Serbs in Vojvodina

Srem 238,200 (84.31%) | | |

| Languages | ||

|---|---|---|

| Serbian | ||

| Religion | ||

| Serbian Orthodox Church | ||

| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

The Serbs of Vojvodina are the largest ethnic group in this northern province of Serbia. For centuries, Vojvodina was ruled by several European powers, but Vojvodina Serbs never assimilated into cultures of those countries. Thus, they have consistently been a recognized indigenous ethnic minority with its own culture, language and religion. According to the 2022 census, there were 1,190,785 Serbs in Vojvodina or 68.43% of the population of the province.

History

Early medieval period

Before the

During the Roman rule, the original inhabitants were heavily Romanized.The

In the 9th century the region of present-day Vojvodina was ruled by the two local Bulgaro-Slavic

Hungarian rule

Parts of Vojvodina were conquered by the

From 1282 to 1316 Serbian King

An increasing number of Serbs began settling in the Vojvodina region from the 14th century onward. By 1483, according to a Hungarian source, as much as half of the population of the Vojvodina territory of the Kingdom of Hungary at the time consisted of Serbs. The Hungarian kings encouraged the immigration of Serbs to the Kingdom, and hired many of them as soldiers and border guards. A letter of King Matthias from 12 January 1483 mentions that 200,000 Serbs had settled the Hungarian kingdom in the last four years.[4] Despot Vuk and his warriors were greatly rewarded with estates, also including places in Croatia. Also, by this time, the Jakšić family had become increasingly notable, and held estates stretching over several counties in the kingdom.[5] The territory of Vuk Grgurević (1471–85), the Serbian Despot in Hungarian service (as "Despot of the Kingdom of Rascia"), was called "Little Rascia".[6]

After the

A 1542 document describes that "Serbia" stretched from Lipova and Timișoara to the Danube, while a 1543 document that Timișoara and Arad being located "in the middle of Rascian land" (in medio Rascianorum).[7] At that time, the majority language in the region between Mureș and Körös was indeed Serbian.[7] Apart from Serbian being the main language of the Banat population, there were 17 Serbian monasteries active in Banat at that time.[8] The territory of Banat had received a Serbian character and was called "Little Rascia".[9]

-

Slavs (including Serbs) in Vojvodina, 7th century

-

Realm of Stefan Dragutin, 13th-14th century, according to the book of historian Stanoje Stanojević

-

Serbian Empire ofJovan Nenad, 1526-1527

-

Duchy of Syrmia of Radoslav Čelnik in 1527-1530

-

Serbian Patriarchate of Peć (16th-17th century)

Ottoman rule

The

as its capital. At the pitch of his power, Jovan Nenad proclaimed himself "Serbian Emperor" in Subotica. Taking advantage of the extremely confused military and political situation, the Hungarian noblemen from the region joined forces against him and defeated the Serbian troops in the summer of 1527. "Emperor" Jovan Nenad was assassinated and his state collapsed.After the assassination of Jovan Nenad, the general commander of his army, Radoslav Čelnik, moved with part of the former emperor's army from Bačka to Srem, and acceded into the Ottoman service. Radoslav Čelnik then ruled over Srem as Ottoman vassal and took for himself the title of the duke of Srem, while his residence was in Slankamen.

The establishment of the Ottoman rule caused a massive depopulation of the Vojvodina region. Most of the Hungarians and many local Serbs fled from the region and escaped to the north. The majority of those who left in the region were Serbs, mainly now engaging either in farming either in Ottoman military service.

Under Ottoman policy, many Serbs were newly settled in the region. During the Ottoman rule, most of the inhabitants of the Vojvodina region were Serbs.[10] In that time, villages were mostly populated with Serbs, while cities were populated with Muslims and Serbs. In 1594 Serbs in Banat started a large uprising opposing Turkish rule.[12] This was one of three largest Serbian uprisings in history, and the largest one before the First Serbian Uprising led by Karađorđe.

