Diethylstilbestrol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | DES; Stilboestrol; Stilbestrol; (E)-11,12-Diethyl-4,13-stilbenediol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Metabolites | • (Z,Z)-Dienestrol[1] • Paroxypropione[1] • Glucuronides[2][3] |

| Elimination half-life | 24 hours[1][4] |

| Excretion | Urine, feces[2][3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), also known as stilbestrol or stilboestrol, is a

.DES is an

DES was discovered in 1938 and introduced for medical use in 1939.

The United States National Cancer Institute recommends[13] children born to mothers who took DES to undergo special medical exams on a regular basis to screen for complications as a result of the medication. Individuals who were exposed to DES during their mothers' pregnancies are commonly referred to as "DES daughters" and "DES sons".[10][14] Since the discovery of the toxic effects of DES, it has largely been discontinued and is now mostly no longer marketed.[10][15]

Medical uses

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

DES has been used in the past for the following indications:[5][additional citation(s) needed]

- Recurrent miscarriage in pregnancy

- symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal atrophy

- premature ovarian failure, and after oophorectomy)

- Gonorrheal vaginitis (discontinued following the introduction of the antibiotic penicillin)

- Prostate cancer and breast cancer

- Prevention of tall stature in tall adolescent girls

- Treatment of acne in girls and women

- As an emergency postcoital contraceptive

- As a means of chemical castration for treating hypersexuality and paraphilias and sex offenders[17][additional citation(s) needed]

- Prevention of the testosterone flare at the start of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH agonist) therapy[18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

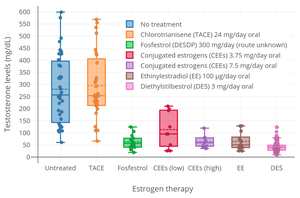

DES was used at a dosage of 0.2 to 0.5 mg/day in

Interest in the use of DES to treat prostate cancer continues today.

Oral DES at 0.25 to 0.5 mg/day is effective in the treatment of hot flashes in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer.[39]

Although DES was used to support pregnancy, it was later found not to be effective for this use and to actually be harmful.[40][41][42][43]

Side effects

At more than 1 mg/day, DES is associated with high rates of

Breast changes and feminization

The

In men treated with it for prostate cancer, DES has been found to produce high rates of gynecomastia (breast development) of 41 to 77%.[53]

Blood clots and cardiovascular issues

In studies of DES as a form of

Other long-term effects

DES has been linked to a variety of long-term adverse effects in women who were treated with it during pregnancy, and/or in their offspring, including increased risk of the following:[40]

- vaginal clear-cell adenocarcinoma

- vaginal adenosis

- T-shaped uterus

- uterine fibroids

- cervical weakness

- breast cancer

- infertility

- hypogonadism

- intersexual gestational defects

- depression

A comprehensive animal study in 1993 found a plethora of adverse effects from DES such as (but not limited to)

- genotoxicity (due to quinone metabolite)

- teratogenicity

- penile and testicular hypoplasia

- rhesus monkeys),

- papillary carcinoma (in canines), and

- malignant uterine mesothelioma (in squirrel monkeys).[55] Evidence was also found linking ADHD to F2 generations, demonstrating that there is at least some neurological and transgenerational effects in addition to the carcinogenic.[56]

Rodent studies reveal female reproductive tract cancers and abnormalities reaching to the

Overdose

DES has been assessed in the past in clinical studies at extremely high doses of as much as 1,500 to 5,000 mg/day.[36][59][60]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Estrogenic activity

DES is an

A dosage of 1 mg/day DES is approximately equivalent to a dosage of 50 µg/day ethinylestradiol in terms of systemic estrogenic potency.

