German art

German art has a long and distinguished tradition in the visual arts, from the earliest known work of figurative art to its current output of contemporary art.

Germany has only been united into a single state since the 19th century, and defining its borders has been a notoriously difficult and painful process. For earlier periods German art often effectively includes that produced in German-speaking regions including Austria, Alsace and much of Switzerland, as well as largely German-speaking cities or regions to the east of the modern German borders.

Although tending to be neglected relative to Italian and French contributions from the point of view of the

The

Prehistory to Late Antiquity

The area of modern Germany is rich in finds of prehistoric art, including the Venus of Hohle Fels. This appears to be the oldest undisputed example of Upper Paleolithic art and figurative sculpture of the human form in general, from over 35,000 years BP, which was only discovered in 2008;[1] the better-known Venus of Willendorf (24–22,000 BP) comes from a little way over the Austrian border. The spectacular finds of Bronze Age golden hats are centred on Germany, as was the "central" form of Urnfield culture, and Hallstatt culture.

In the

]After lengthy wars, the Roman Empire settled its frontiers in Germania with the Limes Germanicus to include much of the south and west of modern Germany. The German provinces produced art in provincial versions of Roman styles, but centres there, as over the Rhine in France, were large-scale producers of fine Ancient Roman pottery, exported all over the Empire. [citation needed] Rheinzabern was one of the largest, which has been well-excavated and has a dedicated museum.[2]

Non-Romanized areas of the later Roman period fall under Migration Period art, notable for metalwork, especially jewellery (the largest pieces apparently mainly worn by men). [citation needed]

Middle Ages

Carolingian art

German medieval art really begins with the

No Carolingian

Ottonian art

Under the next Ottonian dynasty, whose core territory approximated more closely to modern Germany, Austria, and German-speaking Switzerland, Ottonian art was mainly a product of the large monasteries, especially Reichenau which was the leading Western artistic centre in the second half of the 10th century. The Reichenau style uses simplified and patterned shapes to create strongly expressive images, far from the classical aspirations of Carolingian art, and looking forward to the Romanesque. The wooden Gero Cross of 965–970 in Cologne Cathedral is both the oldest and the finest early medieval near life-size crucifix figure; art historians had been reluctant to credit the records giving its date until they were confirmed by dendrochronology in 1976.[5] As in the rest of Europe, metalwork was still the most prestigious form of art, in works like the jewelled Cross of Lothair, made about 1000, probably in Cologne.[citation needed]

Romanesque art

Romanesque art was the first artistic movement to encompass the whole of Western Europe, though with regional varieties. Germany was a central part of the movement, though German Romanesque architecture made rather less use of sculpture than that of France. With increasing prosperity massive churches were built in cities all over Germany, no longer just those patronized by the Imperial circle.[6]

Gothic art

The French invented the

The court of the

Like that of Pacher, the workshop of

Martin Schongauer, who worked in Alsace in the last part of the 15th century, was the culmination of late Gothic German painting, with a sophisticated and harmonious style, but he increasingly spent his time producing engravings, for which national and international channels of distribution had developed, so that his prints were known in Italy and other countries. His predecessors were the Master of the Playing Cards and Master E. S., both also from the Upper Rhine region.[11] German conservatism is shown in the late use of gold backgrounds, still used by many artists well into the 15th century.[12]

Renaissance painting and prints

The concept of the Northern Renaissance or German Renaissance is somewhat confused by the continuation of the use of elaborate Gothic ornament until well into the 16th century, even in works that are undoubtedly Renaissance in their treatment of the human figure and other respects. Classical ornament had little historical resonance in much of Germany, but in other respects Germany was very quick to follow developments, especially in adopting printing with movable type, a German invention that remained almost a German monopoly for some decades, and was first brought to most of Europe, including France and Italy, by Germans.[citation needed]

