Small Robes band of the Piegan Blackfoot lost influence and some self-reliance after a severe River Crow attack on a moving camp at "Mountains on Both Sides" (Judith Gap, Montana) in 1845. "Their days of greatness were over."[67] In 1852, an Omaha delegation visited Washington, D.C. It would "request the federal government's protection".[68] Five different nations raided the Omaha.

19th-century bison hunts and near-extinction

In the 19th century, European settlers hunted bison almost to extinction. Fewer than 100 remained in the wild by the late 1880s.[69] Unlike Indigenous practices, where hunters took only what was needed and used the whole animal, these settlers hunted them en masse for only their skins and tongues and left the rest of the animal behind to decay on the ground.[70] After the animals rotted, their bones were collected and shipped back east in large quantities.[70]

Due to the roaming behavior of bison, their mass destruction came with relative ease to the European hunters. When one bison in a herd is killed, the other bison gather around it. Due to this pattern, the ability of a hunter to kill one bison often led to the destruction of a large herd of them.[71]

In 1889, an essay in a journal of the time observed:[72]

Thirty years ago millions of the great unwieldy animals existed on this continent. Innumerable droves roamed, comparatively undisturbed and unmolested ... Many thousands have been ruthlessly and shamefully slain every season for past twenty years or more by white hunters and tourists merely for their robes, and in sheer wanton sport, and their huge carcasses left to fester and rot, and their bleached skeletons to strew the deserts and lonely plains.

Indigenous peoples whose lives depended on the Buffalo also continued to hunt, and they were faced with having to adapt to the arrival of European settlers in the Plains. While most struggled to continue their traditional ways, other Plains cultures were forced to adapt their style of hunting. Andrew Isenberg argues that some Native people embraced the fur trade and that adapting their hunting methods to include hunting on horseback, added to the number of bison they could hunt.[73]

Commercial incentives

Commercial bison hunters also emerged at this time. Military forts often supported hunters, who would use their civilian sources near their military base. Though officers hunted bison for food and sport, professional hunters made a far larger impact on the decline of the bison population.[76] Officers stationed in Fort Hays and Wallace even had bets in their "buffalo shooting championship of the world", between "Medicine Bill" Comstock and "Buffalo Bill" Cody.[75] Some of these hunters would engage in mass bison slaughter to make a living.[citation needed]

Government involvement

The US Army sanctioned and actively endorsed the wholesale slaughter of bison herds.[77] The federal government promoted bison hunting for various reasons, primarily to pressure the native people onto the Indian reservations during times of conflict by removing their main food source.[78][79] Without the bison, native people of the plains were often forced to leave the land or starve to death. One of the biggest advocates of this strategy was General William Tecumseh Sherman. On June 26, 1869, the Army Navy Journal reported: "General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins."[80]

Similarly, Lieutenant General John M. Schofield would write in his memoirs: "With my cavalry and carbined artillery encamped in front, I wanted no other occupation in life than to ward off the savage and kill off his food until there should no longer be an Indian frontier in our beautiful country."[81] In 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant vetoed the act of Congress HR 921, which would have implemented protections against non-indigenous overhunting of buffalo.[82] Before this, Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano, had stated the following regarding complaints about non-indigenous hunting buffalo on native reservations:[83]

"While I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect on the Indians, regarding it rather as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their own labors, yet these encroachments by the non-indigenous upon the reservations set apart for the exclusive occupancy of the Indian is one prolific source of trouble in the management of the reservation Indians, and measures should be adopted to prevent such trespasses in the future, or very serious collisions may be the result."

Demonstrating clearly that he saw non-indigenous poaching of bison as a problem only because it may lead to retaliation from the Indians, and on the contrary, that he saw the extermination of the buffalo as potentially beneficial in the forced assimilation of Indians.

According to Professor David Smits: "Frustrated bluecoats, unable to deliver a punishing blow to the so-called 'Hostiles', unless they were immobilized in their winter camps, could, however, strike at a more accessible target, namely, the buffalo. That tactic also made curious sense, for in soldiers' minds the buffalo and the Plains Indian were virtually inseparable."[80]

Native American involvement

According to

Railroad involvement

After the

Hunters began arriving in masses, and trains would often slow down on their routes to allow for raised hunting. Men would either climb aboard the roofs of trains or fire shots at herds from outside their windows. As a description of this from Harper's Weekly noted: "The train is 'slowed' to a speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish."[85]

The railroad industry also wanted bison herds culled or eliminated. Herds of bison on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time. Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding through hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, bison herds could delay a train for days.[6]

Commercial hunting

Bison skins were most often used for industrial machine belts, clothing, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as Buffalo Bill Cody, killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their careers. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his count. The average prices paid the buffalo hunters from 1880 to 1884 were about as follows: For cow hides, $3; bull hides, $2.50; yearlings, $1.50; calves, $0.75; and the cost of getting the hides to market brought the cost up to about $3.50 ($89.68 accounting for inflation) per hide.[86]