DES has at least three

DES is a long-acting estrogen, with a nuclear retention of around 24 hours.[71][72]

| Estrogen | HF |

VE | UCa | FSH | LH | HDL-C | SHBG | CBG |

AGT |

Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Estrone | ? | ? | ? | 0.3 | 0.3 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Estriol | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ? | ? | ? | 0.67 |

| Estrone sulfate | ? | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5–0.7 | 1.4–1.5 | 0.56–1.7 |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.1–1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0–3.2 | 1.3–1.5 | 5.0 | 1.3–4.5 |

Equilin sulfate |

? | ? | 1.0 | ? | ? | 6.0 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 7.5 | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | 120 | 150 | 400 | 60–150 | 100 | 400 | 500–600 | 500–600 | 350 | 2.9–5.0 |

| Diethylstilbestrol | ? | ? | ? | 2.9–3.4 | ? | ? | 26–28 | 25–37 | 20 | 5.7–7.5 |

Sources and footnotes

Notes: Values are ratios, with estradiol as standard (i.e., 1.0). Abbreviations: HF = Clinical relief of liver proteins. Liver = Ratio of liver estrogenic effects to general/systemic estrogenic effects (hot flashes/gonadotropins ). Sources: See template. | ||||||||||

| Compound | Dosage for specific uses (mg usually)[a] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETD[b] | EPD[b] | MSD[b] | MSD[c] | OID[c] | TSD[c] | ||

| Estradiol (non-micronized) | 30 | ≥120–300 | 120 | 6 | - | - | |

| Estradiol (micronized) | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | >5 | >8 | |

| Estradiol valerate | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | - | >8 | |

| Estradiol benzoate | - | 60–140 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estriol | ≥20 | 120–150[d] | 28–126 | 1–6 | >5 | - | |

| Estriol succinate | - | 140–150[d] | 28–126 | 2–6 | - | - | |

| Estrone sulfate | 12 | 60 | 42 | 2 | - | - | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 5–12 | 60–80 | 8.4–25 | 0.625–1.25 | >3.75 | 7.5 | |

| Ethinylestradiol | 200 μg | 1–2 | 280 μg | 20–40 μg | 100 μg | 100 μg | |

| Mestranol | 300 μg | 1.5–3.0 | 300–600 μg | 25–30 μg | >80 μg | - | |

| Quinestrol | 300 μg | 2–4 | 500 μg | 25–50 μg | - | - | |

| Methylestradiol | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diethylstilbestrol | 2.5 | 20–30 | 11 | 0.5–2.0 | >5 | 3 | |

| DES dipropionate | - | 15–30 | - | - | - | - | |

| Dienestrol | 5 | 30–40 | 42 | 0.5–4.0 | - | - | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | 3–5 | 30–60 | - | - | - | - | |

| Hexestrol | - | 70–110 | - | - | - | - | |

| Chlorotrianisene | - | >100 | - | - | >48 | - | |

| Methallenestril | - | 400 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estrogen | Form | Major brand name(s) | EPD (14 days) | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethylstilbestrol (DES) | Oil solution | Metestrol | 20 mg | 1 mg ≈ 2–3 days; 3 mg ≈ 3 days | |

| Diethylstilbestrol dipropionate | Oil solution | Cyren B | 12.5–15 mg | 2.5 mg ≈ 5 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | ? | 5 mg | ? mg = 21–28 days | ||

| Dimestrol (DES dimethyl ether) | Oil solution | Depot-Cyren, Depot-Oestromon, Retalon Retard | 20–40 mg | ? | |

| Fosfestrol (DES diphosphate)a | Aqueous solution | Honvan | ? | <1 day | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | Aqueous suspension | Farmacyrol-Kristallsuspension | 50 mg | ? | |

| Hexestrol dipropionate | Oil solution | Hormoestrol, Retalon Oleosum | 25 mg | ? | |

| Hexestrol diphosphatea | Aqueous solution | Cytostesin, Pharmestrin, Retalon Aquosum | ? | Very short | |

| Note: All by intravenous injection . Sources: See template.

| |||||

Antigonadotropic effects

Due to its estrogenic activity, DES has

Other activities

In addition to the ERs, an

DES has been identified as an

Pharmacokinetics

DES is

The

The

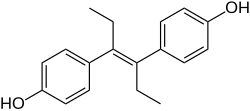

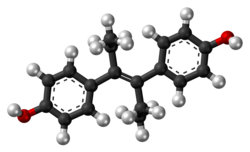

Chemistry

DES belongs to the

History

Synthesis

DES was first synthesized in early 1938 by Leon Golberg, then a graduate student of

DES research was funded by the UK Medical Research Council

Clinical use

DES was first marketed for medical use in 1939.

