Pretoria

Pretoria

Tshwane | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Municipality City of Tshwane | | |

| Established | 18 November 1855 | |

| Founded by | Marthinus Wessel Pretorius | |

| Named for | Andries Pretorius | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Metropolitan municipality | |

| • Mayor | Cilliers Brink (DA) | |

| Area | ||

| • Capital city (executive branch) | 687.54 km2 (265.46 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 6,297.83 km2 (2,431.61 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 1,339 m (4,393 ft) | |

| Population (2023)[1] | ||

| • Capital city (executive branch) | 2,818,100 | |

| • Rank | 33rd in Africa US$ 75.6 billion[4] | |

| GDP per capita | US$ 23,108[4] | |

| Website | tshwane.gov.za | |

| Zulu | iPitoli |

|---|---|

| Xhosa | ePitoli |

| Afrikaans | Pretoria |

| Sepedi | Pretoria |

| Swazi | Pitoli |

| Sesotho | Pritoriya |

| Setswana | Tshwane |

| Xitsonga | Pitori |

| Venda | Pretoria |

Pretoria (

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foothills of the Magaliesberg mountains. It has a reputation as an academic city and center of research, being home to the Tshwane University of Technology (TUT), the University of Pretoria (UP), the University of South Africa (UNISA), the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), and the Human Sciences Research Council. It also hosts the National Research Foundation and the South African Bureau of Standards. Pretoria was one of the host cities of the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

Pretoria is the central part of the

Pretoria is named after the

History

Pretoria was founded in 1855 by

The founding of Pretoria as the capital of the South African Republic can be seen as marking the end of the Boers' settlement movements of the Great Trek.

Boer Wars

During the First Boer War, the city was besieged by Republican forces in December 1880 and March 1881. The peace treaty that ended the war was signed in Pretoria on 3 August 1881 at the Pretoria Convention.

The

The Pretoria Forts were built for the defence of the city just prior to the Second Boer War. Though some of these forts are today in ruins, a number of them have been preserved as national monuments.

Union of South Africa

The Boer Republics of the ZAR and the

Geography

Pretoria is situated approximately 56 km (35 mi) north-northeast of

Climate

Pretoria has a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cwa) with long hot, rainy summers, and short, dry and mild winters. The city experiences the typical winters of South Africa, with cold, clear nights and mild to moderately warm days. Although the average lows during winter are mild, it can get cold due to the clear skies, with night time low temperatures in recent years in the range of 2 to −5 °C (36 to 23 °F).

The average annual temperature is 18.7 °C (65.7 °F).[14] This is rather high, considering the city's relatively high altitude of about 1,339 metres (4,393 feet), and is due mainly to its sheltered valley position, which acts as a heat trap and cuts it off from cool southerly and south-easterly air masses for much of the year.[citation needed]

Rain is chiefly concentrated in the summer months, with drought conditions prevailing over the winter months, when frosts may be sharp. Snowfall is an extremely rare event; snowflakes were spotted in 1959, 1968 and 2012 in the city, but the city has never experienced an accumulation in its history.

During a nationwide heat wave in November 2011, Pretoria experienced temperatures that reached 39 °C (102 °F), unusual for that time of the year. Similar record-breaking extreme heat events also occurred in January 2013, when Pretoria experienced temperatures exceeding 37 °C (99 °F) on several days. The year 2014 was one of the wettest on record for the city. A total of 914 mm (36 in) fell up to the end of December, with 220 mm (9 in) recorded in this month alone. In 2015, Pretoria saw its worst drought since 1982; the month of November 2015 saw new records broken for high temperatures, with 43 °C (109 °F) recorded on 11 November after three weeks of temperatures between 35 °C (95 °F) and 43 °C (109 °F). Pretoria reached a new record high of 42.7 °C (108.9 °F) on 7 January 2016.[15]

| Climate data for Pretoria (1961–1990 with extremes 1951–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.2 (97.2) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.3 (97.3) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 33.2 (91.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.5 (83.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.7 (33.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 135 (5.3) |

76 (3.0) |

79 (3.1) |

54 (2.1) |

13 (0.5) |

7 (0.3) |

3 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

20 (0.8) |

73 (2.9) |

100 (3.9) |

108 (4.3) |

673 (26.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.9 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 64.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%)

|

62 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 56 | 54 | 50 | 45 | 44 | 52 | 59 | 61 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 260.8 | 235.3 | 253.9 | 245.8 | 282.6 | 270.8 | 289.1 | 295.5 | 284.3 | 275.2 | 253.6 | 271.9 | 3,218.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA,[16] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes)[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: South African Weather Service[18] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Depending on the extent of the area understood to constitute "Pretoria", the population ranges from 700,000

Ethnic groups

Even since the end of Apartheid, Pretoria itself has had a white majority, albeit with an ever-increasing black middle-class. However, in the townships of

The lower estimate for the population of Pretoria includes largely former white-designated areas, and there is therefore a white majority. However, including the geographically separate townships increases Pretoria's population beyond a million and makes whites a minority.