The hunter would customarily locate the herd in the early morning, and station himself about 100 yd (91 m) from it, shooting the animals broadside through the lungs. Head shots were not preferred as the soft lead bullets would often flatten and fail to penetrate the skull, especially if mud was matted on the head of the animal. The bison would continue to drop until either the herd sensed danger and stampeded or perhaps a wounded animal attacked another, causing the herd to disperse. If done properly a large number of bison would be felled at one time. Following up were the skinners, who would drive a spike through the nose of each dead animal with a sledgehammer, hook up a horse team, and pull the hide from the carcass. The hides were dressed, prepared, and stacked on the wagons by other members of the organization.

For a decade after 1873, there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide-hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by Native Americans or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. It was said that the .50 caliber (12.7mm) rifles were fired so much that buffalo hunters needed at least two or three rifles to allow the barrels cool off; The Fireside Book of Guns reports that the rifles were sometimes quenched in the winter snow to expedite the process. Dodge City saw railroad cars sent East filled with stacked hides.

The building of the railroads through Colorado and Kansas split the bison herd into two parts, the southern herd and the northern herd. The last refuge of the southern herd was in the

Discussion of bison protection

As the great herds began to wane, proposals to protect the bison were discussed. In some cases, individual military officers attempted to end the mass slaughter of these buffalo.[76] William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, among others, spoke in favor of protecting the bison because he saw that the pressure on the species was too great. Yet these proposals were discouraged since it was recognized that the Plains Indians, some of the tribes often at war with the United States, depended on bison for their way of life. (Other buffalo-hunting tribes cannot tell of a single fight with the United States, namely tribes like the Assiniboine,[88] the Hidatsa,[89] the Gros Ventre,[90] the Ponca[91] and the Omaha[92]).

In 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant "pocket vetoed" a Federal bill to protect the dwindling bison herds, and in 1875 General Philip Sheridan pleaded to a joint session of Congress to slaughter the herds, to deprive the Indians of their source of food.[93] By 1884, the American Bison was close to extinction.

Subsequent settlers harvested bison bones to be sold for fertilizer. It was an important source of supplemental income for poorer farmers, which lasted from the early 1880s until the early 1890s.[94]

Early reservation era final hunts

During the 1870s and 1880s, more and more tribes went on their last great bison hunt.

Led by Chief Washakie, around 1,800 Shoshones in the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming started in October 1874. Going north, the men, women, and children crossed the border of the reservation. Scouts came back with news of buffalo near Gooseberry Creek. The hunters got around 125 bison. Fewer hunters left the reservation over the next two years and those who went focused on elk, deer, and other game.[95]

The final hunt of the Omaha in Nebraska took place in December 1876.[96]

Hidatsa rebel Crow Flies High and his group established themselves on the Fort Buford Military Reservation, North Dakota, at the start of the 1870s and hunted bison in the Yellowstone area until the game went scarce during the next decade.[97]: 14–15

Indian agents, with insufficient funds, accepted long hunting expeditions of the Flathead and Pend d'Oreille to the plains in the late 1870s.[98] In the early 1880s, the buffalo were gone.[99]

The Gros Ventre left the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana for a hunt north of Milk River in 1877.[100] Chief Jerry Running Fisher enlisted as a scout at Fort Assinniboine in 1881. "His camp stayed close to the troops when they patrolled, so they hunted undisturbed by enemy tribes."[101] Two years later, the buffalo were all but gone.

In June 1882, more than 600 Lakota and Yanktonai hunters located a big herd on the plains far west of the Standing Rock Agency. In this last hunt, they got around 5,000 animals.[102]

Bison population crash and its effect on Indigenous people

Following the Civil War, the U.S. had ratified roughly 400 treaties with the Plains tribes but went on to break much of these in pursuit of the

Once amongst the tallest people in the world, the generations of bison-reliant people born after the slaughter lost their entire height advantage. By the early twentieth century, child mortality was 16 percentage points higher and the probability of reporting an occupation 19 percentage points lower in bison nations compared with nations that were never reliant on the bison. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and into the present, income per capita has remained 25% lower, on average, for bison nations.