-

Approximate territory that, according to various sources, was ethnographically named Rascia (Raška, Racszag,[13] Ráczország, Ratzenland, Rezenland) between 16th and 18th century

-

Great Serb migration, 1690

-

Serb settlements in Banat, 1743

Habsburg rule

The

During the

]During the Austrian rule many non-Serbs also settled in the territory of present-day Vojvodina. They were mainly (

,Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Vojvodina was a cultural centre of the Serb people. Especially important cultural centres were:

During the

The Hungarian government replied by the use of force: on June 12, 1848, a war between Serbs and Hungarians started. Austria took the side of Hungary at first, demanding from the Serbs to "go back to being obedient". Serbs were aided by volunteers from autonomous Ottoman Principality of Serbia. A consequence of this war, was the expansion of the conservative factions. Since the Austrian court turned against the Hungarians in the later stage of revolution, the feudal and clerical circles of Serbian Voivodship formed an alliance with Austria and became a tool of the Viennese government. Serbian troops from the Voivodship then joined the Habsburg army and helped in crushing the revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary.

After the defeat of the Hungarian revolution, by a decision of the Austrian

In 1860 the Voivodship of Serbia and Tamiš Banat was abolished and most of its territory (Banat and Bačka) was incorporated into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, although direct Hungarian rule began only in 1867, when the Kingdom of Hungary gained autonomy within the newly formed Austria-Hungary. Unlike Banat and Bačka, the Srem region was in 1860 incorporated into the Kingdom of Slavonia, another separate Habsburg crown land. However, the Kingdom of Slavonia was too incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary in 1868.

After the Voivodship was abolished, one Serb politician, Svetozar Miletić, appeared in the political sphere. He demanded national rights for Serbs and other non-Hungarian peoples of the Kingdom of Hungary, but he was arrested and imprisoned because of his political demands. In 1867, the Austrian Empire was transformed into Austria-Hungary, with the Kingdom of Hungary becoming one of two autonomous parts of the new state. This was followed by a policy of Hungarization of the non-Hungarian nationalities, most notably promotion of the Hungarian language and suppression of Slavic languages (including Serbian).[citation needed]

The

-

Vojvodina, 18th-19th century - Districts of Potisje and Velika Kikinda, Military Frontier sections in Banat, Bačka and Syrmia and Kingdom of Slavonia

-

Proclaimed borders of the Serbian Voivodship, 1848

-

Frontlines in Vojvodina in 1848-1849

-

Voivodship of Serbia and Tamiš Banat and Principality of Serbia, 1849

Yugoslavia and Serbia

- See also: SAP Vojvodina

At the end of

The difficult time period for the Serbs in Vojvodina was a

The Axis occupation ended in 1944 and the autonomous province of Vojvodina (incorporating Srem, Banat and Bačka) was formed within Yugoslavia in 1945 as a part of Serbia. The province was created as a territorial autonomy for all peoples who live in it, with the significant role of the Serbs, who were ethnic majority in the province.

-

Unification of Vojvodina with Serbia, 1918

-

Occupation of Vojvodina, 1941-1944

-

Vojvodina within Socialist Republic of Serbia, 1945-1989

Demographics

| Year | Serbs | Percentage | Total Population of Vojvodina |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 510,186 | 33.8% | 1,512,983 |

| 1921 | 526,134 | 34.7% | 1,528,238 |

| 1931 | 528,000 | 33.0% | 1,624,158 |

| 1941 | 577,067 | 35.3% | 1,636,367 |

| 1948 | 841,246 | 50.6% | 1,663,212 |

| 1953 | 865,538 | 50.9% | 1,699,545 |

| 1961 | 1,017,713 | 54.9% | 1,854,965 |

| 1971 | 1,089,132 | 55.8% | 1,952,535 |

| 1981 | 1,107,735 | 54.4% | 2,034,772 |

| 1991 | 1,151,353 | 57.2% | 2,012,517 |

| 2002 | 1,321,807 | 65.0% | 2,031,992 |

| 2011 | 1,289,635 | 66.7% | 1,931,809 |

| 2022 | 1,190,785 | 68.4% | 1,740,230 |

-

Serbs in Vojvodina according to the 2011 census

-

Percentage of Serbs in municipalities of Vojvodina according to the 2011 census

Culture

- in 1864.

- Serbian National Theatre, the oldest professional theatre among Serbs and South Slavs. It was founded in 1861 in Novi Sad.

- Normal School in Sombor, the oldest Serb normal school and the oldest normal school in this part of Europe, founded in 1778.

- Sremski Karlovci Gymnasium, the oldest Serb gymnasium. It was founded in 1791 in Sremski Karlovci.

- Kiev). It was founded in 1794 in Sremski Karlovci.

- The first Serb elementary school was founded in Bečej in 1703.

- The first modern Serb printing-house was founded in Kikinda in 1878.

- The first Serb library was opened in Kikinda in 1879.

