Sarepta

| |

| Location | Lebanon |

|---|---|

| Region | South Governorate |

| Coordinates | 33°27′27″N 35°17′45″E / 33.45750°N 35.29583°E |

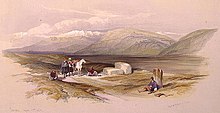

Sarepta (near modern

Most of the objects by which Phoenician culture is characterised are those that have been recovered scattered among Phoenician colonies and trading posts; such carefully excavated colonial sites are in Spain, Sicily, Sardinia and Tunisia. The sites of many Phoenician cities, like Sidon and Tyre, by contrast, are still occupied, unavailable to archaeology except in highly restricted chance sites, usually much disturbed. Sarepta[1] is the exception, the one Phoenician city in the heartland of the culture that has been unearthed and thoroughly studied.

History

Sarepta is mentioned for the first time in the voyage of an Egyptian in the 14th century BCE.[2] Obadiah says it was the northern boundary of Canaan: “And the exiles of this host of the sons of Israel who are among the Canaanites as far as Zarephath (Heb. צרפת), and the exiles of Jerusalem who are in Sepharad, will possess the cities of the south.”[3] The medieval lexicographer, David ben Abraham Al-Alfāsī, identifies Zarephath with the city of Ṣarfend (Judeo-Arabic: צרפנדה).[4] Originally Sidonian, the town passed to the Tyrians after the invasion of Shalmaneser IV, 722 BCE. It fell to Sennacherib in 701 BCE.

The first

Zarephath (צרפת ṣārĕfáṯ, tsarfát; Σάρεπτα, Sárepta) in Hebrew became the

Sarepta is the location of a Shia shrine to

After the Islamization of the area, in 1185, the

Ecclesiastical history

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Sarepta as a Christian city was mentioned in the

Titular sees

The diocese was nominally restored as

Sarepta of the Maronites

This

It has had the following incumbents of the fitting episcopal (lowest) rank:

- Emile Eid (1982.12.20 – death 2009.11.30), in the Promoter of Justiceof the same Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura (1969 – 1980)

- Hanna G. Alwan, Tribunal of the Roman Rota(1996.03.04 – 2011.08.13).

Sarepta of the Romans

It was established as titular bishopric no later than the 15th century. It has been vacant for decades, having had the following incumbents:

- Theodorich, (around 1350), as Roman Catholic Diocese of Olomouc (Moravia)

- Jaroslav of Bezmíře, appointed Bishop of Sarepta on 1394.7.15 by Pope Boniface IX[13]

- Guillaume Vasseur, Dominican Order (O.P.) (1448.10.23 – death 1476?), no actual prelature

- Gilles Barbier, Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Tournai (Belgium) (1476.04.03 – 1494.03.28)

- Nicolas Bureau, O.F.M. (1519.12.02 – death 1551) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Tournai (Belgium) (1519.12.02 – 1551)

- Guillaume Hanwere (1552.04.27 – 1560) as Auxiliary Bishop of above Tournai (Belgium) (1552.04.27 – 1560)

- Johannes Kaspar Stredele 'Austrian) (1631.12.15 – death 1642.12.28) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Passau (Bavaria, Germany) (1631.12.15 – 1642.12.28)

- Wojciech Ignacy Bardziński (1709.01.28 – death 1722?) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Kujawy–Pomorze(Poland) (1709.01.28 – 1722?)

- Cardinal-Priestwith no Title assigned (1771.12.16 – 1777.10.27)

- Johann Anton Wallreuther (1731.03.05 – 1734.01.16) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Worms(Germany) (1731.03.05 – 1734.01.16)

- Jean de Cairol de Madaillan (1760.01.28 – 1770.01.29) as Auxiliary Bishop of Grenoble(France) (1771.12.16 [1772.01.23] – 1779.12.10)

- Jean-Denis de Vienne (1775.12.18 – death 1800) as Auxiliary Bishop of Lyon (France) (1775.12.18 – 1800)

- Alois Jozef Krakowski von Kolowrat (1800.12.22 – 1815.03.15) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Praha (Prague, Bohemia, now Czech Republic) (1831.02.28 – death 1833.03.28)

- Johann Heinrich Milz (1825.12.19 – death 1833.04.29) as Auxiliary Bishop of Trier (Germany) (1825.12.19 – 1833.04.29)

- Johann Stanislaus Kutowski (1836.02.01 – death 1848.12.29) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Chełmno (Kulm, Poland) (1836.02.01 – 1848.12.29)

- Franz Xaver Zenner (1851.02.17 – death 1861.10.29) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Wien(Vienna, Austria) (1851.02.17 – 1861.10.29)

- Nicholas Power (1865.04.30 – death 1871.04.05) as Coadjutor Bishop of Killaloe(Ireland) (1865.04.30 – 1871.04.05)

- Jean-François Jamot (1874.02.03 – 1882.07.11) as only Northern Canada (Canada) (1874.02.03 – 1882.07.11); next (see) promoted first Bishop of Peterborough(Canada) (1882.07.11 – death 1886.05.04)

- Antonio Scotti (1882.09.25 – 1886.01.15) as Auxiliary Bishop of Alife (Italy) (1886.01.15 – retired 1898.03.24), emeritate as Titular Bishop of Tiberiopolis(1898.03.24 – death 1919.06.10)

