Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 July 1843 |

| Died | 21 January 1926 (aged 82) |

| Alma mater | University of Pavia |

| Known for | Golgi's method Golgi apparatus Golgi tendon organ Golgi cell Golgi cycles Reticular theory Radial glial cell Perineuronal net |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1906) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Pathology Neuroscience |

| Doctoral advisor | Cesare Lombroso |

| Doctoral students | Antonio Pensa |

Camillo Golgi (Italian:

Golgi and the Spanish biologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal were jointly given the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906 "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system".[2]

Biography

Camillo Golgi was born on 7 July 1843 in the village of Corteno near Brescia, in the

In 1867, he resumed his academic study under the supervision of

Financial pressure prompted him to join the Hospital of the Chronically Ill (Pio Luogo degli Incurabili) in

Personal life

Golgi and his wife Lina Aletti had no children, and they adopted Golgi's niece Carolina.[6]

Golgi was irreligious in his later life and became an agnostic atheist. One of his former students attempted an unsuccessful deathbed conversion on him.[9][10]

Contributions

Black reaction or Golgi's staining

The

I am delighted that I have found a new reaction to demonstrate, even to the blind, the structure of the interstitial stroma of the cerebral cortex.

His discovery was published in the Gazzeta Medica Italiani on 2 August 1873.[12]

Nervous system

In 1871, a German anatomist

In addition to this, Golgi was the first to give clear descriptions of the structure of the

Kidney

Golgi studied kidney function during 1882 to 1889. In 1882, he published his observations on the mechanism of

Malaria

A French Army physician

Cell organelle

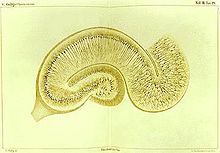

An organelle in eukaryotic cells now known as Golgi apparatus or Golgi complex, or sometimes simply as Golgi, was discovered by Camillo Golgi.[22] Golgi modified his black reaction using osmium dichromate solution with which he stained the nerve cells (Purkinje cells) of the cerebellum of a barn owl.[23] He noticed thread-like networks inside the cells and named them apparato reticolare interno (internal reticular apparatus). Recognising them to be unique cellular components, he presented his discovery before the Medical-Surgical Society of Pavia in April 1898.[24] After the same was confirmed by his assistant Emilio Veratti, he published it in the Bollettino della Società medico-chirurgica di Pavia.[25] However, most scientists disputed his discovery as nothing but a staining artefact. Their microscopes were not powerful enough to identify the organelles. By the 1930s, Golgi's description was largely rejected.[23] It was only firmly established 50 years after its discovery, when electron microscopes were developed.[26]

Awards and legacy

Golgi, together with

Monuments in Pavia

In Pavia several landmarks stand as Golgi's memory.

- A marble statue, in a yard of the old buildings of the University of Pavia, at N.65 of the central "Strada Nuova". On the basement, there is the following inscription in Italian language: "Camillo Golgi / patologo sommo / della scienza istologica / antesignano e maestro / la segreta struttura / del tessuto nervoso / con intenta vigilia / sorprese e descrisse / qui operò / qui vive / guida e luce ai venturi / MDCCCXLIII – MCMXXVI" (Camillo Golgi / outstanding pathologist / of histological science / precursor and master / the secret structure / of the nervous tissue / with strenuous effort / discovered and described / here he worked / here he lives / here he guides and enlightens future scholars / 1843 – 1926).

- "Golgi’s home", also in Strada Nuova, at N.77, a few hundreds meters away from the University, just in front to the historical "Teatro Fraschini". It is the home in which Golgi spent the most of his family life, with his wife Lina.

- Golgi's tomb is in the Monumental Cemetery of Pavia (viale San Giovannino), along the central lane, just before the big monument to the fallen of the First World War. It is a very simple granite grave, with a bronze medallion representing the scientist's profile. Near Golgi's tomb, apart from his wife, two other important Italian medical scientists are buried: Bartolomeo Panizza and Adelchi Negri.

- Golgi's museum was created in 2012, in the ancient Palazzo Botta of the University of Pavia at N.10 of Piazza Antoniotto Botta reconstructs the study of Camillo Golgi and its laboratories with furniture and original instruments.[29]

Eponyms

- The organelle Golgi complex

- The sensory receptor Golgi tendon organ

- Golgi's method or Golgi stain, a nervous tissue staining technique

- The enzyme Golgi alpha-mannosidase II

- Golgi cells of the cerebellum

- Golgi Inerve cells (with long axons)

- Golgi IInerve cells (with short or no axons)

- Golgi (crater), a lunar impact crater [30]

- Minor planet 6875 Golgi is named after him.[31]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-19-972969-2.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Cimino, Guido (2001). "GOLGI, Camillo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 57.