- The first Serb bookshop was opened in Novi Sad in 1790.

- The first Serb church singing society was founded in Pančevo in 1838.

Serb monasteries in Srem

There are as many as eighteen

- Beočin – The time of founding is unknown. It is first mentioned in Turkish records dated in 1566/1567.

- Bešenovo – According to the legend, the monastery of Bešenovo was founded by Serbian king Dragutin at the end of the 13th century. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1545.

- Velika Remeta – Traditionally, its founding is linked to the king Dragutin. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1562.

- Vrdnik-Ravanica – The exact time of its founding is unknown. The records indicate that the church was built during the time of Metropolitan Serafim, in the second half of the 16th century.

- Grgeteg – According to tradition the monastery was founded by Zmaj Ognjeni Vuk (despot Vuk Grgurević), in 1471. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1545/1546.

- Divša – It is believed to have been founded by despot Jovan Branković in the late 15th century. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in the second half of the 16th century.

- Jazak – The monastery was founded in 1736.

- Krušedol – The monastery was founded between 1509 and 1516, by bishop Maksim (despot Đorđe Branković) and his mother Angelina.

- Kuveždin – Traditionally, its foundation is ascribed to Stefan Štiljanović. The first reliable records of it are dated in 1566/1569.

- Mala Remeta – The foundation is traditionally ascribed to the Serbian king Dragutin. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in the middle of the 16th century.

- Brankovićfamily. The first reliable mention of monastery is dated in 1641.

- Privina Glava – According to the legends, Privina Glava was founded by a man named Priva, in the 12th century. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1566/1567.

- Petkovica – According to the tradition, founded by the widow of Stefan Štiljanović, despotess Jelena. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1566/1567.

- Rakovac – According to a legend written in 1704, Rakovac is the heritage of a certain man, Raka, courtier of despot Jovan Branković. The legend states that Raka erected the monastery in 1498. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1545/1546.

- Staro Hopovo – According to the tradition, the monastery was founded by bishop Maksim (despot Đorđe Branković). The reliable data about the monastery date back to 1545/1546.

- Šišatovac – The foundation of the Monastery is ascribed to the refugee monks from the Serbian monastery of Žiča. The reliable facts illustrating the life of the monastery date back from the mid 16th century.

- Fenek – According to tradition, the founders of Monastery were Stefan and Angelina Branković, in the second half of the 15th century. The earliest historical records about the Monastery are dated in 1563.

- Zemun monastery in Zemunmunicipality. It was founded in 1786.

Serb monasteries in Bačka

- Kovilj monastery in Novi Sad municipality. The monastery was reconstructed in 1705–1707. According to the legend, the monastery of Kovilj was founded by the first Serb archbishop Saint Sava in the 13th century.

- Bođani monastery in Bač municipality. It was founded in 1478.

- Sombor monastery in Sombor municipality. It was founded in 1928–1933.

- In the outset of the 18th century there was a Serb monastery in Bački Monoštor near Sombor.

Serb monasteries in Banat

- Mesić monastery in Vršac municipality. It was founded in the 15th century.

- Vojlovica monastery in Pančevo municipality. It was founded during the time of despot Stefan Lazarević (1374–1427).

- Holy Trinity monastery in Kikinda. It was built in 1885–87 as a foundation of Melanija Nikolić-Gajčić.

- Saint Melanija monastery in Zrenjanin. It was founded in 1935 by Banatian bishop dr. Georgije Letić.

- Bavanište monastery in Kovinmunicipality. It was founded in the 15th century and was destroyed in 1716. It was rebuilt in 1858.

- Središte monastery in Vršac municipality. It was founded by despot Jovan Branković in the end of the 15th century.[14]

- Hajdučica monastery in Plandištemunicipality. It was founded in 1939.

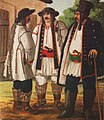

Images

-

Serb clothes in Bačka, 19th century

-

The dances from Syrmia

-

Serb national costume in Izbište, Banat

-

Kovilj Orthodox monasteryfrom the 13th century in Bačka

-

Grgeteg Orthodox monasteryfrom the 15th century in Syrmia

-

Velika Remeta Orthodox monastery

-

Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Nicholas in Vršac, Banat

Notable people

Medieval period

- .

- Vuk Grgurević (Zmaj Ognjeni Vuk), Serbian despot (1471–1485).

- Đorđe Branković, Serbian despot (1486–1496).