In 1941,

From the 1940s until the late 1980s, DES was FDA-approved as

In the 1940s, DES was used off-label to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with a history of miscarriage. On July 1, 1947, the FDA approved the use of DES for this indication. The first such approval was granted to

In the early 1950s, a

Despite an absence of evidence supporting the use of DES to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes, DES continued to be given to pregnant women through the 1960s. In 1971, a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a probable link between DES and vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma in girls and young women who had been exposed to this drug in utero. Later in the same year, the FDA sent an FDA Drug Bulletin to all U.S. physicians advising against the use of DES in pregnant women. The FDA also removed prevention of miscarriage as an indication for DES use and added pregnancy as a contraindication for DES use.[129] On February 5, 1975, the FDA ordered 25 mg and 100 mg tablets of DES withdrawn, effective February 18, 1975.[130] The number of persons exposed to DES during pregnancy or in utero during the period of 1940 to 1971 is unknown, but may be as high as 2 million in the United States. DES was also used in other countries, most notably France, the Netherlands, and Great Britain.

From the 1950s through the beginning of the 1970s, DES was prescribed to prepubescent girls to begin puberty and thus stop growth by closing growth plates in the bones. Despite its clear link to cancer, doctors continued to recommend the hormone for "excess height".[131]

In 1960, DES was found to be more effective than androgens in the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women.[132] DES was the hormonal treatment of choice for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women until 1977, when the FDA approved tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator with efficacy similar to DES but fewer side effects.[133]

Several sources from medical literature in the 1970s and 1980s indicate that DES was used as a component of

In 1973, in an attempt to restrict

In 1975, the FDA said it had not actually given (and never did give) approval to any manufacturer to market DES as a postcoital contraceptive, but would approve that indication for emergency situations such as rape or incest if a manufacturer provided patient labeling and special packaging as set out in a FDA final rule published in 1975.

In 1978, the FDA removed postpartum lactation suppression to prevent breast engorgement from their approved indications for DES and other estrogens.[141] In the 1990s, the only approved indications for DES were treatment of advanced prostate cancer and treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. The last remaining U.S. manufacturer of DES, Eli Lilly, stopped making and marketing it in 1997.[citation needed]

Trials

Diethylstilbestrol has been used countless times in studies on rats. Once it was discovered that DES was causing vaginal cancer, experiments began on both male and female rats.[142] Many of these male rats were injected with DES while other male rats were injected with olive oil, and they were considered the control group.[142] Each group received the same dosage on the same days, and the researchers performed light microscopy, electron microscopy, and confocal laser microscopy. With both the electron and confocal laser microscopy, it was prevalent that the Sertoli cells, which are somatic cells where spermatids develop in the testes, were formed 35 days later in the rats who were injected with Diethylstilbestrol compared to the rats in the control group.[142] Proceeding the completion of the trial, it was understood that rats of older age who were injected with DES experienced delay in sertoli cell maturation, underdeveloped epididymides, and drastic decrease in weight compared to its counterparts.[142]

The female rats used were inbred and most of them were given DES combined in their food. These rats were divided into three groups, one group who received no diethylstilbestrol, one group who had DES mixed into their diet, and the third group who had DES administered into their diet after day 13 of being pregnant.[143] Some rats who were given DES unfortunately died before delivering their pup.[143] The group that received DES in their food for 13 days while being pregnant resulted in early abortion and delivery failure.[143] These outcomes showed that DES had a detrimental effect on pregnancy when administered as often as it was. Providing the dosing of diethylstilbestrol later in the pregnancy term also made visible the occurrence of abortions among the rats.[143] Overall, any interaction with DES in female rats concluded in the rats' experiencing abortions, improper fetal growth, and the increase in sterility.[143]

