Dennis Gabor

Dennis Gabor CBE FRS | |

|---|---|

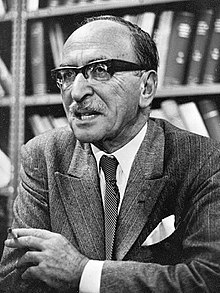

Gabor, c. 1971 | |

| Born | Dénes Günszberg 5 June 1900 |

| Died | 9 February 1979 (aged 78) London, England |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse |

Marjorie Louise Butler

(m. 1936) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | |

Dennis Gabor

Life and career

Gabor was born as Günszberg Dénes, into a Jewish family in Budapest, Hungary. In 1900, his family converted to Lutheranism.[15] Dennis was the first-born son of Günszberg Bernát and Jakobovits Adél. Despite having a religious background, religion played a minor role in his later life and he considered himself agnostic.[16] In 1902, the family received permission to change their surname from Günszberg to Gábor. He served with the Hungarian artillery in northern Italy during World War I.[17]

He began his studies in engineering at the

In 1933 Gabor fled from

Gabor's research focused on electron inputs and outputs, which led him to the invention of holography.[18] The basic idea was that for perfect optical imaging, the total of all the information has to be used; not only the amplitude, as in usual optical imaging, but also the phase. In this manner a complete holo-spatial picture can be obtained.[18] Gabor published his theories of holography in a series of papers between 1946 and 1951.[18]

Gabor also researched how human beings communicate and hear; the result of his investigations was the theory of

In 1948 Gabor moved from Rugby to

As part of his many developments related to CRTs, in 1958 Gabor patented a new

In 1963 Gabor published Inventing the Future which discussed the three major threats Gabor saw to modern society: war, overpopulation and the Age of Leisure. The book contained the now well-known expression that "the future cannot be predicted, but futures can be invented." Reviewer

In 1971 he was the single recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics with the motivation "for his invention and development of the holographic method"[24] and presented the history of the development of holography from 1948 in his Nobel lecture.

While spending much of his retirement in Italy at Lavinio Rome, he remained connected with Imperial College as a senior research fellow and also became staff scientist of CBS Laboratories, in Stamford, Connecticut; there, he collaborated with his lifelong friend, CBS Labs' president Dr. Peter C. Goldmark in many new schemes of communication and display. One of Imperial College's new halls of residence in Prince's Gardens, Knightsbridge is named Gabor Hall in honour of Gabor's contribution to Imperial College. He developed an interest in social analysis and published The Mature Society: a view of the future in 1972.[25] He also joined the Club of Rome and supervised a working group studying energy sources and technical change. The findings of this group was published in the report Beyond the Age of Waste in 1978, a report which was an early warning of several issues that only later received widespread attention.[26]

Following the rapid development of lasers and a wide variety of holographic applications (e.g., art, information storage, and the recognition of patterns), Gabor achieved acknowledged success and worldwide attention during his lifetime.[18] He received numerous awards besides the Nobel Prize.

Gabor died in a nursing home in South Kensington, London, on 9 February 1979. In 2006 a blue plaque was put up on No. 79 Queen's Gate in Kensington, where he lived from 1949 until the early 1960s.[27]

Personal life

On 8 August 1936 he married Marjorie Louise Butler. They did not have any children.

Publications

- The Electron Microscope (1934)

- Inventing the Future (1963)

- Innovations: Scientific, Technological, and Social (1970)

- The Mature Society (1972)

- Proper Priorities of Science and Technology (1972)

- Beyond the Age of Waste: A Report to the Club of Rome (1979, with U. Colombo, A. King en R. Galli)

Awards and honors

- 1956 – Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS)[1]

- 1964 – Honorary Member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- 1964 – D.Sc., University of London

- 1967 – Young Medal and Prize, for distinguished research in the field of optics

- 1967 – Columbus Award of the International Institute for Communications, Genoa

- 1968 – The first

- 1968 – Rumford Medal of the Royal Society

- 1970 – Honorary Doctorate, University of Southampton

- 1970 – Medal of Honor of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- 1970 – Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)

- 1971 – Nobel Prize in Physics, for his invention and development of the holographic method

- 1971 – Honorary Doctorate, Delft University of Technology

- 1972 – Holweck Prize of the Société Française de Physique

- 1983 – the

- 1989 – the Royal Society of London began issuing the Gabor Medal for "acknowledged distinction of interdisciplinary work between the life sciences with other disciplines".[30]

- 1992 – , is named after Gabor.

