Muslims (ethnic group)

Muslimani Муслимани | |

|---|---|

Flag used to represent various Muslim minorities in the former Yugoslavia | |

| Total population | |

| c. 51,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 13,011 (2022)[1] | |

| 12,101 (2013)[2] | |

| 10,467 (2002)[3] | |

| 10,162 (2023)[4] | |

| 3,902 (2021)[5] | |

| 1,187 (2021)[6] | |

| Languages | |

| Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian and Gora dialect | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other mainly Muslim South Slavs | |

Muslims (

After the breakup of Yugoslavia, a majority of the Slavic Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the Bosniak ethnic designation, and they are today constitutionally recognized as one of three constituent nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Approximately 100,000 people across the rest of the former Yugoslavia consider themselves to be Slavic Muslims, mostly in Serbia. They are constitutionally recognized as a distinct ethnic minority in Montenegro.[8]

History

The Ottoman conquests led to many autochthonous inhabitants converting to Islam. However, nationalist ideologies appeared among South Slavs as early as the 19th century, as with the First and Second Serbian Uprising and the Illyrian movement, national identification was a foreign concept to the general population, which primarily identified itself by denomination and province.[9] The emergence of modern nation-states forced the ethnically and religiously diverse Ottoman Empire to modernise, resulting in several reforms. The most significant of these were the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and Imperial Reform Edict of 1856. These gave non-Muslim subjects of the Empire equal status and strengthened their autonomous Millet communities.[10]

There was a strong rivalry between South Slavic nationalisms.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina at that time, the population did not identify with national categories, except for a few intellectuals from urban areas who claimed to be Croats or Serbs. The population of Bosnia and Herzegovina primarily identified itself by religion, using the terms Turk (for Muslims), Hrišćani (Christians) or Greeks (for the Orthodox) and "Kršćani" or Latins (for the Catholics). Furthermore, the Bosna vilayet particularly resisted the reforms, which culminated with the

The revolt of the Bosnian ayans and the attempted formulation of provincial identity in the 1860s are often portrayed as the first signs of a Bosnian national identity. However, Bosnian national identity beyond confessional borders was rare, and the strong Bosnian identity of individual ayans or Franciscans expressed at that time was a reflection of regional affiliation, with a strong religious aspect. Christians identified more with the Croatian or Serbian nation. For Muslims, identity was more related to the defence of local privileges, but it did not call into question the allegiance to the Ottoman Empire. The use of the term "Bosniak" at that time did not have a national meaning, but a regional one. When Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, national identification was still a foreign concept to Bosnian Muslims.[12]

After World War II, in the

During the

Sometimes other terms, such as Muslim with capital M were used, that is, "musliman" was a practising Muslim while "Musliman" was a member of this nation (Serbo-Croatian uses capital letters for names of peoples but small for names of adherents).

The election law of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, recognizes the results from 1991 population census as results referring to Bosniaks.[20][21]

Population

- In Muslims (adherents of Islam) by their religious affiliation).[22]

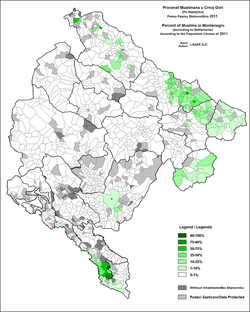

- In Montenegro census of 2011, 20,537 (3.3%) of the population declared as Muslims by nationality; while 53,605 (8.6%) declared as Bosniaks; while 175 (0.03%) Muslims by confession declared as Montenegrin Muslims.[23] Muslims and Bosniaks are considered as a two separate ethnic groups, and both of them have their own separate National Councils. Also, many Muslims consider themselves as Montenegrins of the Islamic faith. National Council of Muslims of Montenegro insists their mother tongue is Montenegrin.[24]

- In 2002 Slovenian Muslims. while 9,328 chose Muslims by nationality.[25]

- In Macedonian Muslims, separate of the 4,178 Torbeši, a minority religious group within the community of ethnic Macedonianswho are Muslims by religious affiliation. It is also important to note that most Torbeši were declared as Muslims by nationality before 1990.

