Saint Sava

Ana | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | archbishop |

| Signature |  |

Saint Sava (

He is widely considered one of the most important figures of

Biography

Early life

Rastko (

Mount Athos

Upon arriving at Athos, Rastko entered the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery where he received the monastic name of Sava (Sabbas).[12] According to tradition, a Russian monk was his spiritual guide or mentor[10] and was said to have had earlier visited the Serbian court with other Athonite monks.[12] Sava then entered the Greek Vatopedi monastery, where he would stay for the next seven years, and became more closely acquainted with Greek theological and church-administrational literature. His father tried to persuade him to return to Serbia, but Sava was determined and replied, "You have accomplished all that a Christian sovereign should do; come now and join me in the true Christian life".[10] His young years at Athos had a significant influence on the formation of his personality, it was also here that he found models on which he would organize monastic and church life in Serbia.[16][17]

Stefan Nemanja took his son's advice

When Sava visited the Byzantine Emperor Alexios III Angelos at Constantinople, he mentioned the neglected and abandoned Hilandar, and asked the Emperor that he and his father be given the permit to restore the monastery and grant it to Vatopedi.[19] The Emperor approved, and sent a special letter and considerable gold to his friend Stefan Nemanja (monk Simeon).[19] Sava then addressed the Protos of Athos, asking them to support the effort so the monastery of Hilandar might become the haven for Serb monks.[19] All Athonite monasteries, except Vatopedi, accepted the proposal. In July 1198 Emperor Alexios III authored a charter which revoked the earlier decision, and instead not only granted Hilandar, but also the other abandoned monasteries in Mileis, to Simeon and Sava, to be a haven and shelter for Serb monks in Athos.[19] The restoration of Hilandar quickly began and Grand Prince Stefan sent money and other necessities, and issued the founding charter for Hilandar in 1199.[19]

Sava wrote a

As Nemanja had earlier (1196) decided to give the rule to

Enlightenment

Having spent 14 years in Mount Athos, Sava had extensive theological knowledge and spiritual power.

In 1217, archimandrite Sava left Studenica and returned to Mount Athos. His departure has been interpreted by a part of the historians as a reaction to his brother Stefan accepting the royal crown from Rome.[25] Stefan had just prior to this made a large switch in politics, marrying a Venetian noblewoman, and subsequently asked the Pope for a royal crown and political support.[27] With the establishment of the Latin Empire (1204), Rome had considerably increased its power in the Balkans. Stefan was crowned by a papal legate, becoming equal to the other kings, and was called "the First-Crowned King" of Serbia.[28][29]

Stefan's politics that led to the events of 1217 were somewhat in odds with the Serbian Orthodox tradition, represented by his brother, archimandrite Sava, who favored Eastern Orthodoxy and Byzantine ecclesiastical culture in Serbia. Though Sava left Serbia while talks were underway between Stefan and Rome (apparently due to disagreeing with Stefan's excessive reliance on Rome), he and his brother resumed their good relation after receiving the crown. It is possible that Sava did not agree with everything in his brother's international politics, however, his departure for Athos may also be interpreted as a preparation for obtaining the autocephaly (independence) of the Serbian Archbishopric.[25] His departure was planned, both Domentijan and Teodosije, Sava's biographers, stated that before leaving Studenica he appointed a new hegumen and "put the monastery in good, correct order, and enacted the new church constitution and monastic life order, to be held that way", after which he left Serbia.[25]

Autocephaly and church organization

The elevation of Serbia into a kingdom did not fully mark the independence of the country, according to that time's understanding, unless the same was achieved with its church. Rulers of such countries, with church bodies subordinated to Constantinople, were viewed as "rulers of lower status who stand under the top chief of the Orthodox Christian world – the Byzantine Emperor". Conditions in Serbia for autocephaly were largely met at the time, with a notable number of learned monks, regulated monastic life, stable church hierarchy, thus "its autocephaly, in a way, was only a question of time". It was important to Sava that the head of the Serbian church was appointed by Constantinople, and not Rome.[30]

On 15 August 1219, during the feast of the

From Nicaea, Archbishop Sava returned to Mount Athos, where he profusely donated to the monasteries.[25] In Hilandar, he addressed the question of administration: "he taught the hegumen especially how to, in every virtue, show himself as an example to others; and the brothers, once again, he taught how to listen to everything the hegumen said with the fear of God", as witnessed by Teodosije.[25] From Hilandar, Sava traveled to Thessaloniki, to the monastery of Philokalos, where he stayed for some time as a guest of the Metropolitan of Thessaloniki, Constantine the Mesopotamian, with whom he was a great friend ever since his youth.[25] His stay was of great benefit as he transcribed many works on law needed for his church.[37]

Upon his return to Serbia, he was engaged in the organization of the Serbian church, especially regarding the structure of bishoprics, those that were situated on locales at the sensitive border with the Roman Catholic West.