A review of people who had been treated or exposed to DES was done to find out what long-term effects would show.[144] People for a long time had been treated during their pregnancy with DES, and there have been known to be toxic and adverse effects to the hormone therapy. "Exposure to DES has been associated with an increased risk for breast cancer in DES mothers (relative risk, <2.0) and with a lifetime risk of clear-cell cervicovaginal cancer in DES daughters of 1/1000 to 1/10 000."[144] Side effects of DES are proving to be long-term as it can cause increased risks of cancer after use.[144] There will be continued work to see how far the adverse effects of DES go after previous therapy and how it will affect offspring and the mothers longer-term.[144]

Regulations

In 1938, the ability to test the safety of DES on animals was first obtained by the FDA. The results from the preliminary tests showed that DES harmed the reproductive systems of animals. The application of these results to humans could not be determined, so the FDA could not act in a regulatory manner.[145]

New Drug Applications for DES approval were withdrawn in 1940 in a decision made by the FDA based on scientific uncertainty. However, this decision resulted in significant political pressure, so the FDA came to a compromise. The compromise meant that DES would be available only by prescription and would have to have warnings about its effects on the bottle, but the warning was dropped in 1945. In 1947, DES finally gained FDA approval for prescription to pregnant women who had diabetes as a method of preventing miscarriages. This led to the widespread prescription of DES to all pregnant women.[145]

In 1971, the FDA recommended against the prescription of DES to pregnant women.[146] As a result, DES then began to see a withdraw from the US market starting in 1972 and in the European market starting in 1978, but the FDA still did not withdraw its approval for the use of DES in humans.[147]

DES was classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. After classification as a carcinogen, DES had its FDA approval withdrawn in 2000.[146] DES is currently only in use for veterinary practices and in research trials as allowed by the FDA.[148]

Medical ethics

Lawsuits

In the 1970s, the negative publicity surrounding the discovery of DES's long-term effects resulted in a huge wave of lawsuits in the United States against its manufacturers. These culminated in a landmark 1980 decision of the

Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical company manufacturing DES, and the University of Chicago, had an action filed against them in regard to clinical trials from the 1950s. Three women filed the claim that their daughters had developments of abnormal cervical cellular formations as well as reproductive abnormalities in themselves and their sons.[151] The plaintiffs had asked the courts to certify their case as a class action but were declined by the courts. However, the courts issued an opinion that their case had merit. The court held that Eli Lilly had a duty to notify about the risks of DES once they became aware of them or should have become aware of them.[151] Under Illinois tort law, for the plaintiffs to recover under theories of breach of duty to warn and strict liability, the plaintiffs must have alleged injury to themselves. Ultimately, under their claims of breach of duty to warn and strict liability due to the plaintiffs citing risk of physical injury to others, not physical injury to themselves, the case was dismissed by the courts.[151] Although the case was not certified as class action and their claims of breach of duty to warn and strict liability was dismissed, the courts did not dismiss the battery allegations.[151] The issue was then to determine whether the University of Chicago had committed battery against these women but the case was settled before trial.[151] Part of the settlement agreement for this case, Mink v. University of Chicago, attorneys for the plaintiffs negotiated for the university to provide free medical exams for all offspring exposed to DES in utero during the 1950 experiments as well as treat the daughters of any women involved who develop DES-associated vaginal or cervical cancer.[151]

As of February 1991, there were over a thousand pending legal actions against DES manufacturers.[151] There are over 300 companies that manufactured DES according to the same formula and the largest barrier to recovery is determining which manufacturer supplied the drug in each particular case.[151] Many of the successful cases have relied on joint or several parties holding liability.