- In Muslim Roma. The Bosniaks of Croatia are the largest minority practicing Islam in Croatia.[27][28][29][30]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "2022 Serbian census" (PDF).

- ^ "Popis 2013 BiH". popis.gov.ba. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ verska, jezikovna in narodna sestava (2002) od statistični urad republike Slovenije

- ^ "Stanovništvo Crne Gore prema nacionalnoj odnosno etničkoj pripadnosti, vjeri, maternjem jeziku i jeziku kojim se uobičajeno govori" (PDF). Monstat.org. 15 October 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Population by Ethnicity/Citizenship/Mother tongue/Religion" (xlsx). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "1. Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of North Macedonia, 2021 - first dataset" (PDF). State Statistical Office of North Macedonia. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Dimitrova 2001, pp. 94–108.

- ^ Đečević, Vuković-Ćalasan & Knežević 2017, pp. 137–157.

- ^ Bougarel 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Bougarel 2017, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bougarel 2017, p. 9.

- ^ a b Bougarel 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Banac 1988, pp. 287–288.

- ^ ISBN 9780300192582.

- ISBN 0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Sancaktar, Caner (1 April 2012). "Historical Construction and Development of Bosniak Nation". Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations. 11: 1–17. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ISBN 9789150619508.

- ISBN 9958-815-00-1

- ^ Fotini 2012, p. 189.

- ^ "Election law of Bosnia and Herzegovina" (PDF).

- ^ "CONSTITUTION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA" (PDF). The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- ^ 2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia

- ^ "MONTENEGRO STATISTICAL OFFICE, RELEASE, No: 83, 12 July 2011, Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011, p. 6" (PDF). Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Kurpejović 2018, pp. 48, 73, 102, 143–144.

- ^ "Population by religion and ethnic affiliation, Slovenia, 2002 Census". Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "1. Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of North Macedonia, 2021 - first dataset" (PDF). State Statistical Office of North Macedonia. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Population by ethnicity". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2001. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2002.

- ^ "10. Stanovništvo prema narodnosti - detaljna klasifikacija, po županijama". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2001. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2002.

- ^ "1. Population by ethnicity – detailed classification". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ "4. Population by ethnicity and religion". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

References

- ISBN 9781350003590.

- Fotini, Christia (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139851756.

Further reading

- ISBN 0801494931.

- Ćerić, Salim (1968). Muslimani srpskohrvatskog jezika. Sarajevo: Svjetlost.

- Dimitrova, Bohdana (2001). "Bosniak or Muslim? Dilemma of one Nation with two Names" (PDF). Southeast European Politics. 2 (2): 94–108.

- Đečević, Mehmed; Vuković-Ćalasan, Danijela; Knežević, Saša (2017). "Re-designation of Ethnic Muslims as Bosniaks in Montenegro: Local Specificities and Dynamics of This Process". East European Politics and Societies and Cultures. 31 (1): 137–157. S2CID 152238874.

- Donia, Robert J.; ISBN 9781850652120.

- Džaja, Srećko M. (2002). Die politische Realität des Jugoslawismus (1918-1991): Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Bosnien-Herzegowinas. München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 9783486566598.

- Džaja, Srećko M. (2004). Politička realnost jugoslavenstva (1918-1991): S posebnim osvrtom na Bosnu i Hercegovinu. Sarajevo-Zagreb: Svjetlo riječi. ISBN 9789958741357.

- Jović, Dejan (2013). "Identitet Bošnjaka/Muslimana". Politička Misao: Časopis za Politologiju. 50 (4): 132–159.

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2006). Slovenski muslimani zapadnog Balkana. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2008). Muslimani Crne Gore: Značajna istorijska saznanja, dokumenta, institucije, i događaji. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2011). Kulturni i nacionalni status i položaj Muslimana Crne Gore. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2014). Analiza nacionalne diskriminacije i asimilacije Muslimana Crne Gore. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore. ISBN 9789940620035.

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2018). Ko smo mi Muslimani Crne Gore (PDF). Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781603447249.