Pretoria's Indians were ordered to move from Pretoria to Laudium on 6 June 1958.[21]

| Ethnic group | 2001 population | 2001 (%) | 2011 population | 2011 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

White |

355,631 | 67.7% | 389,022 | 52.5% |

Black African |

128,791 | 24.5% | 311,149 | 42.0% |

Coloured |

32,727 | 6.2% | 18,514 | 2.5% |

Indian or Asian |

8,238 | 1.6% | 14,298 | 1.9% |

| Other | – | – | 8,667 | 1.2% |

| Total | 525,387 | 100% | 741,651 | 100% |

Cityscape

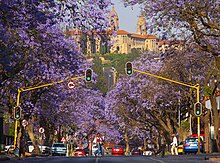

Pretoria is known as the "Jacaranda City" due to the approximately 50,000 Jacarandas that line its streets. Purple is a colour often associated with the city and is often included on local council logos and services such as the A Re Yeng rapid bus system and the logo of the local Jacaranda FM radio station.

Architecture

Media related to Buildings in Pretoria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Buildings in Pretoria at Wikimedia Commons

Pretoria has over the years had very diverse cultural influences and this is reflected in the architectural styles that can be found in the city. It ranges from 19th century Dutch, German and British colonial architecture to modern, postmodern, neomodern, and art deco architecture styles with a good mix of a uniquely South African style.

Some of the notable structures in Pretoria include the late 19th century

-

The Eastern Wing of the Union Buildings

-

Old Council Chambers, or Ou Raadsaal

-

Neomodern architecture in Pretoria

-

The Palace of Justice

-

The Old Synagogue

Central business district

Despite the many corporate offices, small businesses, shops, and government departments that are situated in

The area contains a large number of historical buildings, monuments, and museums that include the

Several National Departments also have Head Offices in the Central Business district such as the Department of Health, Basic Education, Transport, Higher Education and Training, Sport and Recreation, Justice and Constitutional Development, Public Service and Administration, Water and Environmental Affairs and the National Treasury. The district also has a high number of residential buildings which house people who primarily work in the district.

Parks and gardens

Pretoria is home to the

, the oldest park in the city and now a national monument. In the suburbs there are also several parks that are notable: Rietondale Park, "Die Proefplaas" in the Queenswood suburb, Magnolia Dell Park, Nelson Mandela Park and Mandela Park Peace Garden and Belgrave Square Park.Jacaranda city

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2019) |

Pretoria's nickname "the Jacaranda City" comes from the around 70,000 jacaranda trees that grow in Pretoria and decorate the city each October with their purple blossoms. The first two trees were planted in 1888 in the garden of local gardener, J.D. Cilliers, at Myrtle Lodge on Celliers Street in Sunnyside. He obtained the seedlings from a Cape Town nurseryman who had harvested them in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The two trees still stand on the grounds of the Sunnyside Primary School.

The jacaranda comes from tropical South America and belongs to the family Bignoniaceae. There are around fifty species of jacaranda, but the one found most often in the warmer areas of Southern Africa is Jacaranda mimosifolia.

At the end of the 19th century, the flower and tree grower James Clark imported jacaranda seedlings from Australia and began growing them on a large scale. In November 1906, he donated two hundred small saplings to the Pretoria City Council, which planted them on Koch Street (today Bosman Street). The city engineer Walton Jameson, soon known as "Jacaranda Jim", launched a program to plant jacaranda trees throughout Pretoria, and by 1971 there would already be 55,000 of them in the city.

Most jacarandas in Pretoria are lilac in colour, but there are also white ones planted on Herbert Baker Street in Groenkloof.