The organizational work of Sava was very energetic, and above all, the new organization was given a clear national character. The Greek bishop at Prizren was replaced by a Serbian, his disciple. This was not the only feature of his fighting spirit. The determination of the seats of the newly established bishoprics was also performed with especially state-religious intention. The Archbishopric was seated in the

First pilgrimage

After the crowning of his nephew

Second pilgrimage and death

After the throne change in 1234, when King Radoslav was succeeded by his brother Vladislav, Archbishop Sava began his second trip to the Holy Land.[46] Prior to this, Sava had appointed his loyal pupil Arsenije Sremac as his successor to the throne of the Serbian Archbishopric.[46] Domentijan says that Sava chose Arsenije through his "clairvoyance", with Teodosije stating further that he was chosen because Sava knew he was "evil-less and more just than others, prequalified in all, always fearing God and carefully keeps His commandments".[46] This move was wise and deliberate; still in his lifetime he chose himself a worthy successor because he knew that the further fate of the Serbian Church largely depended on the personality of the successor.[46]

Sava began his trip from

After touring the holy places in

As on all his destinations, he gave rich gifts to the churches and monasteries: "[he] gave also to the Bulgarian Patriarchate priestly honourable robes and golden books and candlesticks adorned with precious stones and pearls and other church vessels", as written by Teodosije.[49] Sava had after much work and many long trips arrived at Tarnovo a tired and sick man.[50] When the sickness took a hold of him and he saw that the end was near, he sent part of his entourage to Serbia with the gifts and everything he had bought with his blessing to give "to his children".[50] The eulogia consisted of four items.[51] Domentijan accounted that he died between Saturday and Sunday, most likely on 27 January [O.S. 14 January] 1235.[50]

Sava was respectfully buried at the

Legacy

Saint Sava is the protector of the Serb people: he is venerated as a protector of churches, families, schools and artisans.[54] His feast day is also venerated by Greeks, Bulgarians, Romanians and Russians.[54] Numerous toponyms and other testimonies, preserved to this day, convincingly speak of the prevalence of the cult of St. Sava.[54] St. Sava is regarded the father of Serbian education and literature; he authored the Life of St. Simeon (Stefan Nemanja, his father), the first Serbian hagiography.[54] He has been given various honorific titles, such as "Father" and "Enlightener".[b]

The Serb people built the cult of St. Sava based on the religious cult; many songs, tales and legends were created about his life, work, merit, goodness, fairness and wisdom, while his relics became a topic of national and ethnopolitical cult and focus of liberation ideas.[54] In 1840, at the suggestion of Atanasije Nikolić, the rector of the Lyceum, the feast of Saint Sava was chosen to celebrate Education every year. It was celebrated as a school holiday until 1945 when the communist authorities abolished it. In 1990, it was reintroduced as a school holiday.[55]

The Serbian Orthodox Church venerates saint Sava on January 27 [O.S. January 14].[54]

Biographies

The first, shorter, biography on St. Sava was written by his successor, Archbishop Arsenije.

Relics

The presence of the relics of St. Sava in Serbia had a church-religious and political significance, especially during the Ottoman period.Burning of relics

Churches dedicated to St. Sava

There are many temples (hramovi) dedicated to St. Sava. As early as the beginning of the 14th century, Serbian Archbishop

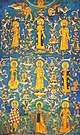

Visual arts

There are close to no Serbian churches that do not have a depiction of St. Sava.

St. Sava is depicted with St. Simeon on an icon from the 14th century which is held in the National Museum in Belgrade, and on an icon held in the National Museum in Bucharest.

Graphical illustrations of St. Sava are found in old Serbian printed books: Triode from the

Literature

Many Serbian poets have written poetry dedicated to St. Sava. These include Jovan Jovanović Zmaj's (1833–1904) Pod ikonom Svetog Save and Suze Svetog Save, Vojislav Ilić's (1860–1894) Sveti Sava and Srpkinjica, Milorad Popović Šapčanin's (1841–1895) Svetom Savi, Aleksa Šantić's (1868–1924) Pred ikonom Svetog Save, Pepeo Svetog Save, Sveti Sava na golgoti, Vojislav Ilić Mlađi's (1877–1944) Sveti Sava, Nikolaj Velimirović's (1881–1956) Svetitelju Savo, Reči Svetog Save and Pesma Svetom Savi, Milan Petrović's (1902–1963) Sveti Sava, Vasko Popa's (1922–1991) St. Sava's Journey, Momčilo Tešić's (1911–1992) Svetom Savi, Desanka Maksimović's (1898–1993) Savin monolog, Matija Bećković's (b. 1939) Priča o Svetom Savi, Mićo Jelić Grnović's (b. 1942) Uspavanka, and others.

