Cannabis

| Cannabis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common hemp | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis L. |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabis (

The plant is also known as

Description

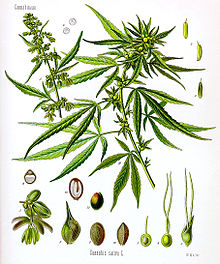

Cannabis is an

The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic venation pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of cannabis leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in cannabis this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of Cannabis also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.[12]

Reproduction

All known

Cannabis is predominantly

Many monoecious varieties have also been described,[20] in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.[21] (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in Cannabis – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.[22][23][24] Many populations have been described as sexually labile.[25][26][27]

As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, Cannabis exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.[28] Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,[22] but sativa strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of inbreeding.

Sex determination

Cannabis has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of sex determination among the dioecious plants.[28] Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in Cannabis.

Based on studies of sex reversal in

Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.[15] Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.[31]

Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for Cannabis. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".[15]

The question of whether heteromorphic

More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors[35][36] have used random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) to isolate several genetic marker sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and amplified fragment length polymorphism.[37][25][38] Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating,

It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.[15]

Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.

-

A male hemp plant

-

Dense raceme of female flowers typical of drug-type varieties of Cannabis

Chemistry

Cannabis plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their defense against herbivory. One group of these is called cannabinoids, which induce mental and physical effects when consumed.

Cannabinoids, terpenes, terpenoids, and other compounds are secreted by glandular trichomes that occur most abundantly on the floral calyxes and bracts of female plants.[42]

-

Root system side view

-

Root system top view

-

Micrograph C. sativa (left), C. indica (right)

Genetics

Cannabis, like many organisms, is

Taxonomy

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as

- plants cultivated for fiber and seed production, described as low-intoxicant, non-drug, or fiber types.

- plants cultivated for drug production, described as high-intoxicant or drug types.

- escaped, hybridised, or wild forms of either of the above types.

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[49] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[50] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[51] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[52] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[37] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[52][53]

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[54] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[55] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[55] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[43] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[56] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[57][58][59]

Early classifications

The genus Cannabis was first

20th century

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[66] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies and two varieties in each. The framework is thus:

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa, presumably selectedfor traits that enhance fiber or seed production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. sativa, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. spontanea Vav., wild or escaped variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica (Lam.) Small & Cronq.,[62] primarily selected for drug production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica var. indica, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa subsp. indica var. kafiristanica (Vav.) Small & Cronq, wild or escaped variety.

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist

Continuing research

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[80]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[81] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018[update]) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[82]

Popular usage

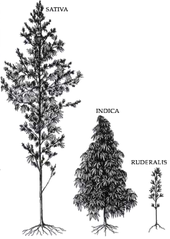

The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type Cannabis. Cannabis aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology,

Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. indica var. indica, "Indica" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. i. kafiristanica (also known as afghanica), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into C. sativa subsp. sativa. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.[74] Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results.

Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type Cannabis often describe the ancestry or gross phenotypic characteristics of cultivars by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.[74]

Phylogeny

Cannabis likely split from its closest relative, Humulus (hops), during the mid Oligocene, around 27.8 million years ago according to molecular clock estimates. The centre of origin of Cannabis is likely in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. The pollen of Humulus and Cannabis are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from Cannabis is from Ningxia, China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, dating to the early Miocene, around 19.6 million years ago. Cannabis was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known Cannabis in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.[83]

Etymology

The word cannabis is from Greek κάνναβις (kánnabis) (see Latin cannabis),[84] which was originally Scythian or Thracian.[85] It is related to the Persian kanab, the English canvas and possibly the English hemp (Old English hænep).[85]

Uses

Cannabis is used for a wide variety of purposes.

History

According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period.[9] The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.[86] The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian Herodotus's reference to the central Eurasian Scythians taking cannabis steam baths.[87] His (c. 440 BCE) Histories records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed [presumably, flowers], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."[88] Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis.