The Jacaranda Carnival is an old tradition that was held from 1939 to 1964. After a hiatus of over twenty years, it resumed in 1985. Festivities include a colourful march and the crowning of the Jacaranda Queen.[24]

Suburbs

Transportation

Railway

Commuter rail services around Pretoria are operated by Metrorail. The routes, originating from the city centre, extend south to Germiston and Johannesburg, west to Atteridgeville, northwest to Ga-Rankuwa, north to Soshanguve and east to Mamelodi. Via the Pretoria–Maputo railway it is possible to access the port of Maputo, in the east.[25]

The

Pretoria Station is a departure point for the Blue Train luxury train. Rovos Rail,[26] a luxury mainline train safari service operates from the colonial-style railway station at Capital Park.[27] The South African Friends of the Rail have recently moved their vintage train trip operations from the Capital Park station to the Hercules station.[28]

Buses

Various bus companies exist in Pretoria, of which PUTCO is one of the oldest and most recognised. Tshwane municipality provides the remainder of the bus services.[29]

Road

The

The

There is a third, original east–west road: the

The

The

The

Pretoria is also served by many regional roads. The

Pretoria is also served internally by metropolitan routes.

Airports

For scheduled air services, Pretoria is served by Johannesburg's airports:

Culture

Media

Since Pretoria forms part the

Radio

There are many radio stations in the greater Pretoria region, some of note are:

Tuks FM is the radio station of the University of Pretoria and one of South Africa's community broadcasters. It was one of the first community broadcasters in South Africa to be given an FM licence. It is known for contemporary music and is operated by UP's student base.

Impact Radio, is a Christian Community Radio Station based in Pretoria, and broadcasting on 103FM in the Greater Tshwane Area.

Television

Pretoria is serviced by

Paper

The city is serviced by a variety of printed publications namely;

Pretoria News is a daily newspaper established in Pretoria in 1898. It publishes a daily edition from Monday to Friday and a Weekend edition on Saturday and Sunday. It is an independent newspaper in the English language that serves the city and its direct environs. It is available online via the Independent online website.

Beeld is an Afrikaans-language daily newspaper that was launched on 16 September 1974. Beeld is distributed in four provinces of South Africa: Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Limpopo, North West. Die Beeld (English: The Image) was an Afrikaans-language Sunday newspaper in the late 1960s.

Pretoria Creole

Pretoria Sotho (called Sepitori by its speakers)

Museums

- Ditsong National Museum of Cultural History, a.k.a. African Window

- Freedom Park

- Hapo Museum

- Kruger House (residence of the president of the ZAR, Paul Kruger)

- Mapungubwe Museum

- Anglo-Boer Warwas signed here in 1902)

- National Library of South Africa[31]

- Pioneer Museum

- Pretoria Art Museum

- Pretoria Forts

- South African Air Force Museum

- Transvaal Museum

- Van Tilburg Collection

- Van Wouw Museum

- Voortrekker Monument

- Willem Prinsloo Agricultural Museum

- Sammy Marks House[32]

- SP Engelbrecht Museum (history of the NHK church)

- Smuts House Museum

-

Freedom Park's amphitheatre

-

African Window

-

Paul Kruger's House

-

Melrose House

Music

A number of popular South African bands and musicians are originally from Pretoria. These include Desmond and the Tutus, Bittereinder, The Black Cat Bones, Seether, popular mostwako rapper JR, Joshua na die Reën and DJ Mujava who was raised in the town of Attridgeville.

The song "Marching to Pretoria" refers to this city. Pretoria was the capital of the South African Republic (a.k.a. Republic of the Transvaal; 1852–1881 and 1884–1902) the principal battleground for the First and Second Boer War, the latter which brought both the Transvaal and the Orange Free State republic under British rule. "Marching to Pretoria" was one of the songs that British soldiers sang as they marched from the Cape Colony, under British Rule since 1814, to the capital of the Southern African Republic (or in Dutch, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek). As the song's refrain puts it: "We are marching to Pretoria, Pretoria, Pretoria/We are marching to Pretoria, Pretoria, Hurrah."[33]

The opening line of

Performing arts and galleries

Pretoria is home to an extensive portfolio of public art. A diverse and evolving city, Pretoria boasts a vibrant art scene and a variety of works that range from sculptures to murals to pieces by internationally and locally renowned artists. The Pretoria Art Museum is home to a vast collection of local artworks. After a bequest of 17th century Dutch artworks by Lady Michaelis in 1932 the art collection of Pretoria City Council expanded quickly to include South African works by Henk Pierneef, Pieter Wenning, Frans Oerder, Anton van Wouw and Irma Stern.[36] And according to the museum: "As South African museums in Cape Town and Johannesburg already had good collections of 17th, 18th and 19th century European art, it was decided to focus on compiling a representative collection of South African art" making it somewhat unusual compared to its contemporaries.[36]