Works

The earliest works of Sava were dedicated to ascetic and monastic life: the Karyes Typikon and Hilandar Typikon.[65] In their nature, they are Church law, based strictly on non-literary works, however, in them some moments came to expression of indirect importance for the establishment of an atmosphere in which Sava's original and in the narrow sense, literary works, came to exist.[65] In addition, characteristics of Sava's language and style come to light here, especially in those paragraphs which are his specific interpretations or independent supplements.[65]

- Karyes Typikon, written for the Karyes cell in 1199. It is basically a translation from a standard Greek ascetic typikon. It became a model for Serbian solitary or eremitical monasticism also outside of Mount Athos.[66]

- Hilandar Typikon, written for Hilandar in 1199. Compiled as a translation and adaptation of the introductory part of the Greek Theotokos Euergetis typikon from Constantinople. Sava only used some parts of that typikon, adding his own, different regulations tailored to the needs of Hilandar. He and his father had donated to the Euergetis monastery, and Sava stayed there on his trips to Constantinople, seemingly, he liked the order and way of life in this monastery. This typikon was to become the general managing order for other Serbian monasteries (with small modifications, Sava wrote the Studenica Typikon in 1208).[67] The Hilandar Typikon contains regulations for the spiritual life in the monastery and organization of various services of the monastic community (opštežića).[68]

The organization of the Serbian church with united areas was set on a completely new basis. The activity of major monasteries developed; caretaking of missionary work was put under the duty of the proto-priests (protopopovi). Legal regulations of the Serbian Church was constituted with a code of a new, independent, compilation of Sava – the Nomocanon or Krmčija; with this codification of Byzantine law, Serbia already at the beginning of the 13th century received a firm legal order and became a state of law, in which the rich Greek-Roman law heritage was continued.[69][70]

- Nomocanon (sr. Zakonopravilo) or Krmčija, most likely created in Thessaloniki in 1220, when Sava returned from Nicaea to Serbia, regarding the organization of the new, autocephalous Serbian church. It was a compilation of state ("civil") law and religious rules or canons, with interpretations of famous Byzantine canonists, who by themselves were a kind of source of law. As Byzantine nomocanons, with or without interpretation, the Serbian Nomocanon was a capital source and monument of law; in the medieval Serbian state, it was the source of the first order as a "divine right"; after it, legislations of Serbian rulers (including Dušan's Code) were created. Sava was the initiator of the creation of this compilation, while the translation was likely the work of various authors, older and contemporary to Sava. An important fact is that the choice of compilation in this nomocanon was unique: it is not preserved in Greek manuscript tradition. In the ecclesiastic term, it is very characteristic, due to its opposing of that period's views in effect on church-state relations in Byzantium, and restoring of some older conceptions with which the sovereignty of divine law is insisted on.[71]

His liturgical regulations include also Psaltir-holding laws (Ustav za držanje Psaltira), which he translated from Greek, or as possibly is the case with the Nomocanon, was only the initiator and organizer, and supervisor of the translation.

In the Hilandar Typikon, Sava included the Short Hagiography of St. Simeon Nemanja, which tells of Simeon's life between his arrival at Hilandar and death. It was written immediately after his death, in 1199 or 1200. The developed hagiography on St. Simeon was written in the introduction of the Studenica Typikon (1208).[76]

- Hagiography of St. Simeon, written in 1208 as a ktetor hagiography of the founder of Studenica.[76] It was made according to the rules of Byzantine literature.[76] The hagiography itself, biography of a saint, was one of the main prose genres in Byzantium.[76] Hagiographies were written to create or spread the cult of the saint, and communicated the qualities of and virtues of the person in question.[76] The work focused on the monastic character of Simeon, using biographical information as a subset to his renouncing of the throne, power and size in the world for the Kingdom of Heaven.[77] Simeon is portrayed as a dramatic example of renouncing earthly life, as a representative of basic evangelical teachings and foundations of these, especially of monastic spirituality.[77] His biographical pre-history (conquests and achievements) with praises are merged in the prelude, followed by his monastic feats and his death, ending with a prayer instead of praise.[77] The language is direct and simple, without excessive rhetorics, in which a close witness and companion, participant in the life of St. Simeon, is recognized (in Sava).[78] Milan Kašanin noted that "no old biography of ours is that little pompous and that little rhetorical, and that warm and humane as Nemanja's biography".[78]

Very few manuscripts of the works of St. Sava have survived.[79] Apart from the Karyes Typikon, of which copy, a scroll, is today held at Hilandar, it is believed that there are no original manuscript (authograph) of St. Sava.[79] The original of the Charter of Hilandar (1198) was lost in World War I.[79]

St. Sava is regarded the founder of the independent medieval Serbian literature.[80]

Ktetor

Sava founded and reconstructed churches and monasteries wherever he stayed.

Returning to Serbia in 1206, Sava continued his work. The Mother of God Church in Studenica was painted, and two hermitages near Studenica were endowed.

- Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos

- Karyes Typicon)

- Church of John the Apostle in Jerusalem

And many other churches across Serbia, as well.

|

|

-

Studenica

-

Mileševa

See also

- Serbian Orthodox Church

- Serbian Saints

- Eastern Orthodox Saints

- Order of St. Sava

- Only Unity Saves the Serbs

- John the Deacon

Annotations

- Alexis Vlasto[10]supports ca. 1174.