Printmaking by woodcut and engraving (perhaps another German invention) was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than anywhere else, and the Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations, typically of a relatively low artistic standard, but seen all over Europe, with the woodblocks often being lent to printers of editions in other cities or languages. The greatest artist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer, began his career as an apprentice to a leading workshop in Nuremberg, that of Michael Wolgemut, who had largely abandoned his painting to exploit the new medium. Dürer worked on the most extravagantly illustrated book of the period, the Nuremberg Chronicle, published by his godfather Anton Koberger, Europe's largest printer-publisher at the time.[13]

After completing his apprenticeship in 1490, Dürer travelled in Germany for four years, and Italy for a few months, before establishing his own workshop in Nuremberg. He rapidly became famous all over Europe for his energetic and balanced woodcuts and engravings, while also painting. Though retaining a distinctively German style, his work shows strong Italian influence, and is often taken to represent the start of the German Renaissance in visual art, which for the next forty years replaced the Netherlands and France as the area producing the greatest innovation in Northern European art. Dürer supported

Dürer died in 1528, before it was clear that the split of the Reformation had become permanent, but his pupils of the following generation were unable to avoid taking sides. Most leading German artists became Protestants, but this deprived them of painting most religious works, previously the mainstay of artists' revenue.

Lying somewhat outside these developments is Matthias Grünewald, who left very few works, but whose masterpiece, his Isenheim Altarpiece (completed 1515), has been widely regarded as the greatest German Renaissance painting since it was restored to critical attention in the 19th century. It is an intensely emotional work that continues the German Gothic tradition of unrestrained gesture and expression, using Renaissance compositional principles, but all in that most Gothic of forms, the multi-winged triptych.[15]

The

The outstanding achievements of the first half of the 16th century were followed by several decades with a remarkable absence of noteworthy German art, other than accomplished portraits that never rival the achievement of Holbein or Dürer. The next significant German artists worked in the rather artificial style of

Gothic and Renaissance sculpture

In Catholic parts of South Germany the Gothic tradition of wood carving continued to flourish until the end of the 18th century, adapting to changes in style through the centuries. Veit Stoss (d. 1533), Tilman Riemenschneider (d.1531) and Peter Vischer the Elder (d. 1529) were Dürer's contemporaries, and their long careers covered the transition between the Gothic and Renaissance periods, although their ornament often remained Gothic even after their compositions began to reflect Renaissance principles.[21]

Two and a half centuries later,

17th to 19th-century painting

Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassicism

The earliest German

Writing about art

The Enlightenment period saw German writers becoming leading theorists and critics of art, led by

The emergence of art as a major subject of philosophical speculation was solidified by the appearance of

Romanticism and the Nazarenes

The

Led by the Nazarene Schadow, son of the sculptor, the

Naturalism and beyond

In the second half of the 19th century a number of styles developed, paralleling trends in other European counties, though the lack of a dominant capital city probably contributed to even more diversity of styles than in other countries.[37]

The

20th century

Even more than in other countries, German art in the early 20th century developed through a number of loose groups and movements, many covering other artistic media as well, and often with a specific political element, as with the Arbeitsrat für Kunst and November Group, both formed in 1918. In 1922 The November Group, the Dresden Secession, Das Junge Rheinland, and several other progressive groups formed a "Cartel of advanced artistic groups in Germany" (Kartell fortschrittlicher Künstlergruppen in Deutschland) in an effort to gain exposure.[41]

Der Blaue Reiter ("The Blue Rider") formed in Munich, Germany in 1911. Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin and others founded the group in response to the rejection of Kandinsky's painting Last Judgment from an exhibition by Neue Künstlervereinigung—another artists' group of which Kandinsky had been a member. The name Der Blaue Reiter derived from Marc's enthusiasm for horses, and from Kandinsky's love of the colour blue. For Kandinsky, blue is the colour of spirituality—the darker the blue, the more it awakens human desire for the eternal (see his 1911 book On the Spiritual in Art). Kandinsky had also titled a painting Der Blaue Reiter (see illustration) in 1903.[43] The intense sculpture and printmaking of Käthe Kollwitz was strongly influenced by Expressionism, which also formed the starting point for the young artists who went on to join other tendencies within the movements of the early 20th century.[44]

Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter were both examples of tendency of early 20th-century German art to be "honest, direct, and spiritually engaged"[45] The difference in how the two groups attempted this were telling, however. The artists of Der Blaue Reiter were less oriented towards intense expression of emotion and more towards theory- a tendency which would lead Kandinsky to pure abstraction. Still, it was the spiritual and symbolic properties of abstract form that were important. There were therefore Utopian tones to Kandinsky's abstractions: "We have before us an age of conscious creation, and this new spirit in painting is going hand in hand with thoughts toward an epoch of greater spirituality."[46] Die Brücke also had Utopian tendencies, but took the medieval craft guild as a model of cooperative work that could better society- "Everyone who with directness and authenticity conveys that which drives him to creation belongs to us".[47] The Bauhaus also shared these Utopian leanings, seeking to combine fine and applied arts (Gesamtkunstwerk) with a view towards creating a better society. [citation needed]

Weimar period

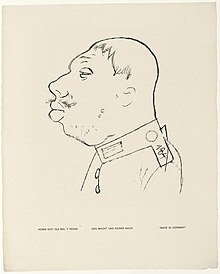

A major feature of German art in the early 20th century until 1933 was a boom in the production of works of art of a

The

Plakatstil, "poster style" in German, was an early style of poster design that began in the early 20th century, using bold, straight fonts with very simple designs, in contrast to Art Nouveau posters. Lucian Bernhard was a leading figure. [citation needed]

Art in the Third Reich

The Nazi regime banned

In July, 1937, the Nazis mounted a polemical exhibition entitled Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art), in Munich; it subsequently travelled to eleven other cities in Germany and Austria. The show was intended as an official condemnation of modern art, and included over 650 paintings, sculptures, prints, and books from the collections of thirty two German museums. Expressionism, which had its origins in Germany, had the largest proportion of paintings represented. Simultaneously, and with much pageantry, the Nazis presented the Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art). This exhibition displayed the work of officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. At the end of four months Entartete Kunst had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the nearby Grosse deutsche Kunstausstellung.[54]

Post-World War II art

Post-war art trends in Germany can broadly be divided into Socialist realism in the DDR (communist East Germany), and in West Germany a variety of largely international movements including Neo-expressionism and Conceptualism.[citation needed]

Notable socialist realism include or included Walter Womacka, Willi Sitte, Werner Tübke and Bernhard Heisig.

Especially notable neo-expressionists include or included Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, A. R. Penck, Markus Lüpertz, Peter Robert Keil and Rainer Fetting. Other notable artists who work with traditional media or figurative imagery include Martin Kippenberger, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Neo Rauch.[citation needed]

Leading German conceptual artists include or included Bernd and Hilla Becher, Hanne Darboven, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Hans Haacke, and Charlotte Posenenske.[55]

The

Famous for their happenings are HA Schult and Wolf Vostell. Wolf Vostell is also known for his early installations with television. His first installations with television the Cycle Black Room from 1958 was shown in Wuppertal at the Galerie Parnass in 1963 and his installation 6 TV Dé-coll/age was shown at the Smolin Gallery [57] in New York also in 1963.[58][59]

The art group Gruppe SPUR included: Lothar Fischer (1933–2004), Heimrad Prem (1934–1978), Hans-Peter Zimmer (1936–1992) and Helmut Sturm (1932). The SPUR-artists met first at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich and, before falling out with them, were associated with the Situationist International. Other groups include the Junge Wilde of the late 1970s to early 1980s.[citation needed]

documenta (sic) is a major exhibition of contemporary art held in Kassel every five years (2007, 2012...), Art Cologne is an annual art fair, again mostly for contemporary art, and Transmediale is an annual festival for art and digital culture, held in Berlin.[citation needed]

Other contemporary German artists include Jonathan Meese, Daniel Richter, Albert Oehlen, Markus Oehlen, Rosemarie Trockel, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Blinky Palermo, Hans-Jürgen Schlieker, Günther Uecker, Aris Kalaizis, Katharina Fritsch, Fritz Schwegler and Thomas Schütte.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ Venus figurine sheds light on origins of art by early humans Los Angeles Times, May 14, 2009, accessed December 11, 2009