Pretoria houses several performing arts venues including:[37] the

and comedic performances.A 9 metre tall statue of former president Nelson Mandela was unveiled in front of the Union Buildings on 16 December 2013.[38] Since Nelson Mandela's inauguration as South Africa's first majority elected president the Union Buildings have come to represent the new 'Rainbow Nation'.[39] Public art in Pretoria has flourished since the 2010 FIFA World Cup with many areas receiving new public artworks.[40]

Sport

One of the most popular sports in Pretoria is

Pretoria also hosted matches during the 1995 Rugby World Cup. Loftus Versfeld was used for some matches in the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

The Pretoria Transnet Blind Cricket Club is situated in Pretoria and is the biggest Blind Cricket club in South Africa. Their field is at the Transnet Engineering campus on Lynette Street, home of differently disabled cricket. PTBCC has played many successful blind cricket matches with abled bodied teams such as the South African Indoor Cricket Team and TuksCricket Junior Academy. Northerns Blind Cricket is the Provincial body that governs PTBCC and Filefelfia Secondary School. The Northern Blind Cricket team won the 40 over National Blind Cricket tournament that was held in Cape Town in April 2014.[44]

The city's SunBet Arena at Time Square hosted the NBA Africa Game 2018.[45]

Places of worship

Among the

Jewish community

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

Pretoria has a small Jewish community of around 3,000.

Other early Jewish settlers, many of them immigrants from

The first congregation was founded between 1890 and 1895, and in 1898 the first synagogue,

The Jewish community of Pretoria's golden age was in the early 20th century, when many Jewish sports clubs, charities, and youth groups flourished. After 1948, many Jews left for Cape Town or Johannesburg.

The Old Synagogue on Paul Kruger Street was purchased by the government in 1952 to become the new home of the High Court where prominent opposition figures in the Anti-Apartheid Movement were tried, including Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, and 26 others were prosecuted for treason from 1 August 1958 to 29 March 1961; the Rivonia Trial was held there in 1963–1964.[48]

Two Jewish schools arose in Pretoria, the Miriam Marks School, which was founded in 1905, and the Carmel School, which opened in 1959. Only the second, currently also operating as a synagogue, remains. Pretoria's Reformed congregation shares a rabbi with the Johannesburg one, though the synagogue no longer operates and services take place in worshippers' private homes.

Buddhist community

A Buddhist center, the Jang Chup Chopel Rigme Centre ("Center of Light") was founded in early January 2015 by Duan Pienaar or Gyalten Nyima (his adopted monastic name) in Waverley around Pretoria-Moot. Pienaar is the only Afrikaner ordained in the highly selective Tibetan Tantric Buddhist community in Bylakuppe, in southern India. His instructor Lama Kyabje Choden Rinpoche is the highest tantric master after the Dalai Lama. Pienaar, who studied Buddhist teachers for twenty years, spent two years in India.[49][50]

Coat of arms

The Pretoria civic arms, designed by Frans Engelenburg,[51] were granted by the College of Arms on 7 February 1907. They were registered with the Transvaal Provincial Administration in March 1953[52] and at the Bureau of Heraldry in May 1968.[53] The Bureau provided new artwork, in a more modern style, in 1989.[54]

The arms were: Gules, on an mimosa tree eradicated proper within an orle of eight bees volant, Or, an inescutcheon Or and thereon a Roman praetor seated proper. In layman's terms: a red shield displaying an uprooted mimosa tree surrounded by a border of eight golden bees, superimposed on the tree is a golden shield depicting a Roman praetor. The tree represented growth, the bees industry, and the praetor (judge) was an heraldic pun on the name.

The crest was a three-towered golden castle; the supporters were an eland and a kudu; and the motto Praestantia praevaleat Pretoria. The coat of arms have gone out of favour after the City Council amalgamated with its surrounding councils to form the City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality.

Education

Primary education

Secondary education

- Afrikaanse Hoër Meisieskool

- Afrikaanse Hoër Seunskool

- Christian Brothers' College

- Clapham High School

- Cornwall Hill College

- Crawford College

- The Glen High School

- Hillview High School

- Hoërskool Die Wilgers

- Hoërskool Garsfontein

- Hoërskool Menlopark

- Hoërskool Montana

- Hoërskool Oos-Moot

- Hoërskool Overkruin

- Hoërskool Waterkloof

- Hoërskool Wonderboom

- Pretoria Boys High School

- Pretoria Chinese School

- Pretoria High School for Girls

- Pretoria North High School

- Pretoria Secondary School

- Pro Arte Alphen Park

- St. Alban's College

- St. Mary's Diocesan School for Girls

- Tshwane Muslim School

- Willowridge High School

International schools

- École Miriam Makeba (French school)