A lawsuit was filed in Boston Federal Court by 53 DES daughters who say their breast cancers were the result of DES being prescribed to their mothers while pregnant with them. Their cases survived a

The advocacy group DES Action USA helped provide information and support for DES-exposed persons engaged in lawsuits.[153]

Society and culture

At least on one occasion in New Zealand in the early 1960s, diethylstilbestrol was prescribed for the "treatment" of homosexuality.[155]

Veterinary use

Canine incontinence

DES has been very successful in treating female canine incontinence stemming from poor sphincter control. It is still available from compounding pharmacies, and at the low (1 mg) dose, does not have the carcinogenic properties that were so problematic in humans.[156] It is generally administered once a day for seven to ten days and then once every week as needed.[citation needed]

Livestock growth promotion

The greatest usage of DES was in the livestock industry, used to improve feed conversion in beef and poultry. During the 1960s, DES was used as a growth hormone in the beef and poultry industries. It was later found to cause cancer by 1971, but was not phased out until 1979.[157][158] Although DES was discovered to be harmful to humans, its veterinary use was not immediately halted. As of 2011, DES was still being used as a growth promoter in terrestrial livestock or fish in some parts of the world including China.[159]

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-397-51418-2.

Piperazine estrone sulfate and micronized estradiol were equipotent with respect to increases in SHBG, whereas [...] DES was 28.4-fold more potent [...]. With respect to decreased FSH, [...] DES was 3.8-fold, and ethinyl estradiol was 80 to 200-fold more potent than was piperazine estrone sulfate. The dose equivalents for ethinyl estradiol (50 µg) and DES (1 mg) reflect these relative potencies.220 [...] DES, a potent synthetic estrogen (Fig. 6-12), is absorbed well after an oral dosage. Patients given 1 mg of DES daily had plasma concentrations at 20 hours ranging from 0.9 to 1.9 ng per mL. The initial half-life of DES is 80 minutes, with a secondary half-life of 24 hours.223 The principal pathways of metabolism are conversion to the glucuronide and oxidation. The oxidative pathways include aromatic hydroxylation of the ethyl side chains and dehydrogenation to (Z,Z)-dienestrol, producing transient quinone-like intermediates that react with cellular macromolecules and cause genetic damage in eukaryotic cells.223 Metabolic activation of DES may explain its well-established carcinogenic properties.224

- ^ ISSN 1423-0399.

- ^ S2CID 23078614.

- ^ PMID 7154205.

- ^ PMID 4276416.

- ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ S2CID 24616324.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-8602-7.

- ^ "Effects of Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a Trans-placental Carcinogen". dceg.cancer.gov. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ S2CID 12630813.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7735-2501-6.

- ^ "DES Update: For Consumers". United States Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ "Diethylstilbestrol (DES) and Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- Broadly.

- PMID 15063479.

- ISBN 978-0-323-15726-1.

- S2CID 74365268.

- PMID 16986003.

- S2CID 36964191.

- PMID 2973364.

- PMID 3920802.

- PMID 2969641.

- S2CID 21824595.

- PMID 10678560.

- OCLC 6866559.

- PMID 794803.

- ISBN 978-1-4612-5525-3.

- S2CID 4403709.

- ^ S2CID 34563641.

- S2CID 21407416.

- PMID 14532759.

- ^ PMID 15046698.

- PMID 11502463.

- ^ PMID 7500443.

- PMID 17239273.

- ^ PMID 27889048.

- PMID 1627392.

- ^ ISSN 0008-5472.

- PMID 31367069.

- ^ PMID 12918007.

- PMID 23392570.

From the early 1940's until 1970's, DES was given to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage, which is often proceeded by a decline in estrogen levels. It later became apparent that DES treatment was mostly ineffective in preventing miscarriage [66], but nevertheless physicians continued prescribing DES to pregnant women. A recent article summarizes the effects of maternal exposure to DES during pregnancy and its adverse effects on pregnancy and fetal development in women [67], and show that this exposure increased 2nd trimester miscarriage by 3.8 -fold.

- ISSN 2212-9529.