- ^ Terra Sigillata Museum Rheinzabern (in German)

- ^ See Hinks throughout, Chapters 1 of Beckwith and 3–4 of Dodwell

- ^ Dodwell, 32 on the Libri Carolini

- ^ Beckwith, Chapter 2

- ^ Beckwith, Chapter 3

- ^ Focillon, 106

- ^ Dodwell, Chapter 7

- ^ Levey, 24-7, 37 & passim, Snyder, Chapter II

- ^ Snyder, 308

- ^ Snyder, Chapters IV (painters to 1425), VII (painters to 1500), XIV (printmakers), & XV (sculpture).

- ^ Focillon, 178–181

- ^ a b Bartrum (2002)

- ^ Snyder, Part III, Ch. XIX on Cranach, Luther etc.

- ^ Snyder, Ch. XVII

- ^ Wood, 9 – this is the main subject of the whole book

- ^ Snyder, Ch. XVII, Bartrum, 1995

- ^ "BBC - Dark arts: Holbein and the court of Henry VIII". BBC. Retrieved 2021-12-30.

- ^ Snyder, Ch. XX on the Holbeins, Bartrum (1995), 221–237 on Holbein's prints, 99–129 on the Little Masters

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Levey

- ^ Snyder, 298–311

- ^ Savage, 156

- ^ Griffiths & Carey, 24 (quotation), and Scheyer, 9 (from 1960, but the point remains valid)

- ^ Novotny, 62–65

- ^ Novotny, 49–59

- ^ Griffiths & Carey, 50–68, Novotny, 60–62

- ^ Novotny, 60

- ^ Gombrich, 352–357; quotes from pp. 355 & 357

- ^ Novotny, 78 (quotation); and see index for Winckelmann etc.

- Butler, Eliza M., "The Tyranny of Greece over Germany: a study of the influence exercised by Greek art and poetry over the great German writers of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries" (Cambridge Univ. Press, London, 1935)

- ^ Novotny, 95–101

- ^ Novotny, 106–112

- ^ Griffiths and Carey, 112–122

- ^ Griffiths & Carey, 24–25 and passim, quotation from p. 24

- ^ John K. Howat: American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, S. 311

- ^ Doyle, Margaret, in Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850, Volume 1,

ed. Christopher John Murray, p. 89, Taylor & Francis, 2004 ISBN 1-57958-361-X, Google books

- ^ Hamilton, 180

- ^ Wilhelm Leibl. The art of seeing, Kunsthaus Zürich, 2019

- ^ Hamilton, 181–184, and see index for later mentions

- ^ Hamilton, 113

- ISBN 0271043164.

- ^ Hamilton, 197–204, and Honour & Fleming, 569–576

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 569–576, and Hamilton, 215–221

- ^ Hamilton, 189–191

- ^ Hunter, Jacobus, and Wheeler (2000) p. 113

- ^ qtd. Hunter et al p. 118

- ^ From the Manifesto of Die Brücke, qtd Hunter et al p. 113

- ISBN 978-0-7546-0226-2

- ISBN 978-3-7913-3195-9

- ^ a b Hunter, Jacobus, and Wheeler (2000) pp. 173–77

- ^ Hamilton, 473–478

- ^ Hamilton, 478–479

- ^ "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ^ Hamilton, 486–487

- ^ Marzona, Daniel. (2005) Conceptual Art. Cologne: Taschen. Various pages

- ^ Moma Focus, retrieved 16 December 2009

- ISBN 3-925520-44-9

- ^ Wolf Vostell, Cycle Black Room, 1958, installation with television

- ^ Wolf Vostell, 6 TV Dé-coll/age, 1963, installation with television

References

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Germany |

|---|

|

| Festivals |

| Music |

Further reading

- German masters of the nineteenth century: paintings and drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1981. ISBN 978-0-87099-263-6.

- Nancy Marmer, "Isms on the Rhine: Westkunst," Art in America, Vol. 69, November 1981, pp. 112–123.