- Deutsche Schule Pretoria(German school)

- AISJ-Pretoria

Tertiary education

Pretoria is one of South Africa's leading academic cities and is home to both the largest residential university in South Africa, largest distance education university in South Africa and a research intensive university.[55] The three Universities in the city in order of the year founded are as follows:

University of South Africa

The University of South Africa (commonly referred to as Unisa), founded in 1873 as the University of the Cape of Good Hope, is the largest university on the African continent and attracts a third of all higher education students in South Africa. It spent most of its early history as an examining agency for Oxford and Cambridge universities and as an incubator from which most other universities in South Africa are descended. In 1946 it was given a new role as a distance education university and in 2012 it had a student headcount of over 300,000 students, including African and international students in 130 countries worldwide, making it one of the world's mega universities. Unisa is a dedicated open distance education institution and offers both vocational and academic programmes.

University of Pretoria

The

Tshwane University of Technology

The

CSIR

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) is South Africa's central scientific research and development organisation. It was established by an act of parliament in 1945 and is situated on its own campus in the city.[61] It is the largest research and development organisation in Africa and accounts for about 10% of the entire African R&D budget. It has a staff of approximately 3,000 technical and scientific researchers, often working in multi-disciplinary teams. In 2002, Sibusiso Sibisi was appointed as the president and CEO of the CSIR.

Military

Pretoria has earned a reputation as being the centre of South Africa's Military and is home to several military facilities of the South African National Defence Force:

Military headquarters

Transito Air Force Headquarters

This complex is the headquarters to the South African Air Force.

The Dequar Road Complex

A military complex that houses the following:

- South African Army's Headquarters

- South African Infantry FormationHQ

- A General Support Base

- Support Formation HQ

- Training Formation HQ

- The 102 Field Workshop unit

- The 17 Maintenance Unit

- The S.A.M.S Military Health Department[62]

The Sebokeng Complex

A military complex located on the corner of Patriot Street and Koraalboom Road[63] that houses the following military headquarters:

- South African Army Armour FormationHQ

- South African Army Artillery Formation HQ

- South African Army Intelligence Corps HQ

- South African Army Air Defence Artillery Formation HQ[62]

Military bases

The Dequar Road Base

This base is situated in the suburb of Salvokop and is divided into two parts:

- The Green Magazine (Groen Magazyn) which is the Headquarters to the Transvaalse Staatsartillerie, a reserve artillery regiment of the South African Army[64]

- Magazine Hill which is the regimental Headquarters to the

Thaba Tshwane

Thaba Tshwane is a large military area south-west of the Pretoria Central Business District and North of Air Force Base Swartkop. It is the headquarters of several army units-

- Joint Support Base Garrison that is responsible for the town management of Thaba Tshwane

- The Tshwane Regiment, a reserve motorised infantry regiment of the South African Army[66]

- The 18 Light Regiment, a reserve artillery regiment of the South African Army[64]

- The National Ceremonial Guard and Band

The military base also houses the 1 Military Hospital and the Military Police School. Within Thaba Tshwane, a facility known as "TEK Base" exists which houses its own units:

- The SA Army Engineer Formation

- 2 Parachute Battalion

- 44 Parachute Engineer Regiment

- 1 Military Printing Regiment

- 4 Survey and Map Regiment[62]

Joint Support Base Wonderboom

The Wonderboom Military Base is located adjacent to the Wonderboom Airport and is the headquarters of the South African Army Signals Formation. It also houses the School of Signals, 1 Signal Regiment, 2 Signal Regiment, 3 Electronic Workshop, 4 Signal Regiment and 5 Signal Regiment.[67]

Military colleges

The South African Air Force College, the South African Military Health Service School for Military Health Training and the South African Army College are situated in the Thaba Tshwane Military Base and are used to train Commissioned and Non-commissioned Officers to perform effectively in combat/command roles in the various branches of the South African National Defence Force. The South African Defence Intelligence College is also located in the Sterrewag Suburb north of Air Force Base Waterkloof.[62][68]

Air force bases

While technically not within the city limits of Pretoria, Air Force Base Swartkop and Air Force Base Waterkloof are often used for defence related matters within the city. These may include aerial military transport duties within the city, aerospace monitoring and defence as well as VIP transport to and from the city.