- 1993 – the NOVOFER Foundation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences established its annual International Dennis Gabor Award, for outstanding young scientists researching in the fields of physics and applied technology.

- 2000 – the asteroid 72071 Gáboris named after Gabor.

- 2008 – the Institute of Physics renamed its Duddell Medal and Prize, established in 1923, into the Dennis Gabor Medal and Prize.

- 2009 – Imperial College London opened the Gabor Hall.[31]

- Dennis-Gabor-Straße in Potsdam is named in his honour and is the location of the Potsdamer Centrum für Technologie.

In popular culture

- On 5 June 2010, the logo for the Google website was drawn to resemble a hologram in honour of Dennis Gabor's 110th birthday.[32]

- In David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest, Hal suggests that "Dennis Gabor may very well have been the Antichrist."[33]

See also

- Adaptive Gabor representation

- Gabor expansion

- Gabor frame

- Microsound

- Meniscus corrector

- Gábor Dénes College

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

References

- ^ S2CID 53732181.

- ^ Shewchuck, S. (December 1952). "SUMMARY OF RESEARCH PROGRESS MEETINGS OF OCT. 16, 23 AND 30, 1952". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: 3.

- ^ "Gabor". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Gabor". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Gabor, Dennis". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Gabor". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- PMID 379651.

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1944). The electron microscope : Its development, present performance and future possibilities. London. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1963). Inventing the Future. London : Secker & Warburg. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1970). Innovations: Scientific, Technological, and Social. London : Oxford University Press. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1972). The Mature Society. A View of the Future. London : Secker & Warburg. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Gabor, Dennis; and Colombo, Umberto (1978). Beyond the Age of Waste: A Report to the Club of Rome. Oxford : Pergamon Press. [ISBN missing]

- ^ "GÁBOR DÉNES". sztnh.gov.hu (in Hungarian). Szellemi Tulajdon Nemzeti Hivatala. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Gábor Dénes". itf.njszt.hu (in Hungarian). Neumann János Számítógép-tudományi Társaság. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Dennis Gabor Biography. Bookrags.com (2 November 2010). Retrieved on 7 September 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7876-1753-0.

Although Gabor's family became Lutherans in 1918, religion appeared to play a minor role in his life. He maintained his church affiliation through his adult years but characterized himself as a "benevolent agnostic".

- ISBN 978-0-19-857122-3.

- ^ ISSN 0015-3257. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ISBN 0-8242-0756-4.

- British Thomson-Houston Company, published 1947

- ISBN 1-57647-079-2.

- ^ Adamson, Ian; Kennedy, Richard (1986). Sinclair and the 'sunrise' Technology. Penguin. pp. 91–92.

- ^ "We Cannot Predict the Future, But We Can Invent It". quoteinvestigator.com. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1971". nobelprize.org.

- ^ IEEE Global History Network (2011). "Dennis Gabor". IEEE History Center. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ISBN 0-08-021834-2.

- ^ "Blue Plaque for Dennis Gabor, inventor of Holograms". Government News. 1 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Franklin Laureate Database – Albert A. Michelson Medal Laureates". Franklin Institute. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Dennis Gabor Award". SPIE. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "The Gabor Medal (1989)". Royal Society. 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Eastside Halls. imperial.ac.uk

- ^ "Dennis Gabor's birth celebrated by Google doodle". The Telegraph. London. 5 June 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ Wallace, David Foster (1996). "Infinite Jest". New York: Little, Brown and Co.: 12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- Dennis Gabor on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1970 Magnetism and the Local Molecular Field

- Nobel Prize presentation speech by Professor Erik Ingelstam of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Biography at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 July 2008)

- Works by or about Dennis Gabor at Internet Archive