- .

- ^ PMID 11624293.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-385158-1.

- S2CID 7920555.

- ^ Zanobio, Bruno. "Camillo Golgi facts, information, pictures". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852444-1. It was probably during this period that Golgi became agnostic (or even frankly atheistic), remaining for the rest of his life completely alien to the religious experience.

- ^ Rapport, Richard L. Nerve Endings: The Discovery of the Synapse. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005. Print.

- PMID 16995603.

- PMID 25798090.

- ^ a b Marina Bentivoglio (20 April 1998). "Life and Discoveries of Camillo Golgi". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- PMID 11640243.

- S2CID 11871228.

- PMID 23870749.

- ^ PMID 9489532.

- S2CID 29666037.

- ^ Golgi C. (1889). "Sul ciclo evolutivo dei parassiti malarici nella febbre terzana : diagnosi differenziale tra i parassiti endoglobulari malarici della terzana e quelli della quartana" [On the cycle of development of malarial parasites in tertian fever: differential diagnosis between the intracellular parasites of tertian and quartant fever]. Archivio per le Scienza Mediche. 13: 173–196.

- PMID 22550559.

- PMID 20205846.

- PMID 11624302.

- ^ S2CID 36117803.

- S2CID 23309035.

- S2CID 9679562.

- S2CID 31879493.

- ^ GOLGI Camillo Archived 7 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Italian senate website

- ^ "C. Golgi (1844–1926)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Spizzi, Dante. "Museo Camillo Golgi". museocamillogolgi.unipv.eu (in Italian). Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Golgi crater". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "(6875) Golgi = 1994 NG1 = 1934 QB = 1953 RK = 1977 DH2 = 1991 RT30 = 4643 T-1 = T/4643 T-1". Minor planet center.

Further reading

- Mazzarello, Paolo (2010), Golgi: A Biography of the Founder of Modern Neuroscience, translated by Badiani, Aldo; Buchtel, Henry A., New York: ISBN 978-0-19-533784-6

- Mironov, Alexander A.; Margit, Pavelka (2006). The Golgi Apparatus State of Art After 110 Years of Camillo's Discovery. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 3-211-76310-4.

- Morré, D. James; Mollenhauer, Hilton H. (2009). The Golgi Apparatus: The First 100 Years. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-74347-9.

- De Carlos, Juan A; Borrell, José (2007), "A historical reflection of the contributions of Cajal and Golgi to the foundations of neuroscience.", Brain Research Reviews, vol. 55, no. 1 (published August 2007), pp. 8–16, S2CID 7266966

- Muscatello, Umberto (2007), "Golgi's contribution to medicine.", Brain Research Reviews, vol. 55, no. 1 (published August 2007), pp. 3–7, S2CID 41680914

- Kruger, Lawrence (2007), "The sensory neuron and the triumph of Camillo Golgi", Brain Research Reviews, vol. 55, no. 2 (published October 2007), pp. 406–10, S2CID 32486297

- Fabene, P F; Bentivoglio, M (1998), "1898–1998: Camillo Golgi and "the Golgi": one hundred years of terminological clones.", Brain Res. Bull., vol. 47, no. 3 (published October 1998), pp. 195–8, S2CID 208785591

- Mironov, A A; Komissarchik, Ia Iu; Mironov, A A; Snigirevskaia, E S; Luini, A (1998), "[Current concept of structure and function of the Golgi apparatus. On the 100-anniversary of the discovery by Camillo Golgi]", Tsitologiia, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 483–96, PMID 9778732

- Farquhar, M G; Palade, G E (1998), "The Golgi apparatus: 100 years of progress and controversy.", Trends Cell Biol., vol. 8, no. 1 (published January 1998), pp. 2–10, PMID 9695800

External links

- Life and Discoveries of Camillo Golgi

- Camillo Golgi on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1906 The Neuron Doctrine – Theory and Facts

- Some places and memories related to Camillo Golgi

- The museum in Corteno, now called Corteno Golgi, dedicated to Golgi. Includes a gallery of images of his birthplace.

- The Museum Camillo Golgi in Pavia

- Biography at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Biography at Encyclopedia.com

- Profile at Whonamedit?

- IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Foundation Archived 25 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Maggiore della Carità di Novara