Proposed change of name

On 26 May 2005 the

The Tshwane Metro Council has advertised "Africa's leading capital city" as Tshwane since the SAGNC decision in 2005. This has led to further controversy, however, as the name of the city had not yet been changed, and the council was, at best, acting prematurely. When a complaint was lodged with the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), it ruled that such advertisements are deliberately misleading and should be withdrawn from all media.[70] Despite the rulings of the ASA, Tshwane Metro Council failed to discontinue their "City of Tshwane" advertisements. As a result, the ASA requested that Tshwane Metro pay for advertisements in which it admits that it has misled the public. After refusing to abide by the ASA's request, the Metro Council was banned from placing any advertisements in the South African media that refer to the capital as Tshwane. ASA may still place additional sanctions on the Metro Council that would prevent it from placing any advertisements in the South African media, including council notices and employment vacancies.[71][72]

After the ruling, the Metro Council continued to place Tshwane advertisements, but placed them on council-owned advertising boards and busstops throughout the municipal area. In August 2007, an internal memo was leaked to the media in which the Tshwane mayor sought advice from the premier of Gauteng on whether the municipality could be called the "City of Tshwane" instead of just "Tshwane".[73] This could increase confusion about the distinction between the city of Pretoria and the municipality of Tshwane.

In early 2010 it was again rumoured that the South African government would make a decision regarding the name; however, a media briefing regarding name changes, which could have been an opportunity to discuss it, was cancelled shortly before taking place.

In March 2010 a group supporting the name change, calling themselves the "Tshwane Royal House Committee", claimed to be descendants of Chief Tshwane and demanded to be made part of the administration of the municipality.[82]

According to comments made by Mayor

As of 2023[update], the proposed name change has not occurred.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Pretoria is twinned with:

Amman, Jordan[citation needed]

Amman, Jordan[citation needed] Baku, Azerbaijan[86]

Baku, Azerbaijan[86] Bucharest, Romania[87]

Bucharest, Romania[87] Bulawayo, Zimbabwe[88]

Bulawayo, Zimbabwe[88] Kumasi, Ghana[citation needed]

Kumasi, Ghana[citation needed] Kyiv, Ukraine[89]

Kyiv, Ukraine[89] Port Louis, Mauritius[90]

Port Louis, Mauritius[90] Taipei, Taiwan[91]

Taipei, Taiwan[91] Tehran, Iran[92]

Tehran, Iran[92] Washington, D.C., United States[93]

Washington, D.C., United States[93]

Notable people

- Anel Alexander, actress

- Frances Ames, neurologist, psychiatrist and human rights activist

- Melinda Bam, Miss South Africa 2011

- Johan Barkhuizen, cricketer

- Margaret Becklake, academic and epidemiologist

- Daniel Bekker, athlete

- Deanne Bergsma, dancer

- Conrad Bo, artist

- Roelof Botha, venture capitalist

- Wim Botha, artist

- Rory Byrne, Chief designer at the Benetton and Scuderia Ferrari Formula One teams

- Jan-Henning Campher – Rugby union player

- Sharlto Copley, actor

- Kurt Darren, singer/songwriter

- Rassie van der Dussen, cricketer

- Damon Galgut, Booker Prize-winning author

- Branden Grace, golfer

- Nigel Green, actor

- George Gristock, Victoria Cross recipient

- Steve Hofmeyr, singer, songwriter and actor

- Bobby van Jaarsveld, South African singer/songwriter

- Glynis Johns, actress

- Gé Korsten, opera tenor and actor

- Anneline Kriel, Miss South Africa 1974 & Miss World 1974

- Paul Kruger, president of the South African Republic

- Michael Levitt, Nobel prizewinning biophysicist

- Thomas Madigage, soccer player

- Formula 1driver

- Vusi Mahlasela, singer/songwriter

- Justice Mahomed, former Chief Justice of South Africa, co-authored the constitution of Namibia

- Magnus Malan, Minister of Defence in the cabinet of President P. W. Botha

- Eugène Marais, lawyer, naturalist, poet and writer

- Sammy Marks, entrepreneur

- Herman Mashaba, the former Mayor of Johannesburg

- Thulasizwe Mbuyane, soccer player

- Karin Melis Mey, athlete

- Marc Milligan, cricketer

- Tim Modise, journalist, TV and radio presenter

- Lucas Moripe, soccer player (Pretoria Callies FC)

- Chris Morris, cricketer

- Michelle Mosalakae, actress and theatre director

- Es'kia Mphahlele, writer, educator, artist and activist celebrated as the Father of African Humanism