Loss of land

Much of the land delegated to Indigenous tribes during this westward expansion were barren tracts of land, far from any buffalo herds. These reservations were not sustainable for Natives, who relied on bison for food. One of these reservations was the Sand Creek Reservation in southeastern Colorado. The nearest buffalo herd was over two hundred miles away, and many Cheyennes began leaving the reservation, forced to hunt livestock of nearby settlers and passing wagon trains.[105]

Loss of food source

Plains Indians adopted a nomadic lifestyle, one which depended on bison location for their food source. Bison is high in protein levels and low in fat content and contributes to the wholesome diet of Native Americans. Additionally, they used every edible part of the bison—organs, brains, fetuses, and placental membranes included.[106]

Loss of autonomy

As a consequence of the great bison slaughter, they became more heavily dependent on the U.S. Government and American traders for their needs. Many military men recognized the bison slaughter as a way of reducing the autonomy of Indigenous Peoples. For instance, Lieutenant Colonel Dodge, a high-ranking military officer, once said in a conversation with Frank H. Mayer: "Mayer, there's no two ways about it, either the buffalo or the Indian must go. Only when the Indian becomes absolutely dependent on us for his every need, will we be able to handle him. He's too independent with the buffalo. But if we kill the buffalo we conquer the Indian. It seems a more humane thing to kill the buffalo than the Indian, so the buffalo must go."[107]

" The country’s highest generals, politicians, and even then President Ulysses S. Grant saw the destruction of buffalo as solution to the country’s “Indian Problem".”[108]

Even Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian School and a Tenth Cavalry lieutenant in the Red River War, discussed this strategy after his retirement: "The generation of the buffalo was ordered as a military measure because it was plain that the Indians could not be controlled on their reservations as long as their greatest resource, the buffalo, were so plentiful."[107]

The destruction of bison signaled the end of the Indian Wars, and consequently their movement towards reservations. When the Texas legislature proposed a bill to protect the bison, General Sheridan disapproved of it, stating, "These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians' commissary. It is a well-known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle."[103]

Spiritual effects

Most Native American tribes regard the bison as a sacred animal and religious symbol. University of Montana anthropology professor S. Neyooxet Greymorning stated: "The creation stories of where buffalo came from put them in a very spiritual place among many tribes. The buffalo crossed many different areas and functions, and it was utilized in many ways. It was used in ceremonies, as well as to make tipi covers that provide homes for people, utensils, shields, weapons, and parts were used for sewing with the sinew."[109] In fact, many tribes had "buffalo doctors", who claimed to have learned from bison in symbolic visions. Also, many Plains tribes used the bison skull for confessions and blessing burial sites.[110][full citation needed]

Though buffalo were being slaughtered in masses, many tribes perceived the buffalo as part of the natural world—something guaranteed to them by the Creator. For some Plains Indigenous peoples, buffalo are known as the first people.[111] Many tribes did not grasp the concept of species extinction.[112] Thus, when the buffalo began to disappear in great numbers, it was particularly harrowing to the tribes. As Crow Chief Plenty Coups described it: "When the buffalo went away, the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere."[107] Spiritual loss was rampant; buffalo were an integral part of their society and they would frequently take part in ceremonies for each buffalo they killed to honor its sacrifice. To boost morale during this time, the Sioux and other tribes took part in the Ghost Dance, which consisted of hundreds of people dancing until 100 persons were lying unconscious.[113]

Native Americans served as the caretakers of bison, so their forced movement towards bison-free reservation areas was particularly challenging. Upon their arrival to reservations, some tribes asked government officials if they could hunt cattle the way they hunted buffalo. During these cattle hunts, Plains tribes would dress up in their finery, sing bison songs, and attempt to simulate a bison hunt. These cattle hunts served as a way for the tribes to preserve their ceremonies, community, and morale. However, the U.S. government soon put a halt to cattle hunts, choosing to package the beef up for the Native Americans instead.[114]

Ecological effect

The mass buffalo slaughter also seriously harmed the ecological health of the Great Plains region, in which many Indigenous People lived. Unlike cattle, bison were naturally fit to thrive in the Great Plains environment; bison's giant heads are naturally fit to drive through snow making them far more likely to survive harsh winters.[115] Additionally, bison grazing helps to cultivate the prairie, making it ripe for hosting a diverse range of plants. Cattle, on the other hand, eat through vegetation and limit the ecosystem's ability to support a diverse range of species.[116] Agricultural and residential development of the prairie is estimated to have reduced the prairie to 0.1% of its former area.[106] The plains region has lost nearly one-third of its prime topsoil since the onset of the buffalo slaughter. Cattle are also causing water to be pillaged at rates that are depleting many aquifers of their resources.[117] Research also suggests that the absence of native grasses leads to topsoil erosion—a main contributor to the Dust Bowl and black blizzards of the 1930s.[106]

Resurgence of the bison

Beginnings of resurgence

James "Scotty" Philip

The famous herd of James "Scotty" Philip in South Dakota was one of the earliest reintroductions of bison to North America. In 1899, Philip purchased a small herd (five of them, including the female) from Dug Carlin, Pete Dupree's brother-in-law, whose son Fred had roped five calves in the Last Big Buffalo Hunt on the Grand River in 1881 and taken them back home to the ranch on the Cheyenne River. Scotty's goal was to preserve the animal from extinction. At the time of his death in 1911 at 53, Philip had grown the herd to an estimated 1,000 to 1,200 head of bison. A variety of privately owned herds had also been established, starting from this population.

