Tick-borne encephalitis virus

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| |

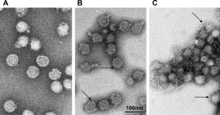

| TBEV at different pH levels | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Flasuviricetes |

| Order: | Amarillovirales |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Flavivirus |

| Species: | Tick-borne encephalitis virus

|

| Strains | |

| |

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) is a positive-strand RNA virus associated with tick-borne encephalitis in the genus Flavivirus.

Classification

Taxonomy

TBEV is a member of the genus

Subtypes

TBEV has three subtypes:

- Western European subtype (formerly Central European encephalitis virus, CEEV; principal tick vector: Ixodes ricinus);

- Siberian subtype (formerly West Siberian virus; principal tick vector: Ixodes persulcatus);

- Far Eastern subtype (formerly Russian Spring Summer encephalitis virus, RSSEV; principal tick vector: Ixodes persulcatus).[2]

The reference strain is the Sofjin strain.[3]

Virology

Structure

TBEV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, contained in a 40-60 nm spherical, enveloped capsid.[1] The TBEV genome is approximately 11kb in size, which contains a 5' cap, a single open reading frame with 3' and 5' UTRs, and is without polyadenylation.[1] Like other flaviviruses,[4] the TBEV genome codes for ten viral proteins, three structural, and seven nonstructural.[5][1]

The structural proteins are C (

Viral genetic determinants for pathogenicity

The envelope protein is involved in receptor-binding and neurovirulence, where increased glycosaminoglycan-binding affinity attenuates neuroinvasiveness.[6] The conformation of the E protein during viral particle secretion is influenced by glycosylation as well. [7] The immunogenicity of TBEV NS1 has been demonstrated, showcasing its ability to trigger oxidative stress and elicit the expression of immunoproteasome subunits. Additionally, it has been observed to stimulate the production of cytokines.[8] The NS5 protein has interferon antagonist activity as it downregulates the expression of IFN receptor subunit. Non structural protein 5 (NS5) affects neuropathogenesis by attenuation of neurite outgrowth. Untranslated region 3 (UTR3) and UTR 5 affect genomic RNA cyclization and replication, and viral RNA transport in dendrites, which impacts neurogenesis and synaptic communication.[6]

Life cycle

Transmission

Infection of the

Replication

In humans, the infection begins in the skin (with the exception of food-borne cases, about 1% of infections) at the site of the bite of an infected tick, where Langerhans cells and macrophages in the skin are preferentially targeted.[5] TBEV envelope (E) proteins recognize heparan sulfate (and likely other receptors) on the host cell surface and are endocytosed via the clathrin mediated pathway. Acidification of the late endosome triggers a conformational change in the E proteins, resulting in fusion, followed by uncoating, and release of the single-stranded RNA genome into the cytoplasm.[11][1]

The viral polyprotein is translated and inserts into the ER membrane, where it is processed on the cytosolic side by host peptidases and in the lumen by viral enzyme action. The viral proteins C, NS3, and NS5 are cleaved into the cytosol (though NS3 can complex with NS2B or NS4A to perform proteolytic or helicase activity), while the remaining nonstructural proteins alter the structure of the ER membrane. This altered membrane permits the assembly of replication complexes, where the viral genome is replicated by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, NS5.[11][5]

Newly replicated viral RNA genomes are then packaged by the C proteins while on the cytosolic side of the ER membrane, forming the immature nucleocapsid, and gain E and PrM proteins, arranged as a heterodimer, during budding into the lumen of the ER. The immature virion is spiky and geometric in comparison to the mature particle. The particle passes through the golgi apparatus and trans-golgi network, under increasingly acidic conditions, by which the virion matures with cleavage of the Pr segment from the M protein and formation fusion competent E protein homodimers. Though the cleaved Pr segment remains associated with protein complex until exit.[1][11]

The virus is released from the host cell upon fusion of the transport vesicle with the host cell membrane, the cleaved Pr now segments dissociate, resulting in a fully mature, infectious virus.[1][11] However, partially mature and immature viruses are sometimes released as well; immature viruses are noninfectious as the E proteins are not fusion competent, partially mature viruses are still capable of infection.[11]

Pathogenesis and immune response

With the exception of food-borne cases, infection begins in the skin at the site of the tick bite. Skin