- Helene Muller, athlete

- Elon Musk, entrepreneur and business magnate

- Kimbal Musk, entrepreneur

- Franco Naudé, rugby union player

- Sean Nowak, cricketer

- Micki Pistorius, profiler and author

- Oscar Pistorius, athlete and convicted murderer

- Faf du Plessis, cricketer

- Louis Hendrik Potgieter, member of Dschinghis Khanpop band

- Austin Stevens, herpetologist, wildlife photographer, film maker and author

- Arnold Vosloo, actor

- Casper de Vries, comedian

- Joost van der Westhuizen, rugby union player

- Anton van Wouw, sculptor and artist

- A-Reece, rapper

- DJ Maphorisa, DJ and record producer

- 25k, rapper

- Dricus du Plessis, MMA fighter

- Asleigh Moolman, cycliste

Places of interest

This section is in prose. is available. (December 2016) |

- Pretoria National Botanical Garden, a botanical garden containing a massive collection of native flora.

- The National Zoological Gardens of South Africa, the premier zoological gardens of South Africa.

- Church Square, the historical governmental centre of the South African Republic.

- Union Buildings, the executive branch of the South African government.

- Mahlamba Ndlopfu, the official residence of the President of South Africa.

- Marabastad, a historical shopping district for non-whites during Apartheid.

- Menlyn Park, shopping area.

- Voortrekker Monument, a historical complex dedicated to the Great Trek.

- Hatfield Square, the main student relaxation district.

- Pretoria railway station, a historical landmark and departure point for metrorail and Gautrain trains.

- Freedom Park, a historical complex dedicated to the end of Apartheid and the fallen soldiers of South Africa after 1994.

- Boer Wars.

- State Theatre, South Africa, the premier national performing arts complex.

- Government House, Pretoria.

Nature reserves

- Chamberlain Bird Sanctuary

- Faerie Glen Nature Reserve

- Groenkloof Nature Reserve

- Moreletaspruit Nature Reserve

- Rietvlei Nature Reserve

- Roodeplaat Dam Provincial Nature Reserve

- Wonderboom Nature Reserve

See also

- Sir Herbert Baker

- Houses of Parliament, Cape Town

- Pretoria Wireless Users Group—a free, non-profit, community wireless network in Pretoria

- Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa

References

- ^ a b c d "Pretoria, Main Place 799035 from Census 2011". Census 2011. Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ a b "City of Tshwane, Metropolitan Municipality 799 from Census 2011". Census 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Gauteng's Human Development Index" (PDF). Gauteng City-Region Observatory. 2013. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Global city GDP 2011". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b "Pretoria | national administrative capital, South Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "South Africa at a glance". South African Government. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Raper, Peter E. (1987). Dictionary of Southern African Place Names. Internet Archive. p. 373. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "10 SA city nicknames, and why they're called that". News24. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "South Africa's provinces: Gauteng". Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ South African History Online, [1] Archived 16 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 2011]

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 54

- ^ Tools, Free Map. "Elevation Finder". Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ GHCN climate data, 30-year climate average 1979–2008, Goddard Institute of Space Studies

- ^ "South African Weather Service - Regional Weather and Climate of South Africa: Gauteng" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Pretoria Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Pretoria (Wetteramt), Transvaal / Südafrika" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ "Climate data for Pretoria". South African Weather Service. June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Population, according to the 2001 Census, of the Pretoria "main place" Archived 28 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Population, according to the 2007 Community Survey Archived 25 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, of the City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality after the 2011 annexation of the Metsweding District Municipality.

- ^ tinashe (1 June 2012). "Transfer of the Indian community of Pretoria to Laudium ordered". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "South African Reserve Bank Building, Pretoria | Building 103551". Pretoria /: Emporis. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "National Botanical Gardens". SA-Venues. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Boshoff, Dawie (March–April 1990). "Jakarandastad vier fees". Suid-Afrikaanse Panorama. 35 (2): 73–75.

- ^ "The seven-year long construction of Delagoa Bay railway line starts". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Rovos Rail website". Rovos.co.za. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Capital Park". Rovos Rail. Archived from the original on 9 September 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "New Departure Point – Important note!". Friends of the Rail. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "Tshwane Bus Booklet". Archived from the original on 28 May 2010.

- ^ Ditsele & Mann 2014

- ^ "Exhibitions". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Ditsong Museums Of South Africa". Ditsong.org.za. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Traditional & Folk Songs with Chords: Marching To Pretoria". Traditionalmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ traditionalmusic.co.uk, op. cit.