Michel Pablo & Charles Allard

In 1873, Samuel Walking Coyote, a member of the Pend d'orville tribe, herded seven orphan calves along the Flathead Reservation west of the Rocky Mountain divide. In 1899, he sold 13 of these bison to ranchers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo for $2,000 in gold.[119] Michel Pablo and Charles Allard spent more than 20 years assembling one of the largest collections of purebred bison on the continent (by the time of Allard's death in 1896, the herd numbered 300). In 1907, after U.S. authorities declined to buy the herd, Pablo struck a deal with the Canadian government and shipped most of his bison northward to the newly created Elk Island National Park.[93][120]

Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge

Also, in 1907, the New York Zoological Park sent 15 bison to Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma forming the nucleus of a herd that now numbers 650.[121]

Yellowstone Park

The

Antelope Island

The

Molly Goodnight

The last of the remaining "southern herd" in Texas were saved before extinction in 1876.

Austin Corbin

In 1904 the naturalist Ernest Harold Baynes (1868–1925) was appointed conservator of the Corbin Park game reserve in New Hampshire (on the edge of the Blue Mountain Forest), by Austin Corbin, Jr. (d.1938), whose father, the banker and railroad entrepreneur Austin Corbin (1827–1896) had established it.[125] Known as the "Blue Mountain Forest Association", it was a limited membership proprietary hunting club, the park for which comprised 26,000 acres, covering the townships of Cornish, Croydon, Grantham, Newport, and Plainfield.

Corbin Sr. imported

Baynes was famous for his tame bison, and for driving around the park in a carriage pulled by a pair of bison. Amongst his published works is War Whoop and Tomahawk: The Story of Two Buffalo Calves (1929). Baynes commented:

"Of all the works of the late Mr. Austin Corbin, the preservation of that herd of bison was the one that would earn his country’s deepest gratitude. His experiment led to the founding of the American Bison Society and was connected, directly or otherwise, with the formation of some of our national parks".[128]

Modern bison resurgence efforts

Many other bison herds are in the process of being created or have been created in

One of the largest privately owned herds, numbering 2,500, in the US, is on the

The current American bison population has been growing rapidly and is estimated at 350,000 compared to an estimated 60 to 100 million in the mid-19th century.[citation needed] Most current herds, however, are genetically polluted or partly crossbred with cattle.[133][134][135][136] Today there are only four genetically unmixed, free-roaming, public bison herds and only two that are also free of brucellosis: the Henry Mountains bison herd and the Wind Cave bison herd. A founder population of 16 animals from the Wind Cave bison herd was re-established in Montana in 2005 by the American Prairie Foundation. The herd now numbers nearly 800 and roams a 14,000-acre (57 km2) grassland expanse on American Prairie.

The end of the ranching era and the onset of the natural regulation era set into motion a chain of events that have led to the bison of Yellowstone Park migrating to lower elevations outside the park in search of winter forage. The presence of wild bison in Montana is perceived as a threat to many cattle ranchers, who fear that the small percentage of bison that carry brucellosis will infect livestock and cause cows to abort their first calves. However, there has never been a documented case of brucellosis being transmitted to cattle from wild bison. The management controversy that began in the early 1980s continues with advocacy groups arguing that the herd should be protected as a distinct population segment under the

Native American bison conservation efforts

Many conservation measures have been taken by Native American tribes to preserve and grow the bison population as well. Of these Native conservation efforts, the Inter-Tribal Bison Council was formed in 1990, composed of 56 tribes in 19 states.[137] These tribes represent a collective herd of more than 15,000 bison and focus on reestablishing herds on tribal lands to promote culture, revitalize spiritual solidarity, and restore the ecosystem. Some Inter-Tribal Bison Council members argue that the bison's economic value is one of the main factors driving its resurgence. Bison serves as a low-cost substitute for cattle and can withstand the winters in the Plains region far easier than cattle.[137]

A Native American conservation effort that has been gaining ground is the Buffalo Field Campaign. Founded in 1996 by Mike Mease, Sicango Lakota, and Rosalie Little Thunder, the Buffalo Field Campaign hopes to get bison migrating freely in Montana and beyond. The Buffalo Field Campaign challenges Montana's DOL officials, who slaughtered 1631 bison in the winter of 2007-2008 in a food search away from Yellowstone National Park. Founder Mike Mease commented in regards to DOL officials: "It's disheartening what they're doing to buffalo. It's marked with prejudice that exists from way back. I think the whole problem with white society is there's this fear of anything wild. They're so scared of anything they can't control, whereas the First Nations take pride in being part of it and protecting the wild because of its importance. Our culture is so far removed from that, and afraid of it."[138]

Additionally, many smaller tribal groups aim to reintroduce bison to their native lands. The Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, which was restored in 1990, has a herd of roughly 100 bison in two pastures. Similarly, the Southern Ute Tribe in Colorado has raised nearly 30 bison in a 350-acre fenced pasture.[139]