In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the

In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.[90][91][92][93]

Cannabinol (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.[94]

Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis

Recreational use

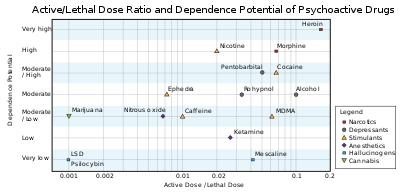

Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.[when?][97] As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried infructescences ("buds" or "marijuana"), resin (hashish), or various extracts collectively known as hash oil.[10]

Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a

Cannabidiol (CBD), which has no intoxicating effects by itself[51] (although sometimes showing a small stimulant effect, similar to caffeine),[99] is thought to attenuate (i.e., reduce)[100] the anxiety-inducing effects of high doses of THC, particularly if administered orally prior to THC exposure.[101]

According to

In 2014 there were an estimated 182.5 million cannabis users worldwide (3.8% of the global population aged 15–64).[107] This percentage did not change significantly between 1998 and 2014.[107]

Medical use

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, in an effort to treat disease or improve symptoms. Cannabis is used to

Short-term use increases both minor and major adverse effects.[109] Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, vomiting, and hallucinations.[109] Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear.[113] Concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, schizophrenia in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.[108]

Industrial use (hemp)

The term hemp is used to name the durable soft fiber from the Cannabis

Cannabis for industrial uses is valuable in tens of thousands of commercial products, especially as fibre

In the US, "industrial hemp" is classified by the federal government as cannabis containing no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. This classification was established in the

Ancient and religious uses

The Cannabis plant has a history of medicinal use dating back thousands of years across many cultures.

Settlements which date from c. 2200–1700 BCE in the

: 306Cannabis is first referred to in

In

In modern times, the

Since the 13th century CE, cannabis has been used among

See also

- All pages with titles beginning with Cannabis

- All pages with titles containing Cannabis

- Cannabis drug testing

- Cannabis edible

- Cannabis flower essential oil

- Hash, Marihuana & Hemp Museum

- Indian Hemp Drugs Commission

- Legal history of cannabis in the United States

- Legality of cannabis by U.S. jurisdiction

- List of books about cannabis

- Occupational health concerns of cannabis use

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85369-517-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-3635-5. Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Classification Report". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Indica, Sativa, Ruderalis – Did We Get It All Wrong?". The Leaf Online. 26 January 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Species of Cannabis". GRIN Taxonomy. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Cannabis sativa L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-58829-456-2. Archivedfrom the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-3-906390-56-7. Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ PMID 34272249.

- ^ a b Erowid. 2006. Cannabis Basics. Archived 23 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 25 February 2007.

- ^ "Leaf Terminology (Part 1)". Waynesword.palomar.edu. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Watt JM, Breyer-Brandwijk MG (1962). The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa (2nd ed.). E & S Livingstone.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-914171-78-2.[page needed]

- doi:10.1139/b75-117.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ Hui-Lin L (1973). "The Origin and Use of Cannabis in Eastern Asia: Linguistic-Cultural Implications". Economic Botany. 28 (3): 293–301 (294).

- ^ 13/99 and 13/133. In addition, 13/98 defined fen 蕡 "Cannabis inflorescence" and 13/159 bo 薜 "wild Cannabis".

- ^ Bouquet, R. J. 1950. Cannabis. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved on 23 February 2007

- ISBN 978-1-56022-872-1.

- S2CID 11835610.

- ^ a b Mignoni G (1 December 1999). "Cannabis as a licit crop: recent developments in Europe". Global Hemp. Archived from the original on 13 March 2003. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- S2CID 34246180.

- S2CID 26214647.

- ^ S2CID 84960806.

- ^ a b Hirata K (1924). "Sex reversal in hemp". Journal of the Society of Agriculture and Forestry. 16: 145–168.