- S2CID 33869704.

Several decades ago, diethylstilbestrol (DES) was considered efficacious in improving pregnancy outcome. Later data did not support this, and the exposed mothers and offspring have suffered from a variety of problems attributed to the drug.

- PMID 13638626.

[Diethylstilbestrol] suffers from the serious drawback that in doses above 1 mg. a day it is likely to produce nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, headache, and bloating in a proportion of patients varyingly estimated from 15 to 50%.

- ^ PMID 13157878.

- ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- ISSN 0021-972X.

- ISSN 0021-972X.

- PMID 21433876.

- PMID 20270944.

- ISSN 0002-9378.

- S2CID 31370289.

- PMID 16321765.

- PMID 24932461.

- PMID 1445734.

- PMID 29799929.

- PMID 16723367.

- PMID 21458804.

- PMID 576887.

- PMID 13005120.

- ISBN 978-1-84816-958-6.

- ISBN 978-3-642-46856-8.

- PMID 9048584.

- ^ PMID 22294742.

- PMID 26023144.

- ^ ISSN 0021-972X.

[Diethylstilbestrol], differing distinctly in chemical structure from the previously known estrogens, has been shown to produce all the biologic effects attributed to them, such as suppression of the antuitary (2), inhibition of body growth (2), proliferation of the ductile system of the breast (3), suppression of engorgement incident to lactation (4), hyperemia, edema, and distention of the uterus (5), proliferation of the endometrium (6), vaginal cornification (7), and swelling of the sexual skin (8). It likewise presumably has the supposed carcinogenic propensities of the true estrogens (9).

- ^ ISSN 0365-5555.

After it was shown by Dodds, Goldberg, Lawson, and Robinson that stilboestrol (4.4' dioxy-α-β-diethylstilbene had the same effects as the natural oestrones on the vaginal mucosa of castrated female rats, a great number of works have appeared, which show that this substance, despite its very great chemical difference from the natural female sexual hormones has practically the same effect as these in all respects. The most important of these investigations have been made by Dodds, Lawson and Noble, by Noble, by Bishop, Boycott and Zuckermann, by Erik Guldberg, by Engelhardt, by Winterton and MacGregor, by Erik Jacobsen and most recently by Kreitmair and Sickman, by Buschbeck and Hausknecht, by Cobet, Ratschow and Stechner. The previous experiments have been made on hens, mice, rats, guineapigs, rabbits, monkeys, and human subjects.

- ISSN 0022-0302.

- ISSN 0013-7227.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3.

- ISBN 978-3-662-07635-4.

- PMID 6277697.

- PMID 2215269.

- PMID 559617.

- ISBN 978-3-642-75101-1.

- ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

- ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

- ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ISBN 978-3-11-150424-7.

- PMID 779393.

- ISSN 0001-6349.

- ISSN 0172-777X.

- ^ PMID 29603164.

- PMID 29756046.

- PMID 15432047.

- PMID 14902290.

- ISSN 0001-6349.

There is no doubt that the conversion of the endometrium with injections of both synthetic and native estrogenic hormone preparations succeeds, but the opinion whether native, orally administered preparations can produce a proliferation mucosa changes with different authors. PEDERSEN-BJERGAARD (1939) was able to show that 90% of the folliculin taken up in the blood of the vena portae is inactivated in the liver. Neither KAUFMANN (1933, 1935), RAUSCHER (1939, 1942) nor HERRNBERGER (1941) succeeded in bringing a castration endometrium into proliferation using large doses of orally administered preparations of estrone or estradiol. Other results are reported by NEUSTAEDTER (1939), LAUTERWEIN (1940) and FERIN (1941); they succeeded in converting an atrophic castration endometrium into an unambiguous proliferation mucosa with 120–300 oestradiol or with 380 oestrone.

- ISBN 978-3-642-57636-2.

- ^ Martinez-Manautou J, Rudel HW (1966). "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". In Robert Benjamin Greenblatt (ed.). Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. pp. 243–253.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

- PMID 13370006.