According to Rutgers University Professor Frank Popper, bison restoration brings better meat and ecological health to the plains region, in addition to restoring bison-native American relations. However, there is a considerable risk involved with restoring the bison population: brucellosis. If bison are introduced in large numbers, the risk of brucellosis is high.[137]

Bison conservation: a symbol of Native American healing

For some spokesmen, the resurgence of the bison population reflects a cultural and spiritual recovery from the effects of bison hunting in the mid-1800s. By creating groups such as the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative and the Buffalo Field Campaign, Native Americans are hoping to not only restore the bison population but also improve solidarity and morale among their tribes. "We recognize the bison as a symbol of strength in unity," stated Fred Dubray, former president of the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative. "We believe that reintroduction of the buffalo to tribal lands will help heal the spirit of both the Indian people and the buffalo. To reestablish healthy buffalo populations is to reestablish hope for Indian people."[140]

Modern hunting

Hunting of wild bison is legal in some states and provinces where public herds require culling to maintain a target population.

Canada

Alberta

In Alberta, where one of only two continuously wild herds of bison exist in North America at Wood Buffalo National Park, bison are hunted to protect disease-free public (reintroduced) and private herds of bison.[citation needed]

United States

Montana

In Montana, a public hunt was reestablished in 2005, with 50 permits being issued. The Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Commission increased the number of tags to 140 for the 2006/2007 season. Advocacy groups claim that it is premature to reestablish the hunt, given the bison's lack of habitat and wildlife status in Montana.[citation needed]

Though the number is usually several hundred, up to more than a thousand bison from the

Utah

The

Every year all the bison in the

Hunting is also allowed every year in the Henry Mountains bison herd in Utah. The Henry Mountains herd has sometimes numbered up to 500 individuals but the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources has determined that the carrying capacity for the Henry Mountains bison herd is 325 individuals. Some of the extra individuals have been transplanted, but most of them are not transplanted or sold, so hunting is the major tool used to control their population. "In 2009, 146 public once-in-a-lifetime Henry Mountain bison hunting permits were issued."[142] Most years, 50 to 100 licenses are issued to hunt bison in the Henry Mountains.[citation needed]

Alaska

Bison were also reintroduced to Alaska in 1928, and both domestic and wild herds are found in a few parts of the state.[143][144] The state grants limited permits to hunt wild bison each year.[145][146]

Mexico

In 2001, the United States government donated some bison calves from South Dakota and Colorado to the Mexican government for the reintroduction of bison to Mexico's nature reserves. These reserves included El Uno Ranch at Janos and Santa Elena Canyon, Chihuahua, and Boquillas del Carmen, Coahuila, which are located on the southern shore of the Rio Grande and the grasslands bordering Texas and New Mexico.[147]

See also

References

- .

- ISSN 0002-7316.

- ^ Castaneda, Pedro (1966). The Journey of Coronado. Ann Arbor, p. 205.

- JSTOR 2561275.

- ^ Juras, Philip (1997). "The Presettlement Piedmont Savanna: A Model For Landscape Design and Management". Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Sheppard Software, Bison

- ^ a b Fletcher, Alice C. and F. La Flesche (1992). The Omaha Tribe. Lincoln and London, p. 281.

- ^ Murie, James R. (1981): "Ceremonies of the Pawnee. Part I: The Skiri Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, No. 27, p. 98.

- ^ a b Krech III, Shepard. "Buffalo Tales: The Near-Extermination of the American Bison". National Humanities Center. Brown University. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Ewers, John C. (1988): "The last Bison Drive of the Blackfoot Indians". Indian Life On The Upper Missouri. Norman and London, pp. 157–168.

- ^ Medicine Crow, Joseph (1992): From the Heart of the Crow Country. The Crow Indians' Own Stories. New York, pp. 86–99.

- ^ Lowie, Robert H. (1983): The Crow Indians. Lincoln and London, p. 73.

- ^ Ewers, John C. (1988): "A Blood Indian's Conception of Tribal Life in Dog Days". Indian Life On The Upper Missouri. Norman and London, p. 9.

- ^ Kelsey, Henry (1929): The Kelsey Papers. Ottawa, p. 13.

- )

- ^ Wood, Raymond W. and Thomas D. Thiessen (1987): Early Fur Trade On The Northern Plains. Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818. Norman and London, p. 265.

- ^ Wood, Raymond W. and Thomas D. Thiessen (1987): Early Fur Trade On The Northern Plains. Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818. Norman and London, p. 239.

- ^ Castaneda (1966), p. 112.

- ^ Hyde, George E. (1987): Life of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman, p. 12.

- S2CID 131061213.

- ^ Mallory, Gerrick (1886): "The Corbusier Winter Counts Smithsonian Institution. 4th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1882–83. Washington, p. 136.