- Paulus Palásthy (1886.05.04 – death 1899.09.24) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Esztergom (Hungary) (1886.05.04 – 1899.09.24)

- Filippo Genovese (Italian) (1900.12.17 – death 1902.12.16), no actual prelature

- Joseph Müller (1903.04.30 – death 1921.03.21) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Köln(Cologne, Germany) (1903.04.30 – 1921.03.21)

- Edward Doorly (1923.04.05 – 1926.07.17) as Coadjutor Bishop of Elphin (Ireland) (1923.04.05 – succession 1926.07.17); next Bishop of Elphin (1926.07.17 – 1950.04.05)

- Petar Dujam Munzani (1926.08.13 – 1933.03.16) as Apostolic Administrator of Archdiocese of Zadar (Croatia) (1926.08.13 – succession 1933.03.16); later Archbishop of Zadar (Croatia) (1933.03.16 – retired 1948.12.11), emeritate as Titular Archbishop of Tyana(1948.12.11 – death 1951.01.28)

- François-Louis Auvity (1933.06.02 – 1937.08.14) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Bourges (France) (1933.06.02 – 1937.08.14); later Bishop of Mende (France) (1937.08.14 – retired 1945.09.11), emeritate as Titular Bishop of Dionysiana (1945.09.11 – death 1964.02.15)

- Francesco Canessa (1937.09.04 – 1948.01.14)

- John Francis Dearden(later Cardinal) (1948.03.13 – 1950.12.22)

- Athanasios Cheriyan Polachirakal (1953.12.31 – 1955.01.27)

- Luis Andrade Valderrama, Friars Minor(O.F.M.) (1955.03.09 – 1977.06.29)

Archaeology

A

The low tell on the seashore was excavated by James B. Pritchard over five years from 1969 to 1974. [15] [16] Civil war in Lebanon put an end to the excavations.

The site of the ancient town is marked by the

Pritchard's excavations revealed many artifacts of daily life in the ancient Phoenician city of Sarepta: pottery workshops and

The climax of the Sarepta discoveries at Sarafand is the cult shrine of "Tanit/Astart", who is identified in the site by an inscribed votive ivory plaque, the first identification of Tanit in her homeland. The site revealed figurines, further carved ivories, amulets and a cultic mask.[17]

Other uses of the name

In

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- List of Catholic dioceses in Lebanon

References

- ^ Identification of the site is secured by inscriptions that include a stamp-seal with the name of Sarepta.

- Chabas, Voyage d'un Egyptien, 1866, pp 20, 161, 163

- ^ Obadiah 1:20

- ^ The Hebrew-Arabic Dictionary known as "Kitāb Jāmi' Al-Alfāẓ (Agron)," p. xxxviii, pub. by Solomon L. Skoss, 1936 Yale University

- ^ Luke 4:26

- ^ Designated Area I, it was excavated in 1969-70.

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews, Book VIII, 13:2

- Natural History, Book V, 17

- ISBN 9780857736208– via books.google.com.

- ^ Monachus Borchardus, Descriptio Terrae sanctae, et regionum finitarum, vol. 2, pp. 9, 1593

- ^ Piotr Górecki, Parishes, Tithes and Society in Earlier Medieval Poland c. 1100-c. 1250, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. i-ix+1-146, 1993

- ^ Geyer, Intinera hierosolymitana, Vienna, 1898, 18, 147, 150

- ^ "Inkvizitoři v Českých zemích v době předhusitské" (PDF). p. 63. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, pp. 95 & 135. Imprimerie Catholique. Archived from the original on 24 December 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ISBN 0-934718-24-5

- ISBN 0-8170-0487-4

- ^ Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia. “Two Phoenician Inscriptions Carved in Ivory: Again the Ur Box and the Sarepta Plaque.” Orientalia 59, no. 1 (1990): 58–66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43075770.

- OCLC 15252529. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

Sources

- Pritchard, James B. Recovering Sarepta, a Phoenician City: Excavations at Sarafund, 1969-1974, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania (Princeton: Princeton University Press) 1978, ISBN 0-691-09378-4

- William P. Anderson, Sarepta I: The late bronze and Iron Age strata of area II.Y : the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania excavations at Sarafand, Lebanon (Publications de l'Universite libanaise), Département des publications de l'Universite Libanaise, 1988

- Issam A. Khalifeh, Sarepta II: The Late Bronze and Iron Age Periods of Area Ii.X, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1988, ISBN 99943-751-5-6

- Robert Koehl, Sarepta III: the Imported Bronze & Iron Age, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1985, ISBN 99943-751-7-2

- James B. Pritchard, Sarepta IV: The Objects from Area Ii.X, University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, 1988, ISBN 99943-751-9-9

- Lloyd W. Daly, A Greek-Syllabic Cypriot Inscription from Sarafand, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 40, pp. 223–225, 1980

- Dimitri Baramki, A Late Bronze Age tomb at Sarafend, ancient Sarepta, Berytus, vol. 12, pp. 129–42, 1959

- Charles Cutler Torrey, The Exiled God of Sarepta, Berytus, vol. 9, pp. 45–49, 1949