- ^ PMID 4359746.

- ^ PMID 4699685.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58112-412-5.

- ^ PMID 16406864.

- ISBN 9780397590100.

- ^ PMID 6436700.

- S2CID 44250508.

- ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

- PMID 2973529.

- PMID 8677581.

- PMID 5124437.

- PMID 15161930.

- ^ PMID 16515477.

- ISBN 978-0-471-70468-3.

- PMID 14926876.

- ISSN 1935-4657.

- PMID 7195405.

- ISBN 978-3-642-67265-1.

- PMID 15458790.

- PMID 19737574.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-417213-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-086600-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-0348-0664-0.

- S2CID 4078256.

- OCLC 1483899.

- ^ ISBN 0-399-31008-8.

- ISBN 978-0-300-13607-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7868-6853-7.

- S2CID 19786742.

- ^ "Prostate cancer yields to a drug". The New York Times: 29. 15 December 1943.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-5973-6.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-34023-3.

- ISBN 0-00-093447-X.

- PMID 13104505.

- ISBN 0-300-03192-0.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (1971). "Certain estrogens for oral or parenteral use. Drugs for human use; drug efficacy study implementation". Fed Regist. 36 (217): 21537–8.; 36 FR 21537

- ^ a b FDA (1975). "Certain estrogens for oral use. Notice of withdrawal of approval of new drug applications". Fed Regist. 40 (25): 5384.; 25 FR 5384

- ^ Zuger A (2009-07-27). "At What Height, Happiness? A Medical Tale". The New York Times.

- .

- PMID 7001242.

- PMID 6199525.

- PMID 946104.

- PMID 122396.

- PMID 5171004.

- ^ FDA (1975). "Diethylstilbestrol as posticoital oral contraceptive; patient labeling". Fed Regist. 40 (25): 5451–5.; 40 FR 5451

- ^ FDA (1975). "Estrogens for oral or parenteral use. Drugs for human use; drug efficacy study; amended notice". Fed Regist. 40 (39): 8242.; 39 FR 8242

- ISBN 0-8290-0705-9.

- ^ FDA (1978). "Estrogens for postpartum breast engorgement". Fed Regist. 43 (206): 49564–7.; 43 FR 49564

- ^ S2CID 14127534.

- ^ PMID 19887736.

- ^ S2CID 25131834.

- ^ JSTOR 25473193.

- ^ PMID 34639609.

- PMID 33266302.

- PMID 28069260.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-1-78634-047-4.

- ^ S2CID 31494934.

- ^ Lavoie D (9 January 2013). "DES Pregnancy Drug Lawsuit: Settlement Reached Between Melnick Sisters And Eli Lilly And Co". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 10 January 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Collection: DES Action USA records | Smith College Finding Aids". Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- ^ West-Taylor Z (24 September 2016). "The Alan Turing Law – a Formal Pardon for Unpardonable Homophobia". Affinity magazine. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ Kilgallon, Steve (22 January 2023). "How 'gay conversion' drugs ruined this man's life". Stuff. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Urinary Incontinence". Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- PMID 22464649.

- ^ Gandhi R, Snedeker S (2000-06-01). "Consumer Concerns About Hormones in Food" (PDF). Fact Sheet #37, June 2000. Program on Breast Cancer and Environmental Risk Factors, Cornell University. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- S2CID 4711788.

Further reading

- Johnston E (2017). "Poisoned subjects: life writing of DES daughters". S2CID 152010855.

External links

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) and Cancer National Cancer Institute

- DES Update from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DES Action USA national consumer organization providing comprehensive information for DES-exposed individuals

- DES Booklets from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (c. 1980)

- DES Follow-up Study Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine National Cancer Institute's longterm study of DES-exposed persons (including the DES-AD Project)

- University of Chicago DES Registry of patients with CCA (clear cell adenocarcinoma) of the vagina and/or cervix

- DES Diethylstilbestrol Provides resources and social media links for general DES awareness