Hilandar

Хиландар Χιλανδαρίου | |

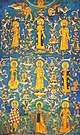

Virgin Mary) The Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple | |

| People | |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) | Saint Sava and Saint Symeon |

| Archbishop | Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople |

| Site | |

| Location | Mount Athos, Greece |

| Coordinates | 40°20′46″N 24°07′08″E / 40.346111°N 24.118889°E |

| Public access | Men only |

The Hilandar Monastery (Serbian Cyrillic: Манастир Хиландар, romanized: Manastir Hilandar, pronounced [xilǎndaːr], Greek: Μονή Χιλανδαρίου) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Serbian monastery there. It was founded in 1198 by Stefan Nemanja (Saint Symeon) and his son Saint Sava. St. Symeon was the former Grand Prince of Serbia (1166–1196) who upon relinquishing his throne took monastic vows and became an ordinary monk. He joined his son Saint Sava who was already in Mount Athos and who later became the first Archbishop of Serbia. Upon its foundation, the monastery became a focal point of the Serbian religious and cultural life,[1][2] as well as assumed the role of "the first Serbian university".[3] It is ranked fourth in the Athonite hierarchy of 20 sovereign monasteries.[4] The Mother of God through her Icon of the Three Hands (Trojeručica) is considered the monastery's abbess.[5]

The monastery contains about 45 working monks.[when?]

Etymology

The etymological meaning of "Hilandar" is probably derived from the Greek word

Founding

The monastery was founded in 1198; prompted by the

Upon securing Serbian authority within the monastery,

The Nemanjić period and late Byzantine Empire

After the

Consequently, Serbian

At the time of

Ottoman and modern period

The Byzantine Empire was conquered in the 15th century by the Ottoman Turks and their newly established Ottoman Empire. The Athonite monks tried to maintain functioning relations with the Ottoman sultans and following Murad II's occupation of Thessaloniki in 1430 they pledged their obedience to him.[22] Murad II left Mount Athos its self-rule and allocated for some remaining privileges. Hilandar retained its property rights and autonomy in the hinterland.[23] This was additionally confirmed and secured in 1457 by Sultan Mehmed II following the 1453 Fall of Constantinople. Thus, the Athonite independence was somewhat ensured.

In the second half of the 15th century, Hilandar moved to third place in the hierarchy of Athionite monasteries. It also became a refuge for Serbian monks seeking to evade the conflicts of the time. Following the fall of the

In the 17th century the number of Serbian monks dwindled, and the disastrous fire in 1722 saw a decline: in his account of 1745,

However, in 1913, Serbian presence on Athos was quite big and the Athonite protos was the Serbian representative of Hilandar.[31]

Contemporary

In the 1970s, the Greek government offered power grid installation to all of the monasteries on Mount Athos. The Holy Council of Mount Athos refused, and since then every monastery generates its own power, which is gained mostly from renewable energy sources. During the 1980s, electrification of the monastery of Hilandar took place, generating power mostly for lights and heating.

In 1990, Hilandar was converted from an

On March 4, 2004, there was a devastating fire at the Hilandar monastery, which destroyed much of the walled complex and all the wooden elements.[33] The library and the monastery's many historic icons were saved or otherwise untouched by the fire. Vast reconstruction efforts to restore Hilandar are underway.

Sacred objects

Among the numerous

The monastery also possesses the Wonderworking Icon of the

There are some 1200 Slavic manuscripts. Archives include 172 Greek and 154 Serbian documents from the medieval era, which provides a glimpse into the economic and social structure of the period.[21] The Serbian variant of Old Church Slavonic developed at the monastery thanks to its scriptorium.

See also

- Hilandar Research Library

- Miroslav Gospels

- Saint Sava

- Stefan Nemanja

References

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 38.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- ISBN 978-81-208-0990-1.

- ^ "The administration of Mount Athos". Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ^ Hilandar – The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity

- ^ a b Tibor Zivkovic - Charters of the Serbian rulers related to Kosovo and Metochia. p. 15

- ^ "За спас душе своје и прибежиште свом отачеству". Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- ^ "Хиландарски поседи и метоси у југозападној Србији (Кособу и метохији)". hilandar.info. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- ^ Vlasto, The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs, p. 219

- ^ "The Monastery of Hilandar". Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ Bogdanović 1997, Предговор, para. 13, Карејски типик

- ^ Bogdanović 1997, Предговор, para. 14

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "Miraculous Icon - The Virgin with three hands (Bogorodica Trojeručica)". hilandar.info. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ISBN 1139444085.

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b "Chilandar Monastery". orthodoxia.it.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 40.

- ^ ISBN 9780195046526.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 95.

- ^ Subotić 1998, p. 98.

- ^ Robert Payne, Nikita Romanoff, "Ivan the Terrible", Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 pp. 436

- ^ Subotić 1998, pp. 100–102.