- ^ JSTOR 2435878.

- ^ PMID 12441630.

- S2CID 84528876.

- hdl:1811/2398.

- PMID 11743084.

- JSTOR 2483524.

- ^ Hong S, Clarke RC (1996). "Taxonomic studies of Cannabis in China". Journal of the International Hemp Association. 3 (2): 55–60. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- S2CID 11453369.

- PMID 8589931.

- S2CID 40436657.

- ^ PMID 12586720.

- S2CID 27065456.

- PMID 15084718.

- S2CID 12256760.

- S2CID 84460585.

- ^ Mahlberg PG, Eun SK (2001). "THC (tetrahyrdocannabinol) accumulation in glands of Cannabis (Cannabaceae)". The Hemp Report. 3 (17). Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ doi:10.1139/b72-248.

- PMID 22014239.

- ISBN 978-0-89281-979-9.

- S2CID 45337406.

- S2CID 207690258.

- ^ PMID 1041693.

- ^ "What chemicals are in marijuana and its byproducts?". ProCon.org. 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- PMID 20332000.

- ^ from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ PMID 4744553.

- ^ S2CID 32469533.

- ISBN 978-0-919217-11-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-52054-4.

- ^ S2CID 24866870.

- ^ a b Small E (1975). "On toadstool soup and legal species of marihuana". Plant Science Bulletin. 21 (3): 34–9. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ^ PMID 7024491.

- ISBN 978-0-398-03863-2.

- ^ Linnaeus C (1957–1959) [1753]. Species Plantarum. Vol. 2 (Facsimile ed.). Ray SocietyLondon, U.K. (originally Salvius, Stockholm). p. 1027.

- ^ de Lamarck JB (1785). Encyclopédie Méthodique de Botanique. Vol. 1. Paris, France. pp. 694–695.

- ^ JSTOR 1220524.

- PMID 322936.

- ^ Serebriakova TY, Sizov IA (1940). "Cannabinaceae Lindl.". In Vavilov NI (ed.). Kulturnaya Flora SSSR (in Russian). Vol. 5. Moscow-Leningrad, USSR. pp. 1–53.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - PMID 16424501.

- ^ Ernest Small (biography) Archived 11 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. National Research Council Canada. Retrieved on 23 February 2007

- JSTOR 2418840.

- doi:10.5962/p.168565.

- ^ Anderson, L. C. Archived 8 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine 1974. A study of systematic wood anatomy in Cannabis. Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets 24: 29–36. Retrieved on 23 February 2007

- ^ Anderson, L. C. Archived 8 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine 1980. Leaf variation among Cannabis species from a controlled garden. Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets 28: 61–69. Retrieved on 23 February 2007

- S2CID 35358047.

- ^ Schultes RE (1970). "Random thoughts and queries on the botany of Cannabis". In Joyce CR, Curry SH (eds.). The Botany and Chemistry of Cannabis. London: J. & A. Churchill. pp. 11–38.

- ^ Interview with Robert Connell Clarke. 1 January 2005. NORML, New Zealand. Retrieved on 19 February 2007

- ^ PMID 30426073.

- S2CID 26011527.

- (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2022.

- PMID 12505473.

- S2CID 260280872.

- .

- PMID 33526123.

- PMID 26308334.)

- ^ "Will Craft Cannabis Growers in Canada Succeed Like Craft Brewers?". Licensed Producers Canada. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "cannabis" OED Online. July 2009. Oxford University Press. 2009. [1]

- ^ a b "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2004. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Abel E (1980). Marijuana, The First 12,000 years. New York: Plenum Press.

- .

- ^ Herodotus (1994–2009). "The History of Herodotus". The Internet Classics Archive. Translated by Rawlinson G. Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-92746-8.

- ^ "Cannabis: History". deamuseum.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-9639754-1-6.

- ISBN 1-878125-00-1.

- ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5.

- PMID 16402100.