The draining lymph node can also serve as a viral amplification site, from where TBEV gains systemic access. This viremic stage corresponds to the first symptomatic phase in the prototypical biphasic pattern of tick-borne encephalitis.[1] TBEV has a strong preference for neuronal tissue, and is neuroinvasive.[13] The initial viremic stage allows access to a number of the preferential tissues. However, the exact mechanism by which TBEV crosses into the central nervous system (CNS) is unclear.[13][12][1] There are several proposed mechanism for TBEV breaching the blood-brain barrier (BBB): 1)The "Trojan Horse" mechanism, whereby TBEV gains access to the CNS while infecting an immune cell that passes through the BBB;[12][5][13] 2) Disruption and increased permeability of the BBB by immune immune cytokines;[13] 3) Via infection of the olfactory neurons;[5] 4) Via retrograde transport along peripheral nerves to the CNS;[5] 5) Infection of the cells that make up part of the BBB.[5][12]

CNS infection brings on the second phase in the classic biphasic infection pattern associated with the European subtype. CNS disease is immunopathological; release of inflammatory cytokines coupled with the action of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and possibly NK cells results in inflammation and apoptosis of infected cells that is responsible for many of the CNS symptoms.[12][13]

Humoral response

TBEV specific IgM and IgG antibodies are produced in response to infection.[1] IgM antibodies appear and peak first, as well as reaching higher levels, and typically dissipate in about 1.5 months post infection, though there exists considerable variation from patient to patient. IgG levels peak at about 6 weeks after the appearance of CNS symptoms, then decline slightly but do not dissipate, likely conferring life long immunity to the patient.[1][5]

Evolution

The ancestor of the extant strains appears to have separated into several clades approximately 2750 years ago.[14] The Siberian and Far Eastern subtypes diverged about 2250 years ago. A second analysis suggests an earlier date of evolution (3300 years ago) with a rapid increase in the number of strains starting around 300 years ago.[15] Different strains of the virus have been transmitted at least three times into Japan between 260–430 years ago.[16][17] The strains circulating in Latvia appear to have originated from both Russia and Western Europe[18] while those in Estonia appear to have originated in Russia.[19] The Lithuanian strains appear to be related to those from Western Europe.[20] Phylogenetic analysis indicates that the European and Siberian TBEV sub-types are closely related while the Far-eastern sub-type is closer to the Louping Ill Virus.[1] However, in antigenic relatedness, based on the E, NS3, and NS5 proteins, all three sub-types are highly similar, and Louping Ill virus is the closest relative outside the collective TBEV group.[21]

History

Though the first description of what may have been TBE appears in records in the 1700s in Scandinavia,[13] identification of the TBEV virus occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1930s.[22] The investigation began due to an outbreak of what was believed to be Japanese Encephalitis ("Summer encephalitis"), among Soviet troops stationed along the border with the Japanese empire (present day People's Republic of China), near the Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk. The expedition was led by virologist Lev A. Zilber, who assembled a team of twenty young scientists in a number of related fields such as acarology, microbiology, neurology, and epidemiology.[23][22] The expedition arrived in Khabarovsk on May 15, 1937, and divided into squads, Northern-led by Elizabeth N. Levkovich and working in the Khabarovski Krai- and Southern-led by Alexandra D. Sheboldaeva, working in the Primorski Krai.[22]

Inside the month of May, the expedition had identified ticks as the likely vector, collected

The expedition returned in mid-August and in October 1937 Zilber and Sheboldova were arrested, falsely accused of spreading Japanese encephalitis. Expedition epidemiologist Tamara M. Safonov, was arrested the following January for protesting the charges against Zilber and Sheboldova. As a consequence of the arrests, one of the important initial works was published under the authorship of expedition acarologist, Vasily S. Mironov. Zilber was released in 1939 and managed to restore, along with Sheboldova, co-authorship on this initial work; however, Safanov and Sheboldova (who was not released) spent 18 years in labor camps.[22][23]

References

- ^ PMID 19420159.

- ISBN 978-1-55581-238-6.

- S2CID 12587373.

- S2CID 208789595.

- ^ S2CID 73414822.

- ^ PMID 30674746.

- PMID 23824303.

- PMID 36674524.

- ^ PMID 8158611.

- PMID 12641208.

- ^ PMID 29958443.

- ^ S2CID 195787988.

- ^ PMID 30319632.

- S2CID 18500235.

- PMID 22205716.

- PMID 17660689.

- PMID 11326122.

- S2CID 22860154.

- S2CID 28491834.

- S2CID 38061544.

- S2CID 150118109.

- ^ PMID 28526419.

- ^ PMID 29559213.

External links

- Encephalitis+Viruses,+Tick-Borne at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Tick-borne encephalitis at World Health Organization

- The TBE Book 4th Edition,Gerhard Dobler, Wilhelm Erber, Michael Bröker, Heinz-Josef Schmitt, Global Health Press,May 25, 2021 -pp 386pp