- Zograf monastery.

- ^ "Хилендарски манастир" (in Bulgarian). Православието. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ Panagiotis Christou, "To Agion Oros", Patriarchal Institute of Patristic Studies, Epopteia ed., Athens, 1987 pp. 313-314

- ^ Dorobantu, Marius (2017-08-28). Hesychasm, the Jesus Prayer and the contemporary spiritual revival of Mount Athos (Master's thesis). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ Folić, Nađa Kurtović (2014). Consequences of a Wrong Decision: Case Study of Chilandar Monastery Fire. Structural Faults & Repair - 15th International Conference.

- ISBN 9780192511140.

Sources

- Dimitrije Bogdanović; Vojislav J. Đurić; Dejan Medaković; Miodrag Đorđević (1997). Chilandar. Monastery of Chilandar. ISBN 9788674131053.

- Miodrag B. Branković; Marin Brmbolić; Milorad Miljković; Verica Ristić (2006). Chilandar Monastery. Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture. ISBN 978-86-80879-48-2.

- ISBN 9781405142915.

- Branislav Cvetković (2002). Eight centuries of the Monastery of Chilandar at Mount Athos. Zavičajni muzej. ISBN 978-86-902543-2-3.

- Đurić, V.J. (1964) Fresques médiévales à Chilandar. in: Actes du XIIe Congrès international d'études Byzantines, Ochride, 1961, Beograd, 68

- ISBN 0472082604.

- Hostetter, W.T. (1998) In the heart of Hilandar: An interactive presentation of the frescoes in the main church of the Hilandar monastery of Mt. Athos. Belgrade, CD-ROM

- Rajko R. Karišić; Mihajlo Mitrović; Gordana Najčević (2003). Chilandar - unto ages of ages. R. R. Karišić. ISBN 978-86-85345-00-5.

- Sreten Petković (1 January 1999). Chilandar. Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-80879-19-2.

- Радић, Радмила (1998). Хиландар у државној политици Краљевине Србије и Југославије 1896-1970. Београд: Службени лист СРЈ. ISBN 9788635504018.

- Subotić, Gojko, ed. (1998). Hilandar Monastery. The Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences. ISBN 86-7025-276-7.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić. ISBN 9788644102717.

- Živković, Tibor; Bojanin, Stanoje; Petrović, Vladeta, eds. (2000). Selected Charters of Serbian Rulers (XII-XV Century): Relating to the Territory of Kosovo and Metohia. Athens: Center for Studies of Byzantine Civilisation.

- Živojinović, M. (1998) Vlastelinstvo manastira Hilandara u srednjem veku. u: Subotić G. (ur.) Manastir Hilandar, Beograd: SANU - Galerija

Further reading

- Fotić, Aleksandar (1994). "Lʹ Eglise chrétienne dans lʹEmpire ottoman: Le monastére Chilandar à lʹépoque de Sélim II". Dialogue: Revue trimestrielle d'arts et de sciences. 12 (3): 53–64.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (1999). "Dispute Between Chilandar and Vatopedi over the Boundaries in Komitissa (1500)". 'Αθωνικὰ Σύμμεικτα: Athonika Symmeikta. 7: 97–107.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2000). "Despina Mara Branković and Chilandar: Between the Desired and the Possible". Осам векова Хиландара: Историја, духовни живот, књижевност, уметност и архитектура. Београд: САНУ. pp. 93–100.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2003). "The Collection of Ottoman Documents in the Monastery of Hilandar (Mount Athos)". Balkanlar ve Italya'da Sehir ve Manastir Arsivlerindeki Turkce Belgeler Semineri. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 31–37.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2005). "Non-Ottoman Documents in the Kâdîs' Courts (Môloviya, Medieval charters): Examples from the Archive of the Hilandar Monastery (15th-18th C.)". Frontiers of Ottoman Studies: State, Province, and the West. Vol. 2. London: Tauris. pp. 63–73.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2007). "The Metochion of the Chilandar Monastery in Salonica (Sixteenth-Seventeenth Centuries)". The Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, the Greek Lands: Toward a Social and Economic History. Istanbul: The Isis Press. pp. 109–114.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Xenophontos in the Ottoman Documents of Chilandar (16th-17th C.)". Хиландарски зборник. 12: 197–213.

External links

- Official website (in Serbian)

- Hilandar monastery at the Mount Athos website

- Another page dedicated to Hilandar Monastery Archived 2011-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos from Hilandar

- Towards Former Beauty[permanent dead link] Information on the recent fire and reconstruction work (in English)

- Hilandar Research Library Ohio State University Collection—the largest collection of medieval Slavic manuscripts on microform in the world

- Monastery Chilandar, O manastiru Hilandar (in Serbian)