- Jovan Branković, Serbian despot (1496–1502).

- Srem from 1526 to 1527. He was born in town Lipovain northern Banat (today in Romania).

- Radič Božić, Serbian despot (1527–1528).

- Srem(1527–1530).

- Pavle Bakić, Serbian despot (1537).

- Stefan Štiljanović, Serbian despot (1537–1540).

Modern period

Politics and military:

- Jovan Monasterlija, vice-duke of Serbs (1691–1706).

- Sava Tekelija (1761–1842), politician and public worker. He was born in Arad.

- Josif Rajačić (1785–1861), the metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci, Serbian patriarch and administrator of Serbian Vojvodina.

- Stevan Šupljikac (1786–1848), the first duke of Serbian Vojvodina.

- Jovan Damjanić (Hungarian: János Damjanich, 1804–1849), a Hungarian general of Serbian origin.

- Jovan Subotić (1817–1886), politician and literate. He was born in village Dobrinci near Ruma.

- Svetozar Miletić (1826–1901), advocate, politician, mayor of Novi Sad, the political leader of Serbs in Vojvodina. He was born in the village Mošorin in Šajkaška.

- Jaša Tomić (1856–1922), publicist and politician. He lived in Novi Sad.

- Slobodan Jovanović (1869–1958), a prime minister of the Yugoslav government in exile during World War II, jurist and historian. He was born in Novi Sad.

- Dimitrije Stojaković (Hungarian: Döme Sztójay, 1883–1946), a Hungarian soldier and diplomat of Serbian origin, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary during World War II.

Culture, science and sports:

- Miroslav Antić (1932–1986), a Serbian poet. He was born in village Mokrin near Kikinda.

- Kula and he lived in Novi Sad.

- Đorđe Balašević, a prominent Serbian songwriter and singer. He was born in 1953 in Novi Sad.

- Jovan Đorđević (1826–1900), theatrical and public worker. He lived in Novi Sad.

- Jakov Jaša Ignjatović (1822–1889), a literate. He lived in Novi Sad.

- Đura Jakšić (1831–1878), a Serb poet, painter, narrator, play writer, bohemian, and patriot. He was born in Srpska Crnja.

- Jovan Jovanović Zmaj (1833–1904), one of the best-known Serb poets. He was born in Novi Sad.

- Paja Jovanović (1859–1957), one of the greatest Serbian realist painters. He was born in Vršac.

- Uroš Knežević (1811–1876), a Serb painter who was crucial in establishing the foundation of art in Serbia. He was born in Sremski Karlovci.

- Milan Konjović (1898–1993), a Serb painter. He was born in Sombor.

- Laza Kostić (1841–1910), a Serb literate. He was born in village Kovilj near Novi Sad, and he lived in Novi Sad.

- Mileva Marić (1875–1948), a Serb mathematician, and Albert Einstein's first wife. She was born in Titel.

- Lukijan Mušicki (1777–1837), a poet. He was born in Temerin.

- Tihomir Novakov (1929–Present), a Serb physicist. He was born and grew up in Sombor.

- Dositej Obradović (1742–1811), a Serb author, writer and translator. He was born in the village Čakovo in Banat (today Ciacova, in Romania).

- Zaharija Orfelin (1726–1785), writer. He was born in Vukovar or Petrovaradin, and he lived and died in Novi Sad. In 1768, he started the oldest Yugoslav magazine: "Slaveno-serbski magazin".

- Baja and he lived in Novi Sad.

- Jovan Sterija Popović (1806–1856), a Serb literate, the first Serb comediographer, and a founder of the Serb drama. He was born in Vršac.

- Uroš Predić (1857–1953), a painter. He was born in village Orlovat in Zrenjanin municipality and he lived in Novi Sad.

- .

- Branko Radičević, one of the best Serb poets of 19th century romanticism. He was born in 1824 in Slavonski Brod (today in Croatia), but he spent most of his life in Sremski Karlovci.

- Jovan Rajić (1726–1801), writer and historian. He was born in Sremski Karlovci.

- NBA. He was born in 1972 in village Prigrevica near Apatin.

- .

- Isidora Sekulić (1877–1958), a literate. She was born in village Mošorin in Titel municipality.

- Stevan Sremac (1855–1906), writer. He was born in Senta.

- Stanoje Stanojević (1874–1937), Serbian historian, university professor, academic and a leader of many scientific and publishing enterprises. He was born in Novi Sad.

- municipality.