- ^ ""'I Am the Walrus' Lyrics," Shmoop: We Speak Student". Shmoop.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Pretoria Art Museum – Pretoria Attractions – Gauteng Conference Centre Midrand". Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Theatres in Pretoria". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Madiba's Journey – South African Tourism". Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "World's largest statue of Mandela unveiled". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Home". Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Premier Soccer League (13 May 2012). "Tuks secure Premiership promotion – SuperSport – Football". SuperSport. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "AmaTuks make it to top flight". Sowetan LIVE. 10 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "University of Pretoria – Highlands Park Preview: Relegated AmaTuks eye consolation win | Goal.com". www.goal.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "魁斗财经". www.ptbcc.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ "Getting to know Africa's flashy basketball arenas". FIBA. 2 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Britannica, SouthAfrica Archived 29 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 7 July 2019

- ^ "Support Association for Zionism – South African Jewry: History of Pretoria Jewry". Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ a b Church Square, the Old Synagogue and the Old Government Printing Work, Three historic places for testing strategic intervention University of Pretoria. 2015

- ^ "En daar verrys toe 'n Boeddhiste-sentrum". Pretoria Moot Rekord: 5. 24 April 2015.

- ^ Van Zyl, Seugnet (15 April 2015). "Boere-Boeddhis begin sentrum in Pretoria". Netwerk24. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Bodel, J.D.; 'The Coat of Arms and Other Heraldic Symbols of the City of Pretoria' in Pretoriana (November 1989).

- ^ Transvaal Official Gazette 2372 (11 March 1953).

- ^ http://www.national.archsrch.gov.za[permanent dead link]

- ^ 'Nuwe Standswapen' in Toria (July 1989).

- ^ "University of Pretoria". Times Higher Education. 13 November 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "SA Universities Retrieved 21 January 2011". Universityworldnews.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "About Veterinary Science > University of Pretoria". Web.up.ac.za. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Wits Business School". MBA.co.za. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Retrieved 20 March 2010". Mba.co.za. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "UP in a Nutshell 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Profile of the". CSIR. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "contact us". Army.mil.za. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Google Maps". Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ a b Col (Ret) Lionel Crook. "South African Gunner" (PDF). rfdiv.mil.za. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "Pretoria Regiment". Saarmourassociation.co.za. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "SA Army Signal Formation". Army.mil.za. 19 August 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "The South African Air Force". Saairforce.co.za. Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Pretoria name change is approved". BBC News. 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "SABC pulls 'Tshwane city' ads". News24.com. 11 April 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Independent Online. "SA capital advert row sparks ad-alert threat, IOL". Iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Media can't place Tshwane ads, FIN24". Fin24.co.za. Retrieved 3 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Down with Pretoria signs!: South Africa: Politics". News24. 2 August 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Wilson Johwa. "Mashatile postpones name changes after 'technicality'". Businessday.co.za. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "AfriForum to fight for Pretoria name". Timeslive.co.za. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Independent Online. "Pretoria name change rethink". Iol.co.za. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Pretoria/Tshwane delayed". Jacarandafm.com. 2 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Xingwana retracts Pretoria name change". Politicsweb.co.za. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "It's officially Pretoria. iafrica.com". News.iafrica.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Pretoria is Pretoria again – for now". Jacarandafm.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Government policy.'Leadership'". Leadershiponline.co.za. 23 March 2010. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Tshwane Royals: 'Change Pretoria for benefit of all'". Timeslive.co.za. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Pretoria will become Tshwane – mayor". News24. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Old cities, new names | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Pretoria of Tshwane? Minister weet self nie". Beeld. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Bakının qardaşlaşdığı şəhərlər - SİYAHI". modern.az (in Azerbaijani). 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Care-i cel mai… înfrățit oraș din România? Care-i cu americanii, care-i cu rușii? Și care-i înfrățit cu Timișoara…". banatulazi.ro (in Romanian). Banatul Azi. 6 August 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Sister Cities". citybyo.co.zw. Bulawayo. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Перелік міст, з якими Києвом підписані документи про поріднення, дружбу, співробітництво, партнерство" (PDF). kyivcity.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Kyiv. 15 February 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "International Links". mccpl.mu. Port Louis. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "International Sister Cities". tcc.gov.tw. Taipei. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "گذری بر خواهرخوانده تهران در شرق اروپا". isna.ir (in Persian). Iranian Students' News Agency. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "DC Sister Cities". os.dc.gov. Office of the Secretary, Washington DC. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

External links

- City of Tshwane; Metropolitan Municipality official website

- Discover Tshwane; Metropolitan Municipality tourism website

- 25503669 Pretoria on OpenStreetMap