- ISBN 9789210481571. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Drug Toxicity". Web.cgu.edu. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Introduction". NORML. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ a b Cannabis. "Erowid Cannabis (Marijuana) Vault : Effects". Erowid.org. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- S2CID 29421694.

- S2CID 4842545.

- PMID 19124693.

- S2CID 5903121.

- ^ "Marijuana Detection Times Influenced By Stress, Dieting". NORML. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Cannabis use and panic disorder". Cannabis.net. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Myths and Facts About Marijuana". Drugpolicy.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- PMID 28644037.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-1-057862-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ S2CID 8503107.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- PMID 25492113.

- PMID 31672337.

- ^ "Is marijuana safe and effective as medicine?". US National Institute on Drug Abuse. 1 July 2020. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- PMID 18559804.

- ^ a b "Hemp Facts". Naihc.org. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "The cultivation and use of hemp in ancient China". Hempfood.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Van Roekel GJ (1994). "Hemp Pulp and Paper Production". Journal of the International Hemp Association. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Atkinson G (2011). "Industrial Hemp Production in Alberta". CA: Government of Alberta, Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "7 U.S. Code § 5940 – Legitimacy of industrial hemp research". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- PMID 16540272. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 May 2010.

- ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2.

- PMID 19036842.

- PMID 31206023.

- ^ Donahue MZ (14 June 2019). "Earliest evidence for cannabis smoking discovered in ancient tombs". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- ^ Abel EL (1980). "Marijuana – The First Twelve Thousand Years". Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2009. Chapter 1: Cannabis in the Ancient World. India: The First Marijuana-Oriented Culture.

- ^ Murdoch J (1 January 1865). Classified Catalogue of Tamil Printed Books: With Introductory Notices. Christian vernacular education society. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-105-91788-2. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2020.[self-published source]

- ISBN 9789352065523. Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Pillai MS (1 January 1904). A Primer of Tamil Literature. Ananda Press. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-84340-310-4.

- ^ Vindheim JB. "The History of Hemp in Norway". The Journal of Industrial Hemp. International Hemp Association. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-940118-35-5.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-0-435-98650-6.

- ^ The Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church. "Marijuana and the Bible". Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ "Zion Light Ministry". Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-9629872-2-9.

- ^ "The Hawai'i Cannabis Ministry". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ "Cantheism". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ "Cannabis Assembly". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4422-7192-0.

- ISBN 978-0-313-20721-1.

- ^ Chapple A (17 February 2017). "Music, Dancing, And Tolerance -- Pakistan's Embattled Sufi Minority". RFERL. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

During the festival the air is heavy with drumbeats, chanting and cannabis smoke.

- ISBN 978-1-107-03175-3.

Further reading

- Deitch R (2003). Hemp: American History Revisited: The Plant with a Divided History. Algora Pub. ISBN 978-0-87586-206-4.

- Earleywine M (2005). Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513893-1. Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Emmett D, Nice G (2009). What you need to know about cannabis: understanding the facts. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-697-5. Archivedfrom the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson P (2004). The medicinal uses of cannabis and cannabinoids. Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-517-2. Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Holland J (2010). The Pot Book: A Complete Guide to Cannabis: Its Role in Medicine, Politics, science, and culture. Park Street Press. ISBN 978-1-59477-368-6. Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Iversen LL (2008). The science of marijuana (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532824-0.

- Jenkins R (2006). Cannabis and Young People: Reviewing the Evidence. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-398-1.

- Lambert DM (2008). Cannabinoids in Nature and Medicine. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-906390-56-7. Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Roffman RA, Stephens RS (2006). Cannabis Dependence: Its Nature, Consequences, and Treatment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81447-8. Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Russo E, Dreher MC, Mathre ML (2004). Women and Cannabis: Medicine, Science, and Sociology. Haworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-2101-4. Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Solowij N (1998). Cannabis and Cognitive Functioning. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59114-0. Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.