- Momčilo Tapavica (1872–1949), the first Serb that won an Olympic medal. Born in Nadalj near Srbobran.

- Aleksandar Tišma (1924–2003), a literate. He was born in village Horgoš near Kanjiža.

- Kosta Trifković (1843–1875), was a Serb writer, one of the best comediographs of the time. He was born in Novi Sad.

See also

- Serbs

- Vojvodina

- History of Vojvodina

- Demographic history of Vojvodina

- Declaratory Rescript of the Illyrian Nation

- Hungarians in Serbia

References

- ISBN 9780313323843.

- ^ R. Veselinović, Istorija Srpske pravoslavne crkve sa narodnom istorijom I, Beograd 1969., page 18

- ^ R. Grujić, Pravoslavna Srpska crkva, Kragujevac 1989., page 22

- ISBN 9780521095310.

- ^ Ivić 1914, pp. 5–17.

- ^ Sima Lukin Lazić (1894). Kratka povjesnica Srba: od postanja Srpstva do danas. Štamparija Karla Albrehta. p. 149.

- ^ a b Posebna izdanja. Vol. 4–8. Naučno delo. 1952. p. 32.

- ^ Rascia 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Mihailo Maletić; Ratko Božović (1989). Socijalistička Republika Srbija. Vol. 4. NIRO "Književne novine". p. 46.

- ^ ISBN 9789004250383.

- ISBN 9789739680028.

- ISBN 9788675830153.

- ^ "Rascia". Časopis o Srbima u Vojvodini (Journal of Serbs in Vojvodina). I (1). Vršac. May 1996.

- ^ "Православље - НОВИНЕ СРПСКЕ ПАТРИЈАРШИЈЕ". Archived from the original on 2011-02-10. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

Sources

- Gavrilović, Vladan (1995). Srbi u gradovima srema: 1790–1849; kulturno-politička zbivanja. Nevkoš i Istočnik.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1929). Istorija srba u Vojvodini. Novi Sad: Matice srpska.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1914). Историја Срба у Угарској: од пада Смедерева до сеобе под Чарнојевићем (1459–1690). Zagreb: Привредникова.

- Kostić, Lazo M. (1999). Srpska Vojvodina i njene manjine: demografsko-etnografska studija. Dobrica knjiga.

- Popović, Dušan J. (1957). Srbi u Vojvodini (1): Od najstarijih vremena do Karlovačkog mira 1699. Matica srpska.

- Popović, Dušan J. (1959). Srbi u Vojvodini (2): Od Karlovačkog mira 1699 do Temišvarskog sabora. Matica srpska.

- Popović, Dušan J. (1963). Srbi u Vojvodini (3): Od Temišvarskog sabora do Blagoveštenskog sabora 1861. Matica srpska.

- Trifunović, Stanko (1997). "Slovenska naselja V-VIII veka u Bačkoj i Banatu". Novi Sad: Muzej Vojvodine.

- Vlahović, Petar (1977). "Миграциони процеси и етничка структура Војводине". Гласник Етнографског музеја. 41. Archived from the original on 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Vojvođani o Vojvodini: povodom desetogodišnjice oslobođenja i ujedinjenja. Udruženje Vojvođana. 1928.

- Milan Tutorov, Mala Raška a u Banatu, Zrenjanin, 1991.

- Drago Njegovan, Prisajedinjenje Vojvodine Srbiji, Novi Sad, 2004.

- Radmilo Petrović, Vojvodina, Beograd, 2003.

- Dragomir Jankov, Vojvodina – propadanje jednog regiona, Novi Sad, 2004.

- Dejan Mikavica, Srpska Vojvodina u Habsburškoj Monarhiji 1690–1920, Novi Sad, 2005.

- Branislav Bukurov, Bačka, Banat i Srem, Novi Sad, 1978.

- Miodrag Milin, Vekovima zajedno, Temišvar, 1995.

Further reading

- Bosić, Mila (1990). "DOSELJAVANJE SRBA U VOJVODINU DO KRAJA XIX VEKA I NJIHOV OBIČAJNI ŽIVOT" (PDF). Etnološke Sveske. 11: 43–53.

![Approximate territory that, according to various sources, was ethnographically named Rascia (Raška, Racszag,[13] Ráczország, Ratzenland, Rezenland) between 16th and 18th century](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/05/Rascia_in_pannonia_16th_18th_century.png/120px-Rascia_in_pannonia_16th_18th_century.png)