- ^ Nabokov, Peter (1982): Two Leggings. The Making of a Crow Warrior. Lincoln and London, p. 158.

- ^ Murray, Charles A. (1974): Travels in North America. Vol. I. New York, p. 386.

- ^ Chardon, F. A. (1997): Chardon's Journal at Fort Clark, 1834–1839. Lincoln and London, p. 159.

- ^ Boyd, Maurice (1981): Kiowa Voices. Ceremonial Dance, Ritual and Song. Part I. Fort Worth, p. 15.

- ^ Hyde, George E. (1987): Life of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman, p. 200.

- ^ Walker, James R. (1982): Lakota Society. Lincoln and London, p. 40.

- ^ Fletcher & La Flesche (1992), p. 272.

- ^ Densmore, Frances (1918): Teton Sioux Music. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 61. Washington, p. 439.

- ^ Castaneda (1966), p. 71.

- ^ Blaine, Martha R. (1990): Pawnee Passage, 1870–1875. Norman and London, p. 81.

- ^ Walker, James R. (1982): Lakota Society. Lincoln and London, p. 80.

- ^ Murray, Charles A. (1974): Travels in North America. Vol. I. New York, p. 297.

- ^ Boyd, Maurice (1983): Kiowa Voices. Myth, Legends and Folktales. Part II. Fort Worth, p. 127.

- ^ Fletcher & La Flesche (1992), p. 148.

- ^ Tableau, Pierre-Antoine (1968): Tableau's Narrative of Loisel's Expedition to the Upper Missouri. Norman, p. 72.

- ^ Chardon, F. A. (1997): Chardon's Journal At Fort Clark, 1834–1839. Lincoln and London, p. 52.

- ^ Castaneda (1966), p. 210.

- ^ McGinnis, Anthony (1990): Counting Coup and Cutting Horses. Evergreen.

- ^ Ewers, John C. (Oct. 1975): "Intertribal Warfare as a Precursor of Indian-White Warfare on the Northern Great Plains". Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 397-410.

- ^ Hyde, George E. (1987): Life of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman, p. 16.

- ^ Meyer, Roy W. (1977): The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri. The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras. Lincoln and London, p. 40.

- ^ Boyd, Maurice (1983): Kiowa Voices. Myth, Legends and Folktales. Part II. Fort Worth, p. 79.

- ^ Boyd, Maurice (1983): Kiowa Voices. Myth, Legends and Folktales. Part II. Fort Worth, p. xxvi.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (April 1982): "The Inter-tribal Balance of Power on the Great Plains, 1760–1850". The Journal of American Studies, Vol. 16., No. 1, pp. 25–47, p. 40.

- ^ Farr, William E. (Winter 2003): "Going to Buffalo. Indian Hunting Migrations across the Rocky Mountains. Part 1". Montana, the Magazine of Western History, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 2–21, p. 6.

- ^ Boas, Franz (1918): Kutenai Tales. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 59. Washington, p. 53.

- ^ U.S. Serial Set 1284, 39th Congress, 2nd Session, Vol. 2, House Executive Document No. 1, p. 315.

- ^ McGinnis, Anthony (1990): Counting Coup and Cutting Horses. Evergreen, p. 122.

- ^ Howard, James H. (1965) "The Ponca Tribe". Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 195. Washington, p. 30.

- ^ McGinnis, Anthony (1990): Counting Coup and Cutting Horses. Evergreen, p. 97.

- ^ Meyer (1977), p. 108.

- ^ a b Hyde, George E. (1987): Life of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman, p. 26.

- ^ Paul, Eli R. (1997): Autobiography of Red Cloud. War Leader of the Oglalas. Chelsea, pp. 136–140

- ^ Boller, Henry A. (1966): "Henry A. Boller: Upper Missouri River Fur Trader". North Dakota History, Vol. 33, pp. 106–219, 204.

- ^ Bowers, Alfred W. (1991): Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization. Moscow, p. 177.

- ^ Blaine, Garland James an Martha Royce Blaine (1977): "Pa-Re-Su A-Ri-Ra-Ke: The Hunters that were Massacred". Nebraska History, Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 342-358.

- ^ Standing Bear, Luther (1975): My People, the Sioux. Lincoln, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Bowers, Alfred W. (1991): Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization. Moscow, p. 360.

- ^ Stewart, Frank H. (Nov. 1974): "Mandan and Hidatsa Villages in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 19, pp. 287–302, p. 296.

- ^ Meyer (1977), p. 97.

- ^ Meyer (1977), p. 119.

- ^ Meyer (1977), pp. 105–106.

- ^ Howard (1965), p. 27.

- ^ Howard (1965), p. 31.

- ^ Jensen, Richard E. (Winter 1994): "The Pawnee Mission, 1834-1846". Nebraska History, Vol. 75, No. 4, pp. 301–310, p. 307.

- ^ Bedford, Denton R. (1975): "The Fight at "Mountains on Both Sides". The Indian Historian, Vol. 8. No. 2, pp. 13–23, p. 22.

- ^ Scherer, Joanna Cohan (Fall 1997): "The 1852 Omaha Indian Delegation Daguerreotypes. A Preponderance of Evidence". Nebraska History Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 116–121. p. 118.

- ^ S2CID 154413490.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8061-2694-4.

- OCLC 1112113. Archived from the originalon April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ "In the Prime of the Buffalo". Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine. 14 (83): 515. November 1889.

- ISBN 978-0521771726.

- ^ "American Buffalo: Spirit of a Nation". NPT. PBS. November 10, 1998. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ JSTOR 971110. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 6, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Wooster, Robert (1988). "The Military and United States Indian Policy 1865-1903". ICE Case Studies: The Buffalo Harvest. Yale University Press. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Hanson, Emma I. Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian People. Cody, WY: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 2007: 211.

- ^ Moulton, M (1995). Wildlife issues in a changing world, 2nd edition. CRC Press.

- ^ JSTOR 971110. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "John M. Schofield, Forty-six years in the Army, Chapter XXIII, page 428". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ "On This Day: June 6, 1874". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ "Page:U.S. Department of the Interior Annual Report 1873.djvu/8 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- ^ King, Gilbert (July 17, 2012). "Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Value of the Buffalo to Man",

- ^ Page 9 T. Lindsay Baker, Billy R. Harrison, B. Byron Price, Adobe Walls

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (1961): The Assiniboine. Norman, p. LVII.

- ^ Gilman, Carolyn and M. J. Schneider (1987): The Way to Independence. Memories of a Hidatsa Indian Family, 1840–1920. St. Paul, p. 228.

- ^ Fowler, Loretta (1987): Shared Symbols, Contested Meanings. Gros Ventre Culture and History, 1778–1984. Ithaca and London, p. 67.

- ^ Fletcher & La Flesche (1992), p. 51.

- ^ Fletcher & La Flesche (1992), p. 33.

- ^ a b Bergman, Brian (February 16, 2004). "Bison Back from Brink of Extinction". Maclean's. Retrieved March 14, 2008 – via Canadian Encyclopedia.

For the sake of lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated.

- ISBN 978-0-89781-055-5.

- ^ Patten, James I. (January–March 1993): "Last Great Hunt of Washakie and his Band". Wind River Mountaineer. Fremont County's Own History Magazine, Vol. IX, No. 1, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Gilmore, Melvin R. (1931): "Methods of Indian Buffalo Hunts, with the Itinerary of the Last Tribal Hunt of the Omaha". Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts & Letters, Vol. 14, pp. 17–32.

- ^ Fox, Gregory L. (1988): A Late Nineteenth Century Village of a Band of Dissident Hidatsa: The Garden Coulee Site (32WI18). Lincoln.

- ^ Farr, William E. (Spring 2004): "Going to Buffalo. Indian Hunting Migrations across the Rocky Mountains. Part 2". Montana, the Magazine of Western History, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 26–43. pp. 39 and 41.

- ^ Farr, William E. (Spring 2004): "Going to Buffalo. Indian Hunting Migrations across the Rocky Mountains. Part 2". Montana, the Magazine of Western History, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 26–43. p. 43.

- ^ Fowler, Loretta (1987): Shared Symbols, Contested Meanings. Gros Ventre Culture and History, 1778–1984. Ithaca and London, p. 33.

- ^ Fowler, Loretta (1987): Shared Symbols, Contested Meanings. Gros Ventre Culture and History, 1778–1984. Ithaca and London, p. 63.

- ^ Ostler, Jeffrey (Spring 2001): "'The Last Buffalo Hunt' And Beyond. Plains Sioux Economic Strategies In The Early Reservation Period". Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2, p. 115.

- ^ a b King, Gilbert (July 17, 2012). "Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ISSN 0034-6527.

- ^ "Black Kettle". New Perspectives on The West. PBS. 2001. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b c Duval, Clay. "Bison Conservation: Saving an Ecologically and Culturally Keystone Species" (PDF). Duke University. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ JSTOR 971110. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 6, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Phippen, J. Weston (May 13, 2016). ""Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone"". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Jawort, Adrian (May 9, 2011). "Genocide by Other Means: U.S. Army Slaughtered Buffalo in Plains Indian Wars". Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Duval, Clay. "Bison Conservation: Saving an Ecologically and Culturally Keystone Species". Duke University. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-5779-7.

- ISBN 978-1588344786.

- ^ Parker, Z. A. (1890). "The Ghost Dance Among the Lakota". PBS Archives of the West. PBS. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Jawart, Adrian (May 9, 2011). "Genocide by Other Means: U.S. Army Slaughtered Buffalo in Plains Indian Wars". indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2011/05/09/genocide-other-means-us-army-sl. Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0896085992. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0896085992. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0896085992. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Ley, Willy (December 1964). "The Rarest Animals". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- S2CID 131061213.

- ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ American Bison, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Staff (December 2011 – January 2012). "Restoring a Prairie Icon". National Wildlife. 50 (1). National Wildlife Federation: 20–25.

- ^ John Cornyn, The Winkler Post, Molly Goodnight [1] Archived June 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine

- ^ a b "The Birds' Best Friend: How Ernest Baynes Saved the Animals". August 29, 2013.

- ^ Kronenwetter

- ^ Mary T. Kronenwetter, Corbin’s “Animal Garden”

- ^ Quoted in Kronenwetter

- ^ National Bison Range – Dept of the Interior Recovery Activities Archived February 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Recovery.doi.gov. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ American Bison Society > Home Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Americanbisonsocietyonline.org. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ "Where the Buffalo Roam". Mother Jones. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ "Ranches". Tedturner.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (January 19, 2007). "Strands of undesirable DNA roam with buffalo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- JSTOR 2387208.

- S2CID 4501193. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 10, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- hdl:1969.1/1415. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Patel, Moneil (June 1997). "Restoration of Bison onto the American Prairie". UC Irving. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Jawort, Adrian (May 9, 2011). "Genocide by Other Means: U.S. Army Slaughtered Buffalo in Plains Indian Wars". Indian Country Today. Indian Country Today. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "American Bison and American Indian Nations". Smithsonian Institution National Zoo. Smithsonian. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "American Buffalo: Spirit of a Nation". NPT. PBS. November 10, 1998. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- PMID 22427502.

- ^ "Once-In-A-Lifetime Permits" (PDF). Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2010.

- ^ "Alaska Hunting and Trapping Information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Wc.adfg.state.ak.us. Archived from the original on August 21, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska Hunting and Trapping Information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Wc.adfg.state.ak.us. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Adfg.state.ak.us. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska bison hunt near Delta Junction". Outdoorsdirectory.com. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ staff (March 3, 2010). "Restoring North America's Wild Bison to Their Home on the Range". Ens-newswire.com. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

Further reading

- Branch, E. Douglas. The Hunting of the Buffalo (1929, new ed. University of Nebraska Press, 1997), classic history online edition Archived June 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Barsness, Larry. Heads, Hides and Horns: The Compleat Buffalo Book. (Texas Christian University Press, 1974)

- Dary David A. The Buffalo Book. (Chicago: Swallow Press, 1974)

- Dobak, William A. (1996). "Killing the Canadian Buffalo, 1821–1881". Western Historical Quarterly. 27 (1): 33–52. JSTOR 969920.

- Dobak, William A. (1995). "The Army and the Buffalo: A Demur". Western Historical Quarterly. 26 (2): 197–203. JSTOR 970189.

- Flores, Dan (1991). "Bison Ecology and Bison Diplomacy: The Southern Plains from 1800 to 1850". Journal of American History. 78 (2): 465–85. JSTOR 2079530.

- Gard, Wayne. The Great Buffalo Hunt (University of Nebraska Press, 1954)

- Isenberg, Andrew C. (1992). "Toward a Policy of Destruction: Buffaloes, Law, and the Market, 1803–1883". Great Plains Quarterly. 12: 227–41.

- Isenberg, Andrew C. The Destruction of the Buffalo: An Environmental History, 1750–1920 (Cambridge University press, 2000) online edition

- Koucky, Rudolph W. (1983). "The Buffalo Disaster of 1882". North Dakota History. 50 (1): 23–30. PMID 11620389.

- McHugh, Tom. The Time of the Buffalo (University of Nebraska Press, 1972).

- Meagher, Margaret Mary. The Bison of Yellowstone National Park. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1973)

- Punke, Michael. Last Stand: George Bird Grinnell, the Battle to Save the Buffalo, and the Birth of the New West (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. xvi, 286 pp. ISBN 978-0-8032-2680-7

- Rister, Carl Coke (1929). "The Significance of the Destruction of the Buffalo in the Southwest". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 33 (1): 34–49. JSTOR 30237207.

- Roe, Frank Gilbert. The North American Buffalo: A Critical Study of the Species in Its Wild State (University of Toronto Press, 1951).

- Shaw, James H. (1995). "How Many Bison Originally Populated Western Rangelands?". Rangelands. 17 (5): 148–150. JSTOR 4001099.

- Smits, David D. (1994). "The Frontier Army and the Destruction of the Buffalo, 1865–1883" (PDF). Western Historical Quarterly. 25 (3): 313–38. JSTOR 971110. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011. and 26 (1995) 203-8.

- Zontek, Ken (1995). "Hunt, Capture, Raise, Increase: The People Who Saved the Bison". Great Plains Quarterly. 15: 133–49.

- Laduke, Winona. "All of Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life" (South End Press, 1999)